interview

Terrestrial Technologies: An Interview with Patricia Domínguez

Mirla Klijn

Mirla Klijn is a writer, documentary maker and researcher. She is the co-founder of Valley of the Possible, a refuge for Art & Research in the Chilean Andes which offers time and space for artistic and scientific research whilst exploring new narratives on the relation between man and the rest of the natural world.

Emma Llorente Palacio

fiction

The World Lasts 3 Hours

"She just gave me access to terrestrial intelligence. My vagina is the key, I thought."

19

min read

How plant intelligence can open portals to other information, magical thinking as a tool for dealing with ecological grief and the (im)possibilities of combining the realm of the sacred with the corporate system.

Chilean artist, educator and advocate of the living Patricia Domínguez merges socio-political and economic matters with mysticism and ancient botanical knowledge. She assembles her video installations, sculptures, watercolours and texts into highly symbolic and futuristic totems, through which she explores our relationship with plants in the context of colonial extractivism. Rooted in her experience of growing up in Chile and her perception of the country as a laboratory of neoliberalism, Domínguez’ installations visualise the impact of late capitalism on our bodies, weaving personal memories through technologies of planetary healing rituals.

These ancestral spiritual and healing practices form an important part of her daily work as a student (or tool, as she likes to see it) serving the intelligence and healing power of plants. In recent years, her multidisciplinary and collaborative approach has led her to create works in partnership with scientific institutions such as the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN), learning about quantum physics, as well as with a plant healer in Peru.She also runs an experimental platform called Studio Vegetalista which produces new research on ethnobotany through essays, publications and a school.

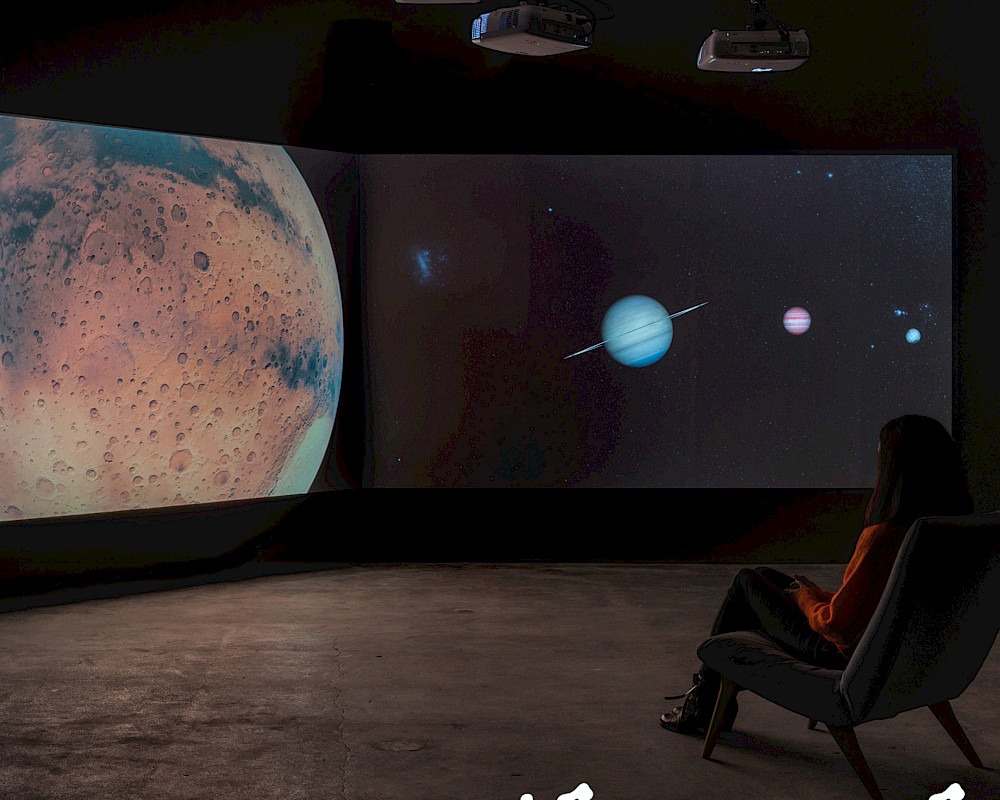

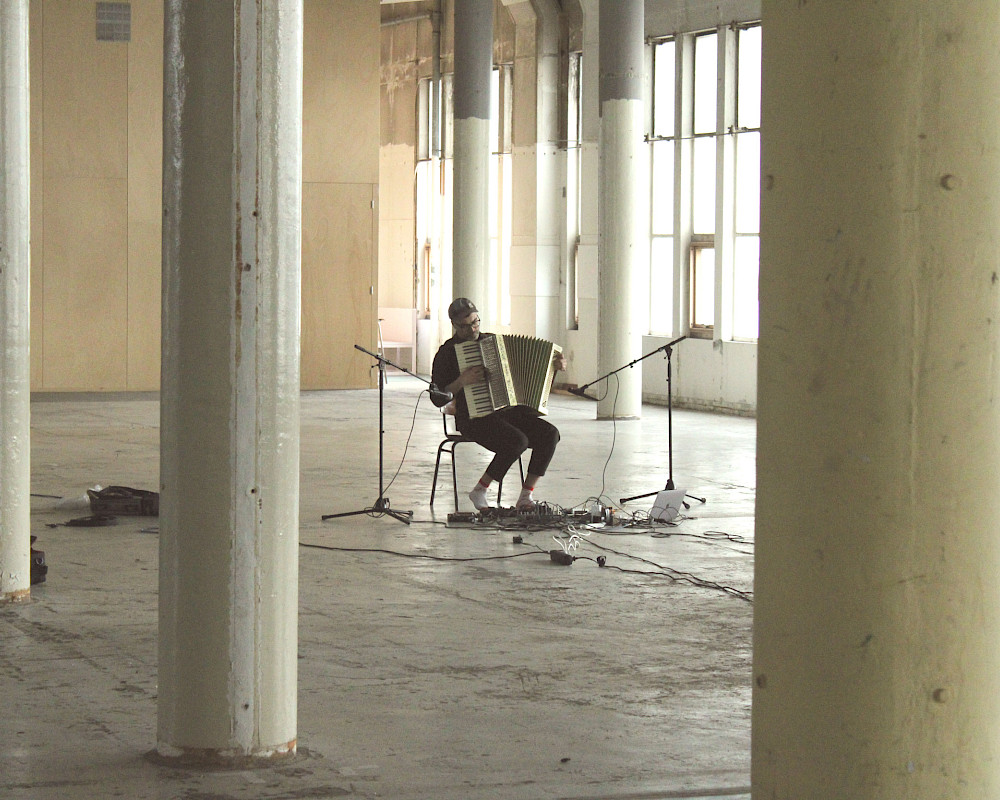

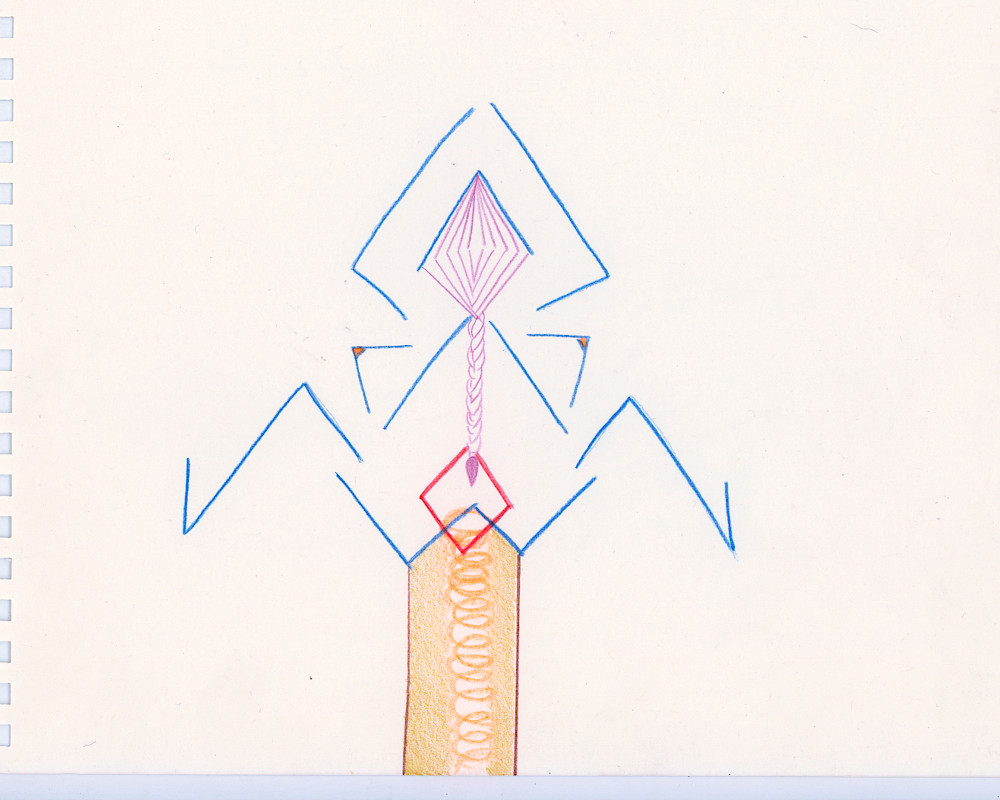

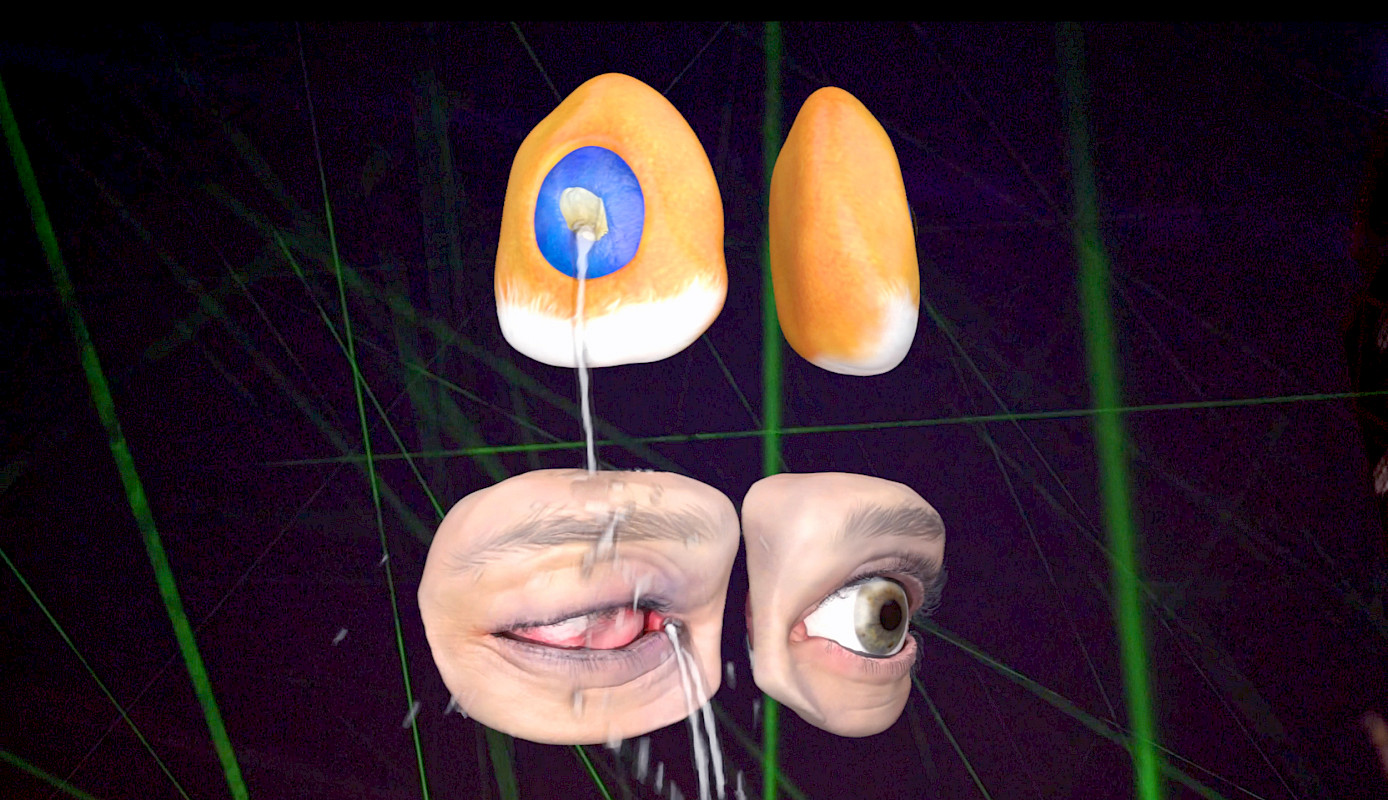

In this conversation with Mirla Klijn, Patricia takes us on a personal journey through her childhood, the (re)discovery of magic, plants intelligence and healing powers, exploring our own organic and earth-based technology, living in a sacrifice zone and art as medicine. Woven throughout are images and descriptions of her work: Matrix Vegetal (2021-22), The Ballad of Dry Mermaids (2020), Madre Drone (2019-20) and Eyes of Plants (2019).

You can read The World Lasts 3 Hours, a short story by Patricia Domínguez here on The Couch.

On The Legacy Of Several Ancestral Obsessions

Mirla: I’m very interested in the role of ancestry influencing who we are (becoming). Something that seems also very present in your practice. Can you share a bit about how you see your childhood experiences assemble in your work today?

Patricia: I grew up in a traditional Catholic Chilean family; my school was almost like a Catholic sect, so my world was very limited. But I had a grandmother who was a yoga teacher. She had a little shrine in her closet, and every Sunday I would come and sit there to listen to all the Indian chants from the maestros, like Yoganda and Babaji (Indian yogis and gurus). She told me how to breathe – pranayama – and how to ask plants permission before harvesting them. She was the first one that showed me a more compassionate spiritual practice beyond my Catholic experience of spirituality. The practice of sitting down before a shrine, anchoring in this portal to something invisible, really influenced my life and work. I still have a shrine practice that has been transforming and growing ever since.

And then there was my grandfather, an architect and amateur archaeologist. He discovered a place in the Atacama Desert in Northern Chile where he went every year and dug into the land, changing the landscape and tracing its history. He discovered so many things, like the fossil of a 13-million-year-old whale, the only one of that species ever found. Just by carefully looking, he discovered the southernmost colony of green turtles in the planet. He found colonial objects, Indigenous artefacts, leftovers from English mining, industrial garbage, etc. With all these objects he started recreating the history of that place, but in an abstract, playful way. For instance, he built pirate ships from garbage, and created beautiful geometrical mobiles and ovens with all the little shells he found. He would, in a very personal gesture, consume the history of the land, transforming it with humour. He organised his discoveries in a self-made museum he called Museo de las Gaviotas (the Museum of Seagulls).

This playfulness, the fact that everything was eligible for ‘collecting’ in the museum – toys, garbage, a Jarro Pato (an Indigenous Diaguita Vase that cries) – was very inspiring to me. I grew up going to the desert all my life, a breath of fresh air from my life in Santiago. We ended up defending that place from the biggest coal powerplant in South America, because of the endangered species of turtles that lived there. That’s how we all became activists in 2010.

My grandfather was also my first introduction to Indigenous cosmologies (of course, still from a totally colonial perspective). I have been working with the Jarro Pato, which to me is the most beautiful and metaphoric object, and from where a whole other myth of crying (1) (South American crying) emerged in my work.

This vase has literally seen me growing up: we were always looking at each other from the cabinet in the house since I was born. When I learned to channel, I wanted to channel the Jarro Pato. And for one second, we kind of shifted perspectives and I was able to observe myself from that side of the room. Certain objects have been my way of acknowledging colonial relationships; what kind of position I can occupy. But they were also my entry point of relating to those cosmologies.

On The (Re)connection With The Universe Of Magic

Mirla: When we are young, it’s natural to connect with the wonder and magic of life. Can you tell me what your memories are?

Patricia: When I was young, I would just open my eyes and see a procession of light-beings passing by. I felt it was very normal, but it stopped at some point. My biggest reconnection to the universe of magic was when I was 26 and I did Ayahuasca. That immersion in the vegetable universe erased a lot of my cultural programming and allowed me to open up again. All the cultural limitations – what was possible and what not – were completely transformed, erased and updated through this connection with the vegetal. This experience was so strong that I always bring it to the conversation because it’s a bridge that you cross. After it, life is never the same again. It reactivated a lot of dreams, creativity and non-verbal language. I feel magic is a lot about that, how do you align with other non-human beings in order to expand your possibilities of moving energy or seeing the future.

Mirla: You needed to learn through experiential learning, instead of only consuming it on an abstract level.

Patricia: Yes, the first time I learned about the healing properties of plants, my teacher, a woman, said: “Put that notebook away. Go and meditate right now.” She brought us directly to the experience of techniques and meditations, no theory. That was her way of teaching. I became so curious that I started learning how to heal people with vibrational medicine. I didn’t know that I had that ability myself, but I wanted to understand what happens.

About Protecting Planetary Memory And What Is Left Behind With AI

Mirla: I’m wondering if it could be interesting to see what happens when we can feed AI with plant intelligence and indigenous cosmology, instead of only human rationality – which is still very much dominated by Eurocentrism – to see what comes out if it?

Patricia: I love what you say about plants or other intelligence feeding AI. Because for example plants, they know how to live in solidarity, the know how to share, they know how to align us and heal us. They are so powerful. So for example, how do we imagine technology for helping the planet or healing ourselves? Now money is basically orchestrating everything. It’s very important to see what is being left behind here. I want to protect the planetary memory, something that cannot be digitalised.

When I was at CERN [doing a residency], I had the opportunity to interview the scientists working there. We were asking them about AI. They said they use it as computation system and it’s definitely amazing, but it will never replace human creativity, the human capacity to connect with mistakes. The question is how do we become more creative and expand our capabilities (and not just those of the machine)? AI will more than anything test our own creativity levels, I think. And then we can feed AI, with less prejudice but as a multispecies group.

Mirla: I guess the capacity of our communications, through technology and AI, still mostly reflects our conscious and unconscious minds and the limitations we have.

Patricia: It’s pretty amazing and interesting to see where we are going with AI, but I’m really committed and dedicated to give my attention to our own organic intelligence. Because I know there’s people that can do these kinds of things, like telepathy or connect to this place beyond time and space where the information is. So, should we dwell on this digital realm, or should we give our attention to our own technology? I ask myself: Which intelligence is more interesting: AI or life/terrestrial intelligence? How can we decodify the intelligence that we have here?

On Terrestrial Intelligence

Mirla: Speaking about terrestrial intelligence, can you tell me about your connection with plants?

Patricia: I usually connect more on a spiritual level with plants, asking how I can be an ally to them.

On a biological level, plants share their resources and have enormous underground networks [of roots and mycelium]. I feel they can open our human consciousness in a way, though I don’t exactly know how yet. Plants help me activate my neurons and my capacity of understanding, of inventing new things or new thoughts. My alliance with plants has helped me broaden my cosmological sensors of reality. This connection is so deep that it feels like I myself have become an ecological tool for them.

Mirla: Why did you feel you needed to broaden your cosmological sensors of reality?

Patricia: Being an activist is important but exhausting , it takes a lot from you. So, at one point I collapsed and felt I needed to drink from another well and dwell in other kinds of propositions (on how to live, or live the future). I needed new information, to learn from plant intelligence (2). I contacted Amador Aniceto, a curandero (3) ** I met years ago when I was studying the healing powers of roses. He told me then; “if you ever want to learn more, I will teach you.” And I told him, well I’m not Indigenous, I’m a mixed-white woman… But he said, “the earth doesn’t see colours, it just feels offerings. It just sees and feels what you do with your life, beyond colour or appearance.” Five years later I contacted him again and spent one month with him.

He taught me how to detach from all the digital craziness, how to live with no internet and get to a point of silence. Only then can you be cleansed and start learning from plants. I’m so grateful because it taught me how to live my life really, how to clean myself in order to make sense of what we are doing.

Mirla: There’s a clear role for storytelling and mythmaking in healing practices, especially when we can acknowledge plants as technology.

Patricia: Yes, and that’s what’s so interesting. But in our Western culture we probably do need a more scientific counterpart, like a science-based confirmation that something is true. Validating something our hearts know already, with scientific data, helps to calm the mind. At least while we still have this Western dominated worldview, where facts rule the world.

For example: a rose is the highest vibrating plant in the universe, with a vibrational frequency of 320 MHz (which is as high as it gets in terms of flowers). That’s why a rose is also a technology, as it’s often used for forgiveness or funerals. Even if we don’t know it, we somehow feel it has this higher vibration and can help us with these rituals. (4) Plants just know how to heal us. The active principle (5) of medicinal plants knows where to go in your body and heal it. That’s how smart they can be.

On Corporate Wellness And Cultural Appropriation

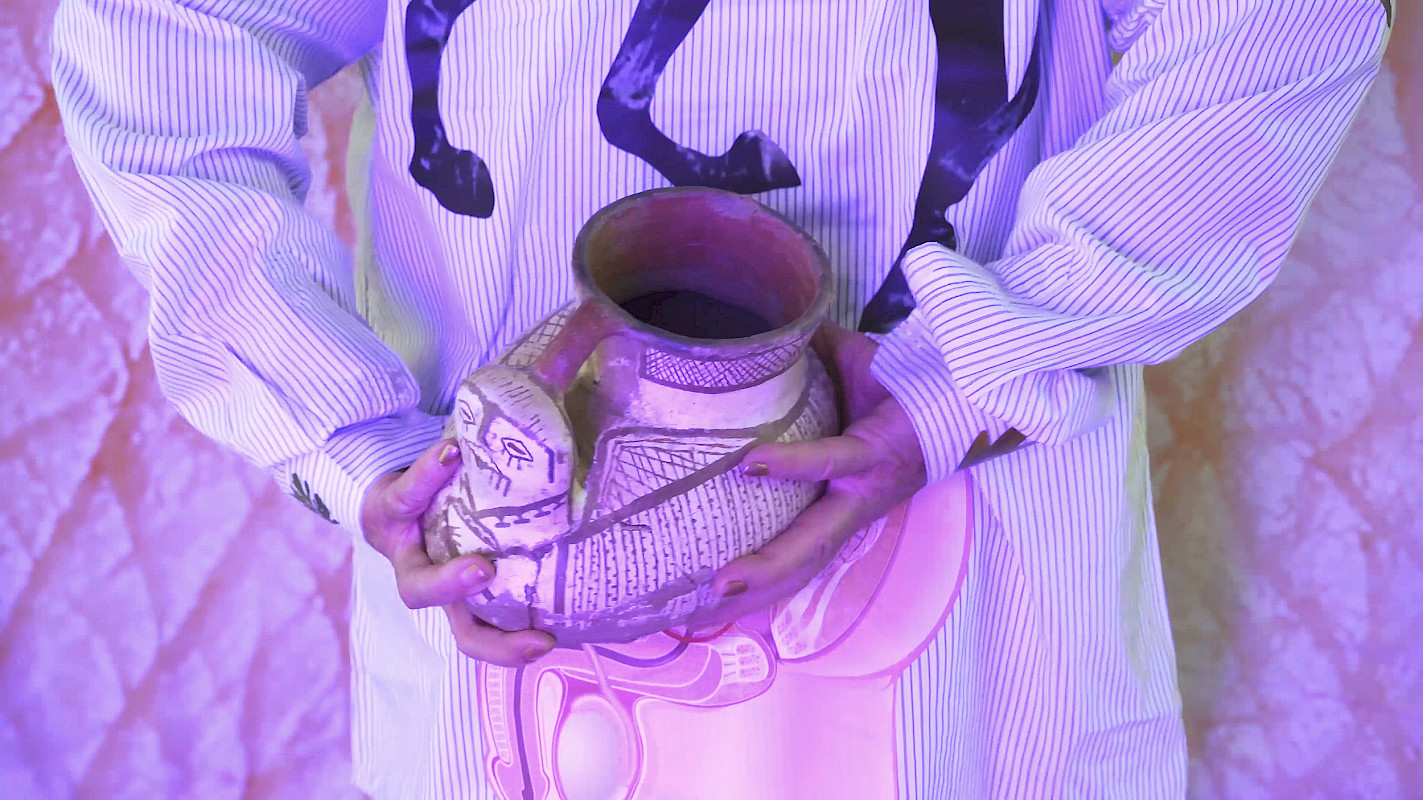

Mirla: The entanglement and appropriation of healing practices in centres of global finance also led you to make Eyes of Plants, where you critique the corporate wellness capitalism. How did your grandfather’s Jarro Pato end up in the work?

Patricia: I went to Canary Wharf in London. It’s a financial island, a whole corporate world. Even the art was just an analysis of what went on in the stock markets (prices going up or down) or cosmic symbols of centaurs. And then I realized there were quite a few healing centres as well, mostly underground and totally hidden. These people are working 24/7, following this system of production. Of course, their bodies get sick of being in the corporate world, so they have to go underground to heal which is very symbolic to me. If you look beyond their corporate functionality, these bodies are all going to the Earth to be repaired from damage by a system that never stops. (And ‘them’ is all of us: we all have backpain from sitting behind the computer and eyes tired by screens).

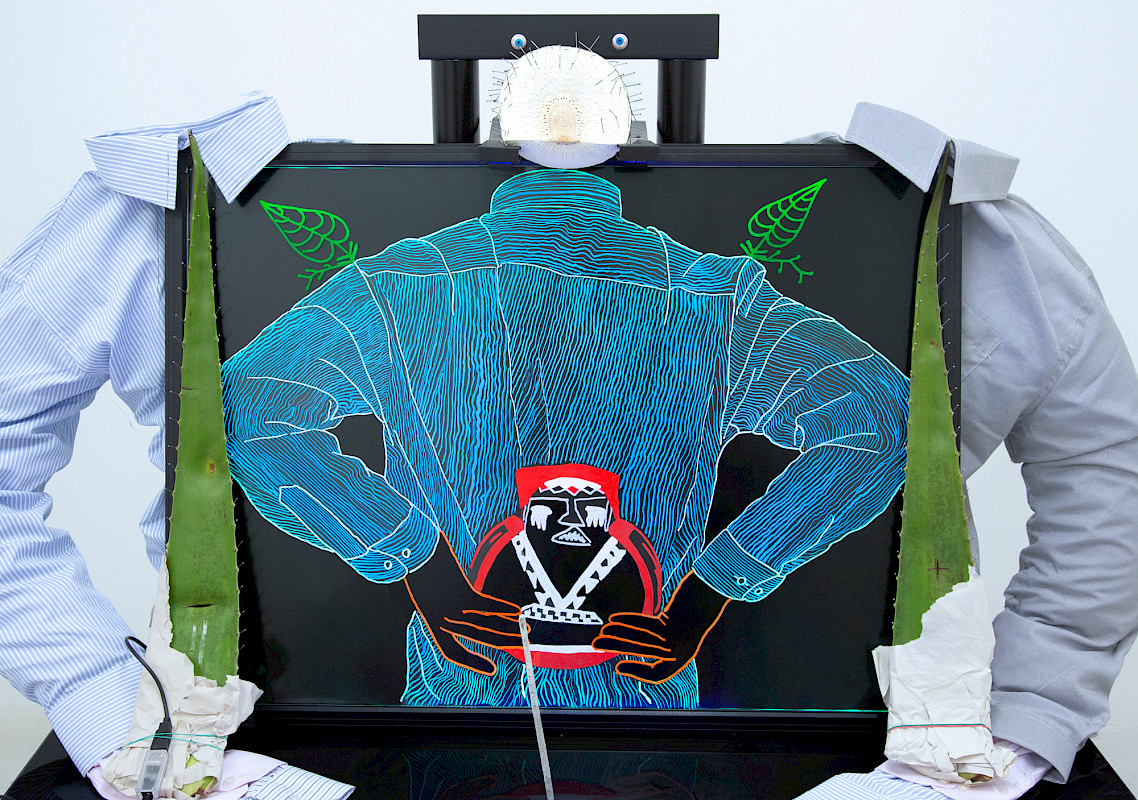

After that I had a dream where all these corporate people with their striped shirts were rubbing their bones with the Jarro Pato, the Indigenous vase, that was healing and helping remind them that there were once other ways of dealing with time and the earth. In my dream, the patterns of the vase jumped into the patterns of the shirt, and it showed me that these are the patterns of our identity.

Mirla: How do you maintain a decolonial approach when working with Indigenous knowledge and ancestral healing practices?

Patricia: My work is a personal ritual to survive in this system, so I usually work with things I have problems with.(6) For example, I see yoga props, blocks and mats as plastic, shamanistic objects that are very much part of a system. Of course, they are also for healing, but a lot of suffering and damage is placed upon people who are the original holders of that knowledge. I work with a few Indigenous teachers, whom I honour, and they are all dedicated to healing people. My teachers help me to continuously rethink everything, reality, our tools, my art. It’s a continuous process of learning.

And it’s also about the decolonisation of imagination. I meditate every day for a long time. I am in an evolving relation with different plants that helps me connect to their guidance: I don’t only consume them, but care for them, drink them as tea, dream with them under my pillow. There are images of them all over my home. In my case, the learning is very personal and very private because I’m there to heal myself too, but I also inhabit that space of contradiction – I have a yoga block as well.

Mirla: We are all part of this system and thus complicit.

Patricia: Yes, we are, and I think it’s important to create new techniques, to identify the sacred within the system. How do healing energies arise in or permeate what we see as the system?

Some questions I try to ask are: how do I use my phone to heal myself? how do I transform a cosmetic mask into a healing mask in order to see as a plant? You can still use the technology, but in a way that changes the result. It doesn’t have to be what we think of as spirituality or wellness; it can transform and can go beyond our prejudice. Technology is only a material form. The healing energies are the same, but if we change the form, the materialisation changes too.

Mirla: It’s more a practice of making things sacred again. In Western society there’s not a lot of time and space for that. Do you propose a kind of a counter-system practice with objects that symbolise this paradigm?

Patricia: Yes! A shrine can be made of many objects. Whatever you move in the invisible realm needs a material counterpart, but that can be anything. If you transfer the intention of the energy into the material object, it can even be a USB cable. It doesn’t matter.

That’s why I think we should all invent our own healing techniques. We love reiki and yoga but there are so many other ways that could be truer to yourself or to your reality. Why do we have to keep copying these things until they are deprived of all their meaning?

Mirla: It makes me think of Machis (Mapuche shamans) or healers from other cultures, who are often very against recording a healing ritual and appropriating it, because it’s always related to a specific context. If you take it out of that specific time and place, it loses its value.

Patricia: That’s beautiful. It’s what Machi Millaray Huichalaf (7) also told me; she sings in relationship to plants; she sings in alliance with all the beings to help cure a person. She thinks with the Earth and the water.

On Activism And Art

Mirla: You live in Puchuncaví, near Quintero, located in the mega-drought area near Petorca. A sacrifice zone, even dubbed the Chilean Chernobyl. How do you deal with that?

Patricia: It’s only 9 kilometers away from my home and it’s insanity. The land has 20% more arsenic than what is officially allowed, it’s extremely polluted. It’s so deeply frustrating and toxic.

There are peaks of arsenic that are totally out of the norm. When those peaks happen, everyone gets sick and everything is affected, especially kids and older people. I see so much devastation here. How do you not get bitter and sad and frustrated? The only way for me to deal with this – apart from activism and educating – is applying magical thinking to not get a sad heart from all this ecological grief. Trying to change things in real politics takes too long and is too frustrating. For me, art is my medicine. It’s my way of organising what I see in a symbolic way and even that is healing.

Mirla: There are not enough roses in the world to heal that place… Sometimes I think about those zones as examples of what will happen in the rest of the world eventually if we keep going like this.

Patricia: Exactly, they are like accelerator laboratories of contested zones, where you have sickness, dryness, tears and frustration. In Petorca all these women (8) said there is not enough water to have tears, have sex or give birth. They are becoming cyborgs of dryness and the place is a planetary laboratory.

Mirla: Art as medicine and art as activism. How else can art help us digest the world or encourage a more magical future?

Patricia: Sometimes, you need to go into the street and be an activist, but in the long term, I believe art will be more useful. In politics everything is proper and ethical, but it leaves no room for fiction, humour, openness. But in art, it’s like a dream where you can combine everything. I participate but I also want to build my sci-fi vegetable world and invite you there.

In my work I see art as a stomach. I consume all the experiences that I have and digest and transform it, so it basically recodes reality for me. All the shrines that I make honour planetary memory. It helps us gain other perceptions and move beyond the system that we have now, which is of course so limited with our focus on power and money.

I noticed that one of the scientists at CERN had Buddhist flags in his office and asked him what he thinks about Buddhism and meditation. He told me, “Well, Buddhists know how to reach this dimension of your brain where all information is beyond time and space. But they can’t explain it through our conventional language. We are just trying to confirm the same knowledge through science.”

The possibility of magic exists in our reality even though it’s not common or the norm. Magic in the end is tapping into how our existing reality works, no matter how small the chances are.

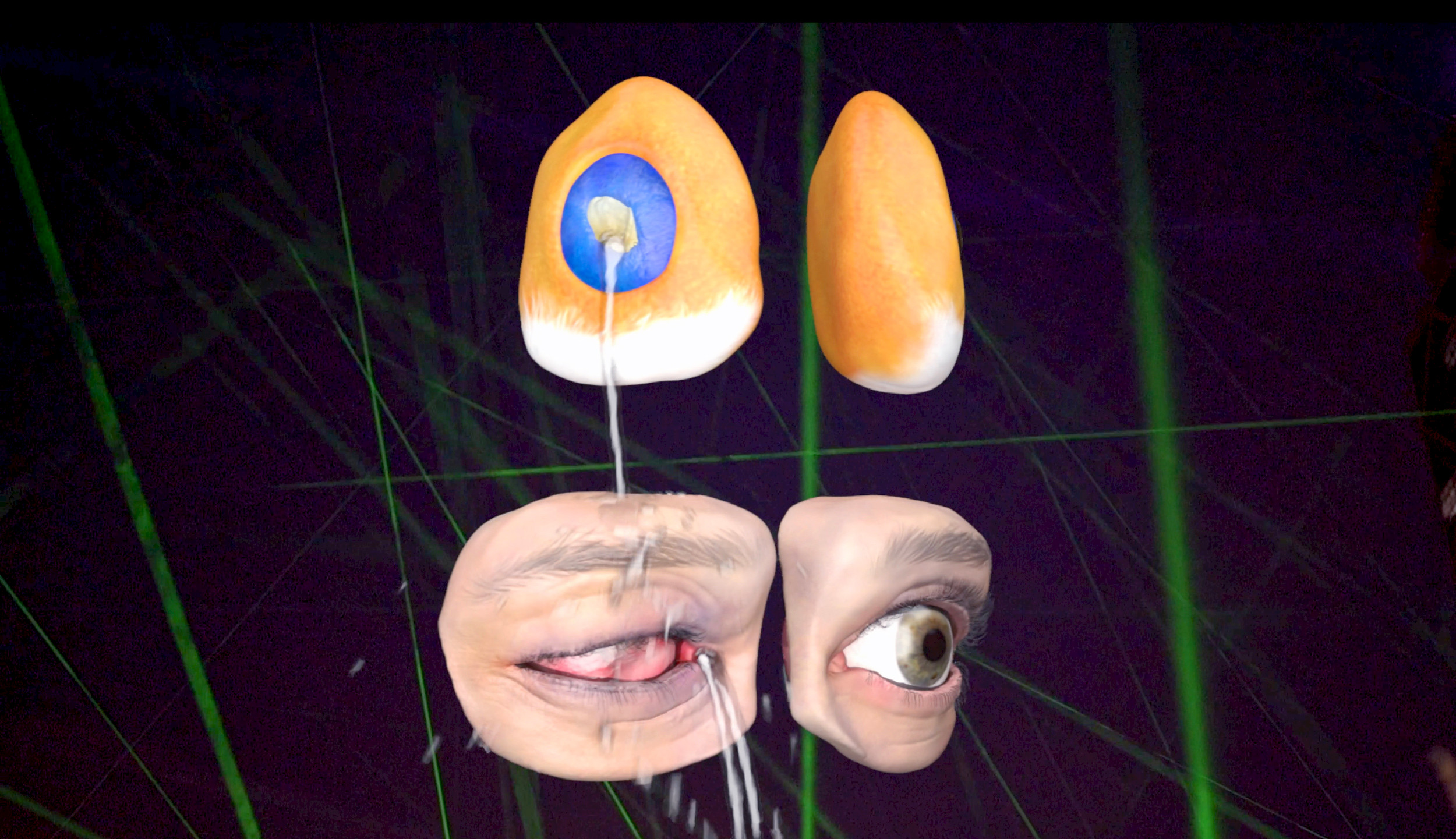

1. (Patricia refers to video installation Madre Drone; “In the video, the eyes of the toucan and the human eyes cry together in a South American cosmic cry. A myth in which drones weep, where blinded toucans can no longer see fire and where young humans protesting for dignity are forced to transcend the visible for the invisible, for a new vision, in every sense.” From Clot Magazine).

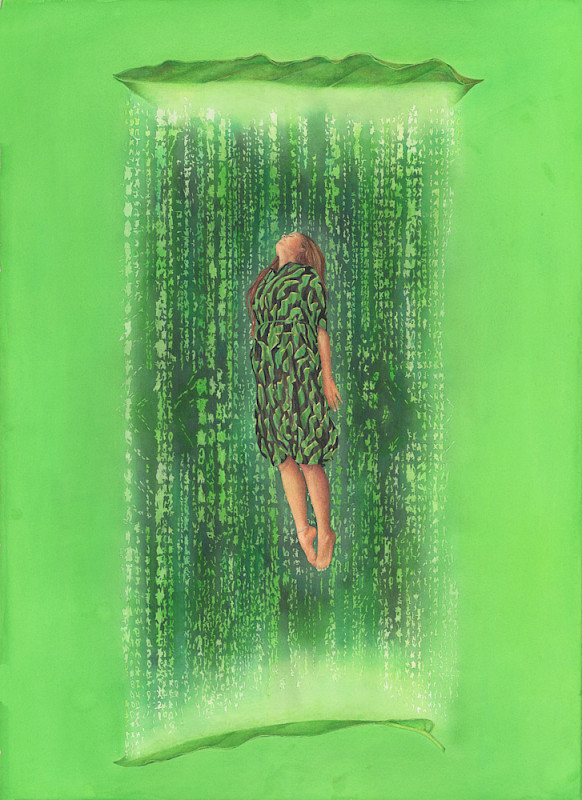

2. In the video work Matrix Vegetal, Domínguez creates a tribute to the power of sacred plants, with which she learned to connect to their more-than-human-language and knowledge, under guidance of Amador Aniceto in Madre de Dios, Peru.

3. A male traditional native healer or shaman form Latin America.

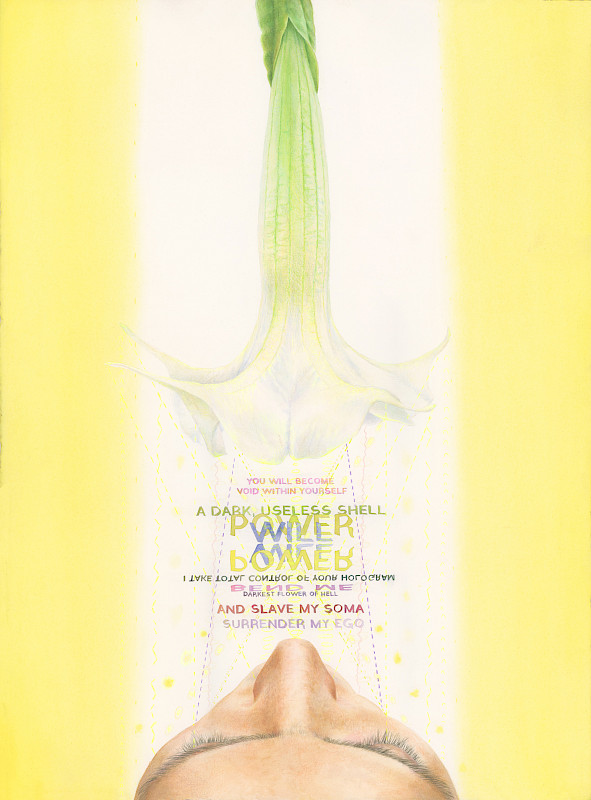

4. The 25-minute-long video entitled Eyes of Plants, explores the practice of healing with roses and other mestizo rituals emerging in the contact zones between radically different cosmologies.

6. For The isle of dogs; a curse in reverse (2017), Domínguez presents a sci-fi totem in which she merges Pre-Columbian iconography with corporate ideologies through an humoristic assembly of wellness objects associated with (coping with) late-stage capitalism and business shirts.

7. Millaray Huichalaf is a Machi, the spiritual guide and healer of her Mapuche Indigenous Community in southern Chile. Since 2011 she has led the defence of the Pilkamen river which is under threat from the construction of hydroelectric plants and has important cultural, medicinal and spiritual significance for the Mapuche.

8. La balada de las sirenas secas (The Ballad of the Dry Mermaids) (2020), for which she collaborated with Las Viudas del Agua **(The Widows of the Water), a group of women who are devoting their lives to the fight for access to water resources within their communities. The Ballad of the Dry Mermaids examines the complex flows of water in terms of the possibilities for crying, healing, and spirituality in the digital era. From https://www.museothyssen.org/en/node/21915