mind

Check-in with... Stéphanie Janaina

Berber Meindertsma

Berber Meindertsma has been with Het HEM since its founding in 2019. Alongside her responsibilities as development manager, she has curated and cultivated public and community programmes for Het HEM. She continues to develop her own research interests by writing on topics concerning hosting, hospitality and resonance in art.

mind

Check-in with… HMTP talents and coaches

After the music video release Vamos by KG and Fabs, a track written during the Homebase Music Talent Programme (HMTP) Writer’s Camp, Berber Meindertsma speaks with them and two of the coaches of the camp.

interview

Check-in with... Wil Spier

“If people are interested, they understand everything in the world. The problem is getting them interested.”

interview

Introducing Future Artefacts FM

From September 2023 to February 2024, The Couch is hosting 4 episodes of the London-based radio show Future Artefacts FM. Together with the first episode, we sit down with the initiators Nina Davies and Niamh Schmidtke to give you the full story behind their radio show.

interview

Check-in with... Sara Koops

Ever wondered what boxing is all about, and what art might have to do with it? Sit back and enjoy this check-in with professional boxer Sara Koops, who participated in the Chapter 1NE Box clinic at Het HEM in 2019.

mind

Check-in with... Maarten Spruyt

We sat down and looked back with Guest of Chapter 3HREE Maarten Spruyt, known for his work as a curator, art director and stylist, with an incredible knack for beauty and sensory perception. "I try to make exhibitions which make you look inwards, feel uncomfortable and sit with that for a moment."

essay

Hospitality on demand

Can the concept of hospitality provide us with a critical lens to explore what kind of relationships socially engaged art institutions can build online ?

20

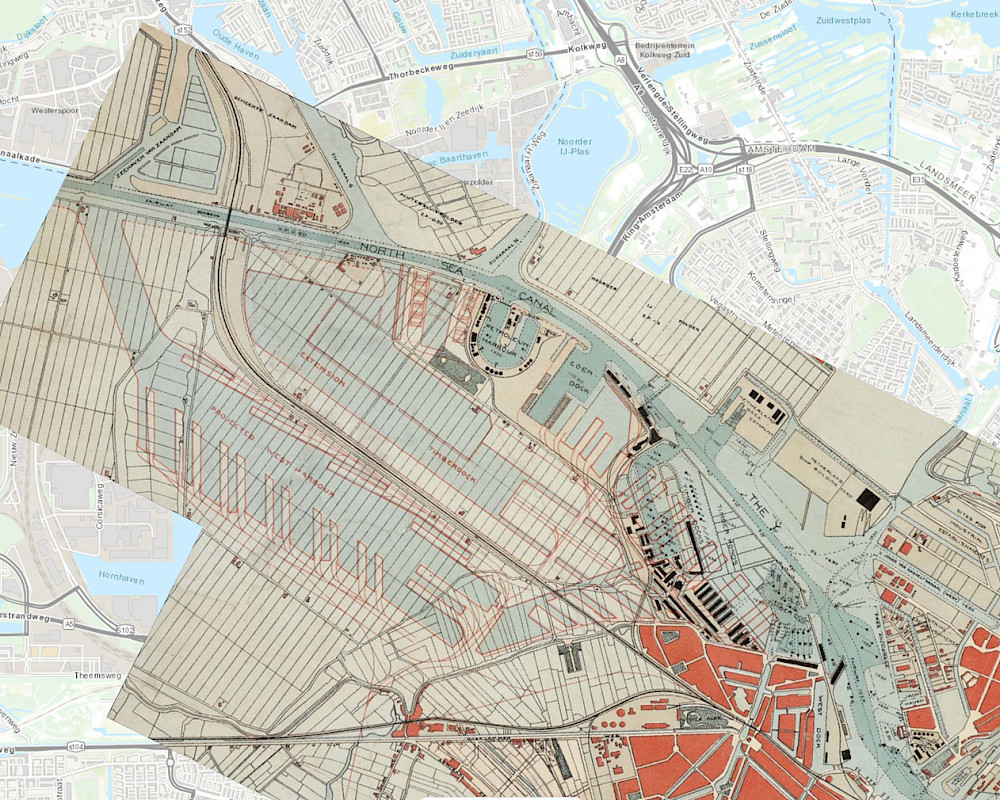

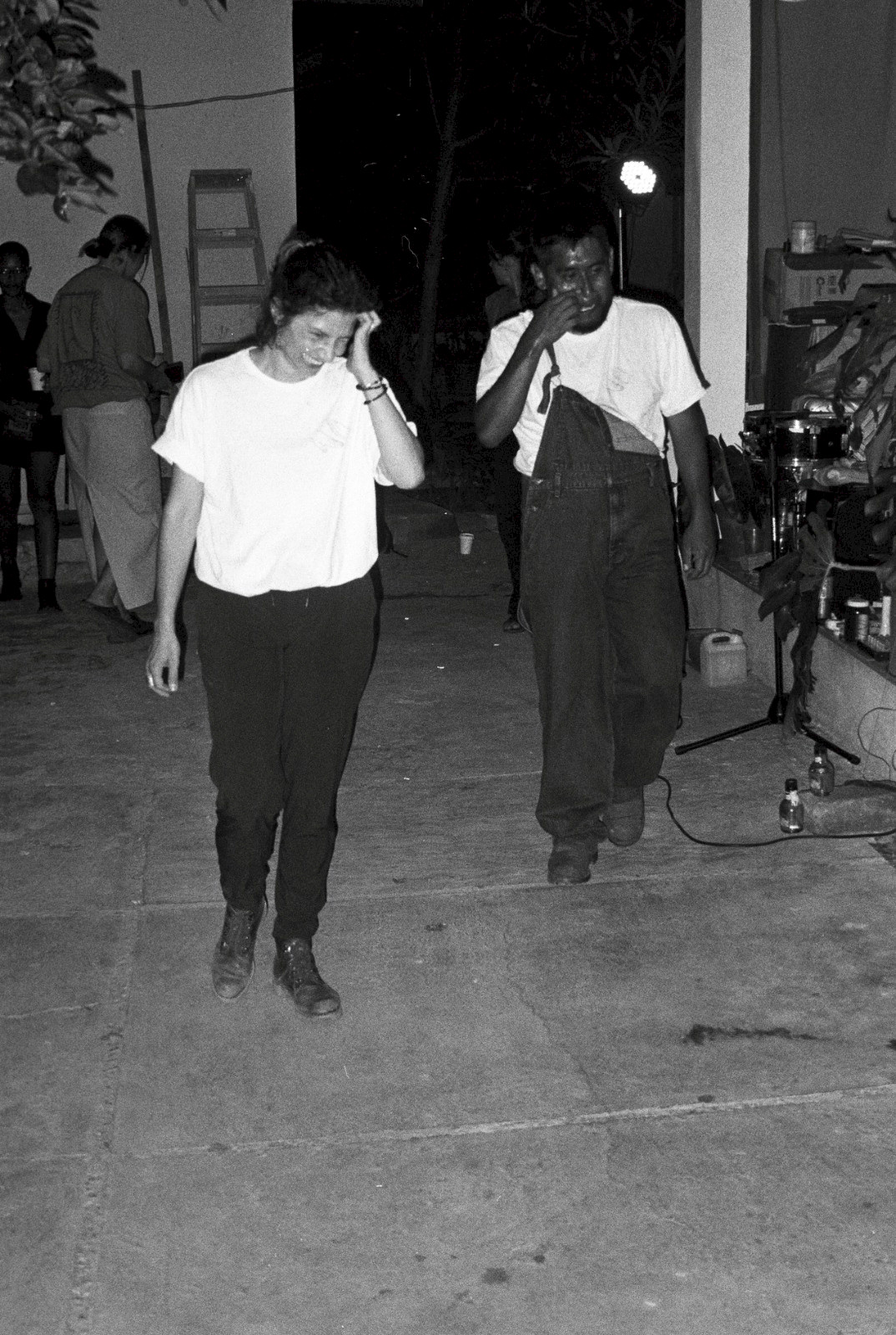

min readStéphanie Janaina is a performer and choreographer from Mexico. She is the first person who has ever danced at Het HEM – 3 hours non-stop on the concrete and ever-dusty floors of the Grey Space. Nicolás Jaar played music. Together they performed as ¡miércoles! - the name Jaar and Janaina have given to their collaboration – as part of Chapter 2WO: Nicolás Jaar & The Shock Forest Group in 2019.

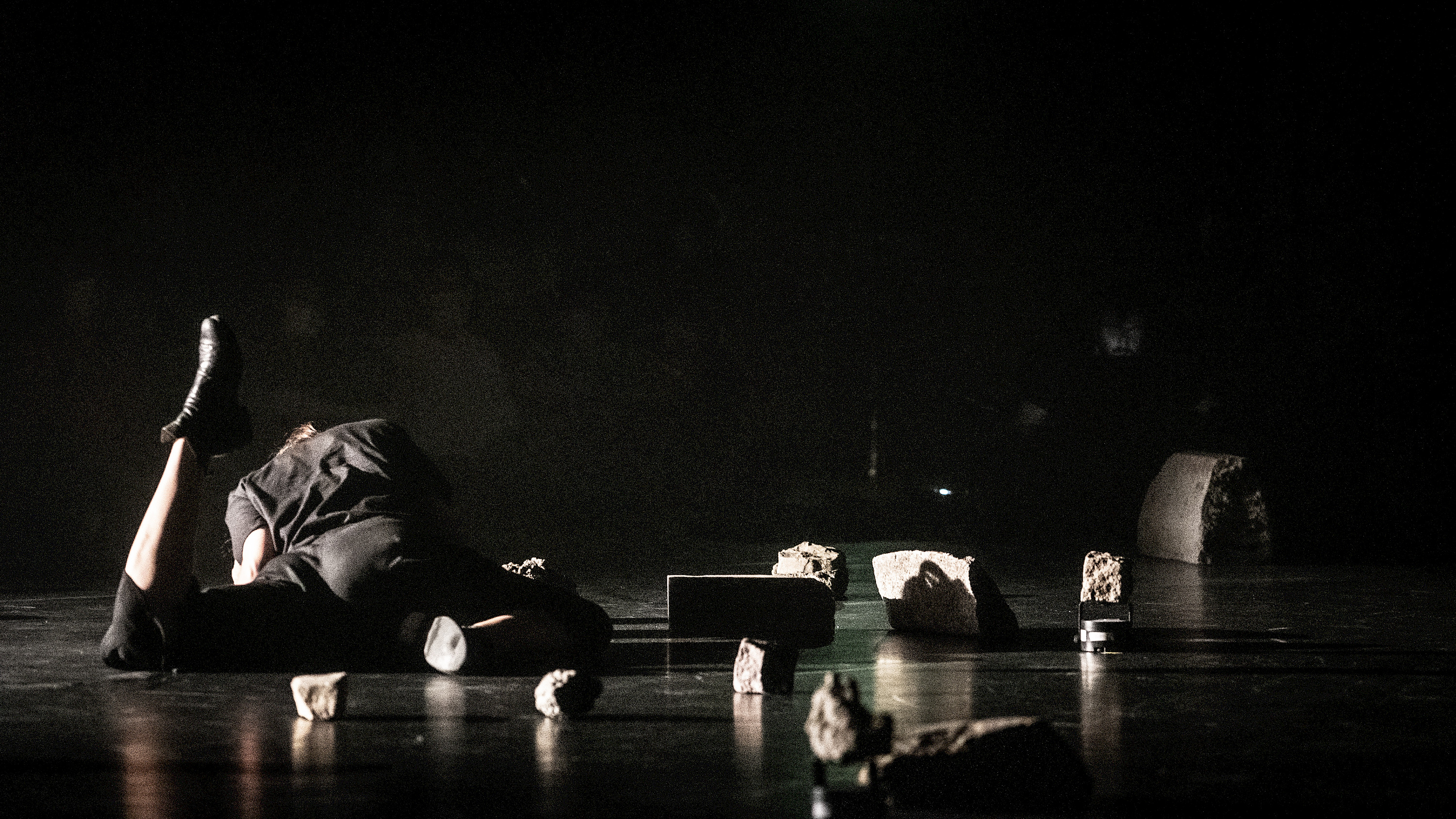

I will never forget this performance, nor the day that it was on: 2 November, día de Muertos, Day of the Dead. Before the performance started, they handed out booklets as offerings of sharing space together. They asked the audience to write or draw something and offer the booklet to another being at the end of the performance. Everyone was silent for about half an hour. It was a moment of contemplation and inner preparation before being taken into a meditative state. In the performance, hours seemed to pass like minutes. The sun went down and the room turned dark. With only two tealights as light sources, all eyes were transfixed on Janaina’s body moving through space.

Almost four years after this magical performance, I speak with Stéphanie Janaina over an online video call. She’s in Mexico and I’m calling from home in Amsterdam.

“How to talk about the body in a country where the body disappears?”

Hi Stéphanie, it’s so nice to speak with you after so long. I’d like to ask you about ¡miércoles!, the Day of the Dead and your artistic practice, but before we go into that: how are you and what are you up to now?

Stéphanie: I’m doing well, I’m in Mexico City and just came back from a residency in Oaxaca in South Mexico. The residency is called Yutindudi, and I’m one of the co-curators together with artist Rolando Hernández, who actually also came to Het HEM at the start of Chapter 2WO to perform. This is the third year of the residency, which revolves around the question; what is the potentiality of destruction? Destruction has been an interesting topic for us, as we had been working in the experimental festival industry for a long time and wanted to start and learn from scratch again. The interest in the potentiality of destruction grew when COVID-19 happened. That was a particularly hard time for dancers and other performers in Mexico as there was no governmental support. People lost their income overnight. They couldn’t perform on stage anymore. But at the same time, performing at home also became a mode of survival. The meaning of what a stage is changed. That’s when we became interested in how perspectives can evolve.

We started the residency in summer 2021 in a ranch that belongs to Rolando’s family. The first two years we kept the residency intentionally very small and closed off from the village community, as there was no COVID-19 there and we didn’t want to risk giving it to them. This is the first year that we opened it up to the village and invited the children from the Banda de Aliento (wind orchestra), a very typical Mexican orchestra, to take part. It was very nice to see how the children reacted to the exercises proposed by the artist residents. We filmed the process, as well as other areas of the mountains and the community, and are now editing that as the second part of the documentary about the residency (you can see the trailer of the documentary here below). We also made a music video, which was very fun to make.

It is very interesting to develop the residency over the years, as this is such a special place. The village is in the mountains and there is a lot of erosion there, which has turned the place into a red sand desert. The community is very united and works hard to create something fertile out of this desert land. They for example plant trees every year; we are trying to document this development and show it in the documentary alongside recordings of the workshops.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into your practice. I know you as a dancer and choreographer, but from what you’re telling us now it sounds like your work unfolds in multiple directions and long-term collaborations. Could you tell us a bit more about what drives you in your work? What are you investigating or trying to unpack; and how are you using dance and choreography to do so?

Stéphanie: For over ten years I’ve been researching fragility. I’ve been asking myself what it means to be fragile. By being female, you are imposed to be fragile by nature. I come from a line of women that have never shown their fragility whatsoever. They are very strong, autonomous and independent. Fragility therefore became a very interesting word to me: it was part of me, but I didn’t know how to show it. The first time I saw my grandmother being fragile, I started to wonder why we are so afraid of this word. I started to navigate my own fragility in different places. I went to China and to Hong Kong to put myself in places where I did not feel comfortable at all; to try and understand – with my body – what fragility means.

Today, I continue this work by adding anger to the equation. Women and children are not allowed to be angry. Angry women are set aside as hormonal or hysteric and children as being spoilt. If anger is suppressed it only comes out when we are really fed up; in episodes of rage. In my work, I try to understand how the body gets to that state of anger, and how we can continue in that state and create a potentiality out of it that does not hurt us but works with us as a little generative fire. Social movements work a bit like that; as they start from rage. I look specifically at the Mexican social context, where women are murdered continuously (12 per day), and the outrage we feel towards this is categorised as hysterical. Society is blinded by the demonstration of anger and is unwilling, or unable, to look beyond to see its roots.

The body is always my start and endpoint. I therefore consider myself as a dancer, even though I love to think from the choreographer’s position while working. For me, it’s not about the image that is created, which is more the terrain of the choreographer. It’s about the bodily experience I can share and convey. A question which has been haunting me for over 12 years and has been a driving source since I once saw it written on a sign during a university protest is: how to talk about the body in a country where bodies disappear? How to deal with disappearance, with violence, with anger? With the fragility of the body? Everything I do is related to these questions; the how.

Living and working in Mexico: a love and hate relationship

You mentioned that you’re in Mexico City now. Is this also where you grew up? Could you tell us a little bit more about how that was for you?

Stéphanie: I grew up in Mexico City, which was complex. As a child I was surrounded by grown-ups who said that everything is possible - the American dream. When you get older, you start to learn what that means. In Mexico the American dream is more related to reality. It means that the best and worst of humanity is possible. I’m totally in love with Mexico, but it’s a fatal love; it’s a very passionate relationship. You can love it and adore it as much as you can hate it. That was very present when I grew up. It is wonderful to be able to do anything; to start working as an artist from scratch and make something with little money that relates to others. But the other side of the coin is that violence is a reality.

To give you another example: in Mexico we say ‘mi casa es tu casa’, my house is your house, and we really mean it. You can go to someone’s house and they will feed you and give you anything they have, even if it’s very little. Mexico really has the warmest people. At the same time, you can have friends who have been murdered. I myself have lost activist and journalist friends. People disappear constantly; it’s a reality that you can’t escape. You feel that everywhere. This contradictory experience has also influenced me in how I think about fragility. It can mean so many things - bad and good.

You already felt that when you were a child?

Stéphanie: I did, it’s very tangible. Children can feel the violence and tension already at a young age.

When did you leave Mexico for the first time?

Stéphanie: When I was 18, I went to Paris to study for a year, I hated it and came back to Mexico to dance professionally. Three years later, I left Mexico again for almost 4 years and came back again. This has been my dynamic over the last 20 years, mainly because everything is too intense here. As a dancer and a woman, my practice naturally evolved into becoming more involved in different social fights, defending bodies and their rights to freely move. As fragility has been my research motor, this has also led me to create many meaningful connections, especially with victims of violence and forced displacement. There have been many points in my life when I feel so impotent that what I do seems to have lost all its sense. I become paralysed and that is the breaking point for me, when I know I need to run away; that is my fragility.

¡miércoles! performance at Het HEM

I would now like to look back to the ¡miércoles! performance at Het HEM. This performance is part of a longer series you’ve developed with Nicolás Jaar and have done in various places - from deserts in Sharjah to former butcher shops in Rome. Can you tell us a bit more about ¡miércoles! and how the collaboration with Nicolás started?

Stéphanie: We met through a mutual friend, singer Roberto Lange whose artist name is Helado Negro. I used to collaborate with Helado Negro as a dancer and we were about to open a concert for Nicolás in Guadalajara. Roberto told me that I should really meet with Nicolás as we would have a lot in common. We were both in a moment where we needed silence. For me it was a silence in dance; there was so much death and dying around me, how could I talk about the body in a time of disappearance? It felt absurd for me to dance, I was paralysed. Nicolás was in a similar place, but with other questions of course, relating to his cosmology. We met and became friends and companions in this reconciliation process on what to do and how to continue our work.

What we did was that we started to improvise together in a format in which we didn’t see each other as we were in different rooms. It was easy to listen to each other but the goal was to find other ways to show ourselves; to feel and understand each other from another perspective. We did this for about two years just for ourselves, with no further purpose. One day we decided to make a piece together. We worked for 3 months on the script, scenario, choreography and sound. Every detail was planned. Then, one day, nothing made sense - we realised we were going back to what we were actually running away from. So we decided to put all those thoughts and research in a small publication. This became the fixed ground to ¡miércoles!, a publication containing the questions, research and thoughts we ask ourselves prior to each performance that structures our improvisations. To us performing is about confronting a moment; creating a relationship with the space, the local geography and the people who are present. At Het HEM we wrote a lot about death: what it means to us, what it means culturally and historically, but then we erased it all. We realised that it’s not for us to talk about death. It’s for death to talk about itself. That can only be done through the stories of other people being present.

That’s beautiful, and so clear. Was it also clear when you were performing?

Stéphanie: It’s always very clear in my head, but it does take some time to put it in clear words. Another reason why I’m so grateful to be working with Nicolás is that he has such a sharp mind and can find the right words much quicker than I can!

I’m sad that we don’t have any recording of your performance, as it was so beautiful. But then I do think that for the people who were there, the performance will be forever stored in their minds.

Stéphanie:That’s also the nature of ¡miércoles! though, we never want to record it. Recordings create an expectation of what it will be like, while for us ¡miércoles! is about building a new structure in our mind each time.

Why is it called ¡miércoles! ?

Stéphanie: For various reasons actually. It came from a silly thing, miércoles means Wednesday in Spanish. We were both born on Wednesdays and we met on a Wednesday. I also like how it sounds. But miércoles also means shit in Chile, it’s an expression used by old people, I think. Miércoles also comes from mercury, and we like what mercurial is like; it’s very much related to improvisation; it’s ambivalent, changing in patterns and elemental structure. Mercury is a Roman god, who could adapt to anything and really knew where to go because he was prepared and trained in following his instinct. We prepare for months in advance and then at the moment of the performance we like to let it go, and - like Mercury- be in the moment, feel and understand the situation instinctively.

Día de Muertos

Today is día de Muertos and I miss the scent of the cempasúchil flower mixed with the smell of the millions of candles that light the way home

You briefly talked about the Day of the Dead playing a central role in the ¡miércoles! performance at Het HEM. In the booklet you also share a bit on what the day means for you. I’m curious how you experienced the Day of the Dead when you were at Het HEM?

Stéphanie: We didn’t actually choose the day for the performance, but it made a lot of sense. Of course, in this place, a factory where weapons were built, our ¡miércoles! performance could not be related to anything else but death. To us the building was calling out death. We started to think about how we could bring all those spectrums of life and energy to it. That’s also what I think is the essence of Het HEM: it’s about bringing life to the former bullet factory. That’s very close to the intention of the Day of the Dead in Mexico: it’s about commemorating life, not mourning death. It’s very colourful. People cook for the people who have been dead; it’s about inviting the dead to the table. You bring joy and love to those that you miss. At Het HEM it could only make sense to bring that memory of life into the building.

I experienced the performance just like that; I put my body at the service of feeling that energy between life and death, to see where I could move and where that could bring me. The movements I made were not from anything I’ve been taught at dancing schools, but came from me, from the guts, from the soul, from the heart.

Something beautiful actually happened when we were rehearsing. Nicolás had to leave for some time to meet with you, and left me in the Grey Space with a music recording. While that was playing, I started to think from my body and became very aware of the walls and stones in Het HEM. The stone walls bear the history of the building; they are the remaining witnesses of time. After this initial spark at Het HEM, I continued working with stones for a long time. That music recording became part of Piedras (stones), one of Nicolás musical projects. Neither of us knew that we were both working on stones at the time, and it’s something we discovered months later – that was so magical!

Do you hold any special memories of the Day of the Dead you like to share here?

Stéphanie: That would be the cemetery on the street where I grew up, and the cempasúchil flower. The flower has a very special smell. On the Day of the Dead all the streets are closed off, and fill up with people walking with that specific flower, candles, food and drinks to gather around the cemetery. The smell of that flower is all around my house; as well as the cacophony of sounds (as people play different types of music for their lost ones); people laughing and crying. At the same time there is also a permanent silence in between all of this. While it’s very lively, you can also feel that people are reflecting on the absence that day. Between all the noise is also silence.

Do you have any recommendations on how people could celebrate it at home?

Stéphanie: In Mexico, we make a little shrine with family pictures of those who have died. We make it really colourful and use a lot of flowers and candles, as the day of the dead is not about being sober or mournful. This may sound funny, but we also make skulls out sugar and put the name of the person who has died on their foreheads, and some mezcal or tequila. Putting out alcohol is a nice thing to do, because the alcohol evaporates, so you have the feeling that they have really been there. The Day of the Dead is about feeling the energy of those who have passed away, and showing them that you are ok; that everyone is doing well and that they are still part of your life. That’s also why you create a place at the table for them and cook their favourite meal. You show them that you still have a place for them in your heart, at your table, and that you haven’t forgotten them. We are sad that they are gone, but still live with them**. Ultimately the day of the dead is a celebration of life. There is not much crying – some people believe that the crying makes the dead come back and prevent them to go to heaven**.

What are you going to do this year on Day of the Dead?

Stéphanie: I will be in India for a residency. I’m there all of November, working on the structure for a new performance. It’s a continuation of the work about anger and fragility, that I have been doing with women and children. I started this solo project in Mexico, then went to Uruguay, Chile and now India. When I’ll be there, it’s the celebration of light, Diwali, which is their Christmas holiday. I think I’m going to combine traditions of the Day of the Dead and light. I will commemorate my mother, who has passed away this year, and ask her to come back. She always wanted to go to India but couldn’t, so I hope we can be together that day in India.

Collaboration and community: being anonymous in order to be everyone

”My work is related to anonymity; it’s not about me but about everyone.”

What does collaboration mean to you? How do you sustain relationships when you’re traveling so much?

Stéphanie: I’ve questioned collaboration a lot. I grew up with my mother and my sister, and my mother always used to say that we are a community. To make anything happen, we had to be together and support each other. This has influenced me in how I work; everything is a collaboration and all aspects of the performance are of the same importance. In my collaborations, I strive to engage and sustain a horizontal dialogue.

In that same vein, I consider my collaborators as friends and the other way around. I have a lot of friends whom I don’t see but who still have an impact on my work through conversations we’ve had. Even though they might not directly or concretely work with me on a project, I consider them as my collaborators. They help me to understand myself better and create a coherence out of ideas that come to me instinctively.

My father’s family from Oaxaca also influenced me in how I think about collaboration. In Oaxaca the community ethos is very strong. Everyone has to work together; they take turns in leading the hard work in the mountains. This is what I saw when I grew up. Also in 1995, when I was eleven years old, the EZLN (Ejercito Zapatista Liberación Nacional) came down from the mountains and this made a big impression on me. They had masks on and so you couldn’t see their faces, but you could still see them. My work is related to this anonymity; it’s not about me but about everyone. I need to be anonymous in order to be no one and everyone. That conviction came from the image of when the Zapatistas came from the mountains.

I had the experience of you becoming no one and everyone at Het HEM. You were dancing in the middle of the room and all the attention was focused on you, but it wasn’t like we were watching you as Stéphanie Janaina dancing in the space. It felt more like we were one big organism, all connected in a shared energy that you and Nicolás created. I didn’t know the person next to me personally, but still felt a connection, a recognition, as the other human beings engaged in this experience.

Stéphanie: I’m happy to hear you say that, as that is what I pursue in my work. I have to erase myself in order to be anyone. This is how I can answer that question that is haunting me. I offer my body to become all the bodies that have disappeared. Before I do that, I look at all the spectators. I take the time to see everyone, I absorb their energy and then give it back. This act of looking is not about me seeing them, but about us all looking at each other.

Where can we see you next?

Stéphanie: Maybe at Het HEM next year. I’m currently working on a solo project, for which I am building the groundwork. It will be the first time I will talk from a personal perspective, so it’s as exciting as it is scary. I will be in touch when I’m ready.

That would be amazing, definitely keep us posted! Thank you so much for this conversation Stéphanie. Good luck and have fun in India!