essay

A neon palindrome, lessons from the crouching man

Charlie Jermyn

Charlie Jermyn is a writer, essayist and performer from Dublin living in Amsterdam. His works include aural odysseys on landscape and art, the dissolution of bowling alleys, perambulation across nations, and travel writing from Balkbrug to Hong Kong, Dublin to Pavia. He is a monthly resident at Stranded FM Utrecht with his show More Poetry is Needed, where he has explored the poetic works of Arthur Russell, John Cooper Clarke and Van Morrison.

essay

The distant bungee jumper, a dangling herring

Charlie Jermyn was on a mission to discover the history of the North Sea resort town of Scheveningen. The essay tracks Charlie’s disorientating pilgrimage through a haze of mystical sea creatures, marshland, beached whales, kibbling, hungry gulls, and bungee jumpers.

essay

A devilish grin, a suburban carpark

Essayist and poet Charlie Jermyn makes a do-it-yourself pilgrimage through museum, muck, rain, wind and pub to visit Jan Steen’s old haunts

essay

Two Nights of Noise at Tivoli

By recounting his experiences of two formative concerts at Tivoli, essayist and performer Charlie Jermyn provides a poetic account on the raw power of sound and the music of everyday life. He connects the origin of noise music to Italian Futurism, a movement fascinated with dynamism and constant innovation, and appreciates the ongoing vitality of aging cultural icons amidst the decay of our time.

Mel Keane

Mel Keane is a designer and artist based between Ireland and the Netherlands, focusing on the media of drawing and music composition. His practice draws from a wide variety of sources, including folklore, metaphysics, and experimental music scores.

essay

The distant bungee jumper, a dangling herring

Charlie Jermyn was on a mission to discover the history of the North Sea resort town of Scheveningen. The essay tracks Charlie’s disorientating pilgrimage through a haze of mystical sea creatures, marshland, beached whales, kibbling, hungry gulls, and bungee jumpers.

22

min read

As subject matter, artists have forever been drawn to the apocalypse. Creation and destruction are at opposite poles of a spectrum, yet they reverberate off one another; one only exists if the other does, too. Something comes from nothing, nothing becomes something — and the role of art, as time goes on, is to dangle somewhere in the space between. As viewers, what lessons must we take from these works?

I previously wrote about the Lucas van Leyden triptych in the Lakenhal, Leiden. The white dove flaps above Christ in the clouds, and below: heaven, purgatory, hell. I described how the work miraculously survived the raging Protestant iconoclasm of 1566, the Beeldenstorm of white paint and fire. The Habsburgs under Charles V held power over the Low Countries from 1482. Charles’ son Philip II of Spain, the despotic heir, ruled the Low Countries during the Beeldenstorm. The emperor believed it was his divine right to violently suppress all heresy and protect the Catholic faith (1). From 1512 to 1566, the influence of the Spanish Inquisition spread to the Netherlands. Thousands of heretics were burned at the stake and punished for their beliefs. The result was the Eighty Years’ War, also known as the Dutch Revolt (1568-1648). It is important to understand the historical link between the Netherlands and Spain, as my journey begins in Spain.

Seville: Orange to Crimson

I was in Seville in July 2022. The air was stifling around La Giralda, the Moorish campanile beside the Cathedral. I found shade under trees in the wide-open squares where I saw oranges hanging from branches, growing heavy, dropping down, some had fallen in the gutter. Blinkered horses ferried tourists through the narrow streets, hooves squishing and kicking the citrus fruit. Juices burst onto the stone.

I had lunch: grilled salmon, stuffed olives and fresh anchovies in vinegar. I cycled, satiated, over the Guadalquivir River to the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo. The gallery is situated in the Monasterio de Santa María de las Cuevas, an old Carthusian monastery in Triana. The building’s function has shifted over the centuries from religious to military to clay manufacturing. The clay was pulled up from the nearby riverbank and moulded into ceramics. Now, the building retains signs of its past: the uniform lines of huge kilns. Through the entrance arch, there is a colossal sculpture trapped in a building. Inspired by Alice in Wonderland, the work by Cristina Lucas is called ‘Alicia.’

The lifeless eyes peered at me through a window into the quiet courtyard. A limp hand hung from another. The giant seemed imprisoned in the building, watching the world pass by. I entered the gallery, pulling back a black curtain. To my surprise, the monastery walls were entirely white. With a new devotion, contemporary art, it occurred to me that Spain has finally embraced the whitewash technique of the iconoclasts. I saw skeletal figures in a high-ceilinged chapel, made of fused together metal industrial elements.

The works by Giulia Cenci were part of the EXTRAÑO exhibition, meaning strange. I was fascinated by them. The sculptures connected to the walls by fine needles appearing like parched aliens that had drunk the frescos dry of their colours. The inscription describes contemporary art “as an unusual language that plays with the unknown and with that which is not familiar to us, the viewer tries to sense it but cannot fully grasp the meaning.”

I stopped at other works, finding myself lost in pendulous thoughts of curiosity and confusion. I saw the head of Heraclitus of Ephesus in a refectory, carved in cream-coloured marble. Vague and ponderous, the sculpture cast a shadow on the wall. In the 6th century BC, during his lifetime, the philosopher was known as ‘the obscure’ and his doctrine is often quoted: “No man steps in the same river twice because he is not the same man, and it is not the same river.”

Outside, shade was hard to come by as I walked amongst the kilns, through arid gardens and vast courtyards. I was relieved to find a bench in a cool chapel. In darkness with headphones on, I watched a short film by filmmaker and photographer Marine Hugonnier, ‘The Last Tour’ (2004). The film guides the viewer upward in a slow-rising hot air balloon.

I floated about the valleys surrounding the sheer peaks of the Matterhorn. Hugonnier says, “The space is shut down, like a crumpled map…” where below, the landscape shrinks as wolves and deer begin to roam the moss-covered concrete (2). The structures have now lost their initial function. The film poses the question of human-made spaces being returned to nature after being deemed inaccessible. Hugonnier juxtaposed images of Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds in Anaheim, California against the actual mountain. The theme park added forced perspective, miniature waterfalls and fake snow to make the mountain seem more ‘authentic’ (whatever that means). Hugonnier imagines a future of tourism where even nature is fenced off, the natural world envelops the created. We are left to fabricate imitations to preserve the landscapes in our memories, to drift off elsewhere, high up in a balloon.

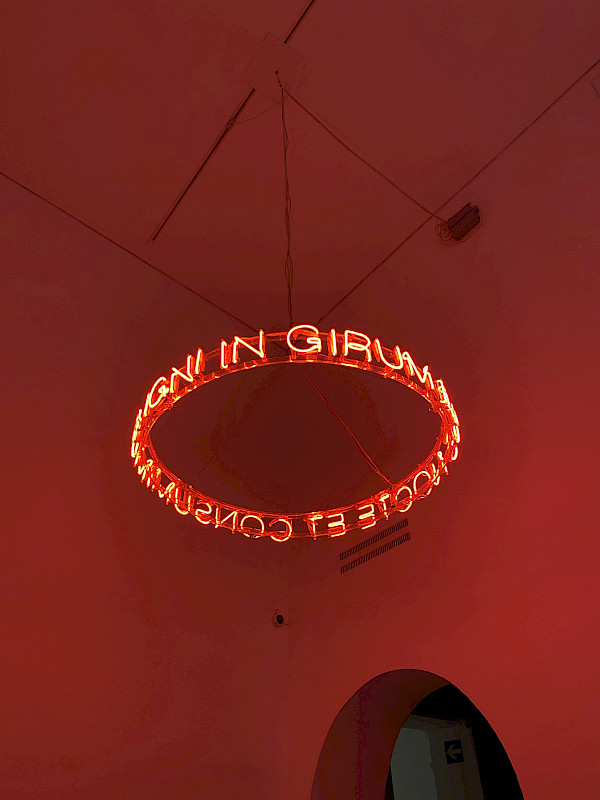

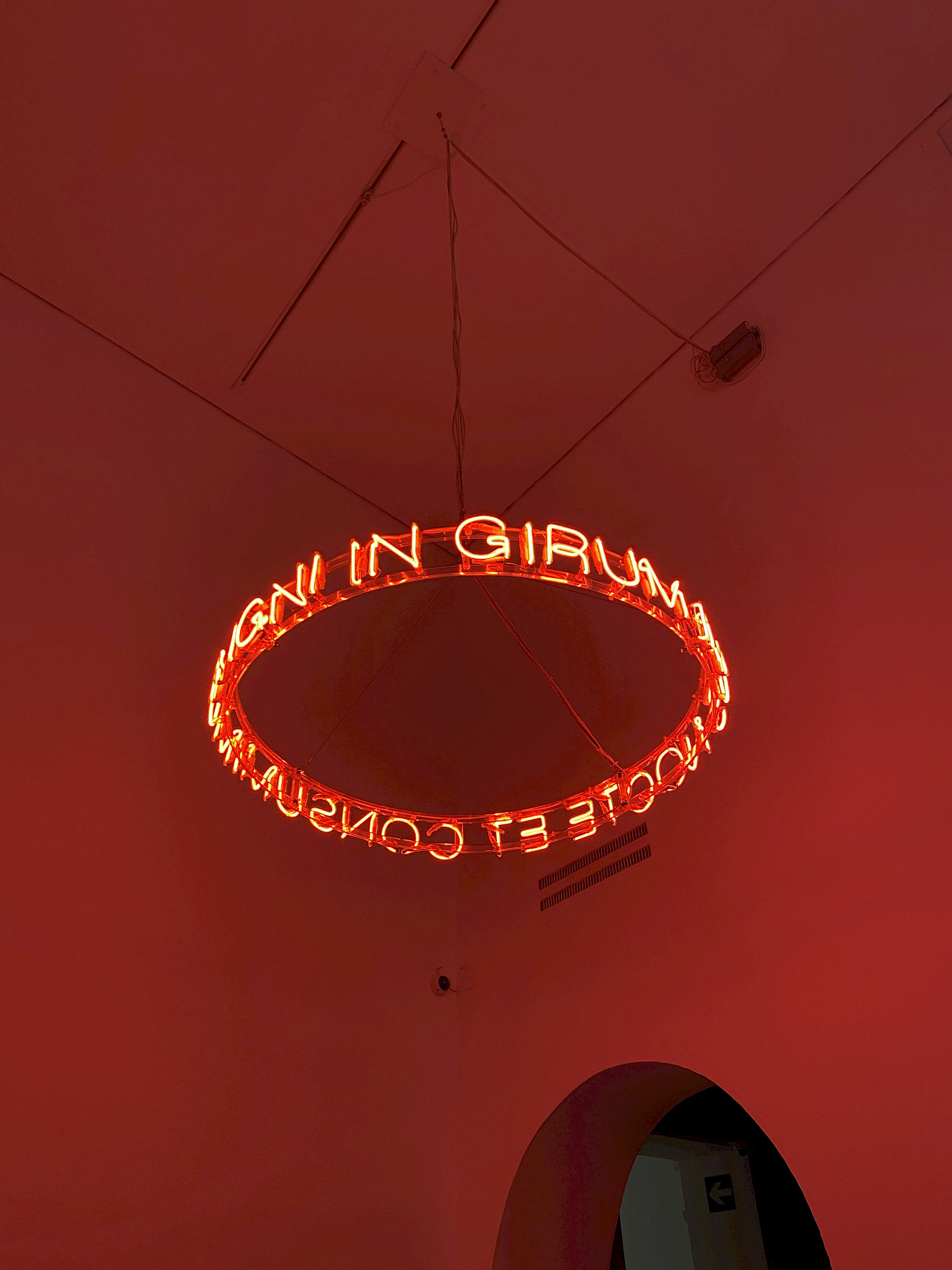

In a small chapel, a neon and plexiglass work hung from the ceiling like a crimson chandelier. My distorted shadow played like a puppet against the walls. The work by Cerith Wyn Evans (1958 -) is called ‘In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni’ (1999). The sentence is a palindrome in Latin meaning: "We go round and round at night and are consumed by fire." The circularity of the installation emphasises the meaning. It is an unending piece of work, a flat circle, whereby the mirroring effect of linguistic structures and physical movement dizzies all subjects. For the title, Wyn Evans was inspired by Guy Debord’s last film from 1978. Debord, the filmmaker and author, was a leading figure in the Situationist movement which raged against consumption and the commodification of society, believing in authentic, lived experiences (I wonder what Debord would think of Disney’s Matterhorn Bobsleds). In the film, Debord critiques the ‘Society of the Spectacle’ in his native Paris and beyond:

"Nothing expresses this restless present without exit better than this ancient phrase which comes completely back upon itself, which was constructed letter by letter like a labyrinth one can never leave, in a manner that so perfectly marries the form and content of perdition.” (3).

The pigeon of Osuna

The following day, I travelled by train south to Osuna. The town’s white walls reflected the mid-morning light. We were staying on a street leading up to the square called Calle Palomo—palomo is pigeon in Spanish. While waiting for the keys to arrive so we could open the door of the rental home, I noticed something by the curb. There was, on the street, the carcass of a pigeon. The dead bird lay peacefully in the slight shadow lining the cobblestones: broken wings, twisted feathers, a neck facing in an unnatural direction. Over my head, a pink flower curled from a rooftop. I thought the mark from peeling paint looked like a pigeon taking flight.

Later, I wandered to the Cathedral on the hill, La Colegiata. The tour guide showed us artworks on the life of Christ. In the background were lowland landscapes, flat horizons spread out behind the cross on the hill at Golgotha. The artists were from the Netherlands, and their style was popular in 16th century Spain. Down in the crypt, I saw the tombs of the dukes and duchesses.

While writing about my time in Seville and Osuna, I moved into a new flat in Amsterdam. Former tenants had left art books on the shelves. I flicked through an illustrated biography of Hieronymus Bosch, published in 1979, while melding together the memories from Andalusia.

Not much is known of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516), born Jheronimus van Aken in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the capital of North Brabant. We are left to piece together the surreal worlds of his canvases. The themes I confronted that hot day in Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo — perdition, floating, hellfire, endlessness, drifting through obscurity, the surrealism of existence, the spectacle — had a synergy with the macabre and hellish works of Bosch.

This Earthly Delight

Winter came. To learn more about Bosch, I went to 's-Hertogenbosch, or Den Bosch in January, Carnival was a week away. The bakery windows were full of Bossche bols, swollen cream-filled profiteroles, handsomely coated in rich dark chocolate fondant. It is an iconic, gluttonous dessert scoffed down in the days before Lent. During the three-day festivities, the people parade through the streets like court jesters, prancing, dancing, honking horns and blowing whistles. Caricatures of bishops, prime ministers and public figures are held aloft in mockery. In shop windows, I saw mannequins in hideous, gaudy outfits: striped nylon suits, clownish, curled hair, all embellished in sequins, fake moustaches, skimpy shorts, bucksome vests.

In the market square, I stood in front of the statue of Hieronymus Bosch. At the base of the plinth was a man sitting in tight patchwork trousers. Hunched over, he was revealing his arse-crack as he sat on the low step. On the cobblestones in front of me was an exploded mango. I recalled the oranges of Seville. A man, ketchup plastered on his cheeks, chewed lumps of kibbeling. A woman dug her hand deep into a paper bag, fishing for some chips. She dunked four at a time into a pot of mayonnaise. Fumes blew downwind from the cheese shop across the square. A leaking drainpipe formed a pool in the cracked cobblestones. Children splashed about in the water, annoying their parents.

Seagulls swooped near a herring stand while people pinched raw fish tails, drooping them over their open mouths. The birds scanned, heads twitching, for discarded bones and fish meat left unguarded on tabletops. The statue of Bosch oversaw all this from his plinth, brush in hand, a palette in the other, a skull cap on his head. A bird landed on him, squawked, and crapped. The liquid streamed down the bridge of the artist’s nose and onto his palette.

Birds feature widely in Bosch’s works. The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1503-1515), his most famous work (now in the Prado Madrid), is a spectacle from Genesis to the afterlife, a fantasy of what Bosch imagined awaited us after death (4). In the left panel, The Joining of Adam and Eve, the natural world blooms into life, Adam and Eve surveying God’s pure creation. Exotic birds of paradise and swallows swarm through mountain passes and stop to peck at fruit in the trees. In the second panel, we enter Purgatory, imagined as a gathering of oversized birds with people riding them like horses. The rivers flow through from the fountains of paradise. However, people have lost the plot, and lust is at the heart of the world. Nude figures cavort. An owl watches on: Cranes clack their beaks, unicorns, narwhals, pigs with big bollocks, petals for hats, strawberries the size of boulders, giant fish and mermaids with spiked tails. As well as observing visiting curiosities from afar, Bosch would have had access to ‘bestiaries’, showing pictures of animals and fabled creatures. A person peers sheepishly through a hole, resembling greatly ‘Alicia’ at the gallery entrance in Seville. Could it be Bosch himself imagining: “What is all this insanity?”

In the third panel, the hellscape shows a city ablaze, the brackish waters of canals and smoke clouds. In the year 1463, a great fire raged in the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, reducing thousands of homes to ashes. It must have left an impression on the then 13-year-old Hieronymus (5). Crowds move through the inferno. There is a giant off-white Tree Man staring out of the canvas, balanced on two small boats. In the Tree Man’s torso, a woman is pulling pints from a barrel. A man sits on a giant toad. There are bagpipes everywhere, a symbol of sloth and idleness. The drunkards are thirsty in the damnable tavern.

Further down, a person is being crushed by a giant lute, and tattooed on his arse cheeks are musical notes. A band member has a flute up his arse. The owl has now become a human-gorging demon, devouring and shitting on a throne-like potty.

I become dizzy looking at it, cast into a deep state of confusion. I ask myself: what does this all mean? John Berger in his essay on Bosch, summarizes the sensation of entering this eternal damnation:

“There is no horizon there. There is no continuity between actions, there are no pauses, no paths, no pattern, no past, and no future. There is only the clamour of the disparate, fragmentary present. Everywhere there are surprises and sensations, yet nowhere is there any outcome. Nothing flows through: everything interrupts. There is a kind of spatial delirium.” (6)

In contrast to Heraclitus, no river is flowing through Bosch’s hellscape. There are no reference points, you are shrunken, you are enlarged, you mutate within the canvas as you decipher the anarchy. From medieval iconography of hell, the violence of the Spanish Inquisition and the gluttonous and delirious celebrations of Carnival, Bosch pieced together his own depictions of hell, purgatory, and heaven. Bosch was teaching lessons in his work. The beholder would squirm in fear at the sightings of apocalyptic landscapes that called for piety and selflessness and warned of gluttony, the occult and other sins.

The Concert in the Egg

I have a postcard of The Concert in an Egg, a painting by a follower of Bosch. The artist was popular at the time, and his works were recreated. I like the painting for its absurdity. There are ten people in an egg. Amongst the claustrophobia, a monk tries to lead the group in song, pointing to the score. Faces are twisted in confusion. How did we get here? What is this alchemy? A heron stands on a trumpeter's head; another has an owl perched on his. A basket hanging from a twig holds a roast chicken and an apple dangling from a branch. One man has a building on his head; another is wearing a tin pot. A snake hangs from a tree (a reference to the tempter of Eve?); all around them is a barren wasteland and a looming inferno.

The world is crumbling and cracking. Nevertheless, the monk remains focused, like his existence depends on it. He does not notice his purse strings being clipped by a miniature man and a donkey-headed lute player. Never mind. The songbook is long, and there are many pages to turn.

The Concert in the Egg can be viewed as a hymn to the stupidity of human habits or salvation from foolishness. Incorporating popular expressions and proverbs into paintings was a favourite practice in Netherlandish art of the time. The strange imagery is most likely connected to popular Dutch expressions of the 16th century, the meanings of which have been lost. The original sketch by Bosch is all that survives.

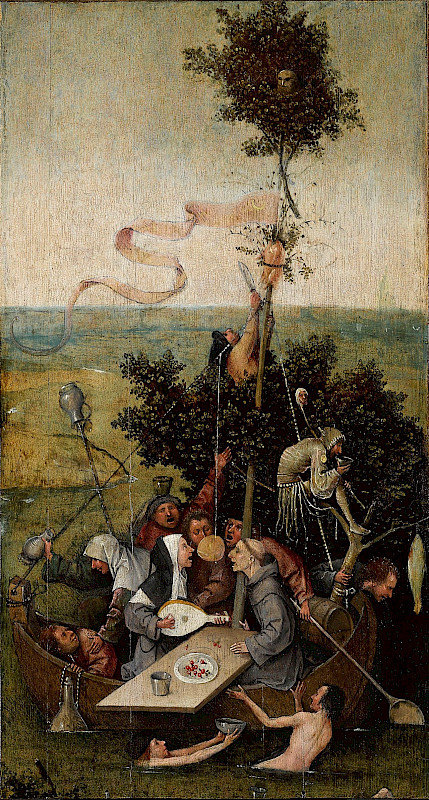

No harbours for the Ship of Fools

The Concert in the Egg mirrors The Ship of Fools, another work by Bosch. In it, a rag-tag group are tightly squeezed into a small vessel. They drift close to the shore without a landing place. Swimmers grasp for the boat, wading through the waters that seem as thick and dense as tar. Nearer the bright horizon, the sea brightens to a snotgreen. The ship’s mast is a tree, an owl watches over the scene from within the foliage.

Onboard, a monk sits opposite a nun plucking a lute. On the table in front of them is an overflowing plate of radishes. Their mouths are agape, trying to bite chunks from a cake lump swinging from a string. In the stern, a man is vomiting up his guts. A hunchbacked jester sups from a goblet. Two horns emerge from under his hood, his back is turned on the others. The lesson here – a popular satirical allegory for a criticism of the Church – is that folly does not belong to one social class but to all in the same boat, rudderless, floating in circles. On journeys with no end, where no harbour was in sight (7).

The works of Bosch transport me to a place near my childhood home in Dublin. I would often sit at Bullock Harbour on the south tip of Dublin Bay. Cliffs protect the natural inlet, and a harbour is built from the granite of the local quarry. Closing my eyes now, I remember the sea always held an oily glare, and rainbows appeared in the murk. Before me was a Boschian landscape of silt and brine. I would imagine myself shrunken, manoeuvring through the silt, hiding amongst grime-covered buoys, cowering from the monsters around me. I imagined conger eels, plump seals and silvery mackerel. Lobsters squirmed in rotting pots. Velvet crabs shuffled on the precipice of the departing tide. Over my head, birds scoured, pecking into crevices, scanning the slime, tearing at kelp, wondering what mysteries lay below.

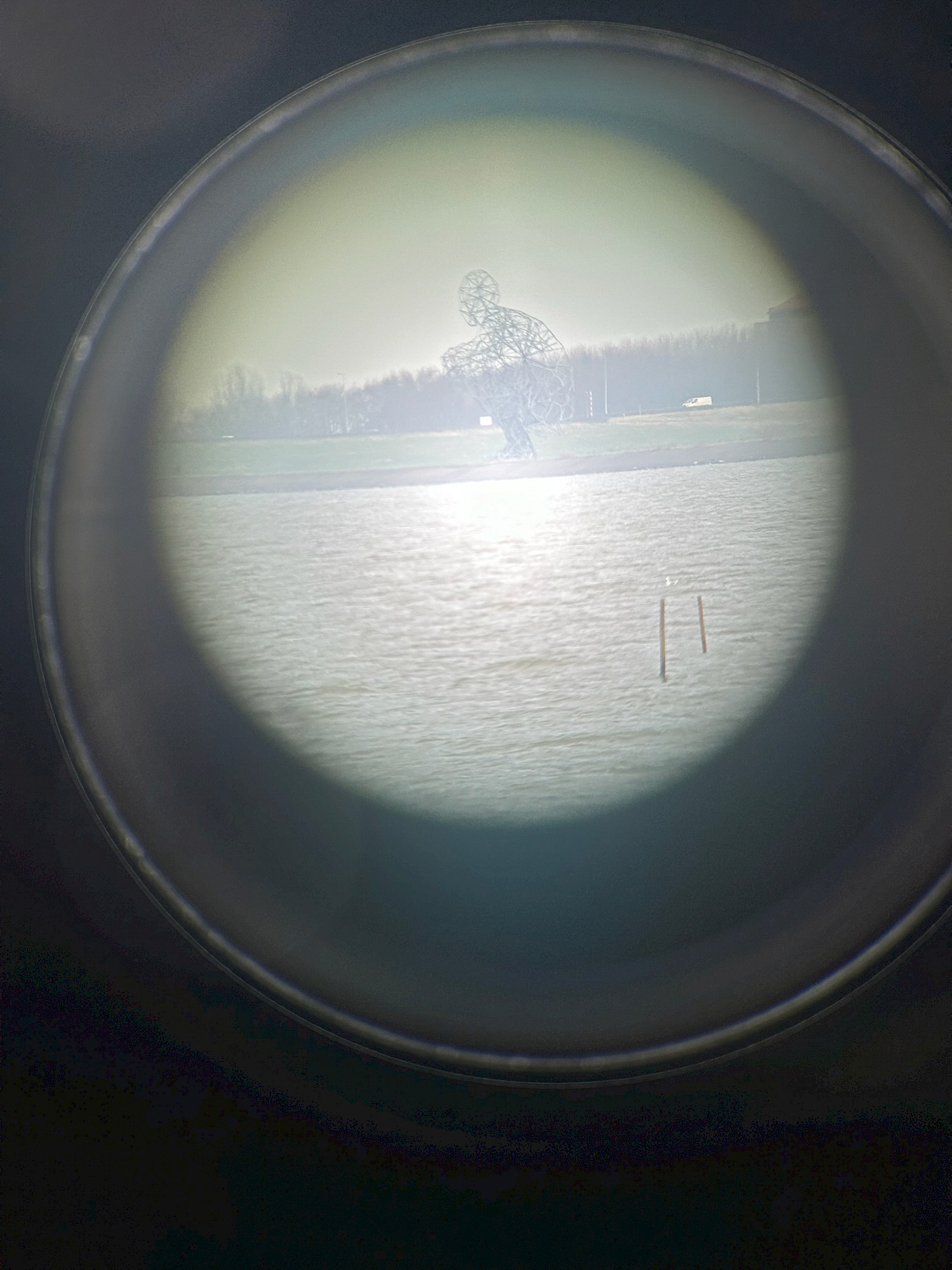

It was birdwatching that brought me to the next work of apocalyptic art. I had finished an afternoon birding excursion in Almere Oostvardenplassen in Flevoland; the region reclaimed from the seabed of the Zuiderzee in the 1960s. The day had clouded over, the rain was coming in. I asked the guide about the Antony Gormley sculpture near Lelystad. We pulled up on the dyke to and he pointed across the sound. Out of the car, I stared through the scope. I battled against the wind to find the figure, finally focussing on it, minuscule against the immensity of the world around it.

The work is called ‘Exposure’ (2010), and it is a 60 ton, 26-metre-high sculpture. The work is not by a Dutch artist, but it is ‘Dutch’ in its commentary on land reclamation, water management and rising sea levels. The work was christened de poepende man – the shitting man – by locals, but also, de hurkende man (crouching man). The Dutch humour of Bosch still can bring the lavatorial into high artforms. I took note that I would one day make it out to Lelystad.

To Lelystad & ‘Exposure’

I eventually made it to Lelystad a long time after seeing it through the scope. It was the week of April Fools. Spring has arrived. Tulips fields were exploding in colour. I rented a bicycle and pedalled through suburbia, under pylons that stretched to eternity. I stopped for directions at an outlet shopping centre called Batavia Land. Young families queued for ice cream happy with bags from discounted retailers.

‘Exposure’ came into view as I queued to cross over the bridges on the dyke. I was surrounded by Lycra-clad cyclists, articulated trucks, and Winnebagos, preparing to travel across the Zuiderzee to Enkhuizen. I was scared. On one side was high-speed traffic, and on the other was a drop down to the sea below. Crosswinds roared over the dyke.

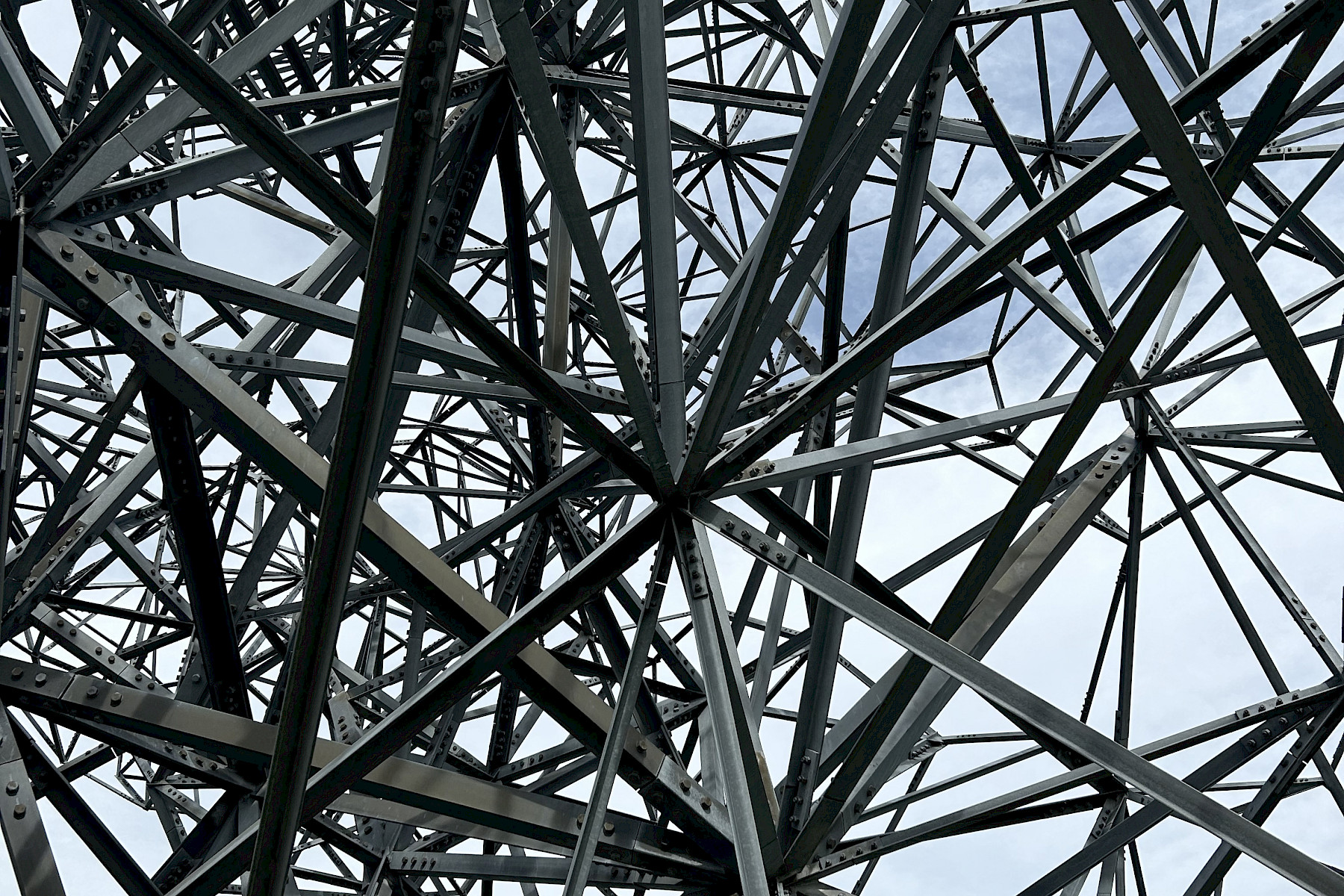

‘Exposure’ resembles the jumbled steel of electricity pylons that stretch into the flat lands, dotting uniformly as far as the eye can see. They are great monstrosities themselves, humming, buzzing, pulsing current across the lowlands.

Gormley wrote: “The whole idea of ‘Exposure’ is that this work, made at a particular time, rooted to ground, reacts over time to the changing environment.” (8) He aims to alter space so that it transforms, expands, or shrinks when someone or something is placed within it: A human, a giant, a minuscule sculpture. With the sculpture, no two steel members are equal in length. The materials were brought from Scotland to the Netherlands, the highlands to the low, and assembled on the dyke (9). From far off, it is a still point, rigidly there as the environment shifts around it. Gormley grimly foresees, as sea levels rise, the sculpture will slowly be submerged. Hunched over, the giant awaits its own disappearance as barnacles begin to cling on, shrouding the steel.

I curled down the path under the bridge, passing bikers with herring and chips. A beach bar was preparing for the summer months, painting its walls white again after discolouration from the wintry ocean spray. I parked by a crescent beach hugging the spit at whose end sat the giant metal figure.

The closer I got to the sculpture it metamorphosed into indecipherable beings, mutating constantly against the enormity of the seascape. I stood under the frame and impersonated his squat. In this regard, I felt I was part of a continuum. I think everyone who visits the sculpture strikes a similar pose and takes a photo in the act. Before me, the gust was powerful, the horizon without a blip. I read that if the sculpture could stand up, it would be 100 feet tall. Staring up into the metal, it was disorientating, hypnotic, shafts of sunlight made it through the rifts between the beams.

Christophe Van Gerrewey, in his article on ‘Exposure’ discusses the paradox of Dutch landscape evolution that to make space, to create distance, you must fill it with emptiness: “Exposure does not colour the space between heaven and earth black with people, but still makes the human presence quite inescapable in its own subtle and ‘transparent’ way.”(10)

Leaving Lelystad

As I walked away from the sculpture, its shape became clear again. On the beach, kitesurfers were preparing to take flight. Dogs pissed on boulders. Youths kicked around a football. And there was a boy, spectre-like in the bright spring sun. He was building sandcastles and splashing in the shallows. The sandcastles would blow down and get washed away with the tide. However, he would again, happily fill his bucket, flip it, slap it down and pull away to proudly reveal his edifices of sand.

My mind wandered to the flipping pages of the songbook for the concert in the egg, spinning around the neon carousel, rowing the boat gently into oblivion, and plucking the lute. Many of the lessons in all the artworks I wrote about in this essay hold different meanings now than they would have to the contemporary, religious viewer who was primed to understand. So, have we taken anything onboard?

Of course, there is some joy to be taken in the idea that the human condition finds some shimmer of wonder even in the direst of circumstances. Or are these just coping mechanisms to ignore the elephant in the room, or the giant on the dyke?

The boy stared out as the wind took the kitesurfers, flung out like fish on the end of a line. I unlocked my bike chain. Further away now, I could see through the sculpture—like a tree scant of its leaves. As Gormley says, “the landscape and surroundings always remain visible through the web of steel, from every angle.” Squinting, I spotted a nesting bird in the steel, I wish I had a scope, was it perhaps a pigeon? I felt it would be waiting a while for the gust to die down and hover placidly on a breeze.

I wondered: when the tide eventually rises and the white waves crash over the dyke, will this be nature’s version of iconoclasm? A return to nature, moss covering concrete, barnacles stuck to the steel, the waters reclaiming the seabed. The lessons to me are clear now from Gormley’s works. Inaction and indifference result in a loss of all understanding: A rudderless voyage towards an unknown, indistinct harbour. ‘Exposure’ is not a man taking a shit, trousers at his ankles, it is a prophecy of a climate disaster, an end of the world as we know it. The end of the world is a hyperobject – a term coined by Timothy Morton – meaning it has dimensions so large in space and time it is entirely incomprehensible to us. We must try to make sense of the warnings, stand up and step back for a clearer view, before it is all too late in the day.

Questions remain.

What of the owls and eggs shells, the radishes and unicorns? The tree man and the sandcastles? What of the oranges and the bobsleds? What of the tar-black seas and the monk singing into the void? What of the neon palindrome, the whitewashed walls, and that dead pigeon of Osuna?

Round and round the spectacle I go, thrown back to that bulky marble head of Heraclitus, the shadow on the wall. Pondering the waters, the rippling sensations, feeling the chill, sensing in that precise moment that the landscape is altering and ever-changing. And now, I finish with Aristotle’s interpretation of the doctrine of Heraclitus:

“All things are in motion, nothing steadfastly is.”

References

1. http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/caac/programa/extrano22/frame.htm

2. Interview in ‘Sabzian’ with Marine Hugonnier, https://www.sabzian.be/director/marine-hugonnie

3. Guy Debord, La Société du Spectacle, (1967) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mjF6I6SYjgA

4. Digitalization of the Millenium Triptych: https://archief.ntr.nl/tuinderlusten/en.html

5. S. Orienti, R. de Solier, ‘Hieronymus Bosch’, Crescent Books, 1979, pp. 26-29

6. John Berger, Portraits, Verso, (2015), p.36

7. S. Orienti, R. de Solier, ‘Hieronymus Bosch’, Crescent Books, 1979, p. 63

8. Antony Gormley, ‘Ground’, Museum Voorlinden

9. Details on construction of ‘Exposure’: https://www.antonygormley.com/works/making/exposure

10. Christophe Van Gerrewey, Attracting Lightning Like A Lightning Rod, https://www.antonygormley.com/resources/texts/attracting-lightning-like-a-lightning-rod