essay

The distant bungee jumper, a dangling herring

Charlie Jermyn

Charlie Jermyn is a writer, essayist and performer from Dublin living in Amsterdam. His works include aural odysseys on landscape and art, the dissolution of bowling alleys, perambulation across nations, and travel writing from Balkbrug to Hong Kong, Dublin to Pavia. He is a monthly resident at Stranded FM Utrecht with his show More Poetry is Needed, where he has explored the poetic works of Arthur Russell, John Cooper Clarke and Van Morrison.

essay

A neon palindrome, lessons from the crouching man

“In the name of contemporary art, Spain has finally embraced the whitewash technique of the iconoclasts.“

essay

A devilish grin, a suburban carpark

Essayist and poet Charlie Jermyn makes a do-it-yourself pilgrimage through museum, muck, rain, wind and pub to visit Jan Steen’s old haunts

essay

Two Nights of Noise at Tivoli

By recounting his experiences of two formative concerts at Tivoli, essayist and performer Charlie Jermyn provides a poetic account on the raw power of sound and the music of everyday life. He connects the origin of noise music to Italian Futurism, a movement fascinated with dynamism and constant innovation, and appreciates the ongoing vitality of aging cultural icons amidst the decay of our time.

Mel Keane

Mel Keane is a designer and artist based between Ireland and the Netherlands, focusing on the media of drawing and music composition. His practice draws from a wide variety of sources, including folklore, metaphysics, and experimental music scores.

essay

A neon palindrome, lessons from the crouching man

“In the name of contemporary art, Spain has finally embraced the whitewash technique of the iconoclasts.“

22

min read

“The landscape disturbs my thought,’ he said in a low voice. ‘It makes my reflections sway like suspension bridges in a furious current.’[1]

—Franz Kafka

The tramline from The Hague to Scheveningen opened in the summer of 1886. The trams were steam-powered, chugging along, pluming smoke as they snaked the seven kilometres out to the strand. People at the time experienced a new development in the technology of convenience — fresh modernity — where the surging tide of progress was washing up onto the beach.

Scheveningen and its strand, historically, has been the stage for moments of historical comings and goings, like the lapping of tide, ebbing, flowing, swaying, shifting. The place has seen exiles, shipwrecks, great floods, sea creatures, herring, painters, artists, writers, seabirds and, in the summer of 2022, my dad and me.

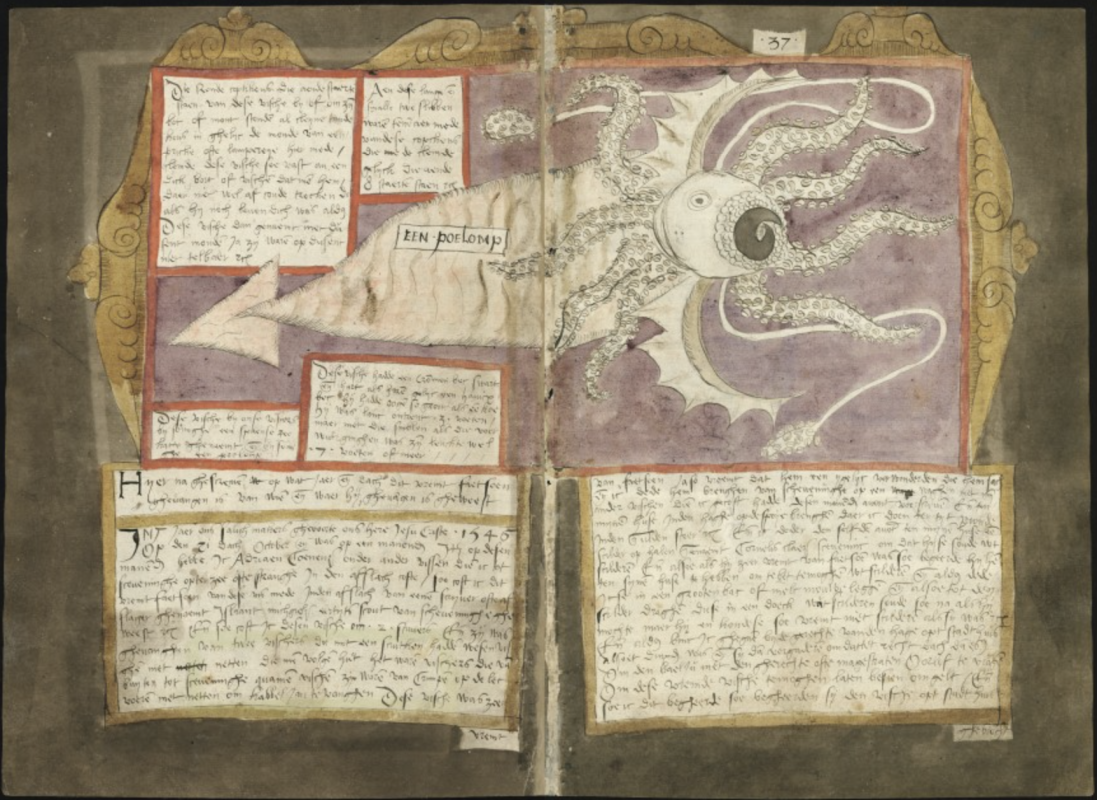

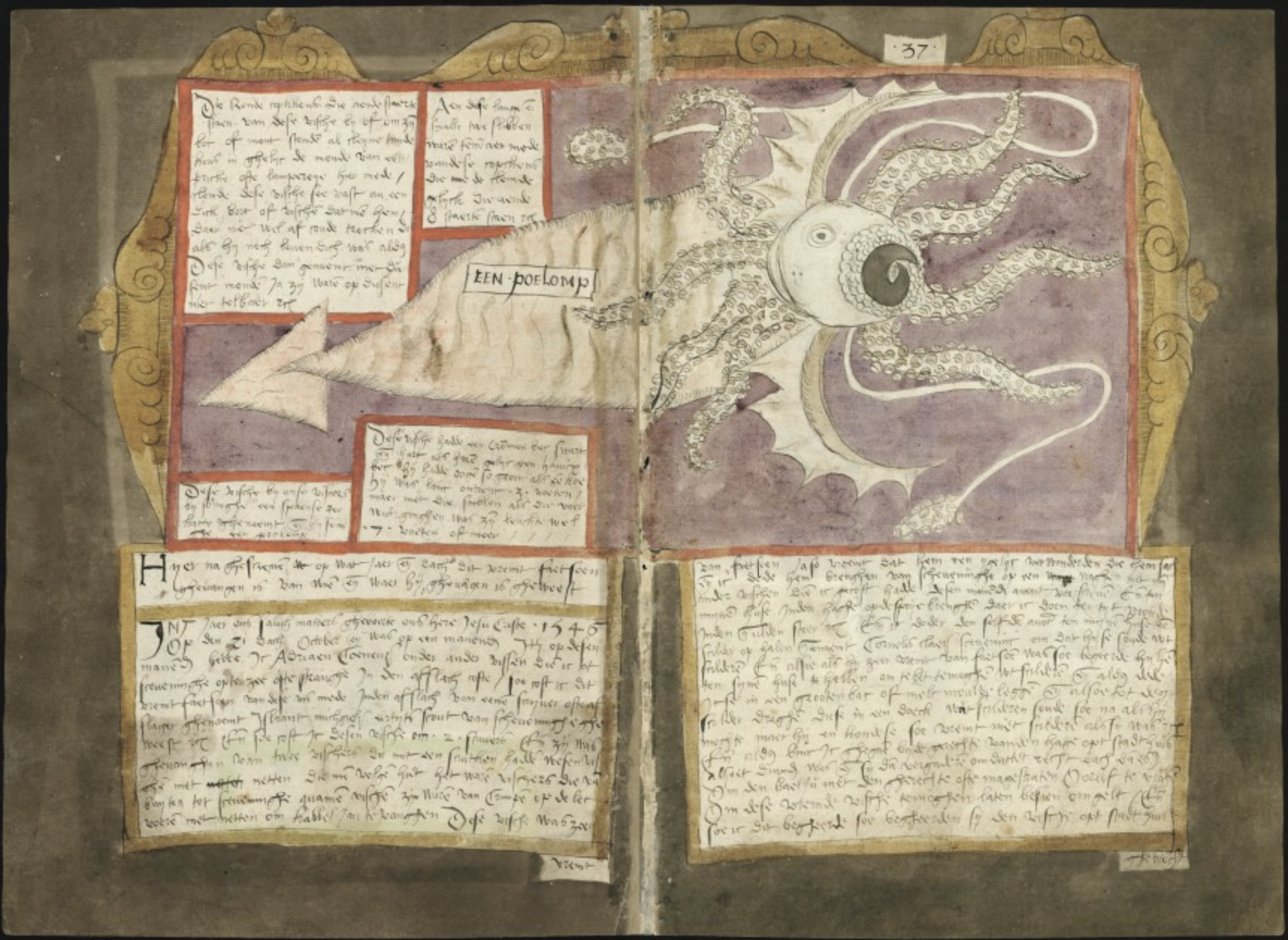

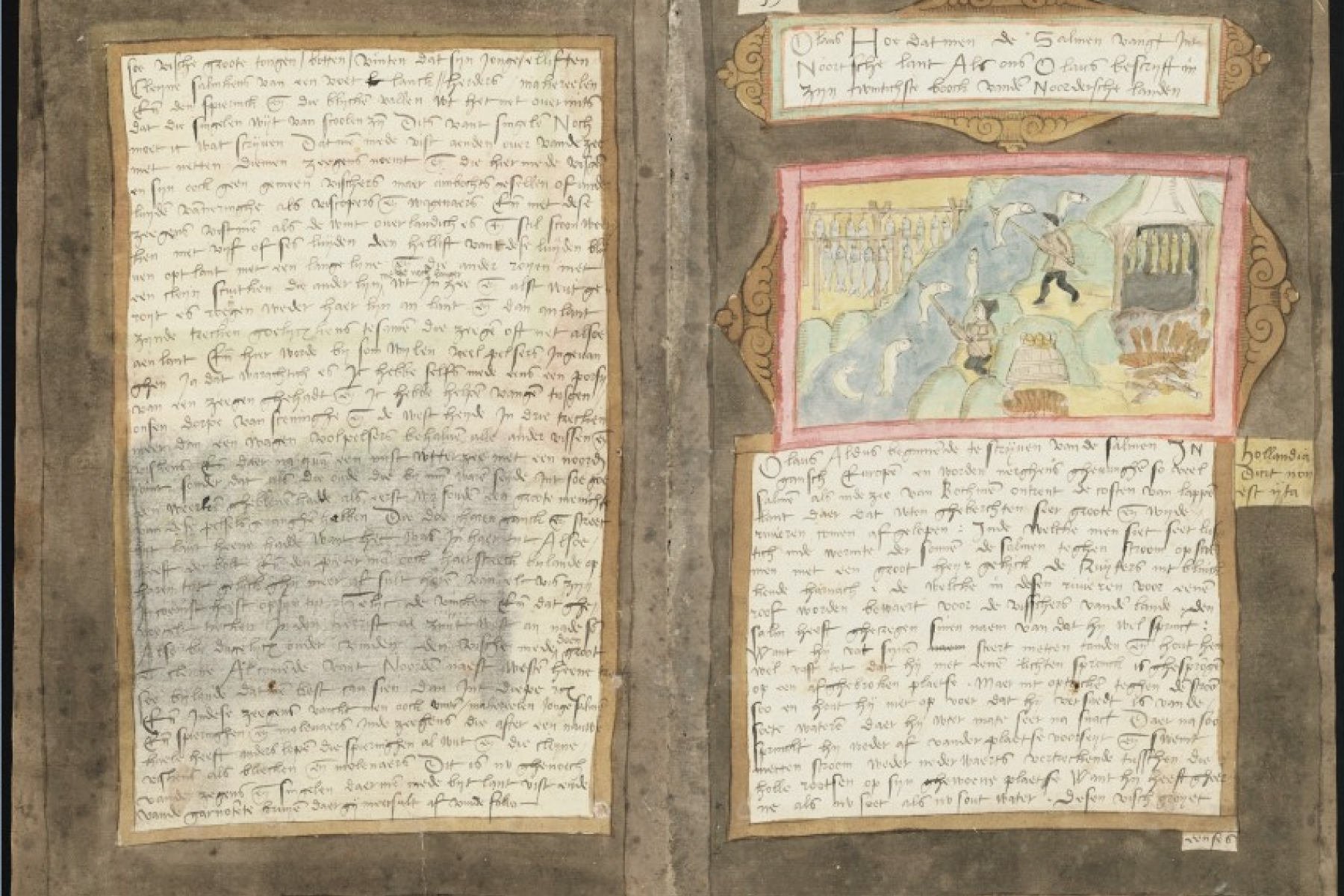

The earliest mention of the town was in 1280. In the centuries thereafter, the years of dredging and carving out a civilization, it grew steadily into a fishing village. In 1579, the town was documented extensively by a local fishmonger called Adriaen Coenen. He produced an illustrated manuscript called Het Visboek, depicting sea creatures and seafarers. Coenen meandered from the real to the mystical, butterflies to ghosts, dolphins to dragons, chimps to unicorns. Kelp-haired mermaids floating up onto the sands, as plagues of mice scattered, chewing through wheat on barges. There were seabirds the size of ships.

Drawing from the myths and legends of sailors, Coenen imagined a hideous cyclops, a fish so giant it swallowed a fleet whole, and ‘een poelemp’ — a fierce monstrous being with a daggered tail, the head of a sucking octopus, a gaping mouth, tentacles thrashing. All beasts were murky visions hidden beneath the North Sea waves.

He painted water spewing from blowholes, tails breaking the waterline, a thousand shimmering scales, and the beached whale in the Drowned Land of Saeftinge which the village folk hacked into for blubber.

Coenen detailed the daily lifestyle of fishermen; the correct usage of a harpoon; the technique of flinging nets; the process of smoking a herring. He asked practical questions. Where can you buy a certain fish? Is this creature edible? Can I sell this crustacean at market?

You can read about the mythical ‘Herring King', seen in swift passing moments by sailors. It is thought Coenen was describing the giant oarfish, ribbon-like and crimson, about ten feet in length. The regal name comes from its spiked, crownlike appendages. The fish undulate like serpents at depths of up to 1,000 metres, and swim vertically upwards until the crown breaks the surface. The herring holds an almost magical power in the town. The flag of Scheveningen features three silver herrings wearing gold crowns on an azure background. In 1622, the playwright and poet Joost van den Vondel wrote a brief ode to the herring and the herring industry:

“O what a golden industry is created for us by that food, the royal herring. How many thousand souls, thank God, live by this trade and earn a living from it.”[3]

The seas near Scheveneningen were battlefields in the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Slag bij Ter Heijde, or the Battle of Scheveningen, was fought between English and Dutch fleets off the coast of the village in August 1653. Locals gathered on the shore to watch. Warfare lit up the sky. The horizon glowed aflame, the crack of cannon fire rippled over the water. Both navies suffered catastrophic losses, both claimed victory, retreating with the wounded towards Dover and Texel.

In the National Gallery of Ireland in 2022, there was an exhibition: ‘Dutch Drawings: highlights from the Rijksmuseum.’ On display, there was a panorama drawing from the Rijksprentenkabinet by Jan de Bisschop, depicting the departure of Charles II for Dover from Scheveningen in 1660. Oliver Cromwell had died in 1658.

Cromwell, the warts and all leader, and his supporters the Roundheads were violently against the divine right of kings. They chopped off Charles I’s head in 1649. The orphaned Charles II was living in exile in Holland and as depicted by Bisschop, was setting sail for the Restoration from Scheveningen. The monarch was picked up with pomp and circumstance to bring him home. Once back, the king declared the ‘Act of Indemnity and Oblivion’ where nine of the regicides were hunted down and executed. The body of Cromwell was exhumed and received a posthumous decapitation.

Scheveningen was, and still is, battered by North Sea storms. From the 17th to 19th century, floods repeatedly washed the town away. At the end of the nineteenth century, a harbour was constructed to protect against the flashing floods. Until then, bomschuiten, boats with a flat bottom were hauled up onto the beach. Once the harbour came into being, modern boats replaced them. The village attracted Dutch artists over the centuries, who painted the bomschuiten drawn up on the beach, or fishermen at work in the North Sea.

The hotel Kurhaus was opened in 1886; steadily more tourists came to the town. One of the tourists was Irish writer James Joyce, who stayed for one month in the Netherlands in the summer of 1927 – the year the trams rolling in from The Hague were electrified. There is a story where Joyce was lying on the beach reading a guidebook, searching for the Hook of Holland when suddenly, he was mauled by a dog. The dog’s owners tried to pull the hound off Joyce. In the human-canine melee, Joyce’s glasses disappeared in the sand, and were found later, cracked and bent.

The Hague School

From 1860, the changing town of Scheveningen attracted artists, painting stark dichotomies: fishermen and tourists; dunes and polder lands, horses and trams, Oorijzers (the traditional hats worn by local women) and top hats of the budding bourgeoisie.

The hotel Kurhaus was opened in 1886; steadily more tourists came to the town. One of the tourists was Irish writer James Joyce, who stayed for one month in the Netherlands in the summer of 1927 – the year the trams rolling in from The Hague were electrified.

A collective of artists formed The Hague School in the 1860s, influenced by the French Barbizon school, a French collective named after the forest of the same name near Fontainebleau. The artists wanted to paint things as they were. The Hague School saw the work in academies in France and Belgium, before carrying the same artistic ideals north to the Netherlands. The group’s mission was to combat the idealized and utopian natural world depicted by the art academies of Europe. The Dutch landscapes of the past (like those of Jan van Goyen discussed in my last essay) conjured up images of dunes, estuaries, roaring seas with keurlijk natuurlijkheid, a selective likeness to nature. For van Goyen and his contemporaries in the Calvinist Lowlands, the new divine was nature: Wind whipping up, capsizing boats, the menace of darkening storm clouds, a break in the clouds. The Hague School wanted to paint realistically. Through landscapes, seascapes and depictions of nature en plein air, their realist landscapes are synonymous with the visual representation of a budding Dutch national identity: Towns, strands, flat horizons, windmills, polders, livestock, canals, and developing industry.

Viennese writer Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) captured the sentiment of this threshold period in his 1942 memoir ‘The World of Yesterday.’ For Zweig, there was a new source of divine devotion: not to nature, but to boundless invention and reinvention, where “uninterrupted, inexorable ‘progress’ truly had the force of a religion. People believed in progress more than in the Bible, and its gospel message seemed incontestably proven by the new miracles of science and technology that were revealed daily.”[4] The momentum of progress was only accelerating. Streetlights replaced dim lamps illuminating the boulevards that ran through cities all the way out to new suburbs. The telephone brought people together, the trains took them further away. Higher speeds were achieved with steam powered engines, and landscapes shrunk. As Zweig writes, we were even “fulfilling the dream of Icarus by rising in the air.”[5] The Hague School were capturing this period of great cultural and societal upheaval:

“Suddenly the old, comfortable order had been disrupted, its norms of the ‘aesthetically beautiful’ were questioned, […] we young people flung ourselves with gusto into the turbulent waves wherever they broke and foamed most wildly.”[6]

Only in the middle and second half of the 19th century did Dutch polder landscape painting, the nature carved by human hand, emerge as a serious genre. Artists painted polder scenes in an impressionist style, a reaction to urbanization and industrialization. They celebrated a landscape that was occupied by large-scale processes of change. Like their 17th-centruy predecessors (van Goyen et al.), they revealed a new cultural imagination and identity.

A strand of arrivals and departures

In the Rijksmuseum, there is a room dedicated to Dutch art in the 19th century, with a series of paintings by members of the Hague School. Maris, Mesdag, Constant Gabriël, Mauve, all played a massive role in creating the modern image of the Netherlands: cows, lowlands, polders, the curvature of the earth in the wide, unobstructed view of the horizon. Constant Gabriël writes: “Our country is coloured-juicy-fat. (...) I repeat, our country is not grey, not even in grey weather, nor are the dunes grey.” Gabriël was one of the few who chose to stick with colour. In Jacob Maris’ Arrival of the Boats from 1884, we are presented with realism, a truly grim day.

Staring at it, I placed myself standing, waiting with the fisherman on the horse. The weather bashes us so much so the paint on the canvas cracks. A haul of fish arrives on the Scheveningen strand. Gulls fly through a sky of luminous grey. The boats are battered, the crowd in front wonder if there will be fish; they do this every day, religiously. The bomschuiten boats will be hauled up by horses. A resounding brown colour pervades this painting; the white crashing waves, the Oorijzers and the far-off horizon are the only specks of brightness. Maris has another work in this room, The Truncated Windmill (1872).

In this work, we are on the Noordwestbuitensingel, away from the fishing village. The view is from the painter’s studio window. There is a bridge over a mud brown canal. An old figure, a spectre, crosses over to the other side. A breeze blows over the land, the windmill creaks, its sails slowly starting to spin.

A breeze blows over the land, the windmill creaks, its sails slowly starting to spin.

Anton Mauve’s work The Marsh is visible in the same room. We are presented with shadowy sea birds floating over a flooded field of grass. The area is the hinterland behind the dunes. The sky is impossibly grey but for a setting sun, weakly breaking through the clouds as twilight nears. Here, Mauve paints the swamp, the dirt, the stagnant bottomless bogs swallowing old boots. Wetlands crisscrossed by creeks and brackish swamps. A fragment of a world beyond the canvas, life bubbling under, and a vision of such tracts of land before they were filled in. Now, there is almost none of that marshland left. For in this small country, space is there to be occupied.

Hendrik Willem Mesdag was another member of the Hague School. At the turn of the twentieth century, he painted the Lighthouse of Scheveningen in foreboding darkness, the night lit by sea froth and spray rising into the sky. The minute lamp tirelessly shining, almost indistinct in yellow, guiding ships back into harbour.

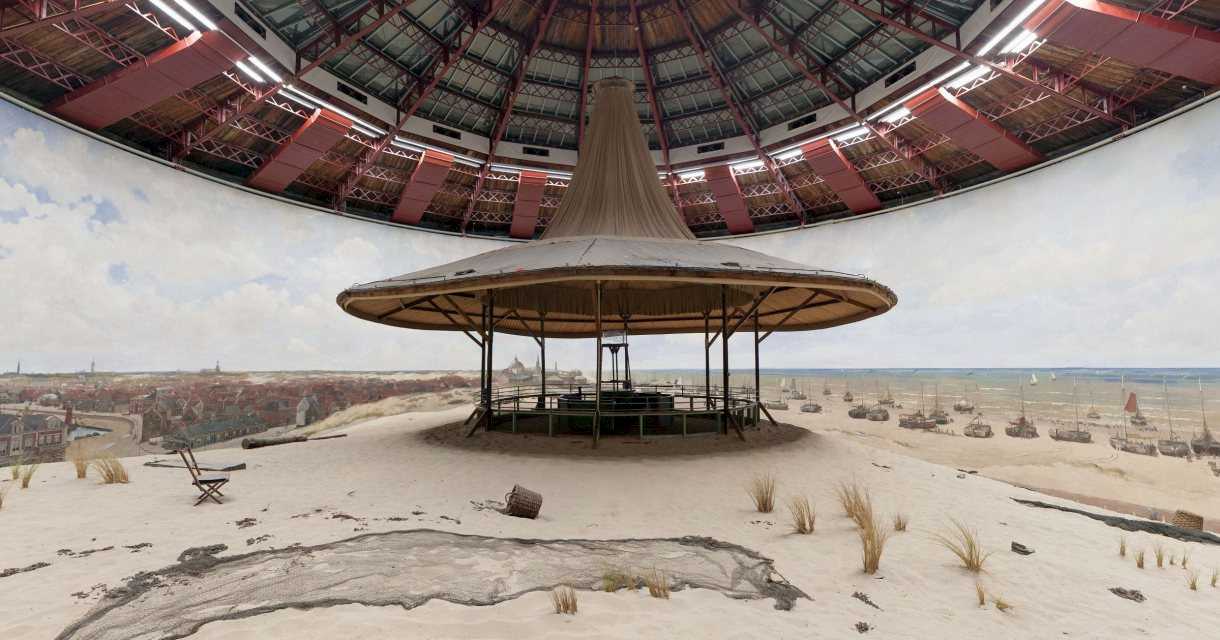

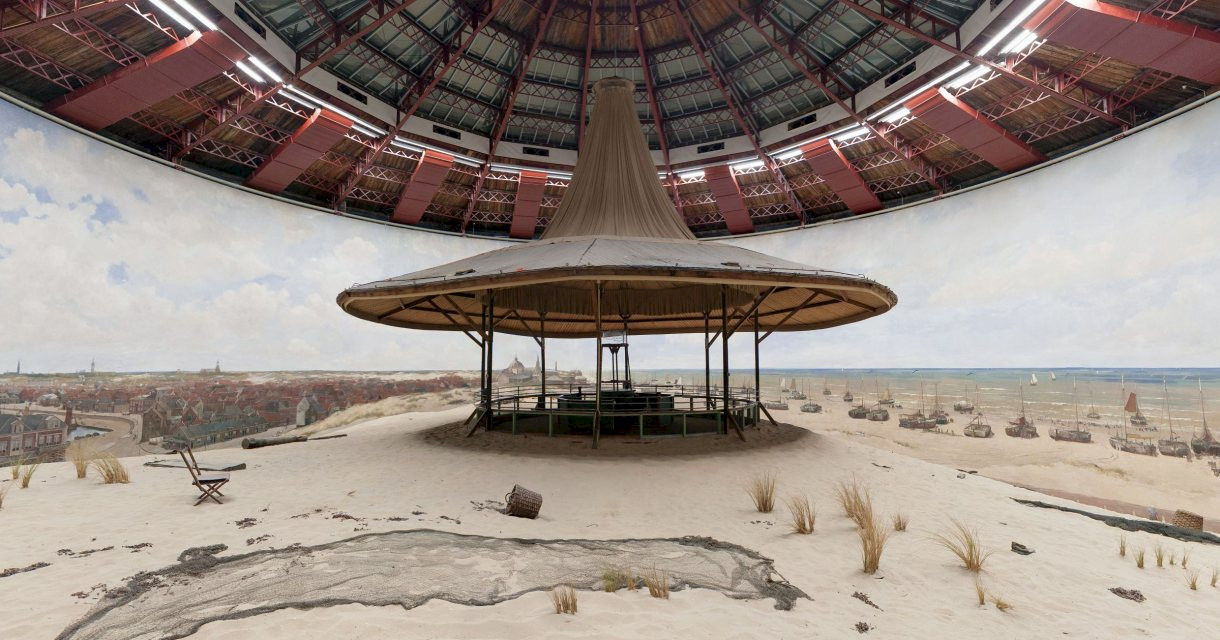

Mesdag’s most famous work is the Panorama of Scheveningen from 1881. The painting is a cyclorama, a cylindrical immersive painting that surrounds the viewer. Panoramas were hugely popular at the end of the 19th century, like early cinema or a virtual reality. At the foot of the panorama, the floor is filled with sea detritus, nets and artificial sand so the viewer can completely absorb the 15x120-metre painting in the round.[7]

Vincent van Gogh painted the strand in August 1882 under Mauve’s guidance. The artists were related by marriage. Van Gogh painted furiously and fast, en plein air, the wind nearly knocking over him and the easel. Upon finishing the work, the artist tried to scrape and dab away the sand and grit lodged in the thick dollops of oil paint. He was not completely successful and to this day in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, you can see fragments of the landscape lodged into the seascape.

To Scheveningen

In the summer of 2022, I went to Scheveningen with my dad. It was Friday, July 16th, the height of summer. The day began with a trip to Mauritshuis in The Hague.

We saw Jan Steen’s The Life of Man, where a draped curtain is pulled aside like a veil to give us a peek into an inn. Oysters are shucked in the foreground. A child pats a kitten’s head with a spoon. The scene shows frivolity, flirting, disdain, disgust amongst a range of characters of all ages, and on the mezzanine above, a young boy playfully blows bubbles towards a skull. Jan Steen teaches us life is full of wonder, joy, despair, smooth, suggestive oysters and peeling, bitter lemons, but time goes on and life will burst like a bubble floating in a shaft of light.

As in my last essay, Jan Steen dished out lessons in his work. And like The Hague School’s attitude to the world around them, he was practical, unpretentious, not trying to hide any of the ugliness around us. We left the Mauritshuis and made our way towards the tram stop. We had a copy of W. G. Sebald’s Rings of Saturn with us. The book is a record of a journey made by the author through the coast of East Anglia, across the sea from Scheveningen. The narrator recalls a trip to Scheveningen in his past, where he lay on his back and dreams “for the first time in my life…and I was home.”[8] When he awakes on the beach, his mind departs the town, back towards his seemingly ceaseless pilgrimage of both body and mind.

On the tram, we passed the brackish swamps, the windmills, the sunlit udders of Friesian cows. We saw a massive, deserted theatre that was showing a pantomime performance of Aladdin. The tram veered past Madurodam. A miniature park of model replicas of famous Dutch landmarks and historical global cities with the promise of circumnavigating the globe with a smile. Dad remembered that as a kid he dreamt of going there. The shrunken world promises all visitors the chance to transform into a giant being and travel the entirety of the Netherlands in under one hour.

At the end of the tramline, it was eerily quiet for a summer evening. The bars along the promenade had seating for hundreds that were completely empty. The panorama has changed since Mesdag’s day: there was now a long wooden pier jutting out towards a Ferris wheel and a tower where bungee jumpers strapped in, ready to dive out over the waves.

We walked along the strand accompanied by gulls and finally found a place to sit. There were three bright blue sun beds, and we occupied two of them. Container ships dotted the horizon, two dimensional shapes of varying sizes.

The strong wind was blowing us off our blue sun-loungers as we read Sebald’s description of The Battle of Solebay. It was a naval battle in 1672 where the British Navy prevented an invasion of England by the Dutch republic, winning naval supremacy of the North Sea:

“At that date there can have been only a few cities on earth that numbered as many souls as were annihilated in sea battles of this kind. The agony that was endured and the enormity of the havoc wrought defeat our powers of comprehension, just as we cannot conceive the vastness of the effort that must have been required - from felling and preparing the timber, mining and smelting the ore, and forging the iron, to weaving and sewing the sailcloth - to build and equip vessels that were almost all predestined for destruction. For a brief time only, these curious creatures sailed the seas, moved by the winds that circle the earth…” [9]

We flicked to the pages where underlined sentences spoke about the planes above us, flying Icarus-like: “The aircraft at the tip of the trail was as invisible as the passengers inside,” and “the greater the distance, the clearer the view.”[10] We watched as tiny figures bungee jumped from the tower at the end of the pier, the shriek and yelp just making it to us over the wind and sea. The bodies were plummeting fast and then wriggling like caught herring in the Scheveningen air. We swam in the grim sea full of floating indistinct objects, sea kelp, debris and coastal sediment. It was cold.

In a chapter of Rings of Saturn, Sebald travels to Orford Ness, a deserted former nuclear testing site, a place of concrete returning to nature. Hares hopping and greenery erupting through the slabs of brutal grey. While there, he looked across the North Sea, towards Scheveningen, writing:

“As I was sitting on the breakwater waiting for the ferryman, the evening sun emerged from behind the clouds, bathing in its light the far-reaching arc of the seashore. The tide was advancing up the river, the water was shining like tinplate, and from the radio masts high above the marshes came an even, scarcely audible hum. The roofs and towers of Orford showed among the treetops, seeming so close that I could touch them. There, I thought, I was once at home. And then, through the growing dazzle of the light in my eyes, I suddenly saw, amidst the darkening colours, the sails of the long-vanished windmills turning heavily in the wind.”[11]

Fish guts in cube form

Hungry after our swim, we went to a kibbling stand. Two stern Dutch women were about to shut up shop. We were their last customers: they audibly sighed at our presence. I asked for two portions of kibbling and chips. Both women had peroxide-blonde hair, pushed back by the wind and, perhaps, hair gel. One of them bent down to get something from the freezer. Rising, she then slammed a great plank of a thing down onto the stainless-steel counter; several lemons bounced and rolled off due to the tremors. Vapour rose up as she peeled back the thick paper. Inside was an almost translucent block, and she began snapping smaller fragments off with her tanned hands. The cubes were clouded but as they slightly heated in her hands, within them we saw bones, red veins and chunks of white fish meat.

She dropped the cubes into a deep fat fryer, gave us tartar sauce and we paid. The modern fishing trade, with its fish guts in frozen block form, was not the authenticity we were chasing. She slammed the shutter down and we stepped out from the awning. To our horror every inch of the roof above was filled with gulls. We ran back under the awning as they began to hover. Through the thin material, we saw their shadows, beaks clacking, heads twisting, heard the impatient pattering of feet above our heads. In truth, the meal was awful, an unpleasant mush. We tossed the remnants in a bin and walked down the deserted promenade. Seagulls screeched behind us as a swarm surrounded the waste, ripping apart paper plates and remaining chips.

The scene was worthy of a page in Het Visboek.

We walked for a while down the empty promenade. The bars were soulless: derelict mausoleums to over-optimistic grubby commercialism. The beachland ballrooms of the past were decrepit, showing their age in their brickwork.

We made our way back to the tram. The town left a lasting impression on the both of us. We thought we would have told people of the great day by the seaside, the merriment, paddling in the shallows, the delicious fish, and the great scoops of ice cream. But, inspired by The Hague School, we were realistic. We asked each other on the tram, almost laughing, what on earth was going on there? Where was everybody? Did we just enter some kind of purgatory?

I am sure there are days when Scheveningen is the centre of the universe, but not when we were there. As a place, it felt like nowhere. The Hague School’s version of Scheveningen was another place from another time, never to return. Now, tourism has completely taken over; those early days of modernization and progress had mutated and seemed to have taken Scheveningen’s soul.

Writing or any form of art is preservation by documentation, memory in paint, retention in ink. Landscape paintings, like that of the Hague School, show the importance of documenting nature, realistically, probing themes of memory, identity, and humanity’s relationship with nature. Art is a voyage into an individual and collective past, highlighting the struggles with identity in an ever-changing landscape where evolution can become devolution, where progress mutates into destruction. My recollections of Scheveningen are not rose-tinted — far from it. As you have read, what appears to me now are visions — it is like I am wearing the cracked and bent spectacles of James Joyce recovered miraculously from the sand. There are scrapes crisscrossing the lenses, the thin wires are entangled, and there is grit stuck to the glass. Squinting back, I see spectres of ships and splayed rope, herring and fish bones, the departing courts of kings and chugging machines ploughing over the sand, digging into the marsh. Here, I have attempted to coil together the strands of my memories of Scheveningen on that day in July 2022 — to document realistically that single afternoon. As Georges Perec wrote:

“Space melts like sand running through one’s fingers. Time bears it away and leaves me only shapeless: To write to try meticulously to retain something, to cause something to survive; to wrest a few precise scraps from the void as it grows, to leave somewhere a furrow, a trace, a mark or a few signs.”[12]

The Hague School highlighted the importance of fishing to the economies and livelihoods of the coastal towns of the Netherlands — and its slow decline. Technology, innovation, new markets, greater appetites, more mouths to feed and a globalised economy have taken away Scheveningen’s industry. A ghostly presence haunts the landscapes and the lingering shadow of a bygone era emanates from paintings by van Gogh and The Hague School. The Herring King had lost his crown and slithered down to the deep, avoiding the nets.

Departing from Scheveningen

In the case of Scheveningen, we stared out on our loungers, drying off in the strong wind, the hums of planes passed over our heads. Our shadows cast before us on the sodden sand swayed with the distant bungee jumper, falling, flailing, floundering. As the dot moved downwards towards the sea, accelerating like the passage of time, in an instant, the chord pulled, then, they were hauled back into the Scheveningen air. We stood up, toweled the sand off our feet and left the strand behind us.

The Herring King had lost his crown and slithered down to the deep.

A couple of days later, dad was taking flight back home over the North Sea. While in the air, he flew over Scheveningen strand and sent a message with imagery. The description from a great height captures the pervasive feeling the town gave us. The long strand extends out into the horizon, as the water sloshes against the pier, a seascape forever stuck to us both, gnawing away like limpets.

“The greater the distance, the clearer the view” - from a great height the North Sea looked perfectly blue, and not a muddy brown infused with sea-kelp and plankton as it appeared up close when I swam there two days previously with my son. I thought of the three lonely blue sunbeds and wondered had the advancing tide washed them out to sea, dragged them to the depths, where they drifted to the seafloor like fantastical sea-creatures.

My last glimpse of the lowlands from the airplane window was of the thin ribbon of sand that is forever Scheveningen, and a vast wind farm in the North Sea. Shortly afterwards we were surrounded by clouds, and I could see nothing, until presently I beheld, far below us, the shadow of our own aircraft, a ghostly other. I drifted into a deep sleep, in which I found myself quite lost in a subterranean sea kingdom, although instead of swimming underwater, I was cycling on a very upright bicycle. I awoke with a jolt sometime later to see Dublin Bay, the safe harbour of Howth, and, above the village, my boyhood home was clearly visible.”

Footnotes

Photos by Charlie Jermyn and Gary Jermyn.

All other imagery taken from:

- https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/our-collection/

- https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/

- Het Visboek

- https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio/

[1] Franz Kafka, ‘Diversions or Proof that It’s Impossible to Live,’ The Complete Stories (New York: Schocken Books, 1971 [1988]), pp. 25-26.

[2] The preserved manuscript is now in the National Library (KB), close to Den Haag station. However, it is too fragile to be put on show. There is a digitized version.

[3] Cited in Richard W. Unger, Dutch Herring, Technology, and International Trade in the Seventeenth Century, 253

[4] Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday, 25

[5] Ibid.

[6] The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European, Stefan Zweig, p. 66

[7] Take a digital tour of the Panorama Mesdag: https://panorama-mesdag.nl/

[8] W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, p. 84

[9] Ibid, 78

[10] Ibid, 18, 19

[11] Ibid, 137

[12] Georges Perec, Species of Space, p. 91