essay

The Moment You Discover Eyelashes

Laure van den Hout

Laure van den Hout writes and thinks about art. She is the director and editor-in-chief of Mister Motley, the online magazine that connects art and life. While studying graphic and typographic design and the Master Artistic Research, both at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, she discovered that language is her material.

11

min readBlack-and-white. A moving image. Frontal. Dark hair. Eyes open wide. Inside. Close-ups of the face and shoes are interspersed with images in which the observer acquires more of an overview of the space. And then: something falling.

We watch it five times. After each viewing, we share our observations. With this stream of words in the back of our minds we watch it again, unearthing new things. After a certain point we let the video work play in a loop, while our conversation continues. No more breaks, a constant fall, a constant non-blinking.

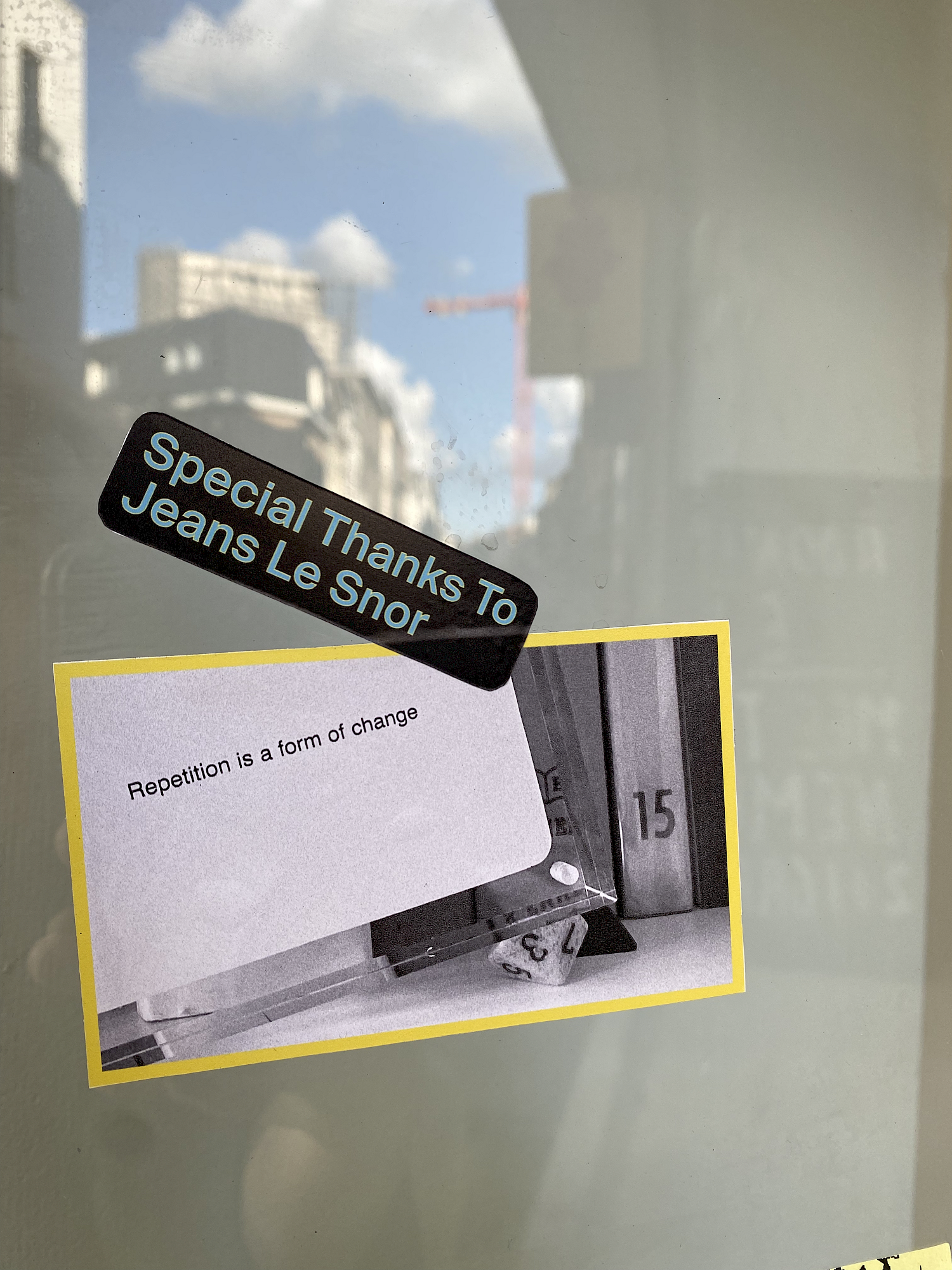

The day after I spent two hours watching the video with thirty people during Kunstsalon – a series of evenings in which people look at art, organised by Het HEM and de Vrije Academie – I am in Antwerp. As a sort of external visual memory I capture what catches my eye; which often proves to be a seed for an idea or text. That Saturday I photograph, among other things, a sticker that is stuck on the façade of the art space LLS Paleis. It’s the text on the sticker I’m interested in, that I want to remember: Repetition is a form of change. The sentence has something that both fascinates and bothers me. This is often the case when I’m not sure whether I think something is lame or actually holds a profound truth. The two needn’t be mutually exclusive, by the way. It isn’t until later on that I realize the text on the sticker and the art viewing of the night before have something to do with each other. Watching the same video work multiple times has enabled me to recognise that repetition can be a form of change.

How often do we take the time to really look at something? How often do we then decide to look at it again? I know people who re-read the same book every summer and discover something new each time. Your gaze narrows and widens, the book grows with you, which reflects in your reading – I guess it’s something like that. It works the same way for me with looking. Encountering works of art I’ve seen before is often pleasant. I recognize them, they have lodged themselves in my mind. I have made them my own, even if my gaze only rested on their surface for a mere few seconds.

In both these examples, there is usually quite some time between the first reading or encounter and the time that follows. In that time in between, all sorts of significant and mundane things happen in your life that affect the way you look at things. New associations are formed, references change, preferences shift.

When you see an artwork for the first time and go on to look at it repeatedly within the space of two hours (the video we watch is only three minutes long), very little changes regarding those kinds of external circumstances. Instead of relating what you experience as 'different' to what has happened in your life in the meantime – which briefly puts you at a distance from the work you are looking at because you are zooming out – your gaze stays with the work, you get closer and closer – you zoom in. Changes occur in what you see, precisely because you focus on what you observe each time you look at it. That which catches your attention is slightly different each time you look, your curiosity is fed and your gaze shifts. And this is insightful. For instance, when, during the third viewing, I look for where the light comes from, I suddenly see a window that I hadn’t noticed the first two times. Repetition is a form of change. You see what you hadn’t seen before. And in this case, I am even more aware of it because I am not observing on my own, but with thirty others who, by virtue of the evening's format, express their viewing experience out loud.

That it can be difficult to articulate what it is you are seeing is apparent when, after the first round of observation, the group is asked whether they want to share what they saw. It could be a feeling, object or word. 'Domestic violence.' 'Depression.' 'Tenacity.' 'Stoicism.' 'Duped.' 'Blooper.' 'Subdued.'

The answers, which may in part have been influenced by the way the question is posed ('feeling, object, word'), demonstrate how direct the path from registering to interpreting is. What we can see is that the work is in black and white, that it features a human figure who is in a space which contains a house-like structure, and that it is filmed from different perspectives. We also see the light changing. How it bounces off shiny shoes. How the human figure in the video work doesn't blink.

‘Domestic violence’ then, is an interpretation of that what is registered – a house, a collapsing façade which shatters on the human figure's head – combined with the frame of reference of the person watching. The eye sees, but it’s the mind that interprets.

Because what people indicate they see varies so much per person, a lot of interaction takes place. Sometimes this is inviting, with the other person's view providing a wider view for the group. 'We are all looking at the same thing, but see something different,' as one participant accurately observes. Sometimes the perceptions contradict each other, and while that is interesting, it is noticeable that people are quick to want to be right. It shows how rapidly perception becomes reality. The act of observing together becomes a microcosm that most of the time is hopeful. Sometimes that hope is just as rudely disrupted because people are apparently so bent on coming to 'a precise meaning' – and on being seen themselves, rather than seeing for themselves – that they don't allow someone else the space to see something different. As in society, then, it remains to be seen how much room there is for the coexistence of different perspectives. And yet I do think that looking at art collectively can be a way of making us more aware of this very issue. It is an exercise in being able to acknowledge the gaze of the other, even in situations that don’t entail looking at art, and being able to expand our own field of vision.

It would be taking it too far to call myself a participant. I have resolved to join in the conversation if I am asked a question, but I am mainly observing because I was asked to write something about this evening. Not entirely unexpected, it turns out to be difficult to look at a work open-mindedly if, at the same time, you want to keep an eye on the behaviour of those who are trying to do the same. Moreover, I used to give guided tours in museums for a long time while I was a student, and different ways of looking at art together are not altogether unfamiliar to me. That might make me a bit biased, after all, I roughly know how this goes. But however often I might have stood in front of a work of art in which everyone saw something completely different, and where 'seeing' was usually an interpretation, I have now been struck again by how people see and how important interpretation is for them. I don't know if it is true what people sometimes say, that you can't see what you don't know or aren’t familiar with, but if this evening is to be considered an experiment, it is clear that people mainly see what they know or are familiar with.

The responsibility of the viewer is not to regard the work as a universal code to be cracked, but to surrender to it, experience it, look, look again and change perspective.

So while the behaviour and dynamics don't surprise me, the evening does reveal something to me: the importance of nuance. After listening for a good while to what it is that thirty people are observing, it turns out that what is obvious to one – one person is tempted to call it 'factual' – is absolutely not to another. The work at hand, whose maker we only get to know in the second part of the evening because that’s when they join, seems to be a single take, made with different cameras. The different perspectives it thus incorporates are almost a foreshadowing of the different viewpoints this group brings to the table.

People look past what they see. Answers like 'domestic violence' and 'stoicism' make that quite clear; participants seemingly have little trouble interpreting the work. Of course, there's nothing wrong with all that interpreting and associating. Where it gets tricky is that they’re looking for one correct answer. One participant calls the evening 'a kind of crime scene investigation, playing detective together and putting the pieces of the puzzle in the right place'. Although this observation can count on sympathy and enthusiasm in the group, I still think it's a shame and that something is lost when we start looking at a work of art or art experience as a code or riddle to be cracked or solved. Crime scene investigation as an analogy for collectively looking at art mainly leads – to continue with the crime metaphors – to Clue-like questions: where, with what, by whom? Because it implies that there is a solution and it presupposes that the work of art should be able to account for itself, through the intentions of its creator or otherwise. Forcing unambiguity is not going to give you a richer art experience, quite the opposite.

Meanwhile, I sometimes look at the screen in the front of the room, where the video work is still being played. Each time it starts again, I find myself looking straight into a pair of eyes. A stern gaze, focused on the camera and by extension indirectly on me. This person is seeing something too, and that knowledge challenges my looking even more. After about forty-five minutes of talking about what we see, we take a short break. Then the person from the video work walks into the room. It turns out to be the artist herself: Aukje Dekker, who enters into conversation with us about the work and tells us its title: Deadpan Busted. The exchange leads to questions of all sorts – some more surprising and some more straightforward.

When someone asks about the artist's intention I always wonder what answer is being sought. Which response would bring real satisfaction? What makes wanting to understand something seem so prevalent over wonderment? Artists are essentially generous. Their work is a world that can be experienced by a very diverse range of viewers in just as many ways. The responsibility of the viewer is not to regard the work as a universal code to be cracked, but to surrender to it, experience it, look, look again and change perspective. After all, repetition also means assuming a relationship with something over and over again – sometimes involving both the work of art and the artist, and sometimes involving only the work of art – which makes it take on a form of change.

'She discovered my eyelashes today,' a friend texted me a while back about her near one-year-old child. As I write this, I am suddenly reminded of that message. Looking at the world through new eyes and slowly using those eyes to look at the eyes of others. And then not yet trying to read, fill in, interpret the space behind it, but just being mesmerized by that fan of hairs which is supposed to keep the field of vision as open and undisturbed as possible. Seeing the other person see you. After an evening of observing together, it turns out there's not a lot that is actually normal about that. There is a moment when you will discover eyelashes. But that doesn't mean you don’t see anything until that point. You see other things. The space between looking and interpreting might well be seeing. And while the crime scene investigation analogy seemed to do well in the group, I myself like to spend a bit more time in the space in between. To see for myself first.

***

Editor's Note: The work of art that took centre stage at Kunstsalon attended by Laure van den Hout on 22 September is Deadpan Busted (2017) by Aukje Dekker. The sticker with the text 'Repetition is a form of change' is a work by Valentin Garcia and was part of the exhibition Entrouverte, curated by Ghent-based collective 019, and which was on display until 22 October at LLS Palace in Antwerp. This essay was originally written in Dutch and was translated by Isadora Goudsblom.