fiction

Lungs

Isa Mazzei

Isa Mazzei is a writer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles, fascinated by the intersection of technology, identity, and horror. She graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in comparative literature and went on to write and produce Blumhouse’s film, CAM, now on Netflix. Her writing has been featured in New York Magazine’s The Cut and Glamour. Her memoir, Camgirl, was named one of NPR’s best books of 2019. She is currently in post-production on an adaptation of Faces of Death for Legendary Pictures.

fiction

I Become You

“I love your face. I guess if I had to look at it every day, it wouldn’t be the worst.”

Hussein Shikha

Hussein Shikha is a multidisciplinairy artist, graphic designer, writer, and researcher based in Antwerp.

fiction

I Become You

“I love your face. I guess if I had to look at it every day, it wouldn’t be the worst.”

15

min read

Cassidy did not expect to see lungs today, but there they were: pink, veiny, and just the smallest bit bloody.

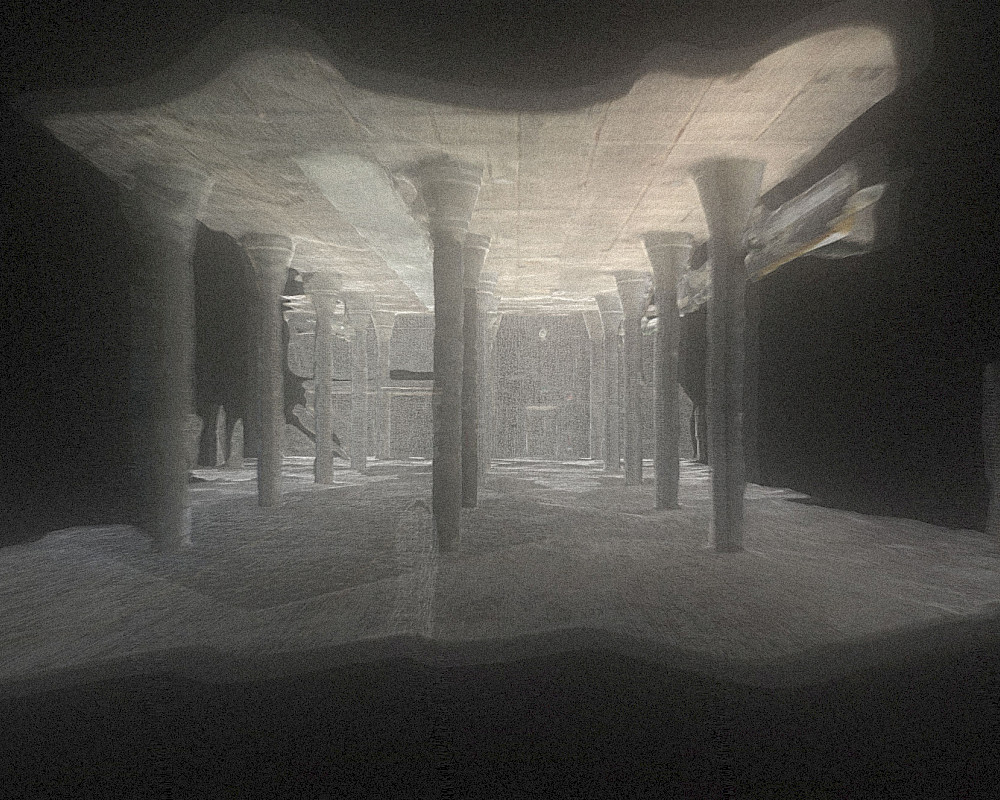

“At least they’re breathing?” She ventured optimistically, trying to look away from the CCTV monitor. The lungs lay center stage, underneath the yellow glow of the sodium vapor lights the company had hung after too many clients started getting hysterical. The soft light was supposedly soothing. It recalled childhood nights playing under street lamps and night time summer strolls in hot, humid air. Whether or not they actually worked was a different story, but right now, Cassidy’s boss, Jazzy, was a little more concerned about the quivering lungs that had appeared, seemingly, out of nowhere.

“Well go in there!” Jazzy ordered, as if it were weird that Cassidy hadn’t immediately jumped to her feet and ran into the theater at the first mention of “disembodied lungs”.

“What do you want me to say?” Cassidy asked, thinking of the client. Mrs. Parker had been a regular for eight months now, which wasn’t actually that long in the scheme of afterlife theaters, but she had quickly become their most frequent client. She booked a slot almost every day, and if they had a cancellation, they knew they could rely on her to fill the gap. On screen, Mrs. Parker remained frozen in her front-row seat, her hands grasping the red velvet armrests of the chair.

“I don’t know, but just get in there before she asks for a refund!” Cassidy let out a long sigh, but she headed towards the theater.

“You can’t work in one of those places!” Cassidy’s mother’s reaction had been more or less what she expected when she told her about the job she’d gotten right out of high school. “You want to be an astronaut, shouldn’t you pick something more in line with what you’re going to study? You always wanted to travel and explore. You watched so much Star Trek!” Cassidy had tried explaining to her mother that “astronaut” was not a real job anymore, and most people who studied astrophysics ended up just doing math. Lots and lots of math. Cassidy wasn’t even sure she wanted to go to college anymore, but explaining that felt a little too complicated. So she told her mom she wanted to save up, and Jazzy’s was the place to do it.

Jazzy’s Afterlife Relations was the cheapest of the theaters in all of Chicago and the surrounding areas. For only $1 a minute you could talk to your deceased loved one in a “glamorous” setting. Sure, the theater was run down, and the red velvet curtains and upholstered chairs felt dated and shabby, but Cassidy felt like if she had worked at any of the swankier places, that might have been exploitative. I mean, Review Life charged $46 a minute and they didn’t even offer a no-show guarantee. That felt wrong. At least at Jazzy’s she was, in a way, giving back. Allowing catharsis for those with a normal amount of money. And she was pretty good at getting people’s loved ones to show. Usually they didn’t need to pay for more than ten minutes a pop, unless they really wanted to dig into some family drama or something. Even Jazzy admitted Cassidy had a knack for it.

“I wish you’d been here from the beginning,” she had said, after Cassidy’s fifteen-session summoning streak. “You could’ve saved our Yelp reviews.” But now, faced with quivering lungs and a terrified Mrs. Parker, Cassidy definitely felt like their Yelp reviews were destined to take a hit.

“Mrs. Parker, why don’t you go enjoy a complimentary beverage in the lobby while I take care of this?” Cassidy asked, gently placing a hand on Mrs. Parker’s shoulder. She generally didn’t touch the clients, in fact, she was pretty sure it was entirely against the rules, but she needed to find a way to direct Mrs. Parker’s gaze away from the pink, shining mess on stage. Up-close, the lungs looked somehow less real than they did on the security cameras. There was something so jarring about seeing organs in this context that it felt as though Cassidy’s brain couldn’t quite parse this new reality. Like it refused to show the lungs in focus, or something.

“That… those… they aren’t… his, are they?” Mrs. Parker asked, finally turning her head and accepting Cassidy’s help towards the aisle. With the house lights on, the carpeting looked particularly worn and sad, fraying at the edges and with stains that no amount of steam-cleaning was ever going to get out.

“Of course not, Mrs. Parker, absolutely not.” Mrs. Parker did not look convinced, so Cassidy added, for good measure, “we clearly just need to recalibrate a few things and we’ll have Mr. Parker here for you tomorrow, right as rain.”

“Has this happened before?” Mrs. Parker asked, turning doubtfully back towards the stage as the two reached the exit.

“Oh all the time,” Cassidy lied, as she delicately steered Mrs. Parker through the double doors and out into the harsh fluorescent light of the lobby. “Don’t worry about it.”

Later, back in the main office, Cassidy and Jazzy stared into a trashcan, which now held, among the popcorn, soda cans, and used tissues, a pair of lungs. Inexplicably, they still moved. Not quite like they were breathing, exactly. But not like they weren’t, either.

“Maybe the animal afterlife got mixed up with the human afterlife?” Cassidy offered. The animal afterlife was notoriously hard to access. The places that could reach it charged $100 a minute and even then they had an astronomical fail-rate.

“Do those look like animal lungs to you?” Jazzy asked. Cassidy peered closer. They didn’t, but then again, the closest frame of reference she had were sheep lungs from high school biology. Mr. Vertenstein had plopped a pair on his desk, shoved a purple crazy straw down the trachea and had blown, inflating the lungs and eliciting squeals and terror from the gathered students. Maybe these were just lungs from a bigger animal. Like a gorilla. Or a zebra.

“Don’t you think we should report this or something?” Cassidy felt Jazzy bristling beside her. She stood upright and abruptly yanked the black trash bag closed. Jazzy never touched the trash, so Cassidy knew she was serious.

“Of course not, don’t be stupid,” Jazzy yanked the entire bag out of the trash cash, tying it off with a deft gesture and then passing the whole thing to Cassidy. “Take this out.”

As Cassidy dumped the lung-laden trash in the dumpster behind the theater, she took in the decrepit parking lot, the rusting sign, the blades of grass stubbornly trying to carve out a home in between the asphalt cracks. Maybe her mom was right to be appalled that she was working here. It wasn’t exactly glamorous. But when she thought about her other options, bussing in a restaurant or folding shirts at the downtown J. Crew, she shuddered. At least here, she was helping people. No one really expected much of her either. It was the first time in her life she felt like no one had any expectations to live up to. Now that school was over, there were no deadlines, no assignments, no one waiting for her at her locker to force her to gossip about whoever. Cassidy could just exist. She could finally breathe. She didn’t fully understand why people elected to go back to school once they were free of it.

Cassidy took a second to stare across the smoggy Chicago skies, bid goodbye to the lungs, and hoped this would be the end of it.

Two days later, she found herself staring at an arm. A definitely, definitively human arm.

“Well, take care of it!” Jazzy ordered her, exasperated. “We have an entire bachelorette party coming in at 4. They want the bride’s dead father to bless the union, and if we get blood on any of their outfits I just know they’ll be showing up for weeks with dry cleaning bills.”

Cassidy knelt down with a plastic dustpan and broom. The tools were woefully inadequate for the job, but the thought of touching the arm, even with gloves, felt viscerally repulsive. Cassidy gingerly prodded the arm towards the cracked plastic, until it was fully balanced in the middle, limp wrist dangling from one end, bloody elbow hanging from the other. Cassidy looked closely at the arm for any identifying features—a mole, a tattoo—but it was extremely generic. She wasn’t even sure if it belonged to a man or a woman. She dropped it in the trash.

Jazzy was pacing in the hallway. “That better be the last time that happens,” she said, to Cassidy, but really to one in particular. Cassidy nodded and walked back to the supply closet to drop off the broom and dustpan. She thought she should probably disinfect them, but it was an afterthought, and the supply closet door was already closed and locked.

That evening, as she summoned someone’s dead girlfriend, she sat behind her shield near the void machine and closed her eyes. The night before, Cassidy had told her mom she didn’t want to go to college.

“Then what are you saving for?” Cassidy couldn’t fully explain it, but it turned out she didn’t need an answer, because her mom had kept right on lecturing her. “I am not paying for you to live here, you’re an adult. You’re eighteen. I told you I would support you as long as you were on a path towards something, a career, but you’re not going to live here and rot. My parents pushed me out at eighteen, don’t think I won’t do that to you too. Figure it out!”

With the blonde, freckled teenager safely on stage, Cassidy took her leave of the theater to give them their privacy. The kid came in every Friday to update his dead girlfriend about the week. She knew he was using his allowance because he always paid in cash and only ever paid for exactly eight minutes. She wondered if his family knew he came. She wondered how long it would be before he moved on, found someone else. She wondered if Jazzy knew he only summoned his girlfriend so they could fuck. She wondered what it was like to fuck a dead person.

Over the next few weeks, more and more body parts started appearing in the theater. Fifty percent of the time they got a person, and the other fifty percent of the time, they got a random limb or a disembodied liver. Jazzy tried interrogating the next intact person who came through, a twenty-four year old named Brody, but everyone knows dead people are incredibly unreliable narrators. He was more concerned about how the Eagles were doing this season, and his weepy mother was more concerned about if he was eating enough vegetables in the afterlife.

The following week, it was up to seventy-five percent dismembered body parts, and at this point, Jazzy started getting outrageous ideas.

“Someone, or something is tearing these people apart,” she remarked, casually holding up a pair of human kidneys. One of them looked as if it had been chewed through. She tossed it into the trash. “You’re going to have to figure this out.”

“What?” Cassidy stopped, mid-spray, holding a bottle of bleach in one hand and a mop in the other. She was cleaning up after some particularly messy intestines, a task which, at this point, had her just about ready to beg for the job at J. Crew.

“I had to do twenty-eight refunds this week. Twenty-eight! It’s just not sustainable.” Not to mention all the new sanitation procedures Jazzy had insisted they put in place now that word was getting out about their little “problem.” Cassidy had doubted that soothing clients with promises of Clorox and UV sanitizing lights would really mitigate the effects of a full human jaw appearing on stage instead of Great Aunt Irene, but she was a good employee. And obedient. Usually.

“I have to send you through to investigate.”

“I’m sorry, what?”

“I need you to fix this,” Jazzy said, peeling off her gloves into the scented trash bag.

“You want to send me to the afterlife?” Cassidy was unqualified for a lot of things, but this, in particular, felt out of her wheelhouse. “Has anyone ever done that before?”

“No, but we send dead people back all the time, so I don’t see why it wouldn’t work.”

Cassidy could see a lot of reasons why it wouldn’t work. She might die, for starters. The void machine was literally covered in WARNING: LIVING ORGANISMS STAY BACK 200 FEET stickers. They had to install a special shield and everything just to use it.

“I can’t do that. No way.” Cleaning up detritus was one thing, but this was another.

Jazzy eyed her, disappointed, but clearly realizing that pushing it would probably not only be a labor violation but also possibly a crime. “I’ll give you a raise.” Jazzy plucked the trash bag from the trash can and passed it to Cassidy without much ceremony. “And a promotion. Think about it. You’d have more than enough money to pay for your semester.”

That night, Cassidy arrived home to find her mother gone. Probably working a double. Cassidy knew that was the real reason her mom was so unhappy about her bailing on college. It wasn’t about being responsible for herself. It was about giving her child a better life than she had. Her mom worked hard cleaning office buildings after all the employees had left. If she knew that Cassidy had basically been demoted to cleaning theaters, it would probably break her heart.

Cassidy picked at some microwaved tamales and stared at the fridge. It was still covered with her childhood drawings, many of them faded now, bleached by the gentle morning sun that fought its way through the tiny windows. She stood and took a drawing off the fridge. She had made it when she was six, a tiny crooked rocket ship heading for the stars. “My name is Cassidy and when I grow up I want to be an explorer” her teacher had written in a swirling orange crayon across the bottom. Cassidy had never noticed how much her dream had infused the entire household. The kitchen was decorated with an ornate compass wall piece her mother had found at Goodwill. The living room had a model rocket gifted to her for Christmas, and her bedroom was wallpapered with vibrant purple galaxies. She had always wanted to explore the unknown. To go somewhere else.

The next morning, she found Jazzy hard at work diluting the slushie syrup with distilled water. She said it made them taste better, but Cassidy knew it was a lie. It didn’t really matter, it’s not like anyone who came to the theater complained about the watery drinks.

“Okay,” she told Jazzy. “I’ll go.”

“Great,” Jazzy grunted, holding out her hand. “Pass me that jug, will you?”

Half an hour later, Cassidy found herself standing on stage. The orange glow of the sodium vapor lights was disorienting. From here, she could take in all the empty red chairs, the peeling wallpaper, the dust that was collecting around the handrails. At least the void machine was new. Relatively.

“Ready?” Jazzy’s chipper voice called out from the projection room next to the void machine.

Was she ready? She wasn’t sure. But she knew what awaited her if she stayed. That afternoon they had booked in two widows, the sole survivor of a car crash, and a bunch of lawyers hoping to resolve a custody case. Not to mention whatever body parts decided to show themselves. She might not be ready for what was coming, but she was ready for something different. Plus, Jazzy had promised to pay her time and a half. Couldn’t argue with that.

“Ready.” Cassidy took a breath and steeled herself. Even from here, she could hear the soft hum of the void machine as it started up. She wasn’t sure what it would feel like. When they sent people back, it was almost like a gentle poof and they would vanish. It seemed instantaneous. She hoped it wouldn’t hurt.

“Alright, I’m hitting it,” Jazzy called out. Cassidy could almost see her finger hovering over the button, as if there were a countdown. She could smell the faint metallic smell the void machine gave off when it sent people back. Five…four….

Cassidy stood up a little taller. Three… two…

She was ready to go through the void, to explore, to set foot where no man had gone before. Or, at least, no one living. Hey, she thought. At least it’s better than J. Cre–