essay

In The Door Opening of The Bedroom

Zazie Duinker

Zazie Duinker studied art history and writes about contemporary art, language and literature.

Maria Vorobjova

Maria Vorobjova is a London-based designer; artist; cyber sprite.

Her work playfully weaves together maps of ethereal (virtual;dream;club) worlds with saturated, shimmering threads.

essay

The Image of an Image is a Memory: Clash of the Imperial Gaze

Today, a walk in the museum is a walk with a camera. Is the hegemonic narrative of the exhibition questioned by the camera? Or does the camera become an accomplice to the museum?

essay

Thinking through the supermarket

Ilaria Obata takes a fresh look at the vast environment of the supermarket chain in this analytical essay.

fiction

Cup Run Over

smiling my best smile I asked him what sort of work he was in, my eyes moving down to the cup in his hand.

fiction

The Boys Next To Her House

"I thought about a cold beer and cigarettes in the garage. I’d kill for that."

fiction

Mademoiselle de Sade

"She cleaned him, made him pray; she ate him violently like a fat pig enjoying its last meal."

19

min readI travel between two, three, four bedrooms. It’s less promiscuous than it sounds; I take up temporary residence in my old childhood bunk bed, my partner’s attic room, the bed of friends whose cat needs watching and my own former bedroom that is now just a room with my bed in it. Funnily enough, with this abundance of rooms devoted to sleeping, I’ve been doing very little of it. My nomadic sleeping arrangement has left me restless. Not entirely surprising, seeing as I keep busy carrying my toiletry bag across the street to and from my partner’s house - much to the amusement of any curious neighbours. My toiletry bag and I are constantly on the move, passing through other people’s spaces without one of our own. It reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s case for the importance of women to have a room of their own. Women need, she contends, a room where they can write without interruptions and distractions. Interestingly, though, at no point in the book does she disclose what exactly she has in mind for this room, other than that it ought to have a lock. We do, however, get an indication of what it is not, namely a ‘bed-sitting-room,’ the option to which a female writer will probably have to resort in the absence of Woolf’s sought after room.[1] The impediments of the communal sitting room she describes (interruptions and distractions), but why exclude the bed from the writer’s domain? Why arrest writing at the border of the land of dreams?

Supposedly, there’s no space for it. The bedroom is conceptualised, despite its irrefutable three-dimensionality, as a one-dimensional space for rest. What an inaccuracy! Although undoubtedly a space for rest, it is far from one-dimensional. The bedroom is a multidimensional space encompassing a multiplicitous conception of rest that confounds the relational structures that govern the bedroom into a range of directions and proximities. It sees formerly dialectically opposing pairs such as idleness and fecundity shift positions, oscillating between antimony and harmony, as they disregard their borders and find a co-existence. The result of this is a fertile breeding ground, a bubbling brew pot brimming with potential.All of that is housed in the bedroom. I wish to plunge into this coalescence, this complicated notion of rest, and explore its intricacies.

Initially, rest is often understood as relaxation through the cessation of action or motion. The horizontal position that the bed demands seems only fitting then, and from there it’s a slippery slope to sleep. Many artists and writers have praised sleep. Fernando Pessoa, for instance, touches on his love for sleep recurrently throughout his Book of Disquiet, and even laments his inability to express it wholly. He writes:

If ever I were to obtain a pen so ingenious that it consolidated in me the entire art of writing, I would write a song of praise to sleep. All my life I’ve known no greater pleasure than to be able to sleep. The total cessation of life and soul, the complete expulsion of all living beings, the night without recollection and disappointment, to possess no past and no future.[2]

Is it really as Pessoa describes? Can sleep really be characterised as a cessation? On many occasions, sleep is hardly inactive. In addition to nightly kicks against your bedfellow’s shins or full-on sleepwalking, the mind can cause quite the ruckus. Even though I may be fast asleep, in bed my thoughts are far from dormant. Across the ridges and through the valleys of my sheets, they guide me as they show me to the reaches of my own mind; there where lie dreams of cardamom and oranges, broken vases and large castles where all the rooms are empty but for one. As if surprised by the capacity of my own mind, from time to time I’ll jolt awake and scramble to find my phone in order to write down the marvellous thought just delivered to me before it escapes, my bleary inability to focus pulling me back to sleep. If I don’t, I am guaranteed to spend the next morning grieving the sentence I briefly crossed paths with in the night.

Can sleep really be characterised as a cessation?

The animated corridors of my nocturnal mental palace thus complicate the priorly assumed restful quality of sleep. That is, if we maintain the first definition of rest as the absence of activity. But are the two really necessarily mutually exclusive? No. An alternative form of rest can be derived from mental relaxation obtained by engaging in activities with no particular end. Instead of bending to the rules of labour, this form of activity stands with its head held high in its uselessness. It can look like taking a stroll, listening to music, or daydreaming. Leaving this world behind in favour of a fantasy land and embarking on a mental voyage is arguably one of the most openly non-productive things to do. And as it happens, my favourite. Sometimes I daydream about a man who whistles with the wind, and other times I spend hours on the conundrum that is the incredible importance of useless things and I feel as though I ought to call it contemplation. Either way, as day turns to night, my wandering thoughts climb the stairs and pass through walls to work their way under the covers to rest on the pillow.

From there, the only barely formulated thoughts spread their wings and take to the sky as they become full-fledged ideas. In this tender stage they are nimble. Eager to dart away and flutter off the moment my attention falters, I have to stay close and tiptoe in their shadow, ready to follow their quick and light moves. Tauntingly, it seems, they zigzag across the room, occasionally looking back to see if I can keep up. At times this cat-and-mouse game is a joyous affair, that both of us participate in with a childlike fervour and inexhaustible energy. Other times, we are tired. Still, then, the whistle blows and the game commences. At this point the chase is a laborious undertaking to wear out my thoughts and arrive at a level of fatigue that will allow us to fall asleep. So, while lounging on the bed may not appear particularly physically tasking, the amount of energy coursing through such a reclining figure is incredible. No wonder my father recently exclaimed: doing nothing is damned hard work! He was talking about doing nothing as an essential part in the process of writing, and in doing so pinpointed the precise significance of the bedroom. For it is in this capacity that the bedroom is simultaneously the domain of laziness and productivity. It is the perfect site for their encounter, as it provides an arena of emptiness to run around chasing ideas in. Time disappears in the night; the insistent ticking of a clock is caught and strangled by the soft fabrics that adorn my room. Duvets, pillows and heavy curtains further ward off any sounds intruding from the outside world as they muffle the sharp pings of phones and the unwarranted rings of bicycle bells.

And yet it’s not silent in the bedroom. It has its own sonority. In contrast to the outside world so overpopulated by all kinds of sounds that each exist in isolation by means of their capacity to signify, the bedroom is laced with a melody. A melody strung together from muffled breaths, moans, whispers and the soft brushing of the sheets and the creaking of the bed frame. Or those little murmurs of contentment that sometimes slip out during the night when you ever so slightly lift from your sleep and roll over on your side to burrow back into the sheets. Atop the lingering lullaby that got me to sleep as a kid they flow. When I was little, my father used to sing me this one verse over and over again that I would never grow tired of. Arabine Koeterine van je trif troef traf - Prrrr, laat de beentjes gaan, the song goes. The part I enjoyed the most then, is also the part that interests me today: the nonsensical elements. Trif troef traf. Prrrrr - with great enthusiasm we produced these sounds together. Just like the indistinguishable sounds emitted into the bedroom throughout the night, they evade the constraints of language. They are illegible, non-structural, illogical. They are intuitive utterances.

Sometimes I daydream about a man who whistles with the wind, and other times I spend hours on the conundrum that is the incredible importance of useless things and I feel as though I ought to call it contemplation.

In this respect, I believe the private quarters’ much cited air of intimacy - usually held to pertain to sleeping or having sex - extends itself to this early stage of expression. It begins with the expression of subconscious feelings - think of angry huffing, silent wails, or a cat-like purring of comfort - and then moves on to a next stage of thinking. After all, that process is deeply personal and strangely vulnerable. In The Third Bank of the River, João Guimarães Rosa tells the story of a young boy who encounters the most beautiful thing he’s seen in his short life yet, a majestic turkey, and later that day finds that same thing cut up on his plate. The boy is consumed not by anger or sadness, but something else. He is shaken by the reality of, for the first time, not being able to comprehend something. “His small thoughts were still in the hieroglyphic phase,” Guimarães Rosa wrote.[3] I can experience a similar shaking sensation when I try to collect and put together the bits and pieces that the fluttering ideas have scattered across my room. It is laborious and humbling. It is like the dressing room of language, complete with its pre-performance nerves and jitters.

As I’ve travelled across more bedrooms than the four I started this piece out with, still, it’s proven difficult to immerse myself in this process. My latest quarters – what number am I up to now? Eight? Nine? - take the shape of a dorm. For the first time in years, I’m part of a collective, as opposed to my personal, nocturnal domain. My privacy has come to mean our privacy, like when I shared a bed with my sister until I was thirteen years old and she moved out. The double bed was nestled behind a low shelving unit over which three glass windowpanes extended all the way up to the ceiling like columns. On the other side stood the dining table. Our dad slept on a mattress on the floor next to us. Camping, we called it. The perfectly adequate room just one door away which housed our bunk bed remained unused. Later, I shared a bed with my mother until I graduated high school. She’d sleep while I stayed up entertaining teenage thoughts in the light of my computer. Apart from the occasional instance when a visiting friend would inquire after my bedroom and remind me of how unusual this arrangement is, I didn’t think much of it. It was normal to me.

After all, the private bedroom is only a fairly recent invention in the West. In her aptly titled book The Bedroom: An Intimate History, cultural historian Michelle Perrot traces the development of the bedroom from the communal heart of the household to sanctuary of individuality, noting the role of the bed along the way in this development. Leading up to the twentieth century, the former was the standard. Life, death, and everything in between commingled in one room. Illustrating the intimacy of these intergenerational dwellings, Perrot relays an 1840 account of a worker that reads: “‘So it comes to pass that beside my dying grandmother, my little nephews are loudly shouting their joy at being alive, deafening her with their noise.’”[4] Nothing separates these synchronous testaments of life and death. The grandmother’s only solace lay in the bed, a private domain within the communal space.

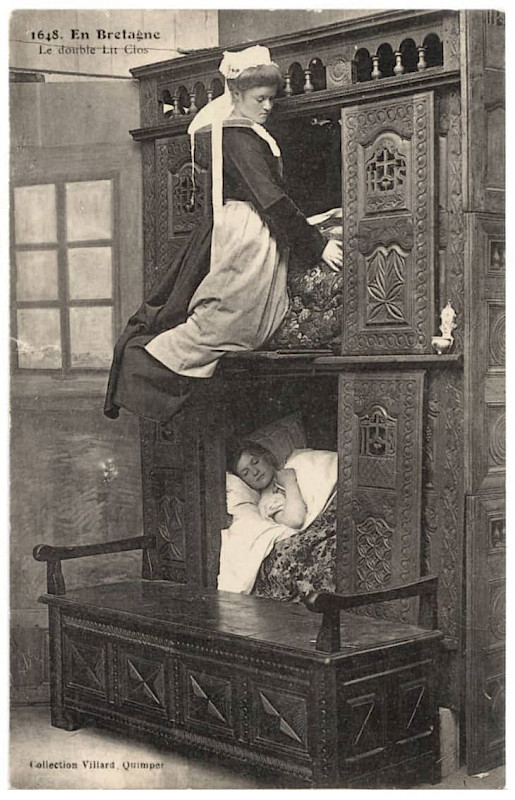

The development of the bed shows great variation across culture, class, region and time and doesn’t move along a straightforward progressive trajectory. However, there is a recurring motif across its many manifestations. Individual or shared, the bed carried the status of private domain within the communal space. Although the individual bed already emerged in Italy in the fourteenth century, the shared bed persisted in poorer households in (primarily) rural France for a couple more centuries.[5] Yet even those, in their shared capacity, managed to separate themselves from the rest of the room and assert their private character. The late medieval Breton box-bed, for instance, was a design that enclosed a bed, often shared with one or more family members, in a cavernous wooden construction. “Each box-bed was like an apartment unto itself:” Perrot explains, “when its inhabitant entered, when he had closed the two sliding doors, he was at home.”[6] It was, however, not the most comfortable of beds, and over the course of the nineteenth century gave way to a new mobile and affordable bed, following doctors’ pleas for individual sleeping arrangements and the iron industry’s ability to accommodate those.[7] No longer able to hide behind the substantial wooden panels, people resorted to a strategically positioned curtain to lend their bed some privacy. No wonder we stuff our bedrooms with voluptuous fabrics. A step up from curtains, feathered quilts, pillows and bedspreads piled on top of a large stuffed mattress provide the perfect hiding place. As such, even in a communal bedroom, the bed can function as an island of solitude. Even Georges Perec, undoubtedly well informed of bedroom matters after having written A Man Asleep, agrees by stating that, “the bed is … an individual space par excellence, the elementary space of the body, which even the man crippled by debt has the right to keep.”[8]

For me, having my own bed coincided with having my own place. I alternated between staring at my ornamental ceiling and flipping pages in Orhan Pamuk. Tonight, I lie on my back on a small mattress, looking out at seven identical beds, while the words in front of me only appear in the red light beam that aims from my forehead at the page. The headlamp is necessary because the big lights have been turned off to accommodate the varying sleep schedules that come together in a dorm. It testifies to the possibility of being perceived, and all the while I’m aware of that. As I lie there, headlamp strapped on and book positioned against my pulled up knees, I can’t rid the action of the possibility of becoming, at least partially, performative. For this reason, although it provides enough light to read, I can’t think in this light. My thinking could not possibly be performative. Sequestered within my mind, it lies outside of the terrain of the spectacle. And therefore, it’s incompatible with the communal room, where “everything’s a spectacle, and all the spectacles blend together.” [9] The private room, by contrast, provides a refuge from exactly this. As Kafka would have it: “’I cannot bear communal life with anyone. (...) I hurl myself into solitude as I do in the ocean;’” he sought refuge in his bedroom. [10]

This understanding of rest intrigues me: rest as relief from the public eye, from the otherwise inescapable fate of being perceived. In the dim candle-lit interior of the bedroom this form of rest is easily granted. It can remain obscure while the spotlight ruthlessly illuminates the public stage. Lately, however, the spotlight’s bright beam has been encroaching upon the territory of the bedroom. Against the backdrop of widely resounding clamours against capitalism and its smothering grip on the art world (read: art market), exhibitions and publications about slowing down and idleness shoot from the ground like weeds. Last year I paid a visit to How Rest The Brave? at Nest (The Hague), an exhibition positioning rest as a form of resistance against a productivity-fuelled and profit-oriented society. I distinctly remember for the first time reading Mladen Stilinovic’ The Praise of Laziness (1993) there. In this short treatise he writes:

Artists in the West are not lazy and therefore not artists but rather producers of something… Their involvement with matters of no importance, such as production, promotion, gallery system, museum system, competition system (who is first), their preoccupation with objects, all that drives them away from laziness, from art.[11]

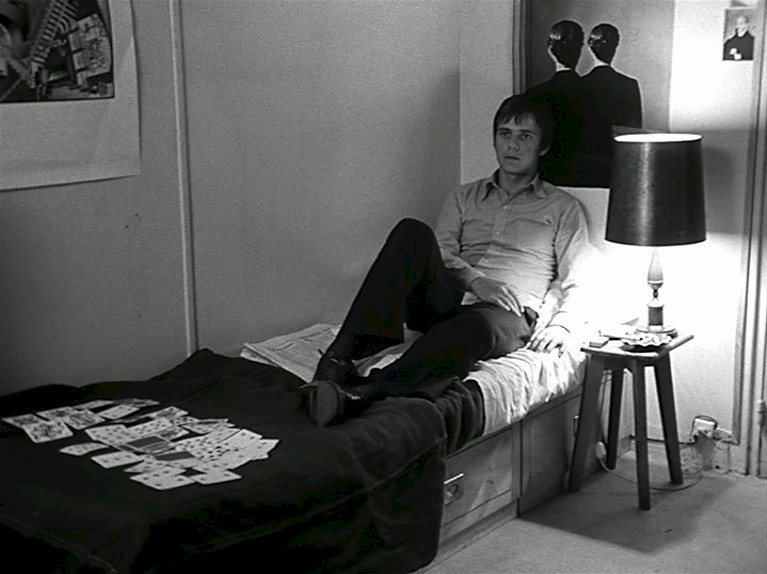

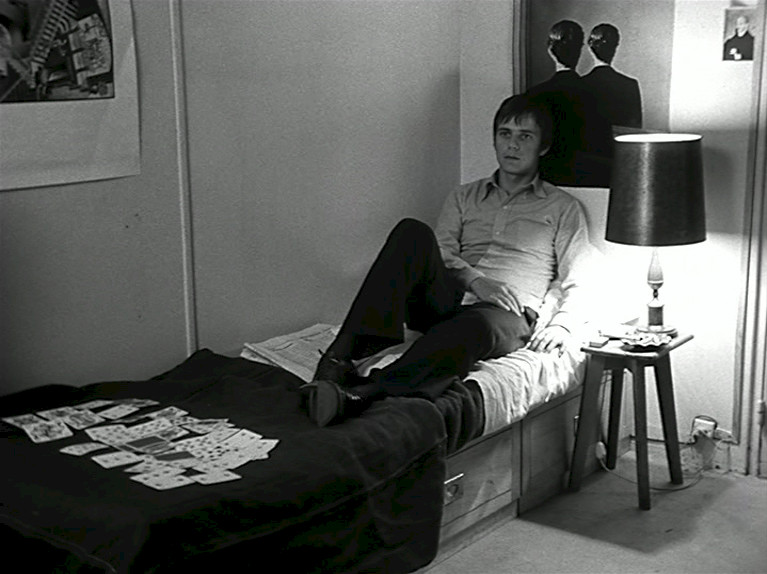

At the time, I was drowning in resume fillers of all sorts and trying to grapple with the consequential loss of my love for art that had inspired me to take on this work in the first place, watching it become submitted to trepidation. In this context, Stilinovic’ words sounded like a rescue call offering the beginning of a solution. Next to his praise hung eight black and white photographs of the artist lying in bed, accompanied by the title Artist at Work (1978). “There is no art without laziness,” was the message. [12] Recently, I encountered this work again in an article published in Mister Motley exploring the possibility of art within a capitalist system. [13] Again, it was praised as a significant work in the resistance against a capitalism-infested art world. Interestingly, it is also concurrently being advertised online for over $15,000. [14]

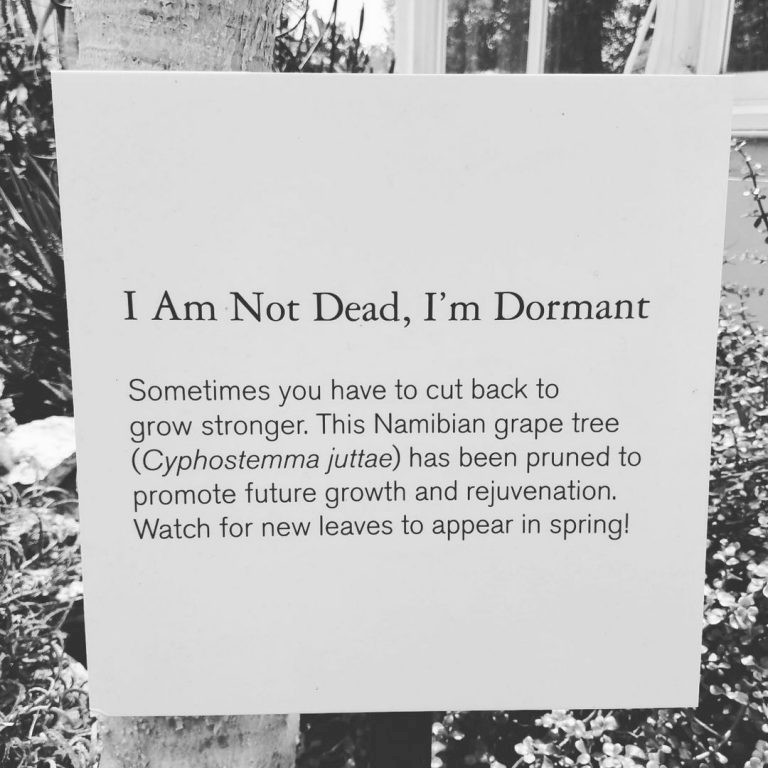

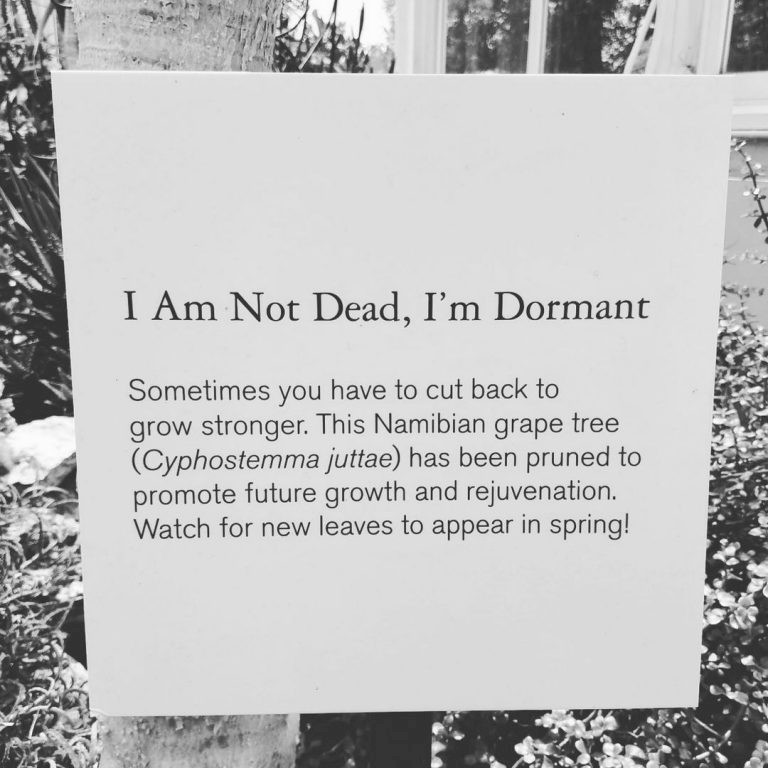

I wonder then, does the eventual success or monetary value (or are those synonymous?) attained by the work cancel out the laziness that birthed it? Is monetary value a measure of productivity? If so, does the value of Stilinovic’ message decrease as the value of the artwork-turned-product increases? Honestly, I can’t answer these questions. However, I can point out one factor that plays a part in all of this; intentionality. Whether Stilinovic intended to get rich off Artist at Work, we can’t say. We can, however, say that it is a performance and, in that respect, saturated with intention. The performed sleep is soaked through with the intention of being instrumentalised towards the development of an artwork, a success, a career. It is given an envisioned future and thereby acquires a directional attitude; a ‘towards.’ An initially seemingly insignificant sign on a tree I recently came across similarly illustrates this directional attitude. “I Am Not Dead, I’m Dormant. Sometimes you have to cut back to grow stronger,” the sign read. There is no laziness in this sleep. The tree sleeps towards strength like Stilinovic sleeps towards success. Such an instrumentalisation of rest echoes in its currently increasing popularity within the art world. Institutions are using the topic of rest as the building stones of their exhibitions, and in doing so apply a directionality to it and thereby in fact negate the very topic. The idleness at the heart of it is besmirched by the (monetary) value that becomes ascribed to the art the moment it enters the gallery or museum and becomes involved in its commercial endeavours.

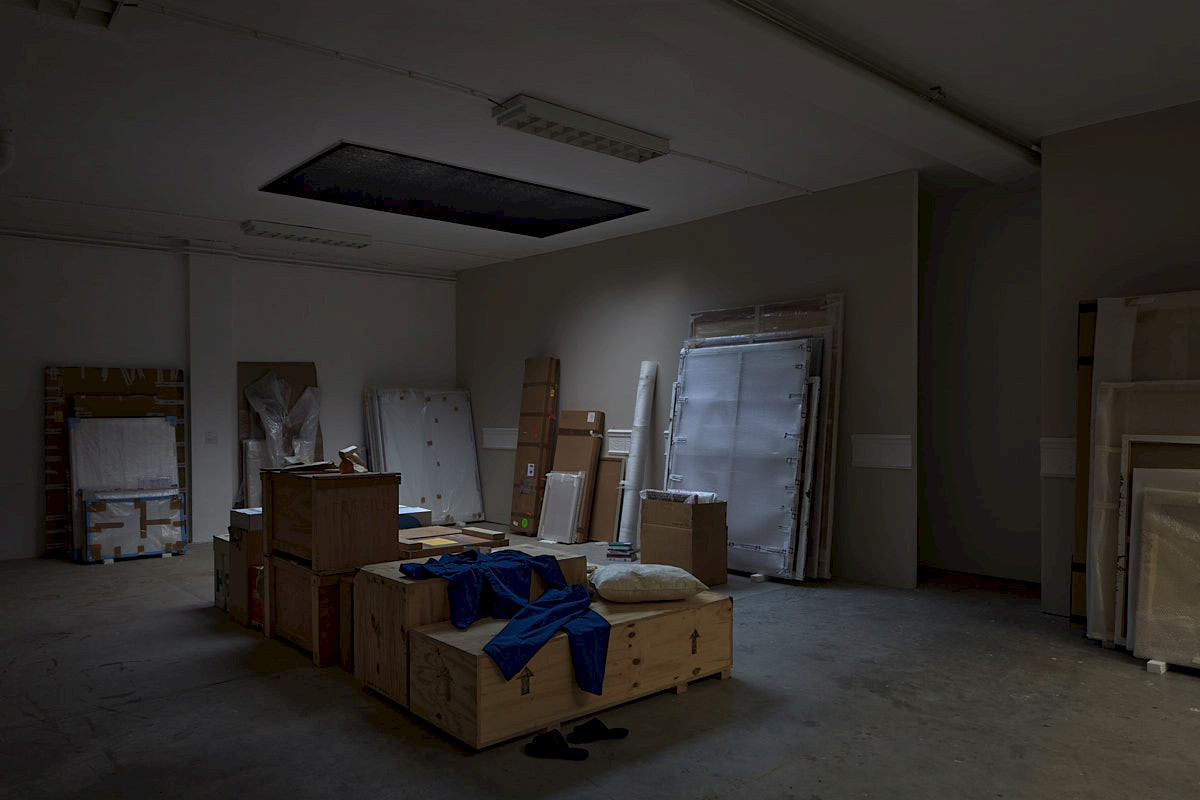

However, there is a way to bypass this pitfall. Last summer, I visited an exhibition in gallery Dürst Britt & Mayhew in The Hague that the gallery owner introduced to me as a dormitory for sleeping artworks. Under the actual title (、ン、), French artist Alexandre Lavet presented a space painted the same colour as his own bedroom’s walls and adorned with exact replicas of its wainscoting too, across which he’d positioned artworks boarded up in crates and paintings wrapped as if in a storage room. The archive-annex-bedroom reflected upon the processes that prefigure an exhibition, in doing so touching amongst others upon the role of contemplation and time. In their commitment to the work, the gallery extended its thought to the presentation format and decided to run the exhibition for ten months straight. Compared to the usual lifespan of a gallery show, a matter of weeks, carving out ten months for conceptual work - which is hardly the most lucrative - and thereby excluding any other commercial ventures is an openly defiant move in the eye of the otherwise fast-paced art market.

Regardless, it follows from this public instrumentalisation of rest that the politics of labour are slowly treading onto the sacred ground of the bedroom and contaminating reverie. Feckless pondering is at risk of being turned into a method, and that is something to be wary of. Although slight, there is an important difference between pondering having a place within artistic production and becoming its method. A method implies a prefigured plan of action, and consequently attaches to the pondering an intentionality. However, the bedroom doesn’t offer anything for this intentionality to attach itself to. For the bedroom is a liminal space. It sits on the verge between public and private, day and night, wakefulness and sleep, all the while unconcerned about questions of either/or, because it is both/and. It embodies the transitory space in between where temporarily, both meet. As such, the bedroom is the locus of a becoming, spread out across multiple dimensions. Every night, as I close my bedroom door behind me, this process is set in motion, and every morning, just as it is about to become actualised, it disappears. It is in this transient realm free of any sense of direction that the delicate synthesis of idleness and fecundity occurs and my thoughts are stirred to zigzag, flutter, and bounce off the walls.

Notes

[1] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (London: Vintage Random House, 2001), 81.

[2] Fernando Pessoa, Boek der Rusteloosheid (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 2005), 172. Translated by Zazie Duinker.

[3] João Guimarães Rosa, The Third Bank of the River (Amsterdam: J.M. Meulenhoff, 1993), 11. Translated by Zazie Duinker.

[4] Michelle Perrot, The Bedroom: An Intimate History, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), 35.

[5] Ibid, 39.

[6] Ibid, 37.

[7] Ibid, 36.

[8] Georges Perec, quoted in Perrot, The Bedroom, 60.

[9] Michelle Perrot, The Bedroom, 35.

[10] Franz Kafka, quoted in Perrot, The Bedroom, 58.

[11] Mladen Stilinovic, The Praise of Laziness, 1993.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Persis Bekkering, “Dit werk kwam in vijf minuten tot stand - kan kunst bestaan binnen het kapitalisme?,” Mister Motley, October 16, 2023.

[14] “Mladen Stilinovic - Artist at Work for Sale,” Artspace, accessed December 6, 2023.