essay

Ghosthood and the Uncomfortable Familiarity of Haunting

Milo Sharafeddine

Milo is a Lebanese visual artist and writer based in The Hague. Their work is often inspired by the instability of personhood, place and its social meaning, ghosts and haunted symbolism, and technology—specifically digital imagery and recording, internet-age media, and their alternative histories.

essay

Productively Unproductive

Arne Willée rescues idleness from its morally dubious past and presents it as a needed, critical resource.

video

Air

Nonlinearity is not just a collision of times, but an indifference to time

essay

Escape From the Internet

“Remember when on the internet no one knew you were a dog?"

poetry

The horizon shifts as I do

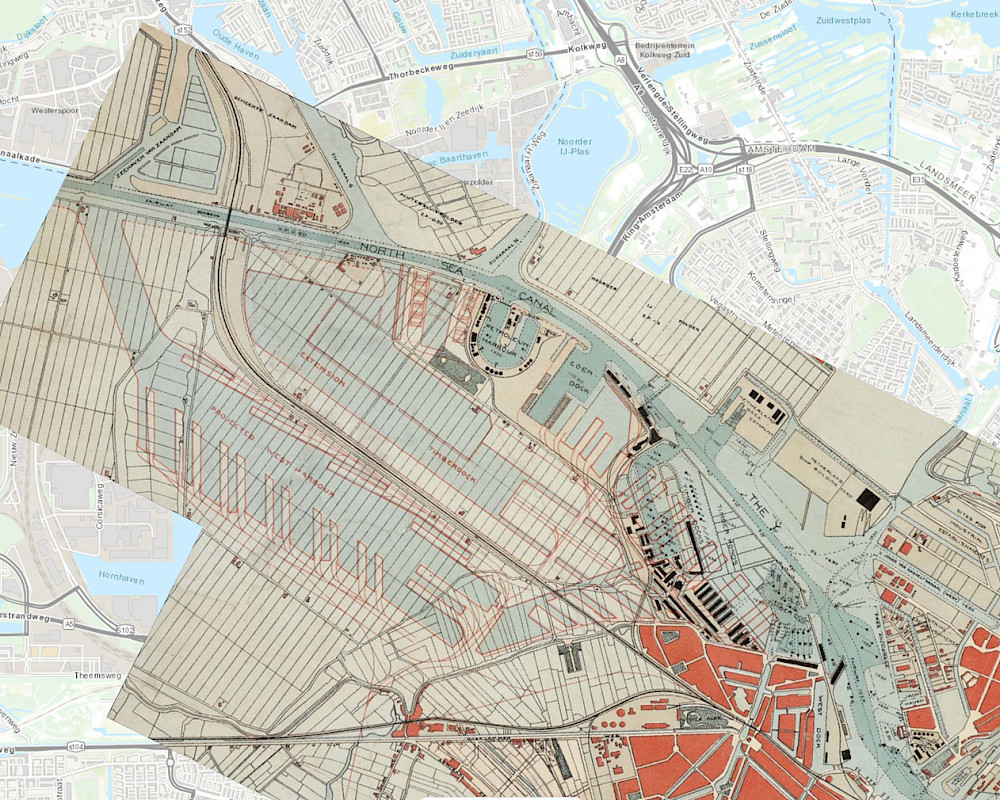

Did you know that sequoia trees can grow taller than data centres can?

In the outskirts of Amsterdam, there are many of the latter, corrupting the horizon.

25

min read

Chapter 1: The Horror of Personhood / The Birth of Ghosthood

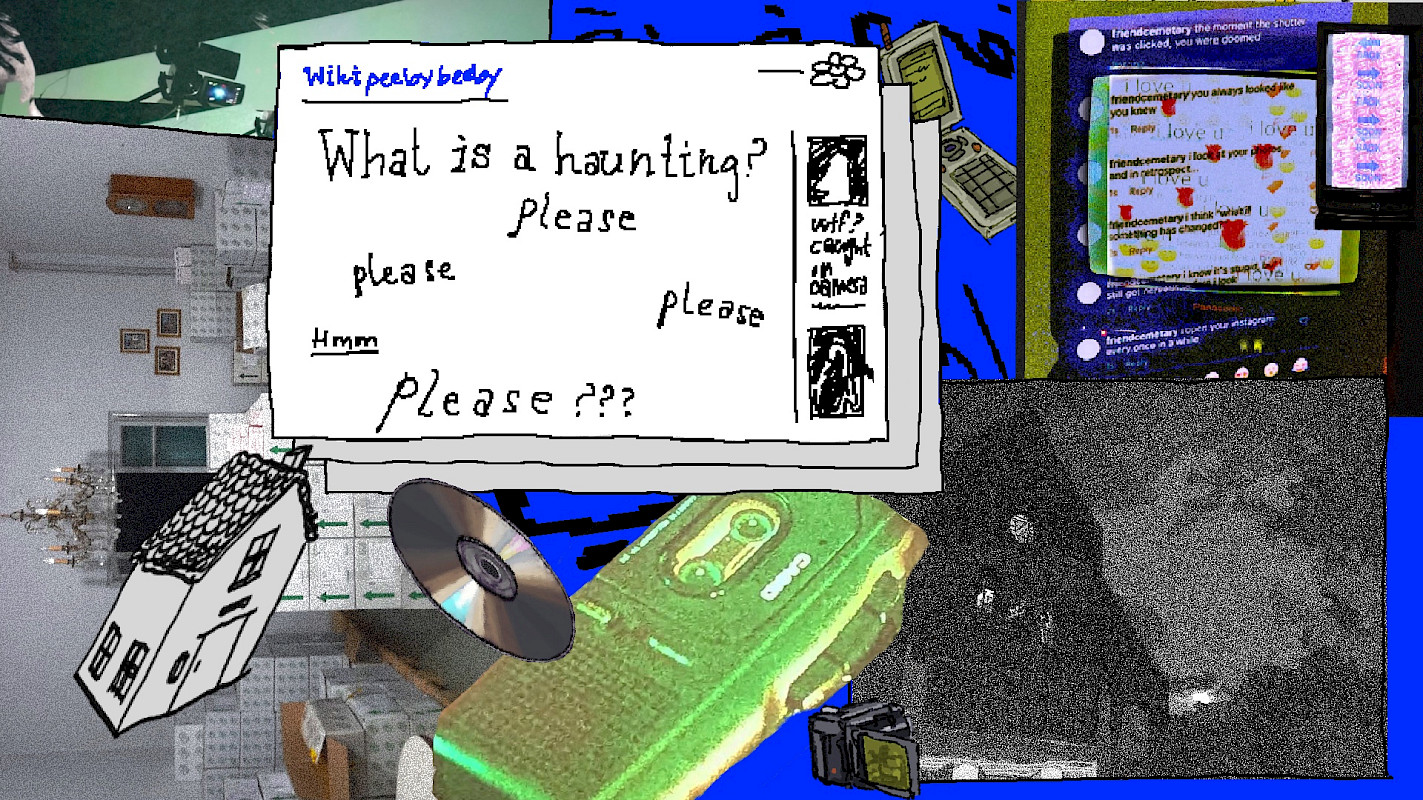

To be haunted is to be full of ghosts. Mainstream cultural and spiritual understandings of ghosts usually refer to the lingering and present soul of a person who has died, and that understanding is usually symbolized or embodied by an invisible, humanlike figure. The body of the deceased, but removed from its lively, fleshy shell, a stubborn, dichotomous belief (dead/alive, body/spirit), and a symptom of mainstream western thought. However, the 1990s sent the world into a cultural shift, one that would silently embed itself into every corner of popular culture, political discourse, and literary analysis. This shift came to be known as the “Spectral Turn”, inspired by Jacques Derrida’s 1993 book, The Spectre of Marx. Though situated in an economic and political field, The Spectre of Marx pushed Derrida’s deconstructive philosophies into wider discourse, and with it a new term that he coined: Hauntology–a play on the words “ontology” and “haunting”. Contemporary representations have seen the ghost deconstructed into a philosophical, historical, political, scientific, and technological concept. The absence of a solid definition for the ghost is core to its existence— to understand ghosts is to admit uncertainty in that very understanding. “Its own status as discourse or epistemology is never stable, as the ghost also questions the formation of knowledge itself and specifically invokes what is placed outside it” (1). This elusiveness is at the heart of my interest in ghosts, and the notion of haunting; the same elusiveness I associate with feelings and experiences I can’t explain, that make people turn to science, spirituality, or superstition. If a ghost can be understood in this deconstructed manner, then how does it haunt, and what does it mean for a place to be haunted, or an object, or an artwork?

What drew me to the tangible absence of the ghost was my own elusive and ill-fitting identity. I wanted so badly to escape the horror of being known, the discomfort of being seen, and the pressures of personhood. I needed a reverse-exorcism, to achieve a personhood that has been saturated with ghosts. Thus, the birth of “ghosthood”, a name for my holy grail– the quality of being a ghost. Following this introspection, I made a resolution: to reject internally the dichotomies (body and self, past and present, known and unknown) and the rigid rules of personhood; to embrace transformation, fluidity, and ephemerality. A pilgrimage to ghosthood, and a path that is as much one of uncertainty, discomfort, and violent rejection as it is one of indifference, release, and tranquility.

Through this reflection, I begin to question the composition of ghosthood. How would I deconstruct the fluid nature of the ghost into qualities that, when identified, would mark the self as a ghostly self? To start, I posit fluidity as disregard for limitations and absolutes, and the acceptance of change and open-endedness (never one side of the coin, but somehow the flipping, shifting thing of it).

Admittedly, it’s difficult to perceive the self as something detached from any meaning. I have at many moments of my life felt stained by something I’ve experienced, somewhere I’ve been, or someone I’ve known. Instead, the ghostly self is polluted with a multitude of meanings, carrying a layered abundance of experiences and associations (now you tell me I remind you of a friend, but one that you can't seem to name).

Transformativeness lends a directionality to pollution; if pollution is to be understood as a layering, then transformativeness is the movement of these layers. It is the constant rearranging of fragments into new and different configurations (2). The two qualities work together to create a ghostly self that is perpetually metamorphosing, but that retains its core. It does not completely evaporate all ties to (bodily, cultural, or social) structure, but rather sees them as instances of grounding– landmarks, rather than tethers (I ornament my presence with souvenirs from my prior incarnations, but they have no weight on me).

The ability to live with one’s ghosts, that is, to embrace one’s fluid and multitudinous nature, implies foregoing linearity or chronology in understanding the self. Consequently, this allows a nonlinear understanding of the world– and with it, the ability to see ghosts in everything. The ghostly self recognizes that just as the self exists in fleeting instances, so does time; time, like the self, falters and shifts. Time, according to Derrida, is a play of traces (3). It is through nonlinear understanding that other possible worlds are unearthed, existing outside the margins of the linear passage of time (they move within the overlapping folds of time; real time: the looping, skipping, fluid thing).

Finally, ghosts are mute heralds: omissive, not in the sense of committing this erasure, but of emphasizing the presence of absence, of a counter-narrative which exists between the lines. In this way, the ghost is a signifier, but whose signified isn’t necessarily fixed (they live in the subtext, dodge the dots and crosses; they allow room for contradiction).

These qualities provide a framework to understand what it is to be a ghost, and to identify ghosthood not only within identity, but also objects, media, concepts, or experiences.

Chapter Two: Haunting, Discomfort, and Familiarity in Technology and Place

I define ghosthood as an ontology (4) that is fluid, and in this fluidity exhibits polluted, transformative, nonlinear, and omissive qualities. Launching from this definition, what, then, is haunting? After all, “the ghost is just the sign, or the empirical evidence if you like, that tells you a haunting is taking place.” (5). If haunting is the primary role of the ghost, then we can understand ghosthood as a haunted personhood, and the act of haunting as the emphasis of the ghostly qualities in a subject. However, to sit and analyze whether a subject exhibits these qualities requires a level of detachment, and haunting may be a more slippery phenomenon to understand experientially. This is where I arrive at the questions: How do I identify a haunting, if I don’t want to delve into its internal machinery? What is the aesthetic of haunting, and its outward effect? I decided to use two case studies that exhibit qualities I find difficult to explain, and that to me feel very haunted, such that I can better understand them, and in doing so, better understand haunting. These two case studies are technology and place (6).

Why do technology and place feel haunted to me? Perhaps it is the way that they visibly mark the passage of time, or that they’re all around us, all the time. One can argue that this can be said about other things (nature, art, fashion, vehicles... anything that reflects its era, anything that can wither), and to that I would say: yes, and those things are very haunted in their own right. I suppose it is just a matter of romance and sentimentality that I choose to explore technology and place– they feel personal, and beautiful, and tragic, and inexplicable, and I think these qualities are just as present in ghosthood as their previously mentioned counterparts. They’re just infinitely more difficult to dissect.

Technology is a deeply haunted field. In its ability to preserve the past such that it lives on in the present and future, it is non-linear, and can be said to produce ghosts. In its tendency to reflect, aesthetically and functionally, the styles and limits of its time, it is evolutionary and transformative, but still highly referential. In its attempts to become more invisible, more relatable, and in seeping into every corner of our world, it is fluid, both in shape and in nature. Throughout history, breakthrough technologies like the radio, the camera, the X-ray, and others, have sparked discourse about ghosts and mortality. This happened for a multitude of reasons, from those who instantly wished to use these technologies to glimpse or communicate with the dead, to those who feared that these disembodied recordings were slowly consuming their souls, to those who found that what these recordings were really doing was immortalizing their users. Tom Gunning refers to this digital reproduction as “the mechanical reproduction of the image gone wild, with each person (to quote André Breton’s marveling description of the climax of a silent American serial) ‘followed by himself, and by himself, and by himself, and by himself’.” (7) There is an interesting contradiction at play between the replicated digital self, recorded whether in voice or image, forever frozen in time, and the decaying of this digital self, evident within the crackle of old records, the weathering of a photograph, or the poor quality of the digital images of our childhood. This unequal temporality gives way to an uncomfortable meeting of familiar and distant, one that draws us in with recognition but keeps us away by making apparent its own absence.

To say that a place is haunted is high praise. To ascribe ghosts to a space is to give it “social meaning and thereby make it a place” (8). Ghosts imply social meaning due to their connection to memory. Collective memory– such as memories of war, of victory or loss, historically impactful and large in scale– can often leave prints on a place, from physical, visible marks, such as bullet holes, sculptures, and architectural interventions, to more invisible ones, such as changes in demographic, or an increase in surveillance, a feeling of ease or unease. However, smaller scale or even individual memory also leaves marks on a place. In cities where people grew up, met friends and family, played, commuted, and lived their lives, it is possible to feel the remnants of those memories. But place is inseparable from time; places that we have grown up with age, transform, and die, and in that, they become heralds for the infallibility of death. In experiencing a place that has undergone transformation, such as a childhood home that has changed ownership, or a war-era building that has been repurposed, we experience a layering of moments in space and time, carrying with them the memories of each of these layers. They imply that we are never only in one place at a time, but in a multitude of different places, as a multitude of different versions of ourselves, happening all at once, feigning the appearance of progression. The result is a homesickness tied to the feeling of being “homeless in time” (9), the feeling that this place no longer feels ours. Transformed places that we know are heavy with the feeling of something missing– their entire identity becomes the thing that they are not, and can feel uncanny in their uncomfortable mashing of familiarity and unfamiliarity.

If places can age and die, they can also be murdered. If transformed places are uncanny, then this is epitomized in contemporary, neoliberal urban design. The “optimized city” that has spread like rot over the places we have grown. It is unspecific, streamlined, and muted lest we feel inclined to loiter and become distracted from our tasks. It is a method of suppressing personal and collective identity in favor of a globalized and capitalist (and frankly, boring) non-place. But a place can be a ghost, too. It haunts, in whispers of before that have survived in forgotten corners of the city, in its own felt absence, in little acts of rebellion (I think of graffiti, of hanging out in parking lots, of video games and movies that place literal ghosts in the creepy, liminal emptiness of the global city and its failed landmarks). A place, once haunted, cannot be truly destroyed. Surpassing its built form, place is an amalgamation of memories, stories, energies in the air.

“The house, like man, can become a skeleton.

A superstition is enough to kill it. Then it is terrible.” (10)

Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea (1866)

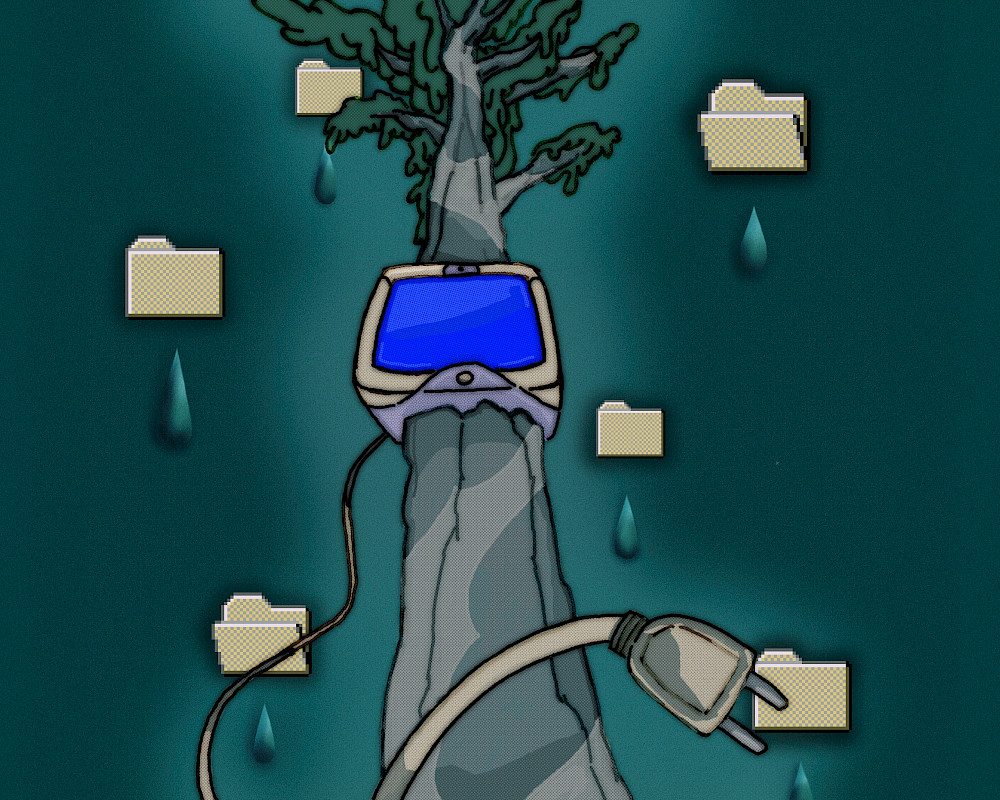

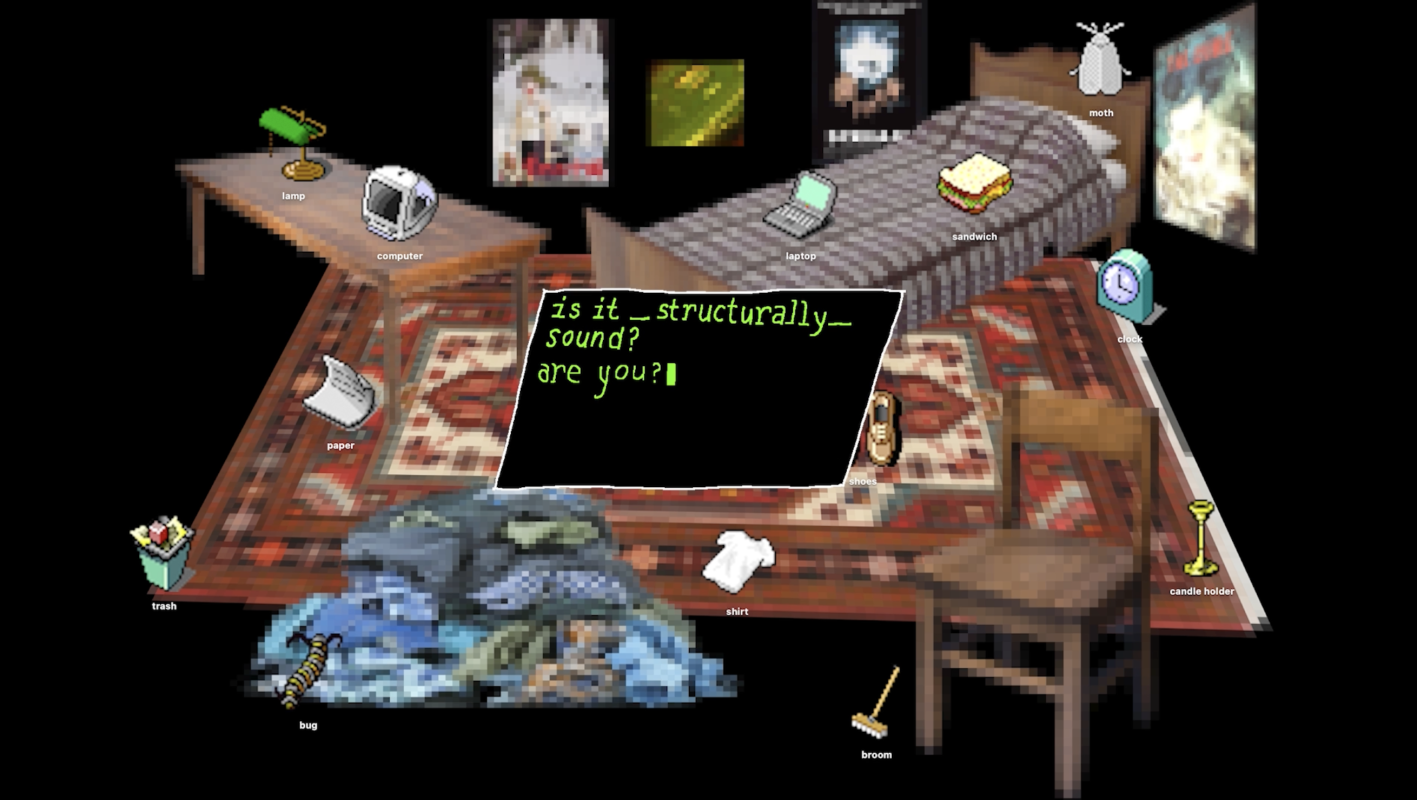

Considering their individual qualities, it’s interesting to see the junctions at which technology and place intersect. One of those intersections is virtual space (11). Something that gives virtual space hauntability is the way that it interacts with the physical barrier of the human body. For the user, a television or computer screen serves as a fourth wall. When a user is immersed in virtual space, the fourth wall could be said to be intact, meaning that the user is forgetting (or ignoring), to a certain degree, that they are a physical body outside the virtual realm. However, due to technological limitations, that physical barrier still exists, and with it, cracks in the otherwise intact fourth wall. The oscillation between physical and virtual body/place creates a dislodging effect, placing the user on a nonlinear positioning. The barrier is transformative, it blurs at times and sharpens at times, but it is always there, keeping the user aware of their physical self polluting the virtual environment, and turning the experience of self into a fluid one.

Does that mean that the user is haunting the virtual space? This is where the distinction between looser and more literal interpretations of virtual space comes in. A chatroom is any platform on which users can communicate through text messages, audio, or video. In most cases, the chatroom does not take the shape of an actual room, but is referred to as a chatroom due to the implication that it is a meeting spot for users. Thus, the ‘place’ aspect of the chatroom is implicit, and the interaction of the users is what forms its structure. In this case, the place, which is cyberspace, is what takes on the role of the ghost. However, in a literal interactive virtual space such as VR or video game maps, place is explicit; the digital physical environment forms the structure of the space, and the user is only a projection, either embodying a simulated being (an avatar), or implied through first-person perspective. In this case, the user takes on the role of the ghost. It is apparent that the haunting does not hinge on the dichotomy of real and virtual, but on the spectrum of implicit to explicit, emphasizing omission.

I remember certain video game environments the way I remember houses I grew up in. Most of the time, I would be watching as my sister played, entering creepy cabins filled with deadly monsters, and even though she knew she was in no real danger, she would proceed with caution, and even though I wasn’t even the one playing, I would feel threatened, frightened, as though at any moment, I may find myself there. Some new games have almost lifelike graphics, impressive ambient scores, and haptic responses that make it easy to lose yourself. But even seeing low-poly architecture with low-poly monsters on a boxy TV screen (with music playing harshly through cheap speakers) had us forgetting ourselves. You wouldn’t be able to convince me, then or now, that those weren’t real places.

Chapter Three: The Aesthetic of Haunting

Through this glance at technology and place, I arrive at a possible answer to my question about identifying a haunting: that experiencing a haunting challenges the stability of our positioning in time and space, triggering feelings on the spectrums of comfort - discomfort and familiarity - nonfamiliarity.

Memory, as we’ve explored, can be nostalgic and comfortable, but it can also be traumatic and uncomfortable, such as the image of something we wish we hadn’t seen, or the phantom touch of something we wish we hadn’t experienced. Time, inextricably linked to memory, can evoke similar feelings. The nonlinearity of time means that we are constantly walking in and out of bubbles of time (12)– we get lost in a daydream of a pleasant future, or we find ourselves in a sudden panic about a bad future. Walking into a bubble of other-time can mean being suddenly visited by an intrusive bad memory, or a welcome good one, or the disorienting vertigo of deja vu. In this way, familiarity (which is born of memory) can be utilized to create a sense of either comfort or discomfort, and this tool can be used in parallel with a nonlinear experience of time to inspire an atmosphere of haunting.

A case study which illustrates this haunted quality is the website foundphotos.net, which hosts a filtered archive of thousands of images publicly shared on the internet via peer-to-peer file sharing networks. Due to the range of image sources, the photos are often amateur, intimate, and domestic. In an interview with Pro Photography magazine, Found Photos creator Rich Vogel stated that the photos “showed something interesting or human, and made you feel like you’re connecting with people and their lives.” (13). It is undeniable that there is an element of familiarity that accompanies candid and intimate photos of strange people and places.

When we look at photos like this, we project onto them our own memories and biases. I can see myself in a photo of teenagers making silly faces with their friends, see houses I’ve known in photos of messy living rooms. But there’s a barrier there, where the suspension of disbelief falters, keeping me from fully connecting with them. As though I’m suddenly reminded that these are not my memories, not my friends, not my house, and I feel a little disappointed...maybe even betrayed.

On Found Photos, Mark Fisher says, “It is precisely the decontextualized quality of these images, the fact that there is a discrepancy between the importance that the people in the photographs place upon what is happening and its complete irrelevance to us, which produces a charge that can be quietly overwhelming.” (14). Time also creates a rift between the photos and their viewers. Found Photos was founded in 2004, and as such the photo quality is reminiscent of a certain time: high-key flash creating a lot of contrast, red eyes, oily faces, or on the other hand, blurry photos in low-lighting, with an orangey-redness that we can’t quite get rid of. This dates the photograph, and positions it in a specific decade, thus making us ultra-aware of our own positioning in the present, and furthers the dissonance in our viewing experience.

Chapter Four: Haunting as an Artistic Methodology

The notion of using time and memory as tools to create a haunted atmosphere led to further curiosity about creating an artistic methodology that is haunted, or produces haunted works. However, to suggest a guided or restrictive set of rules as a ghostly methodology feels like betraying the very essence of ghosthood. Just as ghosthood is about emphasizing certain qualities within personhood, I posit this ghostly methodology as a sort of additive means through which to infuse one’s work and process with ghosts. How can I take each of the qualities of ghosthood into consideration when practicing?

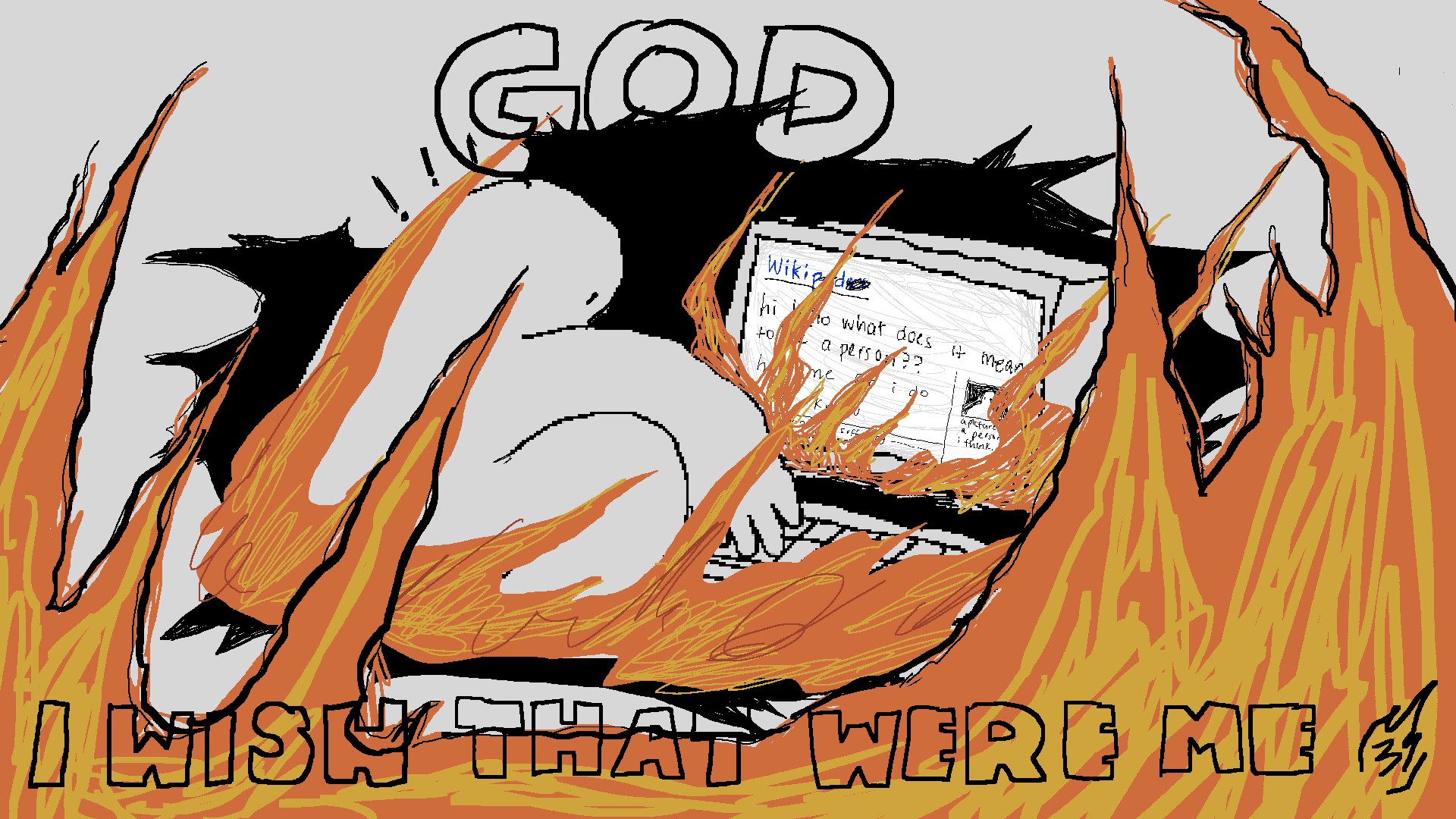

The subjects that feed my work, from architecture theory to web archiving to analog horror, are things that inspire me emotionally, and as such I treat them as parts of myself. Because of this, my works are often brought about by introspection, even if the topic isn’t typically considered personal.

When I work with a topic like technology, even though I’m inspired by its physical and functional aspects, I find its philosophical and emotional aspects to be just as important. Why does audio crackle make me feel warm and nostalgic? Why did the X-Ray instantly become a fetish object? Why do some video games make me homesick?

Such alternative narratives are unspoken ghosts, and they have haunted public discourse, gathered cult interest, and been developed into publications, courses, research projects. That interest is due to, and not in spite of, their deeply personal nature. In this vein, I would describe all my work as somewhat autobiographical. Linking these topics to myself allows them to fluctuate and change their mind alongside me. In doing this, I place myself as an unreliable narrator, highlighting the ephemerality and transformative quality of both the self and the topic at hand. Although I usually start with text as an outlet for my thoughts, I lean towards the media of video and scenography because I feel that they allow me to combine the indisputable factors of the world with my own subjective perception: biases, memories, even fabrication. I find that this play between the real and the performative, or even fictive, is key to creating an atmosphere of haunting. There is, however, more to the process than just the atmosphere; within my methodology, I utilize the qualities of ghosthood to embed ghosts into the fabric of the work.

Allowing space for fluidity within my practice means that I treat all my work as open-ended, and as an embodied exploration of a certain question rather than a means to an end. It also invites the diffusion of different media into each other, and the inclusion of previous works in the creation of new ones, resulting in the tendency to self-reference. I am inspired by the concept of lore, especially in the case of fictional subjects. Lore can be described as the body of knowledge regarding a certain topic, usually documented by a cult audience rather than institutions. In the case of fictional subjects, the lore is extracted from both the canon (what the author of the subject has established as true), and what the audience has deduced, theorized, or blindly accepted to be true.

Whenever I come across a piece of media that I enjoy, especially one with interesting worldbuilding, I find myself itching to know more: more than what the author has explicitly or implicitly told me in the work itself, more than what the author has divulged after the fact, more than what the audience has picked out from clues and easter eggs. I want to know everything, real and otherwise, even when it is contradictory, because it means that something has grown further than its author, and that, in a sense, it belongs to everyone, which means it also belongs to me. I also think that the existence of lore implies that there is always more to uncover, and that the web of everything stretches much further than we think. It inspires me to keep secrets in my work– that isn’t to say, make my work inaccessible or pretentious, but to treat it like an inside joke. To keep parts of it for myself, so as to stop it from becoming disingenuous, to excite others into wanting to know more than I’ve given.

Absence is a pillar in hauntological thought, which suggests that being is inexorably linked to haunting, and nothing exists positively, but that a subject’s existence is based on the absences surrounding it (15). In my work, I link absence to omission. Every presence (text) alludes to an absence (subtext), and I try to play with what is told and what is hidden. To embrace this is to make room for interpretation and forego straightforward expression and representation. “The interest here, then, is not in secrets, understood as puzzles to be resolved, but in secrecy [...]” (16).

To create my own lore, I allow my work to be polluted with itself and with the narratives and truths that are canon in my own internal view of the world– which, in itself, is polluted with all the fragments that have contributed to it. Keeping pollution and transformativeness working in conjunction within a methodology means saving space for that lore, along with the didactic source material, the curious epiphany that sparked the idea for the work, the various artistic inspirations that contributed to its buildup– while breaking down, rearranging, and reconfiguring the reference material.

Nonlinearity in my working process means breaking the chronology and playing with the rules of storytelling. I understand nonlinearity not just as a collision of times, but as an indifference to time— a decision to follow an order that is more emotive, personal, and narrative.

The artworks that I look at for inspiration usually have an affinity for symbolism and theatricality, while maintaining a sense of humor. I find that humor creeps its way into my work whether I intend for it or not. Perhaps it’s my way of making sure that the work reflects how I feel about the themes I delve into: that even though they may appear serious, I think of them as friends. And like a friend, I am interested in figuring out their quirks, in playing alongside them and, naturally, in poking fun at them every now and then. It makes me happy when other artists seem to feel the same way.

Chapter Five: Ghosthood: A Companion

Ghosts are important because they challenge the binaries and standards that uphold the rigid structure of our world. Once we learn how to look for them, we can see that they’re everywhere; they exist because we exist, and because we leave traces. They manifest themselves in instances of haunting, which we experience as inexplicable feelings often tied to time and our position within it. I looked to technology and place for this reason, that they carry a quality of something beneath the surface, be it in their history or our own history in relation to them. They may inspire feelings of familiarity and nostalgia, but their tendency to age and transform and become obsolete can make us feel distant from them, and it is in that paradox of distant familiarity that ghosts build their homes.

At the start of this journey, I was concerned that there is nothing to me beneath the surface of external influences: the people in my life, my likes and dislikes. I was afraid that there was no core, nothing I could point to and say “this is who I am”. I look back at it fondly now. I am no longer interested in being an unshakable absolute. At the core there is a blur, where my feelings and the things I tell only to myself live, and those things are in constant motion. I live in many houses. I am a ghost haunting these houses. I am a haunted house. I fold these affirmations into little charms I keep in my pockets. I’m asking you to do the same. Look for the ghosts in yourself and everything around you. Leave your own ghosts in the places where you can’t find any. Change your mind, your feelings, your inward and outward expression. Let your loved ones, your favourite movie, the rooms where you hang out leave marks on who you become every day. Keep secrets. Keep your ears pressed to the walls and wait for the stories that only get told in whispers. Those who say that time is unkind only see it move in one direction. Time can just as well be kind, romantic, hilarious. I think if we let ourselves, our houses, and our histories be haunted, we’ll be better equipped to tear at the surface of the same old stories we’re sick of hearing. The way we feel about things is as true as their atomic concoction, and the fact that our feelings change makes this all the more true.

References:

1. Blanco, M.d., & Peeren, E. (2013). The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

2. Mbembe, A. (2001) On the Postcolony (1st ed.). University of California Press.

3. Derrida, J. & Stiegler, B. (2002) Echographies of Television: FIlmed Interviews (J, Bajorek Trans.). Polity Press.

4. Used here to mean a way of being, creating, interacting, and experiencing.

5. Gordon, A.F. (1997) Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota Press.

6. Place is used here to mean any location, physical or virtual. A room, a city, a specific bench or sidewalk.

7. Gunning, T. (2007) To Scan a Ghost: The Ontology of Mediated Vision. Grey Room.

8. Mayerfeld Bell, M. (1997). The Ghosts of Place. New York: Springer.

9. Trigg, D. (2012). The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny. Athens: Ohio University Press.

10. This quote was written in French. The translation used is taken from The Architectural Uncanny by Anthony Vidler. Although it originally references houses that have been abandoned, I think it’s relevant with places that have been stripped of their history for the sake of economic development.

11. The term “virtual space” here includes more literal interpretations such as virtual reality (VR) environments and the 2D or 3D digital environments used in video games and animations, or looser interpretations such as chatrooms and cyberspace in general.

12. In reference to this line in Neil Gaiman’s 1996 novel Neverwhere: “There are little pockets of old time in London, where things and places stay the same, like bubbles in amber”.

13. Frankham, J. (2014-15, December/January). Found photos: Rich Vogel isn’t a photographer, but he may be responsible for the finest piece of photojournalism, ever. Pro Photographer, Issue 009, p. 26-27.

14. Fisher, M. (2014). Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures. Winchester, U.K.: Zero Books.

15. Fisher, M. (2014)

16 Davis, C. (2005) État Présent: Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms. French Studies.