5

min read

"A good map will find its users. And people who are interested in maps, or simply need them, will find them"

In 2019, as part of Het HEM’s Chapter 2WO exhibition made with guest Nicolás Jaar, an international group of researchers, including artists, scientists and activists lived and worked in Het HEM’s building and on its terrain. Calling themselves Shock Forest Group after the Shock Forest or Plofbos, the forest on the Hembrug terrain that was planted to shield ammunition tests and military activity from the public eye, this group conducted an open, improvisational experiment in polyphony – the coexistence and harmony (or cacophony) of multiple voices and perspectives from humans to animals to environment and architecture. Cartographer, programmer and designer Bert Spaan was part of the first iteration of SFG, working on the visual archive that represents the cumulated research and connections SFG made throughout the residency.

We caught up with Bert four years after this iconic residency to ask him what he’s up to now – and how his time at Het HEM may have inspired him.

Het HEM: What was it like for you developing Shock Forest Group, and what was your role there?

Bert Spaan: I really valued (and still value) the opportunity to deeply get to know Het Hembrugterrein, its history, and to meet some of its former workers. I was not always able to participate in the group process in the way I hoped. This was because I only had 2 days a week to work on the project while some of the SFG group worked on it every day, and because the core of the group had quite a different way of working/thinking/talking than I was used to. But all in all, I wouldn’t have wanted to miss being part of SFG!

HH: What sort of research did you do (or what stayed with you) about the Hembrugterrein, Plofbos, and Het HEM’s building?

BS: I worked on the visual archive that we used to collect all research material, and I worked on collecting information about how the Hembrugterrein was connected to other parts of the Netherlands, Europe, and the rest of the world.

HH: Are you still in contact with anyone from SFG?

BS: Only with Jelger Kroese. [Jelger Kroese is a transdisciplinary researcher and designer and a current member of Shock Forest Group]

HH: Can you tell us about your current project, Allmaps? What are its implications?

BS: Allmaps is a continuation of my work for the New York Public Library. After returning from NYC in late 2017, I started working as a freelancer. Allmaps started as a tiny side project, and grew bigger over the years. Since last spring, I’m able to work on it full-time and sometimes hire other freelancers.

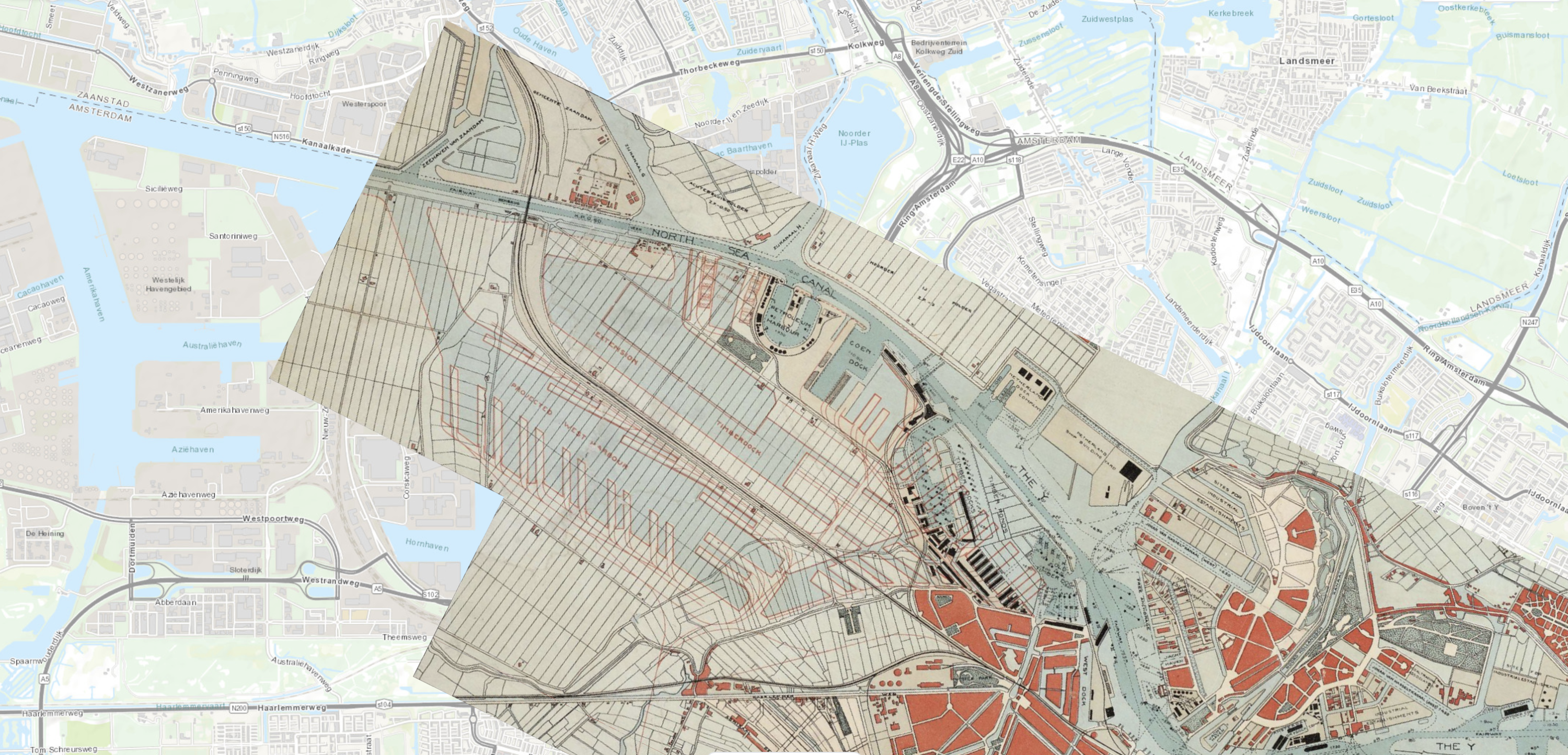

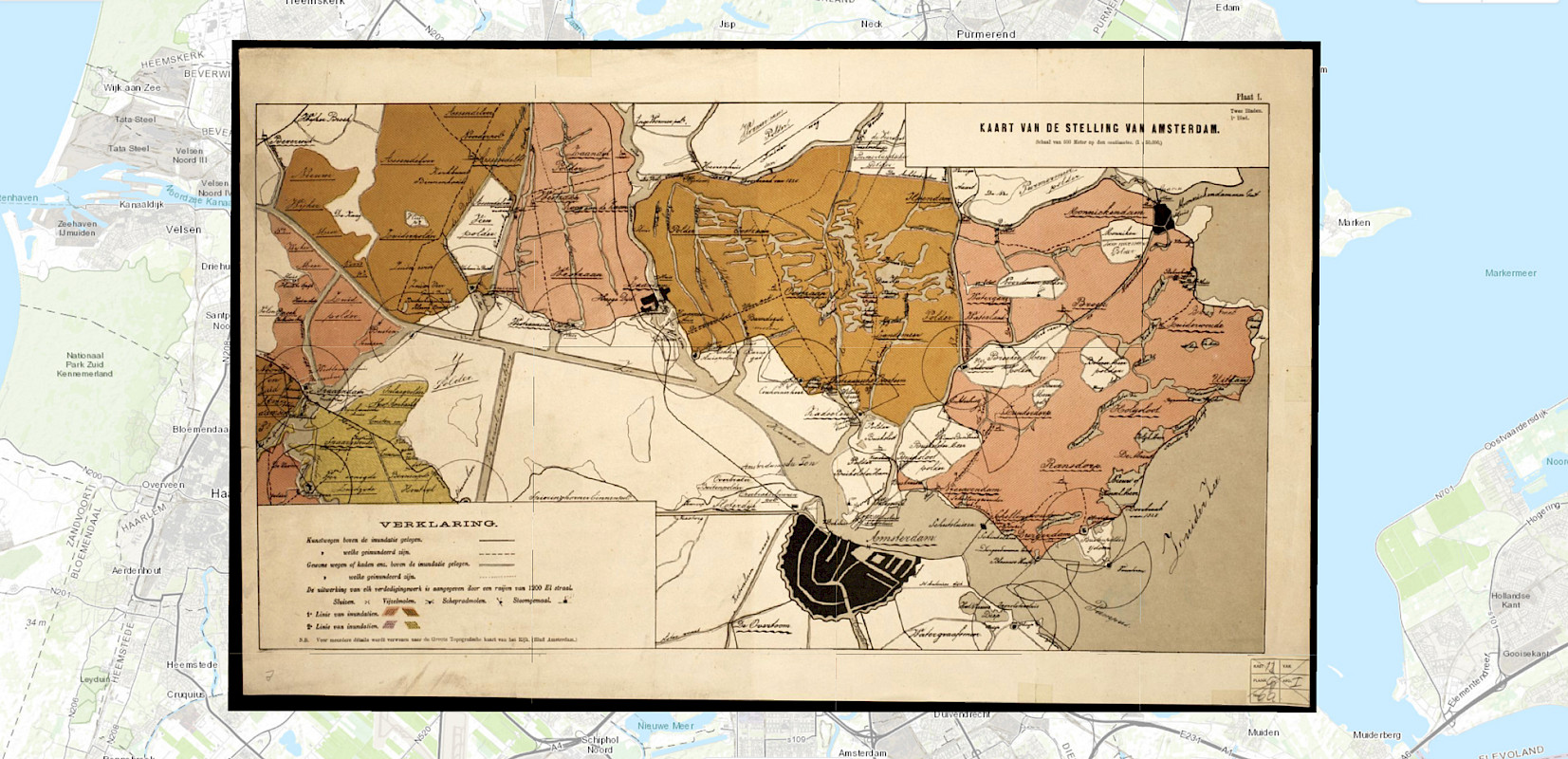

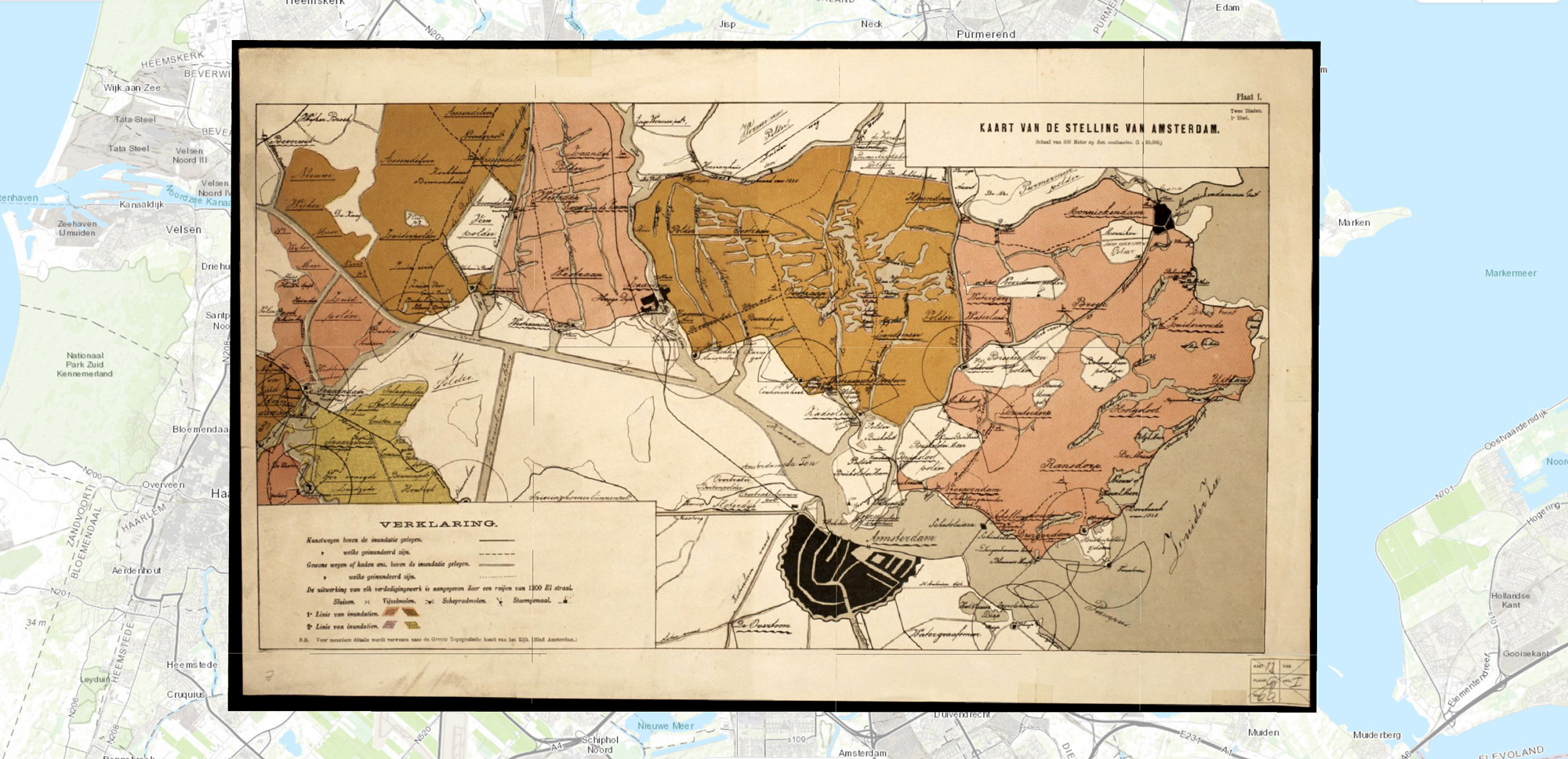

Allmaps is an open-source platform for exploring, curating and georeferencing digitised maps. Millions of digitized maps have been digitized and are available from libraries, archives and museums around the world. However, finding and using them for your own projects can be difficult and uninspiring and we aim to change that.

HH: Was your time at Het HEM during Chapter 2WO at all influential on the development of Allmaps, and if so, how? Could you see bringing the mapping method you’ve developed back to the Hembrugterrein?

BS: Only indirectly. To make enough time for the SFG project, I had to cut back on some existing collaborations and say no to other possible projects. After Chapter 2WO, I moved to the other side of the country and then COVID happened. I suddenly had enough time to think about and work on what would become Allmaps.

HH: What does a map even mean nowadays? How do you see maps in relation to how they’re used?

BS: Many people never look at maps. They just look at the navigation arrow pointing them to where they need to be. I don’t think this was so very different in the past. People always have reasons not to look at maps. But a good map will find its users. And people who are interested in maps, or simply need them, will find them.

"The modern cartographer is more a data scientist or a developer than someone who knows about geography or someone who knows how to draw"

HH: Who or what is the contemporary cartographer? The role has obviously changed as maps become increasingly symbolic and the way we visualize our relation to space becomes mediated through route planners and GPS.

BS: The modern cartographer is more a data scientist or a developer than someone who knows about geography or someone who knows how to draw. However, the basic principles of cartography have not changed: a good map is still a good map. And by using a one-size-fits-all map of the world (like Google Maps, Apple Maps, etc.) you will usually end of with a map that’s just OK for your purposes.

I think most creativity in mapmaking is found these days in data visualisation and journalism. There’s still a place for better maps!

HH: What are you working on next? What will maps become as we rely increasingly on digital tools to navigate?

BS: I’ll keep working on Allmaps for at least a few more years. The project has just started, the group of people and institutions I’m working with is slowly growing, and I still have lots of ideas. It’s my goal (and the goal of the Allmaps project) to make maps easier to find and to use. These maps can be historical maps, but there are also a lot of useful and beautiful modern maps (for example, hiking maps) that are still being made. Hopefully, by making it easier to use these maps, people will realise that there’s more than just Google Maps.