interview

Re:Sounding

16

min read

"Het HEM presents potent questions, questions that wouldn't come up had we not been thinking about the space through sound, through our perception of it and the perception of the building’s original users"

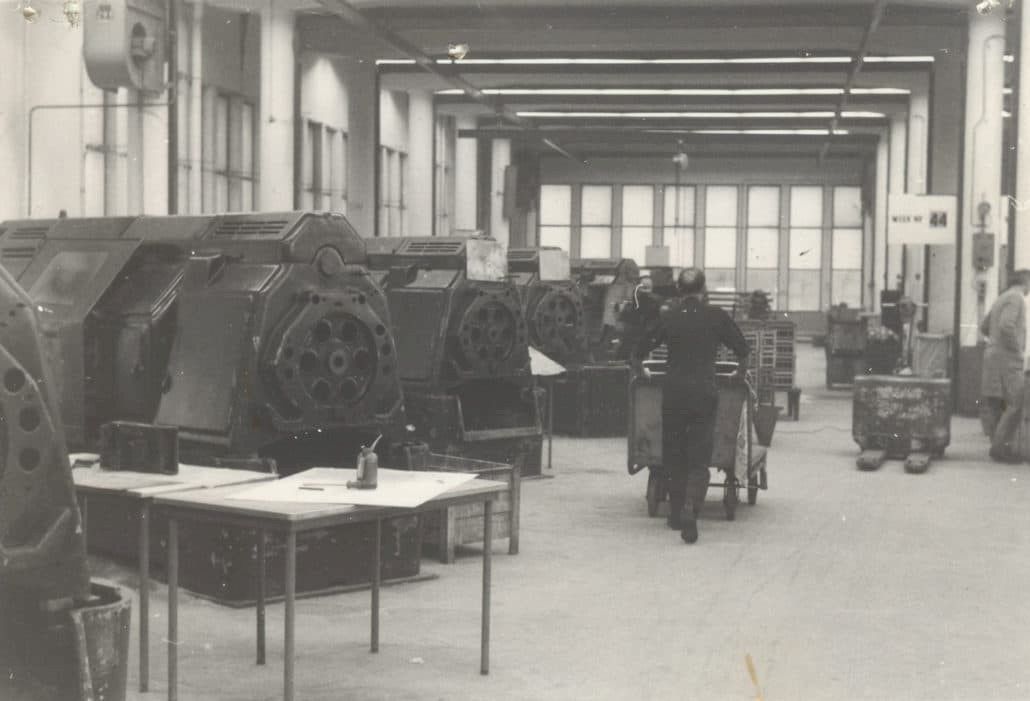

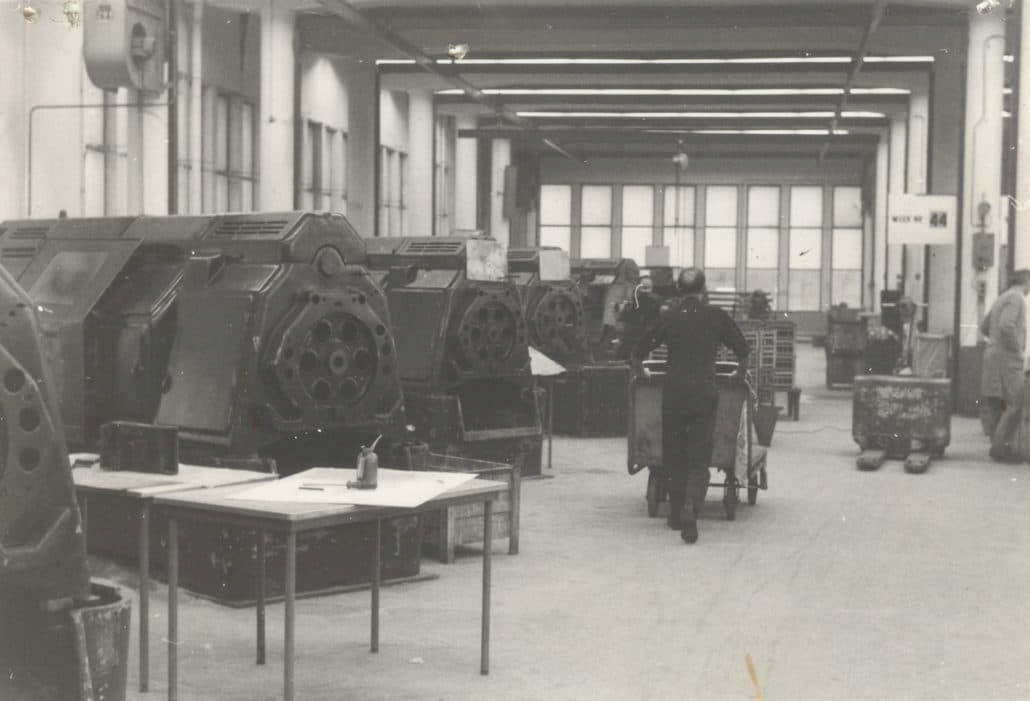

In 2022, researchers Pamela Jordan and Sergio González Cuervo brought their sonic archaeology project Re:Sounding to Het HEM, where they conducted field research into how acoustics are experienced in Het HEM’s building. Jordan, a doctoral candidate at University of Amsterdam in archaeology, has been part of Het HEM’s research into its past and present as a member of the Shock Forest Group, an interdisciplinary, open-ended research collective founded as part of our Chapter 2WO exhibition with Nicolás Jaar (2019). For the Re:Sounding project, Jordan and Cuervo, a filmmaker and sound designer, look at the way humans build (or don’t build) sound into their architecture. By recording analog sounds like clapping and popping balloons in various parts of the building, Jordan and Cuervo can start to reconstruct an understanding of how the history of an architectural space can resonate in its present. They propose that sound can actually become a tool for historical preservation if its use and power are properly understood in an architectural context.

In October 2022, Het HEM interviewed Jordan and Cuervo and published part of the interview on its website. In this part of the interview, Jordan and Cuervo expose how ‘psychoacoustics’ – the effect of sound on the mind – is an important part of investigating a building with a violent past like Het HEM’s. For instance, they considered actually shooting a gun in our shooting range in order to understand the effect of such a sound. They didn’t do it, partly because it brought up questions of the trauma that factory workers may have experienced from working in a very noisy building where an accident could mean a fatality.

As Het HEM adds a new dimension to itself in the form of a digital space, we are interested in the significance of the building and what it has meant for the generations of workers – both industrial and creative – who have passed through it. And during the building’s renovation, it is both interesting and important to recognize every aspect of its physical presence, including sound, in order to maintain that historic spatial experience that makes this building so special.

We are pleased to be able to publish more of this interview with Jordan and Cuervo, which raises questions about how sound can act as an agent for understanding an architectural space far beyond its present state. You can read another excerpt of the interview here.

Sergio González Cuervo: In a building like a church, the way that a sonic experience is connected to the building’s use and history is easy to understand if you consider how a person sitting in various parts of the church might experience the sermon given by a priest. In Het HEM, the relationships between the historic use of the building and the sonic experience are very interesting. Pamela and I are studying what humans often do unconsciously, which is make those connections.

Het HEM: Can you name a connection in the case of Het HEM? Are there certain points in the building where those connections appeared and helped make sense of the architecture itself?

SGC: Downstairs in Het HEM’s 200-meter-long shooting range, there are different distances marked along the tunnel where shooting targets used to be placed, which obviously changed the acoustics of the tunnel. We were fascinated by that possibility and kept those locations in mind when we were studying the delays produced within the tunnel.

Pamela Jordan: There’s an element of sleuthing, of tracing evidence that we see to acoustic effect. In the shooting range, there are probably thousands of bullet holes. Think about the differences between bullets hitting metal versus the ceiling or about ricochets at different distances. What kind of sounds would each bullet make, and how would they reverberate in the tunnel and the building?

For us, these interconnections are something to consider in all aspects. For instance, across time: what would it have been like for someone using the shooting ranges, and what’s it like now that they are out of use? And what was the effect of testing those bullets down there on the people who were upstairs on the factory floors, making them? The sound in Het HEM is interesting to study, in part because what we're studying is the potential of sound to be a messenger in a way that's quite unique. For example, even when the factory floors were full of the activity of producing bullets, there was always the absence of an explosion, an enormous, sudden sound that signifies disaster in many cases. This highlights the power of (relative) silence and the absence of sound: there was always the potential deterioration that would happen if something went wrong; the absence of an explosion didn’t necessarily mean one wouldn’t happen. Following these relationships further, we can go outside of the building to the entire terrain and examine the relationship the building had to the Shock Forest, for instance 1. The fact that ammunition was being manufactured and tested here meant that there was always the potential of detonation.

In our research, popping balloons approximates the sound of gunfire when placed in a context like the shooting range. When we’re talking about these impulse responses, there’s always this background: in some way we’re regenerating the explosion potential in these spaces. There’s an irony in testing sound in this way.

We definitely contended with the ethics of actually shooting a gun in the tunnel, but because of this interconnectedness between our use of the building now and what went on there in the past, there was no way to escape the ethical considerations.

In other words, Het HEM presents potent questions, questions that wouldn’t come up had we not been thinking about the space through sound, through our perception of it and the perception of the building’s original users. If we were to set off an explosion, even a benign one, in the tunnel, and you could hear that on the ground floor or the first, are we recreating something that never happened but could have and would have had such potency for people in that space?

Are we retracing a kind of historic relevance or value that can’t really be described in any other way?

"In Het HEM, the relationships between the historic use of the building and the sonic experience are very interesting"

HH: This is very interesting. Through your focus on sound, the presence of explosions may have been a constant stress factor for anyone working in the factory; that silence only exists through the potential of breaking it. The building itself is extremely permeable; sounds reverberate through the entire building. I suppose the shooting tests in the tunnel must have been a constant presence for anyone working inside. And I’m wondering, since you’ve been focusing on sound so much, do you know anything about the psychological and physiological effects of hearing gunshots or explosions? It is fascinating, because it exposes the potential power of sonic archaeology to find and complicate our assumptions about what people have historically experienced in certain contexts.

"Silence only exists through the potential of breaking it. The building itself is extremely permeable; sounds reverberate through the entire building"

PJ: Our hearing is very adaptive; we adapt to an environment very quickly through sound. You can suffer more hearing loss if you are listening for a sound in a silent environment than if you’re listening for it in a loud environment. If our ears are calibrated for a silent environment and suddenly, a gunshot goes off – there's no psychological protection from that. But there are ample studies done on the stressors of living next to a highway or an airfield. The constant stress of hearing that kind of noise can actually give you hypertension or other stress-related disorders.

During Chapter 2WO, Shock Forest Group conducted interviews with some of the original factory workers. From what I remember, we received some answers that we could not predict. There seemed to be general stress expressed with the work, certainly with the intensity of sound exposure (they recounted the factory giving them regular hearing exams). When we all moved to the factory floor to discuss the realities of working there, this was very clear. However, their impressions became more complicated to access when it came to the stress of explosives and weaponry manufacture. The demands of repeated daily toil (which one can adapt to quickly) combined with the male camaraderie of the group and the unified identity of the classified military status of working at the site, seemed to result in the workers being more ready to express feelings of solidarity and strength and fondness between them. This narrative dominated the conversation. Was it important not to show possible weakness? Did this unity, reinforced even decades later, push against any fear, cover it up with a laugh, or provide a public face to something they could not actually discuss, or which there was no perceived point in discussing? More structured interview techniques would be necessary to really trace the contours of their complex experience, the role that responsibility to colleague, family, and nation played here on both original perception and its management by each individual. And that's without factoring in the dynamics of memory and recounting it to a particular (art-focused) audience of the Shock Forest Group and Het HEM. What was relevant for me, as an outside researcher coming in long after the building’s active use, was the contrast between how I perceived the dynamics, and how the workers did. There is no one version, in the end, and only thinking through sound revealed this to me.

"What was relevant for me, as an outside researcher coming in long after the building’s active use, was the contrast between how I perceived the dynamics, and how the workers did"

HH: It would make sense that the camaraderie might obscure or reconstruct memories of distress, but it is interesting that hearing loss was measured by the employers. This stress from loud, constant noise makes sense. So don’t you think that this sense of danger wouldn’t have been present anymore, since the testing was confined to a tunnel or the Shock Forest, and was just part of the mechanics of this whole site?

SGC: I agree with you that there was no constant sense of danger. The stress generated by constant exposure to loud noise and a sense of danger are different issues, although they might depart from the same matter.

Pam explain it very well: nowadays we certainly know that constant exposure to loud noise is the reason for hearing loss, stress, cognitive impairment, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, etc.

At the same time, as you suggest, the sense of danger probably was not present, since the shooting tests were part of the mechanics of the whole site and took place in specific locations (factory workers were not actually at risk from explosions). Regarding their volume, the perception of gunshots was likely to happen within an already loud, industrial environment full of heavy machinery. The shots would not be perceived as loudly as if they had been happening in a quiet environment, such as a quiet forest.

When we are exposed to loud sounds, our brain tells our hearing system to prepare in order to protect itself, hopefully on time. The mechanisms in the middle ear, for example, will physically adjust to prevent the loud sound reaching the internal ear, which would potentially cause hearing loss. Still, our hearing might have time to recover afterwards if we are constantly exposed to certain lower decibel noise levels, or only occasionally experience loud sounds. If the exposure happens repeatedly over several months, or reaches certain levels, it will cause irreparable hearing loss.

HH: You’ve mentioned scale a few times, like you need a bigger impulse or a different tool to record or document space of a certain scale. But you also mentioned the wider context around the building in this case, the terrain, or the Shock Forest. We were wondering, could you also apply this idea of scale to a landscape or the sort of acoustics of not-human-built structures?

PJ: Yes, but it’s not done often. It is very challenging because the tools that we use are derived from and designed for indoor spaces. They aren’t used in outdoor environments very often because the complexity of the outdoors is exponentially greater due to the materials and interference sounds – and because you can’t control very much. Plus, it’s very difficult to replicate a natural environment to do multiple tests, which is what you need to confirm what you recorded the first time.

It is possible to study how humans could interact in that space via the landscape by using very similar tools to the ones we have used in Het HEM: using control sounds that we play multiple times and record from different locations, and which we then coordinate with architecture. It could work for an environment that has no architecture, but there are very few landscapes left that aren’t directly affected by human intervention in some way, whether that’s the impact we’ve had on animal populations, the weather in that location or harvesting of minerals or plants. Still, these tools can be used in any built landscape to understand how humans would perceive sound in that space and interact and use it to their advantage or not – both historically and in the present. I suppose you could do that for animals too, but you would have to calibrate your tools very differently.

HH: This question comes up in your dissertation research, Pam, can you tell us a little about that?

PJ: Broadly speaking, my dissertation approaches sound as an artefact, sonic dynamics as discoverable pathways of past experience that we (may) continue to retrace, and human perception of sound as the decoder ring. I’ve been using a mixture of methods based on my background as professional architect and heritage specialist; I also integrate psychoacoustics into the research by making binaural recordings of control sounds and then analyzing them according to human perception. This is an important distinction, because I can focus on human experience and all our adaptive qualities to hearing while not being distracted by small differences in frequency or intensity that the human ear usually cannot distinguish.

"I try to pull sound away from a fleeting, intangible, and individual experience into a comparative and reliable information source about the past built environment"

For my dissertation research, I apply this system to an ancient sanctuary to Zeus on the top of a mountain in Arcadia, Greece. Very little is known about how this site was experienced, what practices actually took place, what role the landscape played in the architecture, the site planning, etc. So I use my non-destructive sound-based methods (i.e. no digging) to better understand how the site could have functioned for ancient visitors and piece together the original planning logic of the architecture in the mountain. For instance, where did spectators of ancient rituals sit? If I were looking for privacy, where could I go? What are the sonic limits of the sanctuary (how far away can you perceive activity there)? If I were following ritual rites of washing before entering the sanctuary, what was the order of access dictated by the constructed fountains and landscape, and how much were those in the sanctuary aware of these activities? An important piece of the research has been an ethnographic sensitivity to current residents and users of the site, who still host athletic competitions there every 4 years and know the entire landscape more than I ever will.

HH: Sergio, as a sound designer, how does the work that you do with Re:Sounding come back into the practice of mixing sound professionally?

SGC: One of the main outcomes of our tests when studying the acoustics of a space is a collection of impulse responses. We use them in order to analyse, compare and also to recreate those acoustics digitally back in the studio.

When mixing sound for film, music or art installations, I may apply some of those impulse responses on particular sonic elements, voices or instruments, in order to change the perception of that same sound, now sounding as if placed within the acoustic space that the impulse response represents. This way, a voice recorded in the studio can be processed in order to sound, for example, as if recorded originally in the factory floor of Het HEM.

Maybe the most important thing I would emphasize, is that we do this research because it enables us to later, in post-production, reenact a different sound as if it came in from that location in the study. We decide on this on a position for the source of the sound, and we decide on a position for where we listen to that sound.

Going back to the example of the church: we have done similar research in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam. We looked at how we would experience a sermon in the times where the Oude Kerk was a Catholic church. After the Reformation, when it became a Protestant church, the priest spoke from different positions, and the listeners were also in different locations. This would certainly change the way sound was experienced in the same building, and it can tell us something about the cultural and psychological shift that occurred in the upheaval of the Reformation.

HH: It’s the same with Het HEM: the building was a factory, a place of constant noise and of very specific use. As it became a home for culture and the arts, the building hasn’t changed structurally, but sound is being produced in different ways and in different locations than it used to be. And perhaps this research could help us open up ways to play with sound in the space in the future.

1. The Shock Forest (Plofbos, in Dutch) is a forest planted by Artillerie-Inrichtingen (A.I.), the corporation that ran the Hem factory, in order to shield the factory terrain (both acoustically and visually).

This is an excerpt of an interview conducted by Orpheu de Jong and Rieke Vos at Het HEM in 2022.