interview

Sonic Séance

Leendert Sonnevelt

Leendert Sonnevelt is an Amsterdam-based writer, curator and stylist whose work criss-crosses the offroads of music, fashion and (youth) culture.

interview

'When you mourn, everything is included'

Asa Horvitz unearths the many layers of GHOST: his poignant performance project on death and its presence among the living.

13

min read

Invoking the spirits of Het HEM with Brian d’Souza

Can a physical space, from its construction and function to its history and ambiance, be translated into sound? For contemporary artist Brian d’Souza, the answer is a resounding ‘yeah, why not?’ Back in 2021, the artist created an acoustic experience that transported listeners from anywhere to Orford Ness, the idyllic British “island of secrets” known for its violent, war-laden history. Further developing this unique practice of transcribing space into (and through) sound, the past months saw d’Souza take up residence in another realm with an equally fraught past: Het HEM.

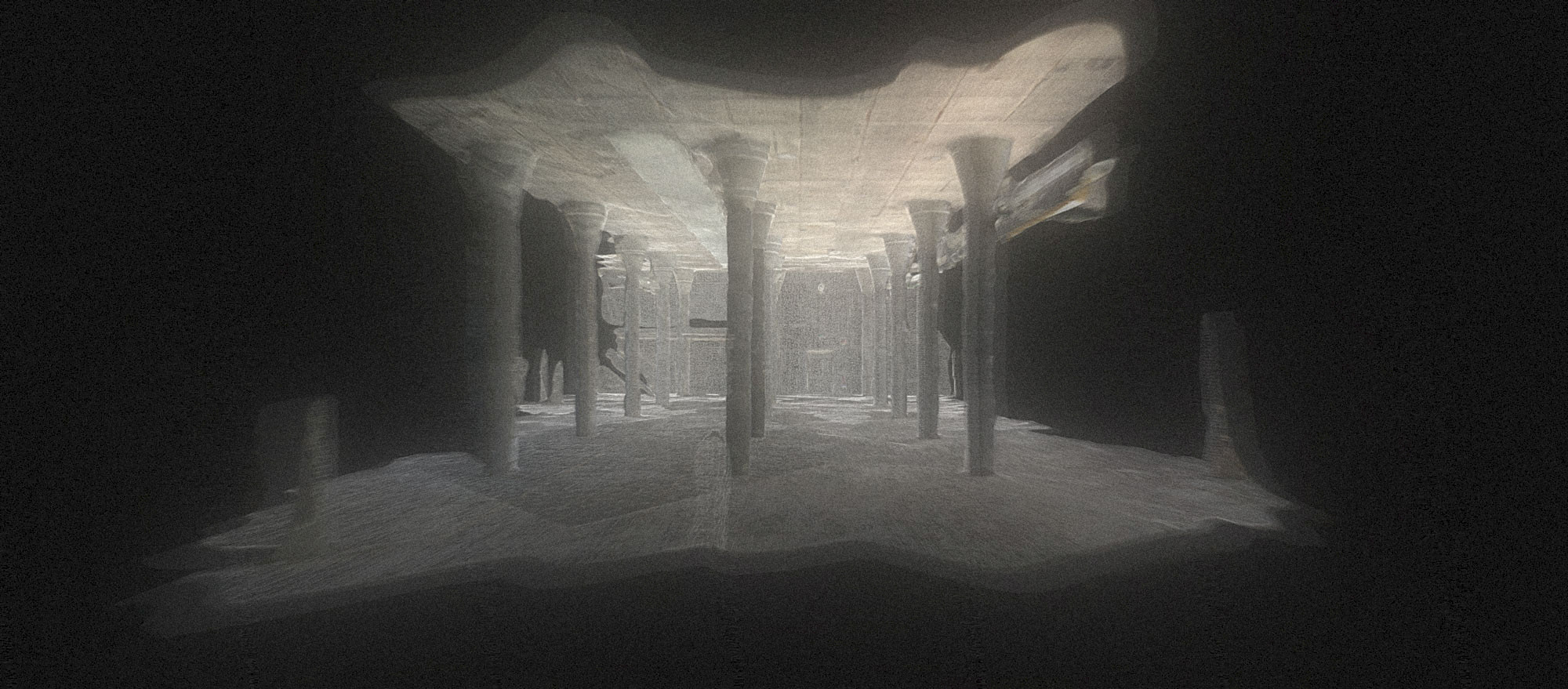

At Het HEM, the majestic industrial art space and former munition factory in Zaandam that’s currently closed for renovations, d’Souza not only listened to the desolate building and mapped its sonic architecture; he also answered to its calls, creating sound sources that converse with the bones of the building—and, beyond that, with the skeletons it houses. The result of this thorough creative process is Genius Loci: a virtual environment that invites you to enter Het HEM and, from wherever you are and at your own pace, encounter its spirits.

Before—or, may we suggest, after—you log onto Genius Loci and find yourself transported to Het HEM in all its delicate complexity and soothing noise, discover the story behind Brian d’Souza’s sonic seance here.

Leendert Sonnevelt: Hi Brian! I’d love to dive straight into the making of your incredible artwork for Het HEM and The Couch and the thought that went into it. I wonder, however, shouldn’t this project be experienced without reading too much about it beforehand?

Brian d’Souza: Well, I guess it’s all about layers. There’s the top-line layer where people can make their own call and not have any information on it. As you’ve seen on the website, it’s pretty sparse in terms of information that you get; there’s literally one line of text and a few options to choose from. It’s all about letting people use their own intuition to figure things out—hopefully that’s easy and accessible enough. But then there is another layer, as with all art projects, where you want to dig a bit deeper and explore the process.

LS: Alright, then let’s dig deeper, but a question about you first. You wear a lot of professional hats and people have described your practice in all kinds of ways. As an artist, how would you like to be introduced?

BdS: It’s difficult to put names to things! [Laughs] I see myself as a creative person who works with sound and music as my core discipline. I’m currently in a transitional phase; over the last few years I’ve been doing more projects that would be cast as sound art. Being a “sound artist” would be a good fit, but at the same time I’m still doing what I’ve always done: being a producer and a DJ. For the purpose of this project, I think sound artist is probably right.

LS: Let’s go back to the birth of Genius Loci. What was the initial question you got from the curatorial team at Het HEM?

BdS: They’d seen my previous project, beacon.black, which was commissioned by Artangel (they do art in unusual places). I went to a place called Orford Ness, which has a long military history. It was called “the island of secrets”; it had a function in both world wars, and in the Cold War the Americans had a base there to test bombs and radar—things like that. For this project I used contact microphones to pick up different sounds of the landscape, which I turned into musical compositions that were broadcast, 24/7, in a radio-style format. With Het HEM, there’s a similar historical angle, as Het HEM’s building and terrain was previously used for creating weaponry and testing munitions. So the curatorial team asked me to come over as an artist in residence, to figure out how some of the thinking behind beacon.black could be translated to Het HEM.

LS: What happened next?

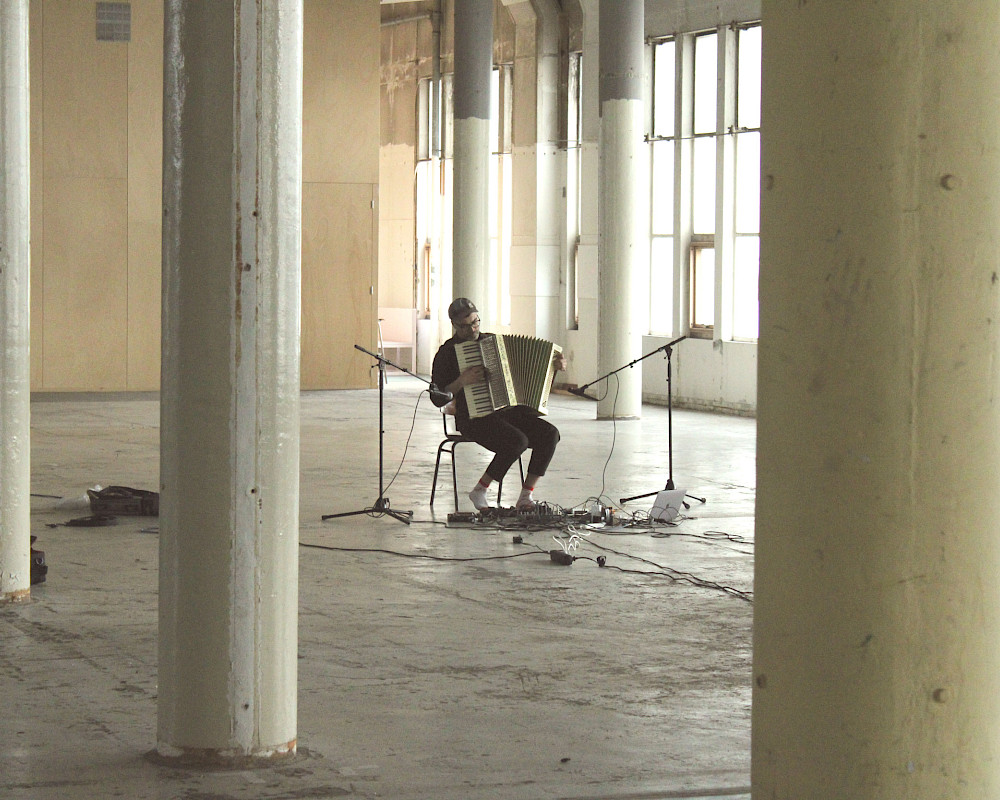

BdS: My initial thought was to go with these contact microphones and apply the same kind of methodology, recording the sounds of the building. But when I entered Het HEM, it was very quiet—there was literally nothing going on. I asked myself: how does sound create a narrative around this building? And how can we capture the sound of the space not only in its present form, but also the historical site and its ghosts? That’s where the concept of Genius Loci was born. It means ‘the spirit of a place’, referencing a concept from Roman times that lots of different cultures have incorporated. It’s got slightly religious or spiritual connotations, with the gods or spirits of a place being in charge or blessing/cursing it. In recent years, the idea has become more secular. I look at it like this: every place you enter is different in terms of acoustics, but do you think about the impact of the acoustics on how you feel? There are different emotions when you go into different spaces. Today, most of us approach things visually —we’ll look at visual cues and interior design— but actually, sound has as much (or more) of an impact on the way that we think or feel. When I figured out there was very little human-made sound within Het HEM while it’s closed, I had to find a way of telling that story, to find the sprits of the space. And so I used an instrument —the accordion— as a sound source.

LS: Why the accordion?

BdS: Well, mainly because I asked the team at Het HEM: what are the more traditional instruments of The Netherlands? But I loved the accordion already!

LS: In the past, but maybe also in the present, was there a moral aspect attached to the Genius Loci idea?

BdS: Yes, the concept I came up with speaks to what you just said, to that morality and the idea of a seance —or perhaps even a kind of exorcism where you get rid of evil spirits that have made their way into a system. There’s absolutely a moral aspect to Het HEM’s original function, which was to build weaponry. For whatever purposes those weapons or munitions were used, there are certainly victims of what was produced in that building over the years.

LS: You mentioned already that many factors define our impressions of a space, especially the first time we enter it. Had you been to Het HEM before this project? What was your first impression?

BdS: I hadn’t been to Het HEM but I knew of it; then this year I visited twice. I love these old industrial spaces—the vastness of the buildings is exciting! Getting to experience the site firsthand, especially in January when it was very quiet and cold with nobody around, was pretty special. I lived in the on-site residency apartment, so I got a direct experience of this big empty building. For a couple of days, it was just me in the space… I took a lot from that.

LS: I think most people haven’t experienced Het HEM in that way. Whenever I’ve visited, it’s always been for an exhibition, event or even a concert.

BdS: Exactly. And it’s an interesting location with everything else around it, like the Shock Forest (1) and the river. A bit eerie and spooky, too…

LS: Let’s enter your virtual realm for a moment. When you log on and haven’t chosen a space yet—before your accordion pieces come in—what’s the first sound you hear?

BdS: Ah, that’s a field recording I made in Het HEM’s subterranean basement, the shooting range. I was using contact microphones, which pick up sound when they come into contact with physical objects. Having a contact microphone there, you could hear very subtle noises (like wind and rain) coming from outside, the rotting and rusty bits and pieces in the space, and the building itself rattling around. This is what the building sounds like with no human-made noise.

LS: Next, you can enter the different spaces and your accordion compositions gently appear. They are your own improvisations, but I understand they also have an AI aspect?

BdS: Yes, first I did improvised performances and we recorded those in the spaces. I made four different pieces, which you can now hear in the four [virtual] spaces. I’d also been working on a slightly different project with University of the Arts London; they have a research project called ‘MIMIC’, which specialises in building AI programs that incorporate music. We’d been building a generative AI program with them that could allow the delivery of compositions to be elastic, personalised and adaptive. We still haven’t finished this project, but one of the key parameters of it is being able to adjust the duration of time. In Genius Loci, you can set the time that you want to listen to the piece and then the program will deliver the piece as a four-, seven-or ten-minute piece. They all have the same narrative structure, but you can play them over a longer or shorter period of time. To be able to have a song where you can adjust the time was the first idea of this generative technology in a live scenario. It was cool to incorporate that.

LS: A confession… when I first entered your work, I immediately went for the short versions, simply because I was having a busy day (but then I also felt a bit guilty).

BdS: [Laughs] I wish we could actually track people’s time choices, that would be a great experiment. You know, I’m interested in that utility of music and its functional value. We listen to music for many different reasons —to keep us occupied while cooking, running, driving et cetera— and not just for pleasure. Most people would probably go for the short version, you know; ‘Why would I invest ten minutes if I can listen to four minutes?’. Something I’m also very interested in is the practice of being active listeners —that’s an art form, almost, that people have lost. We listen passively for all the reasons I just mentioned: in those situations, music still has an effect on us, but we don’t get the same level of enjoyment or appreciation. My take on it is that when the listener becomes an active participant, even in the simple terms of setting the time duration, it encourages them to be more active or mindful.

LS: True! At the same time, I was thinking about the way ambient music can transport you to another place or mindset. I’m not sure if you’d classify your music as ambient, but how does that work for site-specific music? Would you like to prevent that from happening or is there no way to stop that?

BdS: Right, that’s a very interesting question. I don’t think there’s a way to stop that – that’s actually a beautiful thing in many ways. When you listen to any piece of music, ambient or otherwise, it’s going to have an effect on your brain. That’s what’s amazing about music: it does so many different things to us as human beings; it triggers memory, movement, emotion—all at the same time. With this piece, if it gives someone an insight into Het HEM, that’s great. If it transports them into another realm of their consciousness, that’s also fantastic. In fact, that’s the power of music. My pieces are composed in different ways; ‘EXPO’ is very floaty because it’s bright and has lots of windows, but then ‘Shooting Range’ is really dark and slightly claustrophobic, perhaps even ominous. Hopefully the narratives within these pieces embody the space they were created in. My question was: What does this space sound like? That’s the artistic point of view in my improv pieces. Of course there’s a level of personalisation where you can change the duration, but the pieces are always going to tell the same story.

LS: Aside from the sound, we haven’t touched on the visuals yet. I read them as a skeleton of the building, but they also have this very ethereal and otherworldly quality. How were they created?

BdS: Het HEM commissioned Simon Dirks, an artistic programmer based in Utrecht, to come up with the visuals. He first listened to early versions of my pieces and then we had a chat. He went around Het HEM and mapped the different spaces using LiDAR [Light Detection And Ranging] which created the grainy texture that you see. It’s all very monochromatic. Simon’s LiDAR idea was a good fit because it really relates to the sound aspect; it’s almost like you can see the incredibly fine textures that you don’t pick up with the naked eye when you’re there. It gives you another dimension to think about.

LS: The very first thing I read about Genius Loci is this: ‘The pieces don’t ask much of the viewer, just to be present is enough’. Yet everyone’s going to experience this project in their own space—well, on their own couch. How do you hope people will go through it?

BdS: Part of the experience of going to Het HEM, normally, is experiencing the building—whether people think about that or not. Since you cannot visit the building now, I wanted to bring the building to you. That’s what Genius Loci is; you can go into a virtual space to see and hear the building. It captures a specific point in the building’s existence: because the building is being insulated, the acoustics will change. Genius Loci is a snapshot, a unique historical stamp, of a place that will never sound the same again. This is the building as it was found right after being a functioning factory for ammunitions and weaponry. This midpoint represents a cleansing, too, before Het Hem starts functioning as a physical art space again.

LS: Do you feel like you successfully captured Het HEM’s genius loci?

BdS: I’d like to think so! I think the accordion has such a rich sound. As soon as I took it into the different spaces, I’d play it as long as my arms could stretch. I’m not an accordion player, so I was very much thinking of this instrument as a sound source, but I immediately felt it was the right choice. There was this two-way communication, with the reverb and resonance feeding back to me. I was speaking to the building and the building was speaking back to me, which is really cool. If you want to call that a dialogue with the ghosts of the space, that’s quite a beautiful way of thinking about it. So, yeah, why not?

(1) The Shock Forest (or plofbos) is the forest on the Hembrugterrein, which was planted to shield Zaandam residents from both the noise and the knowledge of the weapons testing that was being done there.