essay

The Image of an Image is a Memory: Clash of the Imperial Gaze

Bhavneet Kaur

Bhavneet Kaur is an interdisciplinary designer and artistic researcher. Her kinaesthetic practice is rooted in spatial, curatorial, and editorial design. She explores the thematics of Identity, ancestral memory, and embodied female knowledge in the context of Indo-Futurity. She completed her M.A. in Contextual Design at Design Academy Eindhoven, for which she received a cum laude. Her recent work explores the operations of the Imperial Gaze within exhibition design and curatorial practices.

Maria Vorobjova

Maria Vorobjova is a London-based designer; artist; cyber sprite.

Her work playfully weaves together maps of ethereal (virtual;dream;club) worlds with saturated, shimmering threads.

essay

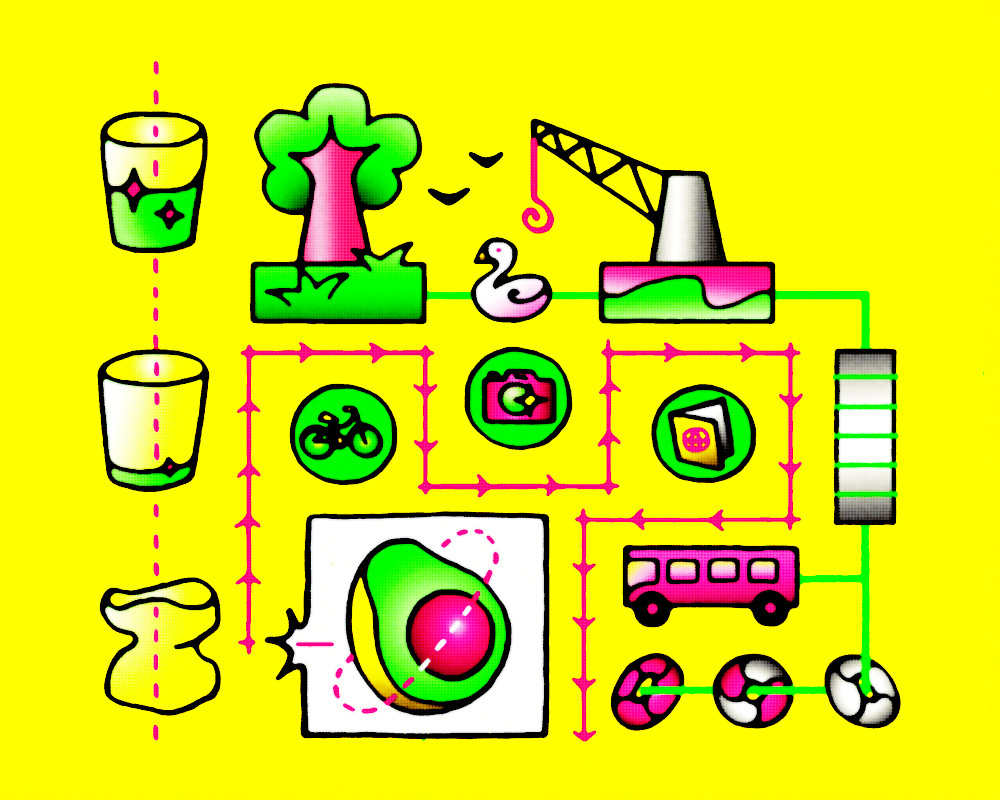

Thinking through the supermarket

Ilaria Obata takes a fresh look at the vast environment of the supermarket chain in this analytical essay.

essay

In The Door Opening of The Bedroom

'The bedroom is the locus of a becoming, spread out across multiple dimensions. Every night, as I close my bedroom door behind me, this process is set in motion, and every morning, just as it is about to become actualised, it disappears.'

fiction

Cup Run Over

smiling my best smile I asked him what sort of work he was in, my eyes moving down to the cup in his hand.

fiction

The Boys Next To Her House

"I thought about a cold beer and cigarettes in the garage. I’d kill for that."

fiction

Mademoiselle de Sade

"She cleaned him, made him pray; she ate him violently like a fat pig enjoying its last meal."

11

min read

When we walk into a museum, we look with two kinds of gaze: one of our eyes and the other of our camera. Which one is worse, I cannot tell. I ponder as I impatiently navigate this non-place.

Looking is a soft power we exercise daily. E.Ann Kaplan, Professor and Director, explores the imperial gaze as “Ways of being towards others and expressing domination.”(1) A relationship established between the coloniser and the colonised communities through looking is called the Imperial Gaze. This hierarchal looking typifies and neutralises the ‘other’ and becomes a means of apperception for both sides. A Gaze born out of oppressing encounters integrates itself into the apparatus of vision technologies, i.e. Camera and Exhibition. The conception of these tools overlaps with European colonial expansion. Perusing their initial intentions and offering an insight into the contemporary politics of display.

Exhibitions have historically been salient events for displaying and producing knowledge. One of the most influential exhibitions during the colonial era, The Great Exhibition of 1851, established the norms. “It reversed the panoptical principle by fixing the eyes of the multitude upon an assemblage of glorious commodities. Panopticon was designed so that everyone could be seen; The Crystal Palace was designed so that everyone could see. The exhibition transformed the many-headed mob into an ordered crowd, a part of the spectacle and a sight of pleasure in itself.”(2) Other fairs followed suit by displaying the material culture of colonised communities for the European audience. It is the ancestor of the biennales, international exhibitions, and museums that stand today.

The camera, as an embodied imperial eye, visualises colonial relations. According to Ariella Azulay, the camera shutter is crucial in establishing a universal right to see, creating violence by “dividing lines in time (between a before and after), in space (between who/what is in front and who/what is behind) and in the body politic.” (3) Photography documents the colonial gaze, capturing what was was necessary to remember. The language of photography is inherently aggressive, with subjects caught on camera and viewers exposed to the lens.

The eye and I walk hand in hand. What I see is what I am. The well-trained eye is superior to the spectator, aesthetically and socially. Today, as we stroll in the museum, the camera works as an extended limb. A clash between the two aforementioned imperial eyes is evident. How do these perspectives interact and influence each other? Does this conflict enhance or diminish the voyeuristic aspect of looking at art? Is the simple act of seeing left behind? And especially, which one is to be trusted? The exhibition and the cameras perpetuate the values of othering inherited from the past. It is impossible to display valuable art without being complicit in the violence of seeing, taking, and owning. According to Walter Mignolo, “Modernity is impossible without coloniality.”

While Anthropology Museums displace objects into alien contexts, contemporary museums continue to exercise white cube aesthetics with physical tools like podiums and glass vitrines. Therefore, the shutter heightens the decontextualizing aesthetics of an exhibition space. I walk as a fascinated observer of the human body caught in this condition, a camera-faced humanoid swarming in the corridors. The lens is slowly replacing our eyes, visualising for us. (No) Thanks to the imperial gaze. We meet only an ‘image’ with a meagre reference to the realities of the exhibit. It is a mirage for the spectator - a liminal experience that blurs the line between reality and dystopia.

The eye and I walk hand in hand. What I see is what I am.

Rijksmuseum, one of the most prominent art institutions in the Netherlands, holds almost 8000 objects capturing 800 years in time. In 2023, 2.7 million people visited the museum as one of the key tourist attractions of Amsterdam. My parents, who were visiting from India, and I were among them. We arrived prepared with our phone cameras and fickle attention spans, ready for a three-hour commitment. Our intellect lasted one gallery, our attention another floor. Our energies gave up at the sight of a chair. But our camera was eager and pushed us to look at what we came for: The Library Shot! After climbing three floors of long spiralling Dutch stairs, we reached one of the most clicked photographs of the Rijks Museums. A perfect one-point perspective shot of books lined up to the ceiling. It is not the library that took me by surprise but a three-foot-tall barrier between the railing and the visitor. The barrier transformed a live room with a simple glance from the meek corner of the building into a picturesque exhibit. A space otherwise wholly sensory and tactile is now an image under the demand of a camera. I wondered if there was a time when the barrier was unnecessary. When that magnanimous view of the library was discovered by a visitor with no intention of finding it.

An Imperial eye is solely capable of generating an image, which stands unchanged and frozen in time. The exhibited space is meticulously choreographed, like an algorithm. ‘Walk five paces, turn right, stare, two steps closer, stand still, and then walk away. Wait Wait! A fantastic background. Click and flash, a perfect shot.’ The image devolves from the bodily experience. “The visual exhibition aims to delight the eye but dies at the click of the camera shutter. The body is left behind.”(4) The museum space is responding to the needs of the camera and vice versa. When an object is close to the human body, it can be touched, felt, and smelled. ‘Strictly see and no touch’ constructs a distance between the self and the object.

Touch is prohibited and often punishable in a museum. The carefully guided footsteps of the public witness art with a disembodied eye. Bodies are left extracted. Feeling taxed and parched after a museum visit is a usual feedback. Modern imperial visuality aims to ingest the whole world with its gaze. Realism doesn’t cut it. “The imperial visuality itself is not private, but public: it is meant for all the subjects of the empire to see - but not to touch or to hold in hand. Seeing is privatised away from the body.”(5) Hence a disembodied and detached seeing sets roots in the post-colonial body. Where touch is non-existent and the body is emancipated from it. The herd of shutter-eyed humans is oblivious to this gap.

Art displayed over podiums safeguarded under glass cases are devoured as feasts. The shiny public properties are specifically for your eyes. The Mona Lisa gracing the premise of the Musée du Louvre in Paris draws you in. As one of the 8.9 Million who visited in 2023, my friend and I pushed through the crowds to find her, as were others. People were asking for directions to just one painting in their knowledge. The deep blue space has a distinguished aura. The whole room gravitates towards one focal point to capture a fraction of it. Does the Mona Lisa rattle the human need for proximity more than the need to look? Most certainly, looking facilitates the proximity. I was near her because I saw her. It’s enough. We immediately left the Louvre. Nothing else mattered, except a lasting shift in the vocabulary of our memories. While I was empirically subsumed by the painting, the crowds were busy taking pictures. They were fulfilled with the photograph, the sight they may not remember.

A contemporary jugalbandi(6), where the camera fools us into preserving memory by capturing an image of an image. McLuhan’s understanding of media as an extension of the human body acknowledges the unexplained numbness it brings to the individual and society. My glasses aid my weakened eye. It creates a barrier between the vulnerability of my blurred vision and the directness of the material world. They exist at the expense of my ageing body. Similarly, the exhibition & camera as bodily extensions seems to be outsourcing the act of remembering. Under controlled spaces, bodies can easily be conditioned into remembering a curated narrative with little room to exercise self-criticality. Truths are hard to challenge when presented in platers.

The spectator, now part of this staged reality, claims ownership at the clicking of the shutter and further exhibits themselves on social platforms of validation. Such are our memories now. False corporeality rarely visits again. I wonder what people do with the photographs taken in museums. Or is this just a unique manner of owning some unattainable public property? The visitor places their bodies beside the objects on podiums and before the displayed paintings. In an attempt to be part of the scenery by staging the self, the museum becomes a mere background. We decide that this spot is worthy of being a part of the frame and hence it is a part of us. The image of your perception. “The self-regulated audience is self-exhibiting now.”(7)

The spectator, now part of this staged reality, claims ownership at the clicking of the shutter and further exhibits themselves on social platforms of validation.

In this brief moment, the insight lies. The clashing dual imperial gaze screeching over each other generating a bright portal into a possible escape. A loophole. In a moment of sovereignty where the body becomes aware of the simulated liminality. The camera may just allow us to break the matrix. The exhibition space may be guiding us into a streamlined narrative and the camera click has the potential to create counter-narratives. I often walk the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven on my own. With a younger and colourful section melting into a white, bright, and older part of the building; I exercise subverting the gaze. I attempt to capture the emptiness of the liminality in this space.

The human tendency to create life and spontaneity is powerful. If only the body listens to whispers. The accessibility of the smartphone turns the camera into a personal image-making tool.

The majority of museums in India don’t allow photography. Or it is charged for a small fee. My first reaction is always, ‘thank God’. Because I can be fully present with all my senses. But on the other hand, I also miss the liberty to tell myself a different story other than the one witnessed by my body. It is a paradox, I am aware. Yet, something is thrilling about the idea that the photographs steal away from a place where nothing escapes. The objects and the paintings in the museums will rarely see the light of the day.

Each picture is different from the other, every corner captured with a blur. There are multiplicities of the same object. The cloud galleries and the hard drives become graveyards of this fragmented reality. This personal power facilitated by the camera is pushing the exhibition to decolonize its narrative. If the naked eye misses something, the camera remembers and it keeps a tight check on the museum. Leaving the audience to look back and question.

The journey of objects from the museum to the phone gallery is a journey from one non-place to another. The human body is tested on free will to escape from the colonial matrix of power (8). To finally be rooted back to the earth. Where dystopia can be reclaimed by the imagination. And understand that “The idea of a universal right to see is a fraud.” (9)

Bibliography

1. Kaplan, E. Ann. Looking For The Other: Feminism, Film & The Imperial Gaze. Routledge: London, 1997.

2. Tony Bennett. The Exhibitionary Complex. The Birth Of The Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Routledge 2007

3. Azoulay, Ariella. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Verso, 201

4. Kaur, B. (2023). My body is a walking exhibition. - Imperial Gaze and the act of exhibiting (1st ed.). Author.

5. Tichindeleanu, O. (2002). Elijah in Transylvania. The Non Imperial Technology of Seeing.

6. Jugalbandi (literally “tied together”), is an ancient Indian art form where two musicians with different instruments or styles perform together.

7. Tony Bennett. The Exhibitionary Complex. The Birth Of The Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Routledge 2007

8. Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On Decoloniality. Duke University Press

9. Azoulay, Ariella. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Verso, 201