interview

'When you mourn, everything is included'

Leendert Sonnevelt

Leendert Sonnevelt is an Amsterdam-based writer, curator and stylist whose work criss-crosses the offroads of music, fashion and (youth) culture.

interview

Sonic Séance

Curator, stylist and writer Leendert Sonnevelt interviews Brian d’Souza, who has made Genius Loci, the first commissioned artwork for The Couch. Sonnevelt and d’Souza discuss the development of the artwork, and what it reveals about the ‘spirit’ of Het HEM.

21

min read

Despite death being a given for all of us ephemeral beings, it remains one of the most incomprehensible concepts to face or fathom. Loss, and the all-engulfing throes of individual and collective mourning it flings at us, can often seem impossible to cope with or comprehend. Perhaps the closest the living get to understanding and accepting death and loss is in art.

In GHOST, an interdisciplinary performance project supported partly by Het HEM, the artist Asa Horvitz invites us to simply be with death and all its endless facets. Inspired by the loss of friends and relatives, in particular the passing of his father, Horvitz and a group of kindred artists create and perform songs based on an AI system that’s fed 151 books on death, loss and grief. Surrounded by an array of sounds, silences, words, thoughts, questions, clothes and objects—from colourful ceramics, shared food and comfy cushions to giant gongs, synths, grand piano and a very loud horn band—the artist carefully lays out a landscape where every individual can have their own experience, their own existential encounter.

When Horvitz started working on GHOST, he asked himself: ‘If the experience of sitting Shivah [the week-long ritual of mourning in traditional Judaism] is not about one person but about the feeling of the dead in general, condensed into 90 minutes, what does that feel like?’ GHOST is the answer to that question, yet Horvitz doesn’t answer any questions for us. Instead, he creates an open space for individual and communal thought; an ever-expansive living room where you can laugh and/or cry, associate and/or dissociate, be alone and/or be together, navigate the tunnel and look for the light at its end.

Following the premiere of GHOST in the basement of De School, and ahead of the work’s digital and interactive re-iteration on The Couch, Leendert Sonnevelt sat down with Horvitz for post-performance reflections and—whether we can truly make peace with it or not—more thoughts on death, the hand it deals us, and how we come to terms with it.

Leendert Sonnevelt: I have to admit: before experiencing GHOST in person, it felt quite abstract to me. Then I saw your performance at De School and now I have (too) many questions. First of all, where are you at right now in terms of work/life?

Asa Horvitz: My life has been fully devoted to GHOST since January, but we started this piece back in 2017/18 and worked on it in different periods. Right now, there are three main lines going on in my work. One is very music-driven and conceptual, which is what GHOST comes out of. Another one is working with a group of dancers that I’ve been working with for the last years, mostly based in The Netherlands (we worked together for Het HEM when the building was still open). The third stems from my performance practice and elements like you saw in the beginning of GHOST: the history of images, ideas, theory, et cetera. There’ll be a third part in the trilogy that GHOST is part of, coming from that place. The cycle of work has become much more hybrid than I initially expected.

Is GHOST your most hybrid work so far?

No… but how do I explain this? With each project, I just try to use the media that best address the problems and questions that grab me in some way. I don’t think of myself as an interdisciplinary artist. Still, in the past I’ve made pieces where there was a performance, a website, a record—things tend to take on different forms. The particular things I use just depend on what I need in that moment.

While seeing GHOST I wrote down: ‘researcher, director, conductor, composer, musician, vocalist, editor, choreographer’ but also ‘participant, listener, observer’.

I will say, I don’t usually perform to this degree and I think that’s a big difference compared to my other pieces. In this case, due to the personal nature of the work, I felt like I had to. GHOST has a layer that’s very personal and emotional, and it has a layer that’s very abstract and structural. To bring the personal and emotional into it, I needed to be present.

You welcome the GHOST audience with a personal introduction that touches on the death of your relatives and friends, the AI technology that’s used, thoughts from Judaism and literature… Do you consider this an introduction to the work or is it a part of the work?

[Laughs] Well, that’s the trick! It’s framed as an introduction but it’s the beginning of the piece, which allows people to absorb information without realising that this performative thing is already happening. It’s very non-linear, it’s poetic, it’s structured like a dream. We jump from historical references to stuff about AI to stuff about my family, and that jumping puts you in the “logic” of disconnected things coming right after each other. I hate introductions and explanations; usually they close the possible interpretations of a work. But we figured that we needed it to help people identify relationships and enter into the different layers that happen at the same time. It opens people’s associations and that’s very necessary.

When I saw the performance, the audience brought up two questions/comments for the AI system: ‘What would Asa’s father say right now?’ and ‘I haven’t experienced the loss of a loved one yet’. The first one is really about you, the second about the person in the audience—don’t you think that’s an interesting summary of the piece?

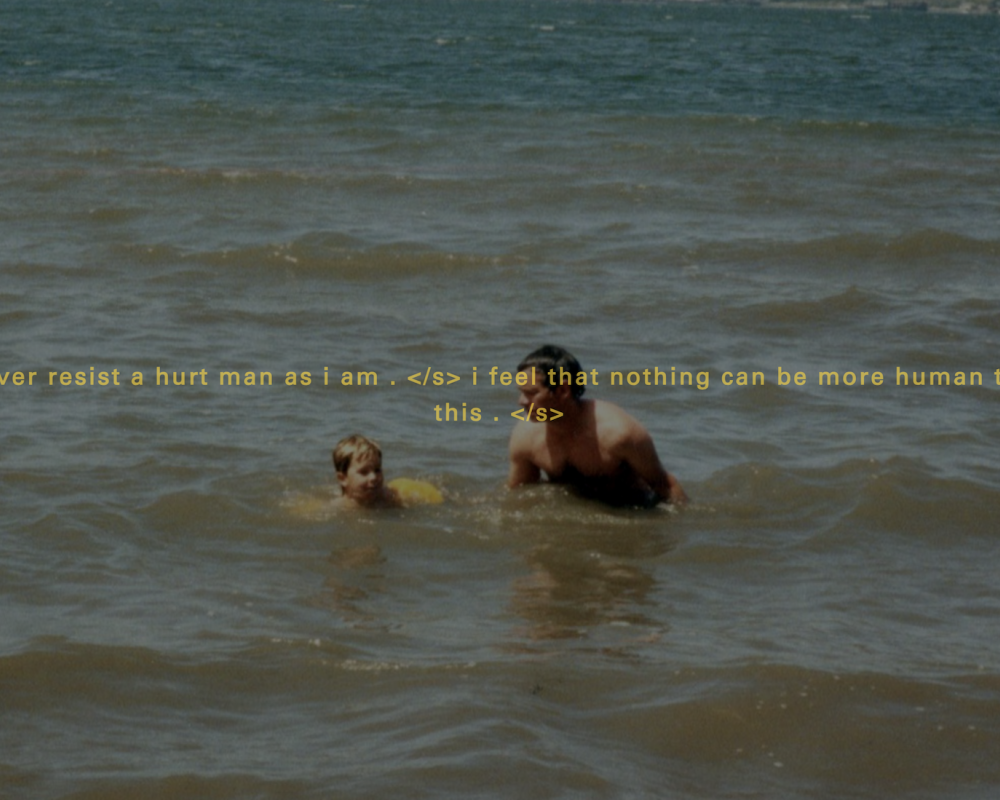

Yes. The whole impulse for this work, starting with the AI text and moving on to the music [whose lyrics are also generated by the AI], all came from the experience of having a lot of death in my life. In my early twenties the first guy I loved, who was also my best friend, died. I made a piece called VALES, which memorialised him. It was a strong experience and I’m glad that I did it, but when all these other people died I thought: ‘I really can’t do this again’. That hyper-personal aspect, with its images and details, felt impossible (I hate to say it – but I just didn’t have the capacity). I also had this feeling, with all this overwhelm, that I needed something more abstract. Something that’s driven by a real and personal story, the undeniable need to grieve, but also this desire for something more impersonal, open and structural. That tension is the aesthetic motor of the piece. In GHOST, there’s a meeting between the bodies of the performers and all this text, which is very abstract but full of images about death. It leaves a lot of room for interpretation, a zone where things are undecided.

When you were asked about your dad, I thought it was maybe a setup.

That was wild! [Laughs] I do know the person who asked, but it was not set up. I didn’t even know that she was coming. And the AI response was pretty amazing.

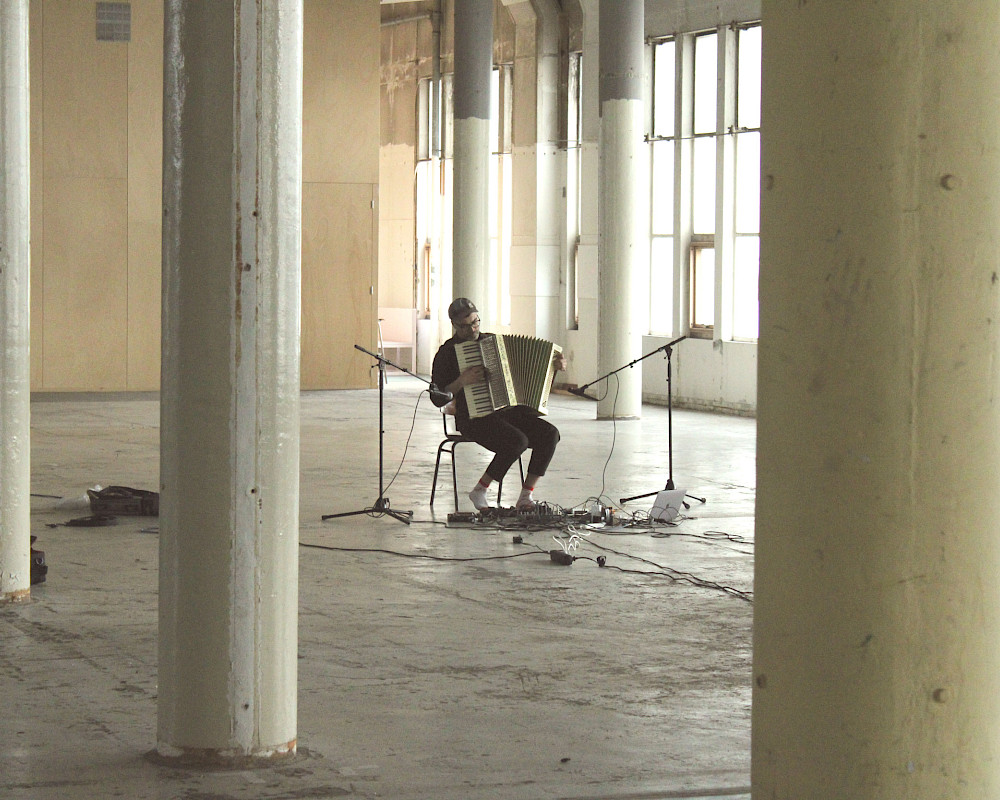

Right? Let’s go back to this tension you just touched on. At a certain point in the performance there is a piano solo which is quite abstract, but then it’s still your uncle—Wayne Horvitz, the brother of your father who passed away—playing the solo.

Exactly. Inviting my uncle was a crucial turning point. We did some versions where there was a trio without anybody else and then we brought in different musicians. The final decision to bring Wayne was based on this: even if his presence remains abstracted, the fact that he’s there holds this other dimension. Well, you already said it.

You mentioned that you have a weird relationship with artificial intelligence. Would you say that you use AI as a space for our own imagination/association to come alive?

What happened, to make it very concrete… My father had died and I was looking for some other way deal with loss and grief. I was very close with my father so there were a lot of intense feelings there. I was writing songs and music, abstracted stuff with a lot of repetition and fragmented lyrics. I felt like we were getting somewhere but it didn’t feel quite right. Then my friend, Seraphina Tarrant, sent me this text from an AI system that she’d built, and it was amazing and fragmented—it felt very right. From the very beginning we wanted to sing this text, but then the question came up: ‘Where is the text from?’ Well, it came from an AI system. ‘What is an AI system?’ It’s an archive of books or text that’s processed through an algorithm that you get inputs from. ‘Ok, so could we make our own?’ We were very lucky because Seraphina was building AI systems herself, she was working at a university and just wanted to play around with it. Only much later we started to realise the huge elephant we’d dragged with us, which is: everybody’s imagination and our own imagination about AI.

When we started to work past the level of text to make a performance, immediately all ideas were so bad and so cliché; like trying to turn the AI into a person. I realised: ‘fuck, there’s this whole imaginary world around this and how do we deal with it?’ Seraphina Goldfarb-Tarrant and Alejandro Calcaño really helped me find a position towards AI that made sense, one that was creative but also transparent. People tend to take AI and add their fantasy to it. I think we were lucky that, from the beginning, we were interested in the structure of this archive coming through and that becoming something new. We were not just interested in what you get from it. Somehow that’s very similar to trying to deal with the dead or the past. We had to spend a lot of time thinking about AI, going to conferences and nuancing this. It’s still a failure in the productive sense; in the performance we don’t accomplish anything with AI but turn it back on itself and use it to do something we already wanted to do otherwise.

As I was reading along and listening to the performance, I thought: it’s almost impossible not to look for a human voice in the words. So, how did you curate the text fragments?

Since we trained the AI system on a limited data set of 151 books, the voice is super consistent. Whatever you ask, it responds in the same kind of voice. We chose highlights but they aren’t that different from things we didn’t choose. There are some parts where I thought: ‘wow, that’s beautiful’. And in some lucky cases we got a whole song, verbatim. We were very practical; we mostly chose things we wanted to sing. Very early on, Carmen [Q. Rothwell] and I were singing and Ariadne [Randall] was processing, and we noticed that this text was pushing us to make music that doesn’t sound like other music we were making. That was very exciting and it was very instinctive. We found things that sit on this edge; you can almost project something onto it…

…but you cannot quite grasp it.

Exactly. It creates a situation in which people’s imagination is stirred but not exactly, totally. There’s enough room for your own associations to come up but there’s no clear narrative.

Maybe this is projection, but it reminds me of going to church as a child and not understanding a thing that was written in the King James Version of the Bible, yet always finding points of connection/association. Aside from that, church services were also way too long, making you zone out and travel into your own thoughts.

[Laughs] Yes, that experience of boredom is crucial. There’s enough time to start to sink down, to have your own associations, to disengage and reengage. I think it’s not a mistake that many charged symbolic gatherings organise time in this way. It gives you enough time to attach your own stuff. In the past few years I’d go to 45-minute performances and notice I’m totally engaged, but then I’d forget about it after. We were really looking for a mode of attention that’s a bit more difficult; it holds you at some moments and lets you go at other moments. I hope that it will resonate afterwards.

Speaking of the (time) structure of your performance: there’s a lot of repetition, there’s pieces that happen really fast compared to slow others, and then there’s moments where nothing happens at all. There’s time to breathe and at times it’s impossible to breathe. How did you create this structure?

Well, the short answer [laughs] is that there are three parts and an introduction. The first part is totally overwhelming and basically sticks your head under water: a ton of text, a ton of information, things are always happening for about 20-25 minutes. In the second part there is a more delineated song—song—song—song structure, which gives you more space. In the third part there’s even more space, that’s also when the horn band comes in. The main idea was trying to find a way for people to get productively disoriented. When you grieve someone it’s just too much, it’s overwhelming and it comes at you too hard! If the work was just that, it would keep people outside. So there’s the initial plunge and subsequently you find things you can attach to emotionally. At the same time, if it were structured in the opposite direction, it would probably also work; the structure is so musical, I think of it as a concert set where things could be modularly moved around. It’s also just intro—lots of stuff—horn band—end.

There are moments in the performance where you literally take a nap. Can you touch on the relationship between structure/time and grief?

Yes, there’s two aspects. We definitely thought about the Jewish practice of sitting Shivah, where you mourn for seven days after someone dies. During this time, you sit on low seats and you eat round food. We were thinking about what Oneka von Schrader, who worked with us on the choreography, named as the vibe of the “ceremonial living room” – casual and regal at the same time. If the experience of sitting Shivah for seven days is not about one person but about the feeling of the dead in general, condensed into 90 minutes, what would that feel like? We figured it actually needs to be very dense and ongoing. Also, like I said before, it’s this feeling of overwhelm and being lost, having some things to connect to but also feeling adrift. It’s an endlessness. When there’s more space later on in the piece, things land more because people are already too full, if that makes sense.

And then the horn band is the ultimate overwhelming factor?

Yes, and it has no text! That’s very important; basically, you can just resonate and don’t have to take in more language. At the end of the day, it’s not a representational piece. There’s enough visual stuff for people’s imagination to get stimulated, but we’re not playing people doing a thing. It happens on a one-to-one level.

Considering your subject matter, is GHOST still an emotionally intense/charged piece for you to perform?

It’s funny because I thought it wasn’t when we started working on it again, seven years after my dad died. Then I wrote the text that’s in the booklet and I totally fell apart. We were in Vienna for a work period and I was a wreck for four weeks, crying non-stop. I was very lucky because everyone was very supportive, especially Oneka who held certain moments when I couldn’t. It was a tough but ultimately good experience because there was a lot of unprocessed grief there. Now I feel good performing it, it feels fun, but I was not expecting that. We’ve been working on this material for a long time and all performers experienced losses in the process. It’s indeed a very intimate group of people and we all know each other’s stories.

In the GHOST booklet you describe a family in mourning: ‘Someone is annoyed, another person sad, another checks their phone for a work email, another is cranky, another goes out for bagels.’ I’m fascinated by these moments, where you switch between deep grief and super mundane things. In a way it’s similar to seeing performance art; one moment you think of the work email you forgot to send, the next you’re pondering existential questions.

Music does this to you! It creates a field of attention. Let’s say you go see a band. You’re immersed in an experience with other people but you’re also alone, you see the guy at the bar, you notice the pile of crap in the corner of the room… A friend of mine told me this: ‘when you mourn, everything is included’. I think that’s very true. When someone has died and you sit on the couch, the blanket on the couch becomes the saddest thing. You’re having a strong experience that attaches itself to all these different things. For that reason, the presence of mundane/basic things felt very important. It creates a space where a certain being with the dead, or a feeling of the dead, can happen.

If the experience of sitting Shivah for seven days is not about one person but about the feeling of the dead in general, condensed into 90 minutes, what would that feel like?

That’s also what I mean when I say ‘this is not about me’. You don’t have to accept my story, it’s just an example. It’s something that charged this work and opened a door, but you can give zero shits about my personal experience and hopefully still have a connection in some way. That’s important for me on a political level too; it points to a being together with people, an empathy with strangers, which is very different from this kind of mode of always having to sell your own experience. It’s not about my story being better than another person’s story—which is the mode a lot of society or the universe seems to operate in at the moment.

You mentioned that the mourning process includes or takes hold of everything. I feel that also includes the people who are still alive, somehow.

Can you say more about that? Sounds interesting.

Sure, it’s quite hard to put into words. To use your performance as an example, for me it triggered thoughts not only about the people I’ve lost through death or other ways, but also thought about the people I haven’t lost (yet).

Yeah, totally. The thing about GHOST is that the idea/feeling for the piece was always about making music with other people. It’s a performance but it’s a music piece (I guess there’s no name for that). Before I met Carmen, she actually came to my dad’s funeral in New York because Wayne invited her, most likely because he thought the music was going to be good. [Laughs] We didn’t know each other at all. She came and the music was great—we have very musical funerals because it’s a family of musicians—and there was this feeling of: this is for us. The presence of the dead person, that meaningfulness, charges the whole situation and it makes people play in an extraordinary way. Doing this thing, it’s really for the living. The reason for the horn band in GHOST is that we used to have very large groups of jazz musicians playing at our family funerals. That does something for the living that’s very important and feels really good too; it’s very sad but it’s very transformative, it moves something. Like Wayne’s text in the piece says: ‘you can imagine whatever you want about the dead, but so far they haven’t been playing music with us’. [Laughs]

Can you tell me more about the objects in the space?

Yes. Let’s start with the music again, which is very much influenced by medieval music and old forms of chanting and singing together. But also, 20th-century experimental music like Robert Ashley or Philip Glass and contemporary electronic music… whatever they call music people make now. [Laughs] The layers are very old and very new. We built that aesthetic using a lot of synthesisers, which we use very simply so things are very transparent and reflect the text from the AI system. This text is also very basic, very clear, and has these layers that feel old and new. As you said, it could be the King James Bible but also contemporary literature or theory. Mostly, we wanted the layers of the space to reflect that. There’s very old objects, things that feel ancient, as well as things that feel contemporary or digital.

The ceramics were done by a great Austrian ceramicist named Jacob Bartmann, inspired by a little ‘bird guy box’ modelled on 5000-year-old funeral boxes for bones found in Southeastern Europe and the Mediterranean. The rotating vase with holes was inspired by the Zohar, a 15th-century mystical Jewish text. It contains a long passage about the universe beginning with God smashing these vessels. It goes on to discuss how there’s certain things in the universe like God—and I extrapolated this to think about the dead—which cannot be contained or captured. It just goes everywhere. I saw this vase with holes in a museum and thought: ‘we have to make one’. Everyone thinks about the dead so differently; it’s still a mystery and no one knows. It’s always escaping. And then the gongs came from a dream that Ariadne had about cymbals, they kind of wash our singing away.

You performed GHOST in the basement of De School, a temporary nightclub in Amsterdam, which is quite a specific spot with a lot of history. I’m sure people, including myself, were thinking things like: ‘I made out with that person in that corner’.

Yes, that’s great! [Laughs] The first people to come in were a couple that immediately walked across the whole playing area to point out different spots. It was a risk that De School took, and it was very generous of them—they don’t usually show the club like this [with full lighting]. Before this, I also only knew the space as a seemingly infinite pool of darkness. I hope nobody took pictures.

Which parts of GHOST will be on The Couch?

What will be accessible is the (interactive) AI system, the music, some performance documentation and the text. There will probably be a large archive of recordings, too, including the music from the performance but also other music going back to 2018—we have almost four hours and there’s some great stuff that wasn’t in the performance. Also, we’re hoping to make a vinyl edition with Het HEM, containing a condensed version of the project.

Last question, but an important one. Why did you pick the title GHOST?

There’s a song called GHOST that I wrote before we got the AI text, which had this line in it: ‘Be a ghost, be a ghost, on the last flight out’. There’s this weird feeling when somebody dies where you both want them to stay and want them to go. Even if you love somebody, it’s a really funny process. You feel ‘I wish you were still here and I love you’ but you also feel ‘Get off me, get away from me, don’t haunt me, please go’. That double feeling was captured in the song, it stuck and we started to call the piece that. And then it was too late to change it. [Laughs]

And now it haunts you.

Exactly.