essay

The mindless sc/troller

Blanka Gyulai

Blanka Gyulai is a student of Liberal Arts and Sciences based in Utrecht. She also brews beer and coffee on the side to sustain her expensive appetite for knowledge. During her 3-months internship at Het HEM, she explored topics at the intersection of technology, power, spirituality, and art. Originally from Hungary, she is interested in the division between Western and Eastern European forms of identity construction and the potential of art to be used as a tool to negotiate questions of (non)belonging.

mind

Check-in with... Maarten Spruyt

We sat down and looked back with Guest of Chapter 3HREE Maarten Spruyt, known for his work as a curator, art director and stylist, with an incredible knack for beauty and sensory perception. "I try to make exhibitions which make you look inwards, feel uncomfortable and sit with that for a moment."

Rustan Söderling

music

Singing To The Machine: Orpheu The Wizard

This mix by Orpheu The Wizard consists of a selection of songs loosely revolving around the themes of Mystics of the Chthulucene. First up in a new mix series, where artists, selectors, and music geeks connect sounds to a broader and recurring artistic research theme that weaves through The Couch.

essay

Are TikTok Healers Contemporary Quacks or Re-risen Witches*?

Are the countless self-proclaimed ‘healers’ giving medical advice on TikTok quacks? Or are they a sign that witches* have reclaimed their space in the health field, reviving lost knowledge and offering the care that mainstream healthcare still fails to provide?

essay

Mystics of the Chthulucene

Cthulhu – H.P. Lovecraft’s science fiction monster – lurks under the surface of the ocean as an elemental deity. We must wonder what lurks beneath the surface of the systems known as AI.

essay

POV:

Ginevra Petrozzi makes the case for a complicated relationship between ourselves and the artificial intelligence tools that guide us through our lives. The stories and myths we construct around the technologies we don’t understand can help us navigate the obscure and even violent power of artificial intelligence.

15

min read

A journey towards a new understanding about existing in the digital sphere

What is a pilgrimage? Why would people go on pilgrimages? Is a discussion around pilgrimages still relevant even in our Western, secularised society? What constitutes a postmodern, potentially digital pilgrimage?

These were questions that I, as a non-religious person educated within the Western framework, was posing to myself when I first encountered the topic of pilgrimages last year. For a museum studies course, I had to write an exhibition proposal for the Catharijneconvent, a museum of religious art in Utrecht, about the enduring significance of Medieval Pilgrimages. I found an entryway to the topic through the dominant institutional narratives on pilgrimages as guilt-driven journeys of self-transformation and cleansing. They seemed so distant, self-centered, something belonging to the history books.

How can we subvert that stereotype? How can the concept of the pilgrimage become a tool to help us cope with our present context, the Information Age? Can we ritualise the virtual and make online scrolling an open-ended journey?

Scrolling on my phone is me escaping from reality. A temporary disconnect from my surroundings. It helps ease the monotony of everyday life by transporting me to different places without having to travel; it allows me to turn off my mind for a second and allow myself to be submerged in the experience. But what do I do when it becomes too much, when my average daily screen time is 8 hours? When my desire to escape in the digital dominates my desire to exist in the world and experience it fully? Is there any way to reconfigure mindless scrolling as a form of pilgrimage, something temporary that I can derive meaning from, and from which I can return to my reality and live it without distraction?

This essay doesn’t give answers. It cannot give any. It asks questions and approaches them from certain angles which are far from exhaustive. It is an attempt to understand through opening up to ever-new ambiguities. It is itself a pilgrimage, a wandering of my thoughts, connecting to many other threads of experiences of other people from different historical times, contexts, and backgrounds.

Come join me on this mental journey.

Step 1 – Choose a destination aka. strip yourself away from mundane structures

Pilgrimages generally offer a way for the self to transform. The pilgrim undergoes a rite of passage both mentally and physically and experiences a change in their social role, returning different than when they left. Movement through space is a metaphor and a necessary tool for the mental transformation that accompanies it. (1) The journey offers a way for the believer to, through the effort that it takes to reach the site, mentally reorient themselves and cleanse themselves from negative feelings - of guilt, mourning, being lost or stuck in life, purposelessness – and reconnect with the transcendental.

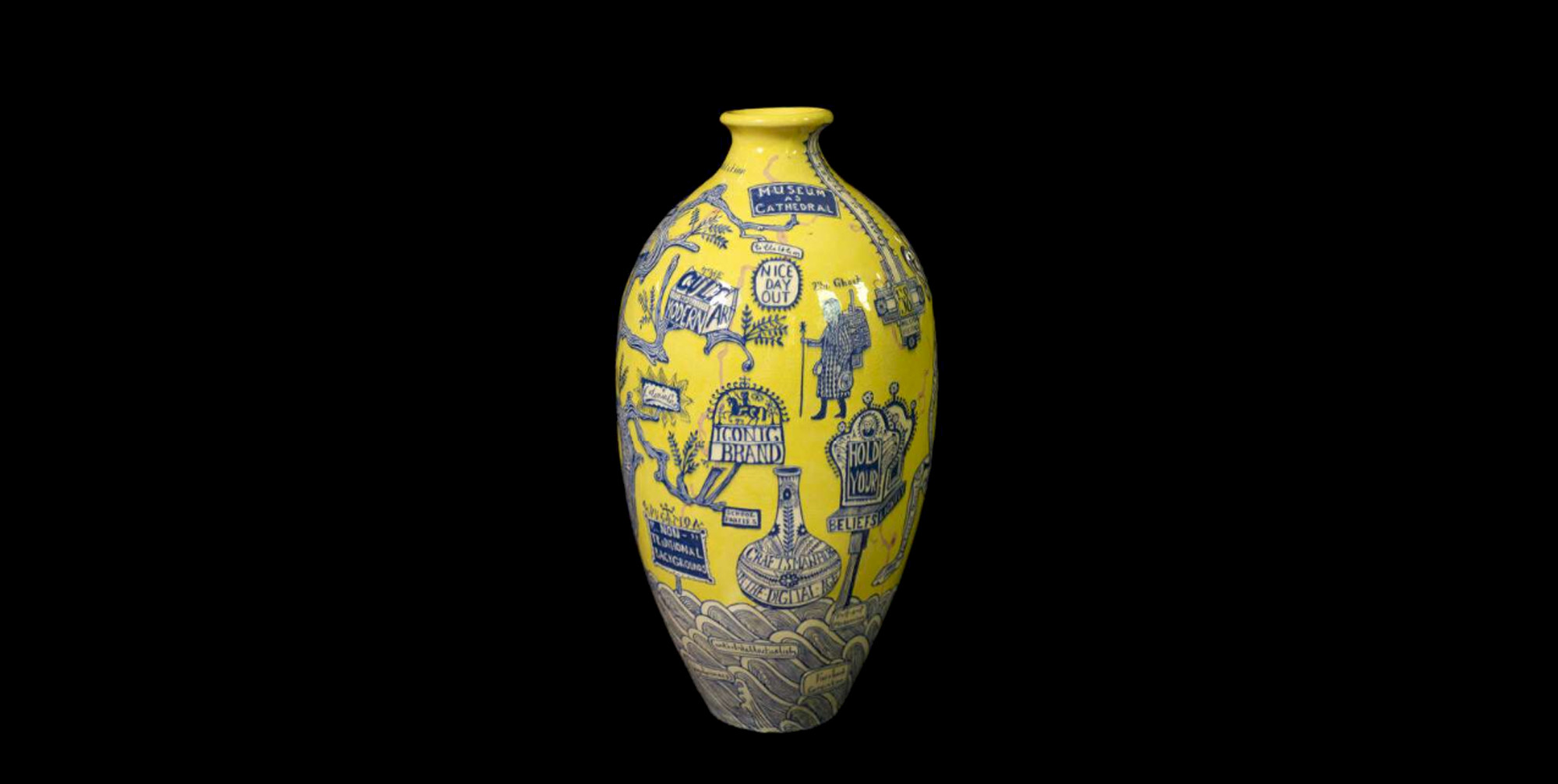

Since the Middle Ages, around 200,000 believers have undertaken the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela yearly. It is an enduring tradition in which people from all walks of life can take refuge and derive meaning time and again. The act of walking itself is of primal importance and is seen transforming the individual in three stages. The first part is for the body where the pilgrim is challenged physically. The second stage is the reflective stage, when the mind starts to wander. Thirdly, the soul is challenged, leading to the pilgrim reaching a deeper understanding of the goal of the journey. Travelers can choose from multiple routes spreading all over Europe to reach the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, and it is this free wandering of body and soul that creates meaningful experiences. At the destination, there is a set of rituals that need to be performed that gives a metaphysical significance to the physical effort that was necessary to reach the site. These practices mediate between the real and virtual, the virtual being something beyond the body that is attained through ritual and metaphorical transference.

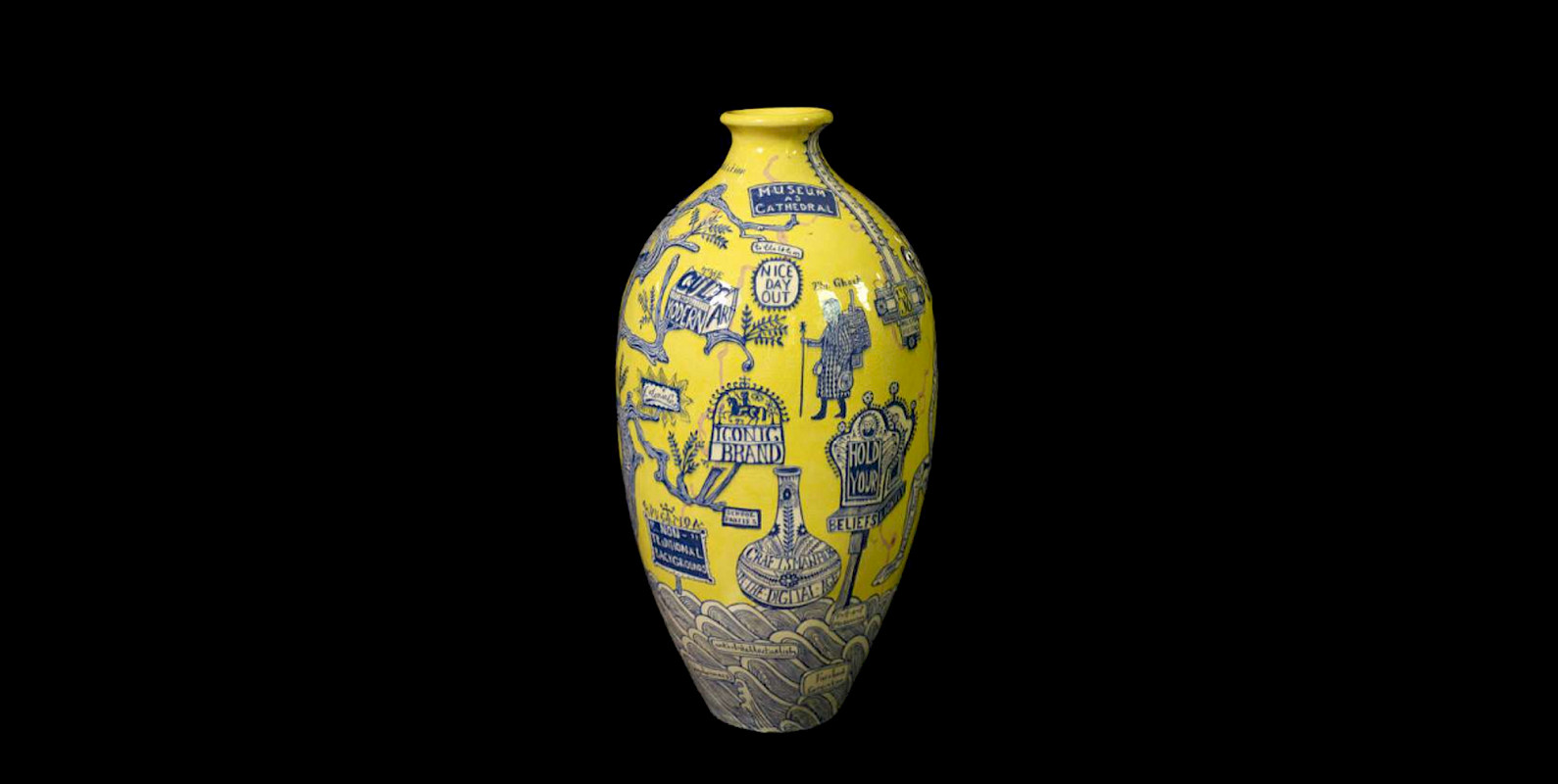

Though walking to Santiago de Compostela is traditionally a religious experience, it has become heavily influenced and decontextualized by the tourism industry. With the growing accessibility of visual representations of the pilgrimage through social media, people considering the pilgrimage can immediately find information about it through detailed accounts of other travellers and agencies promising to provide an expensive, all-inclusive experience that erases the ambulatory effort it’s supposed to take. The desire to escape the mundane, the everyday and find a true, authentic, and life-changing experience is heavily capitalised on.

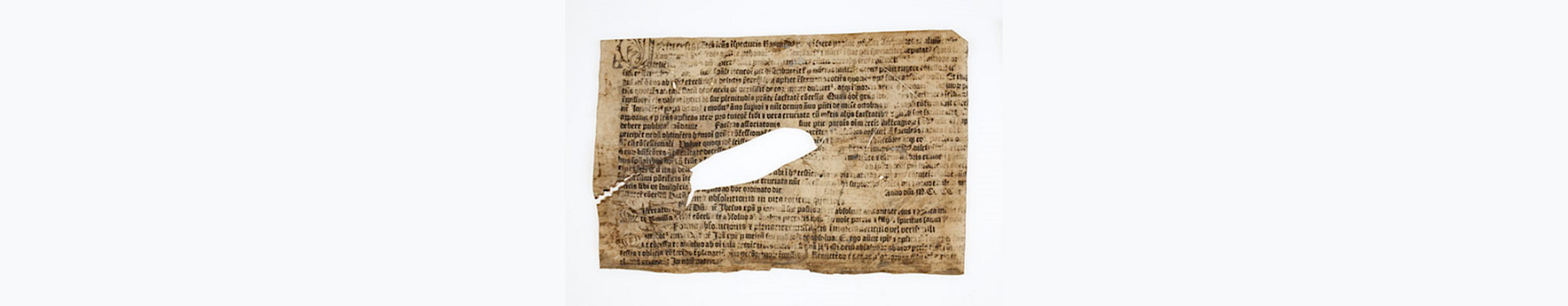

The commercialisation of religious experiences by institutional actors using the latest media technology is hardly new. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church sold indulgence letters that granted salvation to the believers if they also completed a pilgrimage or took part in the Crusades. The revenue generated by profiting off believers’ guilt helped to finance the Church’s empire-building activities and lavish lifestyles. The Crusaders providing manpower in the fight for the Holy Land was just an extra benefit.

But does a commercialized Santiago de Compostela hike even count as a pilgrimage? The enduring significance of pilgrimages is not that evident. (How) can we still derive meaning from the concept of pilgrimage, a term with considerable historical baggage connected to institutional religious power and capital?

Step 2: Go on the pilgrimage aka. allow your self to transform through its immersion in the experience

Pilgrimages, when supported by institutions acting on their own interests, have proven to be destructive (see: the Crusades). The millennial urge to escape and find refuge somewhere else is a self-centred one, not taking local contexts into account. Spiritual tourism is harmful and becomes a form of neocolonialism when it is centred around the singular self not being open to pluralist voices and contradictory experiences. (2) Reducing the spiritual succour that gains its meaning through tradition to an aestheticised experience posted on social media results in the presence of dominantly Western interpretations of the practices of non-Western and pre-modern societies online. Similarly to earlier Orientalist fantasies, the fascination with spiritualism reinforces stereotypes by looking at the practice through a Western/modern lens without understanding or providing a context.

But a pilgrimage, when understood more broadly, also offers something freer, something not necessarily religious that allows personal growth and reflection. It can express a “multitude of meanings for different groups of people.” If we acknowledge the value in its flaws, that it is “a dynamic process in which religious beliefs, political power structures, and economic endeavours are deeply intertwined and are the objects of change,” (3) we can subvert its meaning, and give it a second chance. Pilgrimages offer an ongoing process of negotiations between individuals about their lived experiences, giving way to alternative definitions of what constitutes meaning in life and dismantling generalising institutional narratives.

At its core, the pilgrimage is about attributing meaning to something (an idea, a memory, an emotion, connected to a place, an object, or an image) by spending time on it through taking a journey, or just freely dwelling around it. Pilgrimages are still present in contemporary society, and they are highly personalized. In a time of increasing uncertainty about our shared futures, such embodied ways of being and devoting attention can help make sense of our place in the world in relation to other forms of existence.

This way of looking at travel is reminiscent of the attitude of the Baudelairian flâneur, an artist archetype tied to the urban architecture of early modern Industrialism. Charles Baudelaire, in his 1863 essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, describes the flâneur as the ideal ‘modern man’, one whose constitution is suited to taking in the world as it is, with the curiosity of a child, freely strolling around the city without any preconceived expectations of it. (4)

The term became popularised in academic circles by Walter Benjamin, who characterised modernity as a sensory overload from dizzying urbanism. In his understanding, the city has a dualistic effect on people: it negatively induces alienation and, to the stroller who embraces the freedom and mobility of it, intoxicates the receiver with all its sensory richness. (5) Thus, being a flâneur is both a mindset and a transformative experience, and its practitioners share both the pilgrim’s and the tourist’s fascination with not simply the destination but travel itself, and the desire to experience something new and authentic.

In his essay ‘Modernity, Hyperstimulus, and the Rise of Popular Sensationalism’, Ben Singer argues that this way of framing modernity as frenzied, fragmented, and disorienting induced by the traffic, noise, signs, and billboards “anticipates much of what contemporary theorists have described as the condition of postmodernity.” (6) The intensification of nervous stimulation is not only present in popular imaginations of the city but, with the emergence of digital technologies, also on our screens. The proliferation of both visual representations and different user interfaces creates a disorganised experience, where one is constantly bombarded with a myriad of information, while also being encouraged to perform multiple identities adapting to the structure of each site.

This made me wonder:

Is our existence in digital environments in the Information Age is comparable to the experience of the 20th-century city dweller? If the postmodern (digital) experience is a similarly disorienting experience to that of the modern flâneur, then is it possible to adopt the same approach to the web as to the city, where the mind can freely wander and transform, allowing the individual to come out of it differently? What happens if we consider online scrolling as an open-ended journey that shapes our experience of it?

I want to approach online scrolling on the Internet through the framework of traditional pilgrimages, to play with the question of what pilgrimages can mean in our society.

Can we go beyond the wonder and amazement over new technologies that characterize the approach of the flâneurand acknowledge the institutional oppressions that contributed to making these advances possible? Can postmodern pilgrimage become a conscious tool of introspection rather than a signifier of religious devotion?

Creating something meaningful out of something oppressive and deeply flawed resonates with both the experience of people embarking on the violent Crusades for money in the Middle Ages and people trying to find their way in the new possibilities and dangers the Information Age can offer.

Step 3: Come home and reflect aka. reintegrate this transformed self into the mundane structures it stripped itself away from in the first place

In most debates about the efficacy of virtual pilgrimage, that is reaching the virtual representation of a famous pilgrimage site through our browsers, as opposed to physical ones, the main argument is that it lacks an aura. However, it is not really the physical presence of a site but the story or mythos around the place that gives it its perceived transformative power, which can be mediated in multiple ways.

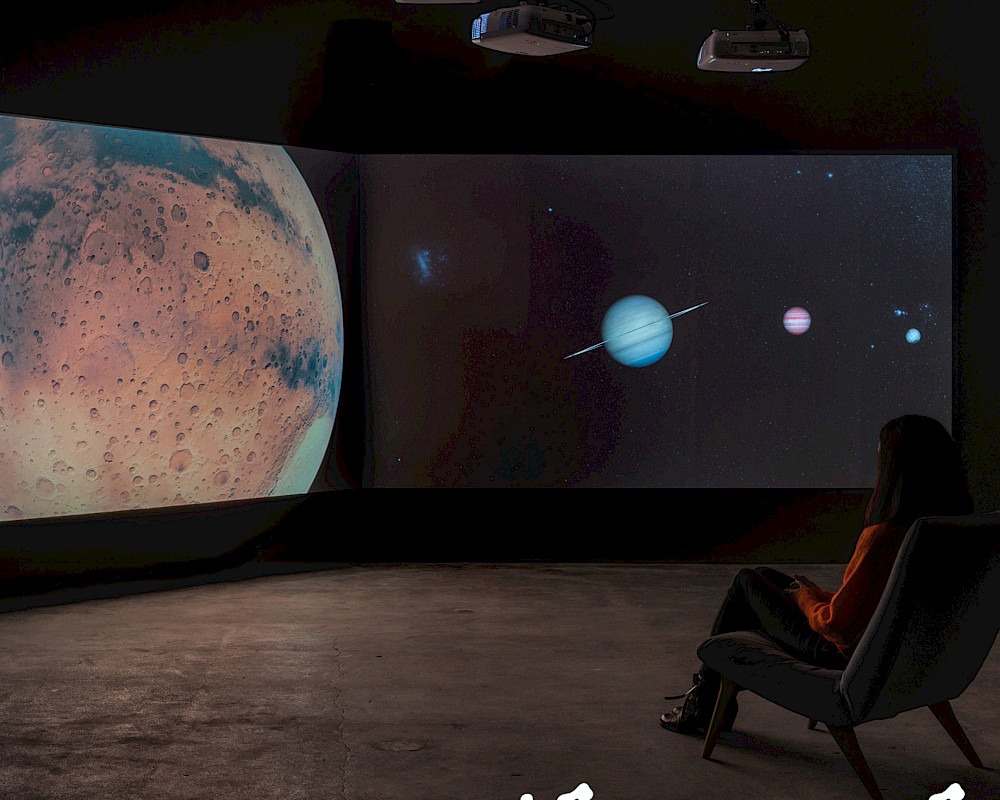

A physical pilgrimage is already “a ritualised, hyper-meaningful journey both inward and outward – to a person’s or group’s sacred centre, set apart from everyday life, and built on rich mythological representations and symbolic markers.” (7) The importance placed on a specific physical location is an allegory or, using more of a technological language, a hypertext that prepares the mind for a mental transformation. From this view, pilgrimages done within the digital realm can embody the same amount of agency as physical. As Allison Williams writes: “‘Virtual reality’ is not new but has been a part of the metaphors used within Christianity for centuries.” (8) Christ could be experienced through the bread and wine of the Eucharist and in Medieval Europe stone labyrinths could substitute a journey to Jerusalem when it was impossible to go there in person during the Crusades. These early instances show that it is the mental journey that matters; coming up with a virtual intermediary that facilitates a connection could provide equal opportunities both in terms of spiritual and earthly rewards as the equivalent direct experience. In this line of thought, pilgrimage can be undertaken mentally since the physicality of the site becomes substituted virtually through signs. Wandering then is still possible but in the realm of the virtual.

I already argued that pilgrimages are spiritual experiences though their value can be undermined by institutional actors. They can both be undertaken in the physical world or aided by the virtual. But how can the spiritual be virtual and the virtual spiritual – in other words, can digital pilgrimages become meaningful and subversive?

Technology itself also always had a religious character. It is present in the way new technologies have been anticipated and sanctified for their potential to change society for the better through the transmission of topoi (9), or the way we trust algorithms to make predictions and influence our futures even without knowing how they exactly work. (10)

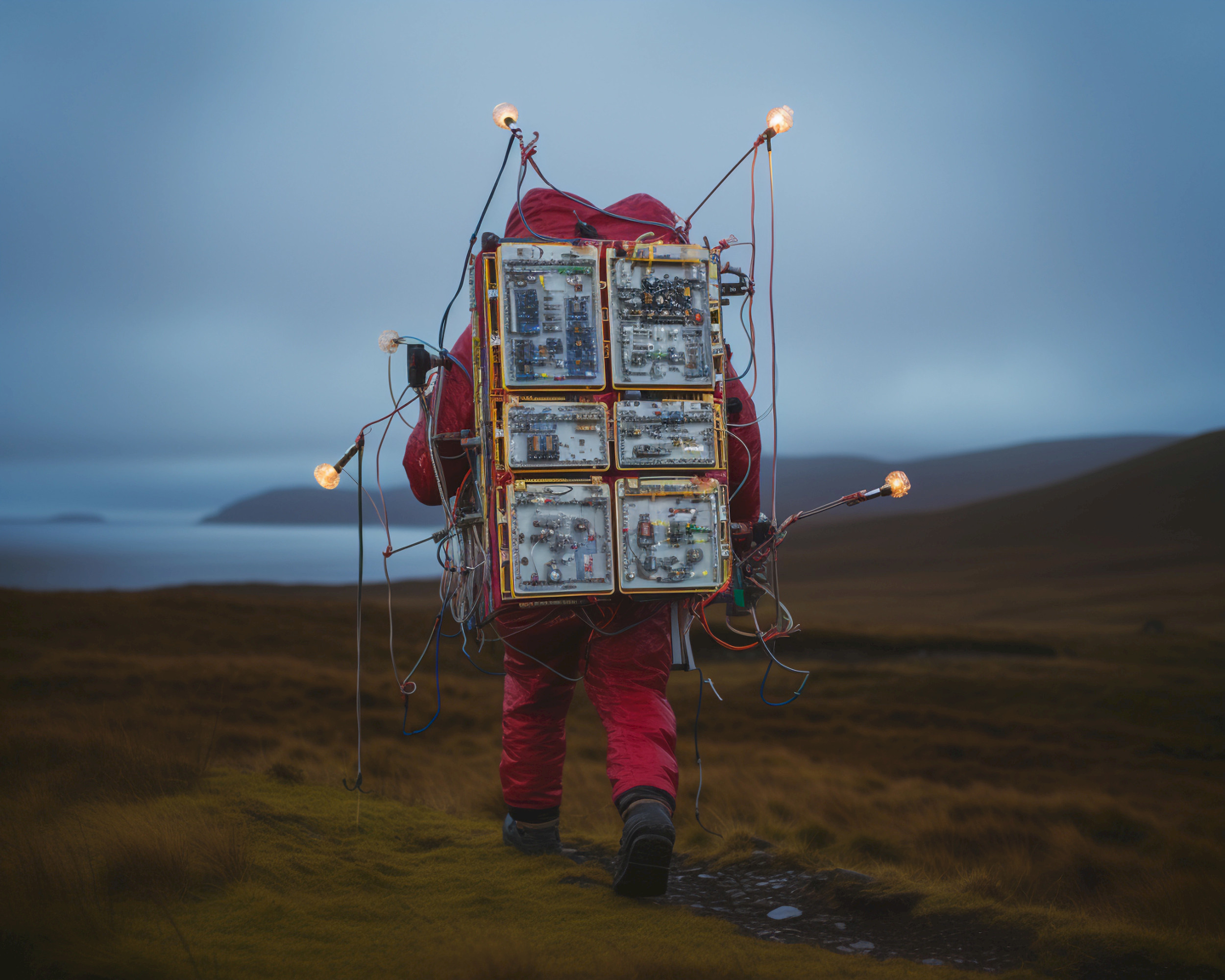

The term transhumanism explains the postmodern preoccupation with technological progress to improve one’s life and overcome human limitations in terms of strength, intelligence, or health. In this view, the individual can reach something that is closer to the transcendental with the help of technology, through constant betterment a stage is reached where one can become one with the divine. As a reaction to transhumanist thought, posthumanism is concerned with what comes after this initial stage, what happens when people reach the divine, themselves become a hybrid between human and God, cyborgs. (11) The posthuman is something beyond the body, as a rational mind, it can take any shape and any form in cyberspace. (12)

Posthumanism then proposes that technology can be a realisation of metaphysical and spiritual endeavours, just as pilgrimages were to sacred sites in the Middle Ages, but not being tied to any physical body or space. In this line of thought, “ritualising the virtual’ is crucial (13). We need to come up with strategies to make a place for pilgrimages within the digital.

Digital pilgrimage then, used more broadly than just to characterize religion practiced online, can go beyond itself to illustrate the spiritual attitudes people adopt towards the web, and technology in general. I believe the term could be helpful when talking about this approach of scrolling and stumbling upon, exploring, and transforming our understanding of the world and ourselves. It can serve as a framework to explain the quality of the Internet that enables users to freely wander in the online space and navigate between different potential identities in their search for meaning and belonging. Allowing yourself to bring the mentality and special experience of the pilgrimage into the digital can bring the succour (soul healing) of religion without the institutional baggage.

I believe digital pilgrimage can become a form of data healing as envisioned by the feminist tech scholar Neema Githere in her Data Healing Recovery Clinicas. She wrote in her Manifesto that Data Healing "emerged (…) to draw links between technology, nature, and spirituality. Our integrative approach centers on indigenous wisdom and its perspectives on wellness and interdependence. Here at the DHRC, data is used to empower, not categorise.” (14) It is a collaborative and experimental practice looking for alternative ways of healing rooted in Indigenous practices to cure the traumatic and harmful experiences amplified by the Web. I believe that by rethinking what pilgrimages are to people, by stripping the definition away from the institutional and commercialised Western overinterpretations and returning to its original sense, we can come to a new understanding of our online experiences as well.

Below, as a parting note, I envision one way in which we can try to practice a digital pilgrimage more constructively.

RITUALISING THE VIRTUAL: A game to subvert the dominant definition of pilgrimage into a practice of healing and recognition.

-Open a browser.

-Close all your tabs.

-Play Wikipedia ‘rabbit hole’ with a friend for 30 minutes. Always let your momentary interests and impulses guide you as you go deeper and deeper into the web.

-Did you reach something completely out of place and surreal? Good. Remember it well!

-Close your computer.

-For the next 30 minutes engage in a completely different activity outside of the digital realm. Go walk your dog, knit, make yourself a meal. But don’t look at your phone!

-Now return to your computer. Try to retrace the route you took previously. Mentally try to note every turn and decision you made that led you to that completely crazy outcome. Was it meant to be?

1. Turner, V. & Turner, E. (1978). Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press.

2. Future Artefacts Podcast (October 2021). Rebeca Romero: The New Worshipers (El Peregrinaje).

3. Luig, U. (2018). Approaching the Sacred: Pilgrimage in historical and intercultural perspective. Berlin: Edition Topoi.

4. Baudelaire, C. (1964). The Painter of Modern Life. New York: Da Capo Press. Originally published, in French, in Le Figaro, 1863.

5. Seal, B (2013) Baudelaire, Benjamin and the Birth of the Flâneur. In Psychogeographic Review. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

6. Singer, B., ‘Modernity, Hyperstimulus, and the Rise of Popular Sensationalism’, in Charney L. & Schwartz V. R. (eds.), Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life (Berkley: the University of California Press, 1995), pp. 73-75.

7. Di Giovine, M.A., Elsner, J. (2016). Pilgrimage tourism. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham.

8. Williams, A. (2013) Surfing therapeutic landscapes: Exploring cyberpilgrimage, Culture and Religion, 14:1, 78-93, DOI: 10.1080/14755610.2012.756407

9. Huhtamo, E., ‘Dismantling the Fairy Engine: Media Archaeology as Topos Study’, in: Huhtamo, E. & Parikka, J., Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications (University of California Press, 2011).

10. Petrozzi, G. (2023) ‘POV’ on The Couch, accessed 16 August 2023.

11. Graham, E. (1999). CYBORGS OR GODDESSES? Becoming divine in a cyberfeminist age. Information, Communication Society, 2(4), 419–438.

12. Lister, M., Dovey, J., Giddings, S., Grant, I, Kelly, K. (2003). "The everyday posthuman: new media and identity." In New Media: a critical introduction, Taylor & Francis, pp.282.

14. Graham, 1999. Manifesto of The Data Healing Recovery Clinic: A feminist tech vision by Neema Githere.