essay

A devilish grin, a suburban carpark

Charlie Jermyn

Charlie Jermyn is a writer, essayist and performer from Dublin living in Amsterdam. His works include aural odysseys on landscape and art, the dissolution of bowling alleys, perambulation across nations, and travel writing from Balkbrug to Hong Kong, Dublin to Pavia. He is a monthly resident at Stranded FM Utrecht with his show More Poetry is Needed, where he has explored the poetic works of Arthur Russell, John Cooper Clarke and Van Morrison.

essay

A neon palindrome, lessons from the crouching man

“In the name of contemporary art, Spain has finally embraced the whitewash technique of the iconoclasts.“

essay

The distant bungee jumper, a dangling herring

Charlie Jermyn was on a mission to discover the history of the North Sea resort town of Scheveningen. The essay tracks Charlie’s disorientating pilgrimage through a haze of mystical sea creatures, marshland, beached whales, kibbling, hungry gulls, and bungee jumpers.

essay

Two Nights of Noise at Tivoli

By recounting his experiences of two formative concerts at Tivoli, essayist and performer Charlie Jermyn provides a poetic account on the raw power of sound and the music of everyday life. He connects the origin of noise music to Italian Futurism, a movement fascinated with dynamism and constant innovation, and appreciates the ongoing vitality of aging cultural icons amidst the decay of our time.

Kalle Mattsson

Kalle Mattsson is a Stockholm based graphic designer, illustrator, animator and some sort of graphic comedian, which he would like to take this opportunity to apologize for.

column

You Gotta Serve Somebody

“Hello” I typed, and it felt like flinging sound into a cave, testing to see if someone was there in the dark, some being of an undetermined image.

essay

Two Nights of Noise at Tivoli

By recounting his experiences of two formative concerts at Tivoli, essayist and performer Charlie Jermyn provides a poetic account on the raw power of sound and the music of everyday life. He connects the origin of noise music to Italian Futurism, a movement fascinated with dynamism and constant innovation, and appreciates the ongoing vitality of aging cultural icons amidst the decay of our time.

column

You Wanna Know How We Got These Scars?

Writer, cultural critic, and philosopher Ben Shai van der Wal calls upon us to embrace our trickster-friend. A short essay about how society’s need for healing and fixing stands in the way of it.

19

min read

There is a painting by Jan Steen in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. The work is called The Village School (c. 1665). The scene depicts a boy being punished by his teacher; fellow pupils surround him. In the centre of the large canvas there is a girl with a devilish grin. Teeth protrude from her curved mouth. She stares ferociously at the wooden spoon in the teacher’s hand: a moment of anticipation just before the smack. The girl is the embodiment of leedvermaak, where one experiences joy in another’s suffering. From the first time I saw the painting, the malicious pleasure plastered on her face was imprinted onto my memory. Whenever I return to the gallery, her stare meets mine and I always cannot believe she has managed to pull this face. It seems an impossible facial expression, but then again, this is a painting.

Steen’s works often feature life lessons, always preaching moral sensibility to the young and encouraging elders to take responsibility for their actions. The artist painted this as a warning to all: Do not take joy in another’s unfortunate circumstance, you could be next.

Jan Steen was born in Leiden in 1626. He painted landscapes and portraits, but he is known primarily for his genre paintings of raucous households and taverns. To the point that there is a saying in Dutch, een huishouden van Jan Steen:a space that is cluttered, chaotic. I once used this phrase to describe a Dutch friend’s house to their face. I thought it meant ‘this place is charmingly old’ or ‘authentically Dutch’. The house in question was built in the mid-seventeenth century, with creaking floorboards, steep staircases, a narrow attic space and wide windows that looked down onto a cobbled courtyard. Her face became as skewed as Jan Steen’s schoolgirl. She told me the true meaning and my face reddened.

When I first moved to Leiden, I walked a lot. I watched pigs eating muck in Polderpark Cronesteyn, I stared at my reflection in deep brown ponds, observed the cows of Warmond, and felt the flutters of butterflies in the Hortus Botanicus. I sat by the lake of Het Joppe with curious geese, swam in the North Sea near Katwijk and heard frogs out in the meadows of Sassenheim. At the time, I was reading the book An Island in Time by Geert Mak about the changing state of the Dutch countryside, the shifting landscape and identity crisis of his hometown, Jorwert. He writes:

Regulating, organising, the Dutch have always been masters at creating their own nature. It was no coincidence that, as early as the end of the sixteenth century, it was the Dutch word landschap that permeated the English language as “landscape”. In this country, kept dry and habitable by human hand, the idea of landscape was bound to crop up early on: a piece of nature whose qualities could be admired or rejected, and that was constantly being created and recreated.[1]

The Dutch were masters at manufacturing landscapes, a mimicry of nature. They reclaimed the land, planted trees, flooded peatlands and forged polders. In The Embarrassment of Riches, Simon Schama discusses the two worlds that Dutch artists, contemporaries of Jan Steen, brought to life:

Dutch art invites the cultural historian to probe below the surface of appearances. By illuminating an interior world as much as illustrating an exterior one, it moves back and forth between morals and matter, between the durable and the ephemeral, the concrete and the imaginary, in a way that was particularly Netherlandish.[2]

The words of Geert Mak, the interiors of Steen’s genre paintings and the walking outdoors made me want to see these landscapes through the artists’ eyes. In entering these worlds, I felt I could better understand my new adopted home. I went to Lakenhal, the municipal museum of Leiden, one summer evening on a route I mapped to take in the life and times of Jan Steen in five steps:

Landscapes in the Lakenhal

The piss artist

The stink of the Langebrug

Iconoclasm in the Pieterskerk

A carpark in Warmond

Landscapes in the Lakenhal

Lakenhal, on the Oude Vest canal in Leiden, was the centre of the cloth industry (laken: cloth). Built in 1639, it housed the guild of cloth merchants responsible for quality standards. Textile manufacturing had made Leiden one of the most prosperous cities in the Netherlands.

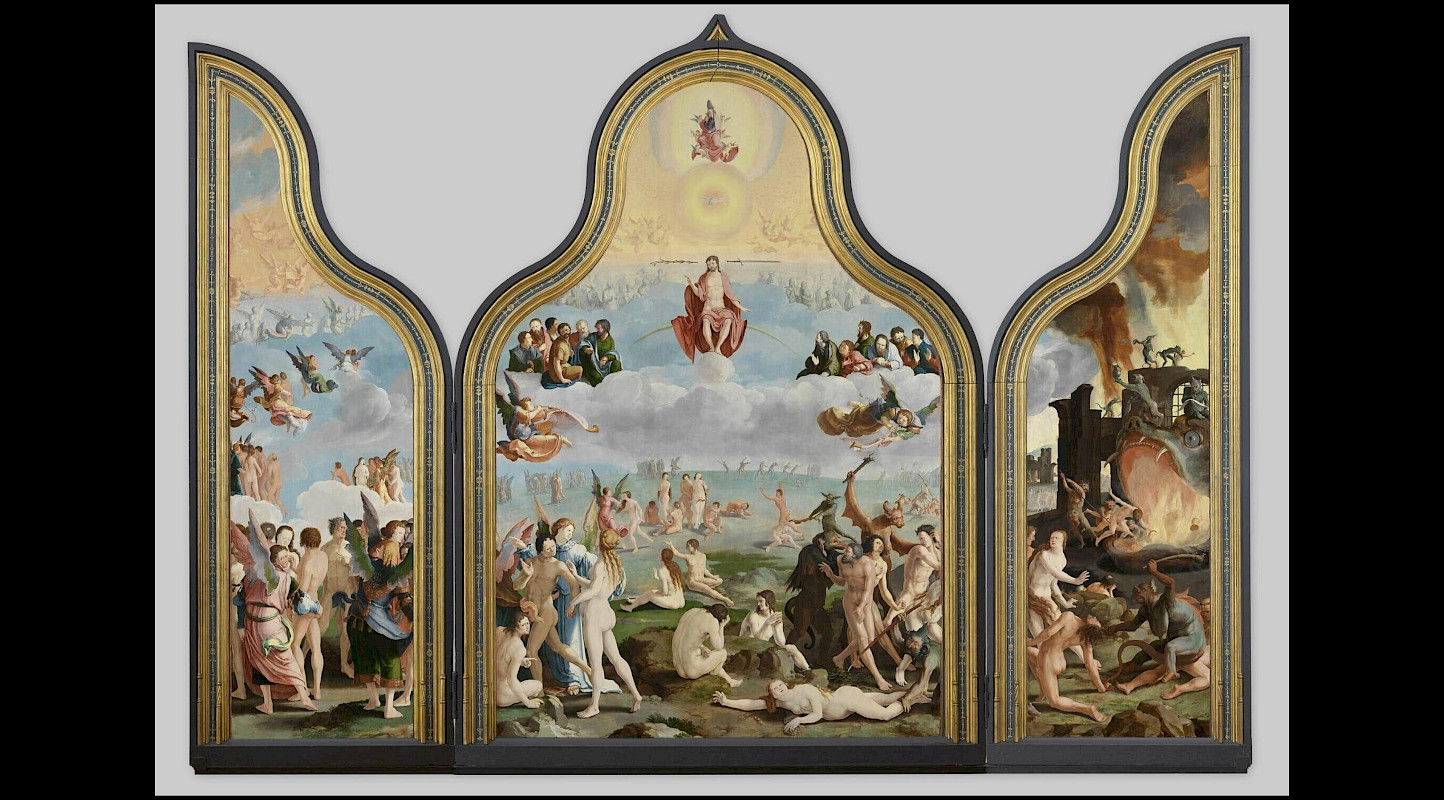

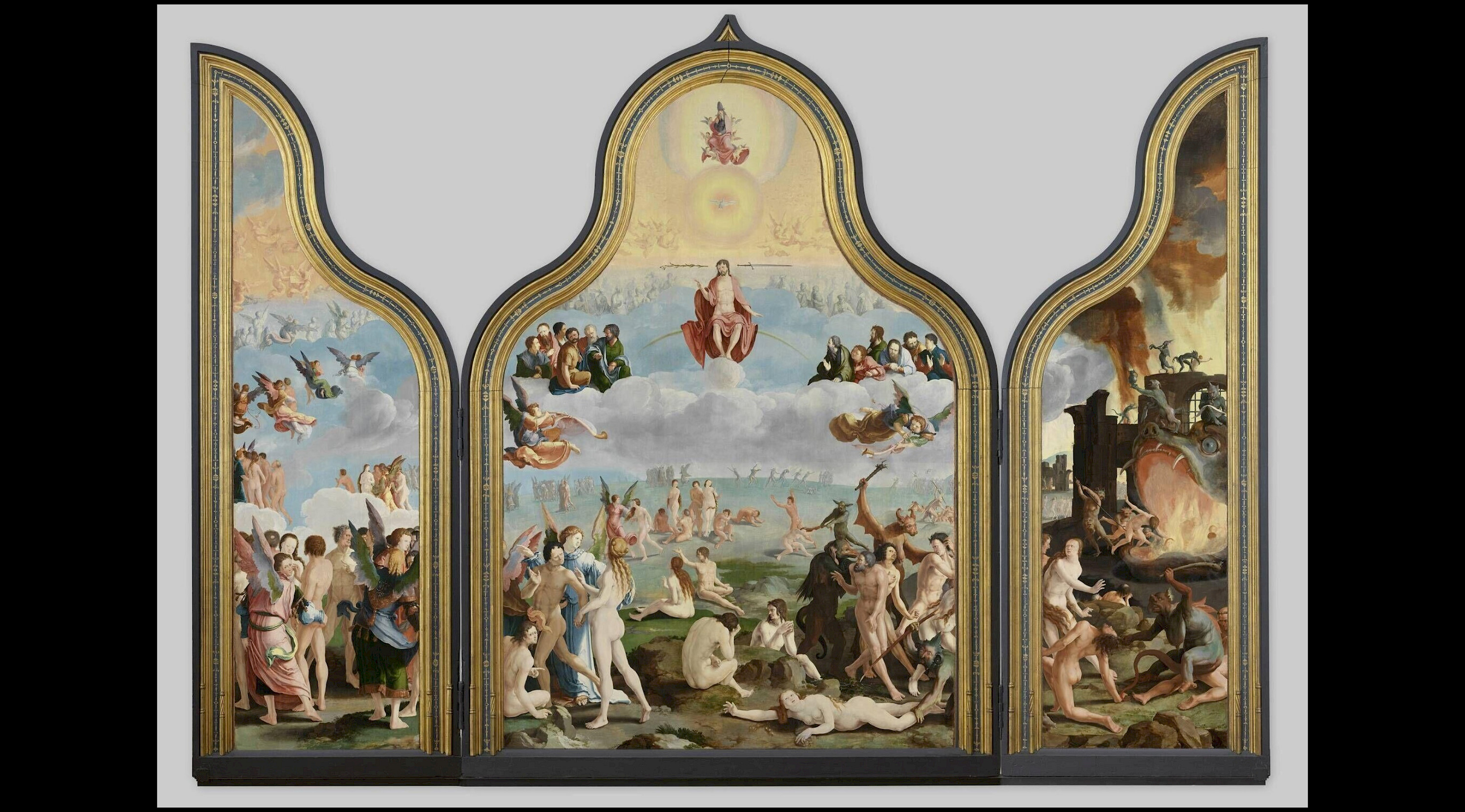

Several works of Dutch Renaissance art fill the first room. These are biblical paintings that were saved from the iconoclastic fury, or beeldenstorm, of Protestants in 1566. White paint and hot flames were the early embers of a cultural revolution. The vast altar piece dominating the space is Lucas van Leyden’s Drieluik met het Laatse Oordeel.

On the right shutter of the triptych, a foul beast emerges from a trench, belching flames. An unfortunate nude individual is catapulted into its gullet - de Hellemond. The central panel shows Christ floating on a cloud, crimson robes draped over his shoulders. The sun beams down upon his head; angels float in the air. A solitary white dove hovers over it all. There are saints on the left panel, luminous beings packed in a queue awaiting ascension. There is a brazen, winged angel, turned towards the observer, the full flat of its hand resting on the arse cheek of a very muscular man.

In the seventeenth century, a new mode of worship arose in the United Provinces of the Netherlands. The Bible and nature were commonly believed to be the twin sources of divine understanding. The pious Calvinist Constantin Huygens wrote that ‘God’s goodness appears on every sand-dune’s top.’[3] The art that arose at this time was not spiritual in the sense of the biblical and Italianate landscapes of the earlier century. It was plebeian and accessible - not reserved for the rich but for everyone. Piety was reflected in the modesty and humility –the most important values of Calvinism – of the landscapes. The Netherlandish landscape became source material for artists, where paintings became a commercial enterprise at marketplaces, rarely commissioned by individual patrons.

In the next room in the Lakenhal, there are landscapes by Jan van Goyen (Leiden, 1596 – The Hague, 1656). In these seascapes and landscapes, van Goyen used the wet-on-wet technique, revolutionary at the time compared to the traditional layered approach of oil painting.

Dune landscape with figures (1632) shows a place of constant rain, there are no mountains, no hills, to sop up the moisture. The clouds fly in over the dunes from the North Sea. The rain can be fleeting but heavy. In van Goyen’s landscapes, the sky dominates the canvas. In the shallow foreground, the dunes are starkly brown and silhouetted against a sky of luminous grey. The sun has broken through, illuminating the grass in gold. Two men in wide-brimmed hats inspect the area on horseback, while others poke at the dunes with sticks. In Sailing and rowing boats in an estuary(1640), van Goyen takes us out beyond the dunes into to the North Sea, capturing the ever-changing currents in the violence where river meets sea. The boats get battered. Distant gulls are blown in all directions. A break in the clouds, a moment of bright relief in a dark world. A fisherman hauls up the net, hoping for the wriggling of fish.

The Netherlandish landscape became source material for artists, where paintings became a commercial enterprise at marketplaces, rarely commissioned by individual patrons.

View of Leiden from the northeast (1650) shows Leiden as it would appear to a traveller floating on a barge over the River Zijl towards town. There are plains of wet mud either side of the water, where cows chew their cud under the clouds. Shipwrecks, sunken earth, horses, cattle carts, rotten planks and fishing boats fill the hinterlands. Ducks float around a barrel. Two churches dominate the townscape, and here’s where it becomes obvious that artistic license - keurlijk natuurlijkheid, a selective likeness to nature - was attractive to van Goyen. The Hooglandse Kerk is seen from the east so that the half-finished nave remains hidden, while the Pieterskerk is shown from the north to show off the high nave. Artists felt free to modify, adjust and rearrange what lay before their eyes, for the simple fact that it just looks good.

Jan van Goyen was in high demand and earned good money off his paintings. He speculated on both property and the budding trade of tulips. The flowers were brought to Leiden, by way of the Byzantium and Spain by the aged, well-travelled botanist Carolus Clusius in 1593. He had spent time in Vienna tending to the imperial gardens. He preached for aesthetic appreciation of tulips, encouraging the nobility to stop seeing them as edible, colourful alternatives to onions. Clusius took up a position at the university, arriving at the Hortus Botanicus with an extensive collection of tulip bulbs.[4]

In January 1637, van Goyen bought bulbs off Albert von Ravensteyn, a burgomaster from The Hague - midnight blue, black sky, sun yellow, a blaze of crimson… Stand amongst the landscapes in Lakenhal, and you can see why such colours drove crowds of collectors into Tulipomania – the great economic bubble which burst in February 1637. After the crash, von Ravensteyn and his heirs pursued van Goyen for repayment. The elderly van Goyen returned to the easel. He painted desperately and prolifically and arranged public auctions of his work, then died, insolvent, two decades after the crash. At the time of his death, his debt was 897 guilders – about 50,000 euros today. In total, van Goyen painted 1,200 landscapes.[5]

In 1648, Jan Steen registered as master painter in the Guild of Saint Luke in Leiden. Jan van Goyen was his teacher and they got along well. Steen seduced Goyen’s daughter Margriet and with van Goyen’s blessing and a baby on the way, they wed on 3 October 1649.[6]

The piss artist

In the next room, there are two paintings by Steen: ‘De koekvrivjer’ and ‘De piskijker’ (both c. 1663-1665). Both paintings depict interiors of homes with an underlying erotic message. De koekvrijver – the gingerbread suitor – is a reference to a strange 17th century act of courtship whereby a man would give the woman of his dreams a gingerbread man. He holds the long cookie suggestively. The elegant woman shows no interest in her wooer, with his ill-fitting clothes and bad manners (he left the door open). She carries on with her needlework and glimpses directly out of the canvas with eyes that say, who is this foolish man? and close the door on your way out! I wonder, did Jan present Margriet with a ginger biscuit? He was more successful with his seduction.

In De Piskijker – the piss examiner – a physician holds up a bottle of urine. He is inspecting it, swirling it around. An old woman leans on a table and looks on in interest. A young woman is seated, waiting for his decision. On closer inspection, you can see the doctor has put his shoes on the wrong feet. We are left with the impression that this is a deeply buffoonish man. In Steen’s eyes, he cannot be trusted.

In the next room, there is another, larger work by Steen, De Bestolen Vioolspeler (The Robbed Violin Player). In this work, as in many others, Jan Steen has portrayed himself as a character in the scene. As John Walsh writes in his analysis of Steen in ‘The Drawing Room’:

[Steen] is frequently an actor is his own scenes and changes costumes constantly: he is a drinker and hell-raiser in scenes of carousing; he is a fool; he is the prodigal youth whose whoring and time-wasting are good for entertainment and supply a message. Sometimes he is the witness that points out the moral to the spectators.[7]

Here, Steen is the red-faced drunken violin player, a piss artist, the egger-on of follies and joyous excess with a stomach full of ale, merrily plucking away on his violin. However, he is distracted. While ogling a lady, behind him a thief reaches for his money purse.

And there in the thief’s face, the grin, a devilish grin, I am reminded of the schoolgirl’s curved toothy smile in The Village School in Dublin. The thief’s face, dark under the hood, with a toothless and wide grin as deep as the jaws of hell in Lucas van Leyden’s Last Judgement.

I leaned in too close, and the proximity alarm went off. A security guard entered and asked me to keep my distance. I nodded and left the room. He also reminded me that the gallery closed in ten minutes. On my way up the stairs, I read a poem by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer pasted on the walls:

De tijd sloopt slordig, morst herinneringen,

laat kliekjes over en lekt residu

van hoe het was voordat het werd als nu.

Geheugen woont in de gewoonste dingen.

Time’s demise is sloppy, spilling memories,

leaving leftovers and leaking residue

of how it was before it became as it is now.

Memory lives in the most common things.

In his work, Jan Steen painted the passage of time, warnings of youth fading away, of the ills of individuals impacting the next generation, of burning the candle at both ends and tankards of ale frothing over in revelry. The lines of the poem reflect the painter’s oeuvre: objects scattered, detritus of mirth, wax drips off a candle, overflowing goblets, memories spilt on the floorboards.

From simple settings to scenes of mayhem, Steen could teach a lesson that should last us a lifetime. Steen’s first biographer Arnold Houbraken described Steen as an anarchic drunkard but much of the research was based upon his paintings and the descriptions of a disorderly Steenian household:

The room is topsy-turvy mess, the dog eating from the pot, the cat making off with the bacon, the children rumbling around on the floor, the mother sitting comfortably in a chair watching all this, and as a farce, he himself there too, with a roemer in his hand, while a monkey on the mantel stared with a long face.[8]

Yes, Jan Steen taught moral lessons; however, he wasn’t the wielder of the punitive wooden spoon. There was humour to his work. He was illuminating the interiors of Dutch society, it was educational, approachable art opening the doors to all. [9]

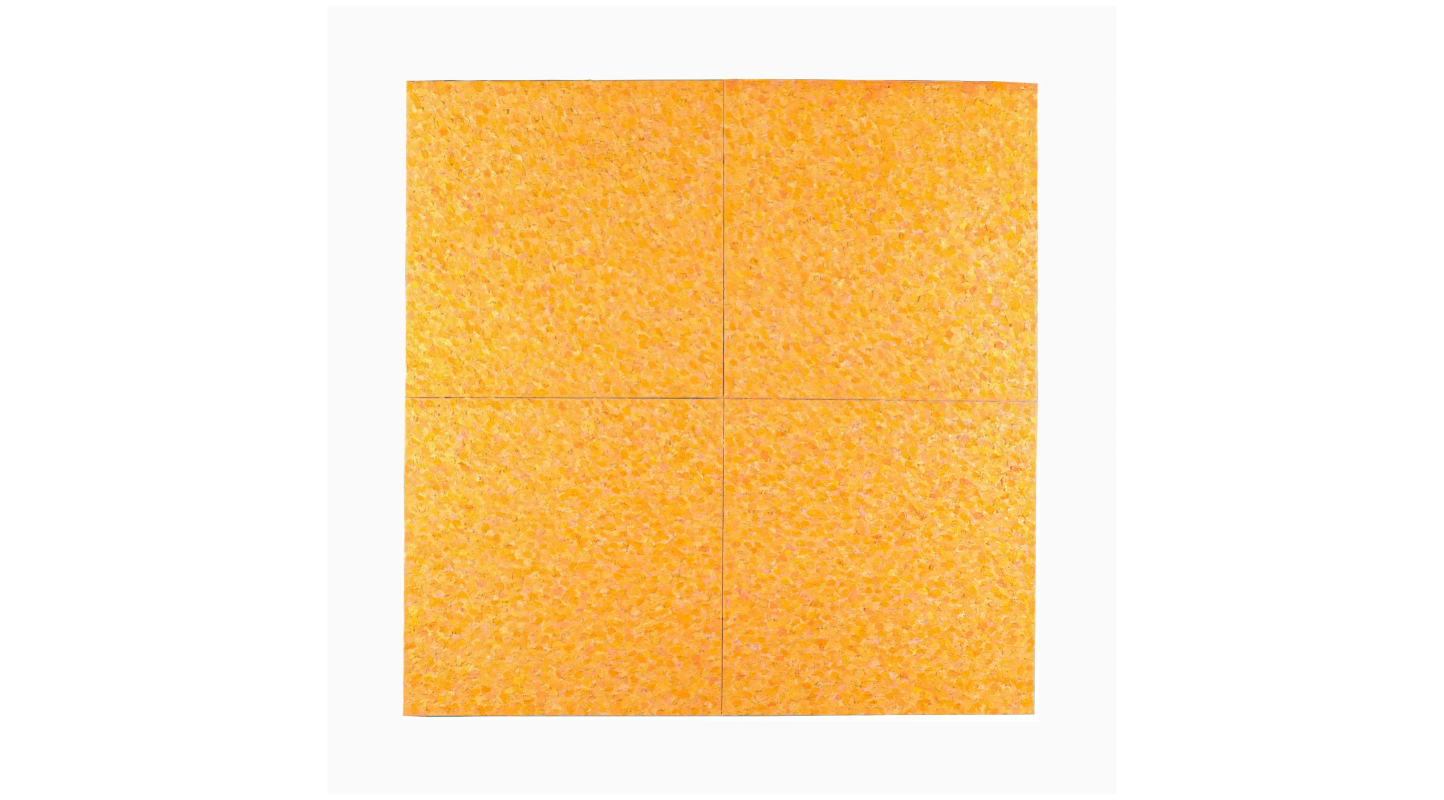

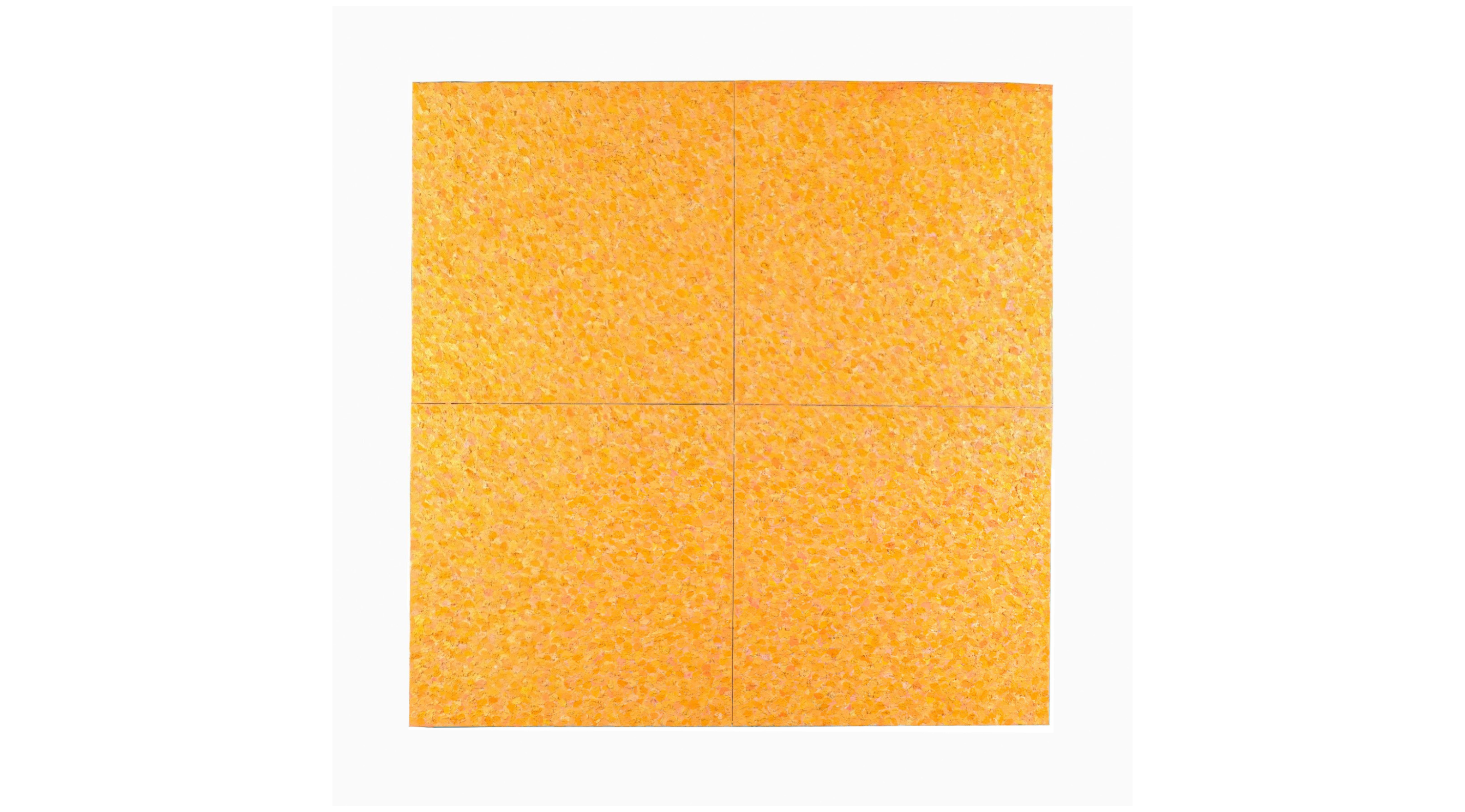

At the top of the stairs, with time for one more painting, I stopped at Jan Wolkers’ last major work – the abstract Het Grote Gele Doek (The Big Yellow Canvas, 2006). A third Jan, born centuries after the others. He's applied the paint in small strokes in subtle shadows and radiant colour. The colour was inspired by the yellow autumn leaves falling off the tulip tree beside his studio on the island of Texel. Wolkers grew the tree from a cutting from the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden. The canvas was like a bright yellow tulip, mesmerising, entirely absorbing, the same way the new primary colours introduced to the Lowlands drove speculators to ruin. I left the museum, walked over the Oude Rijn and into the commercial centre. I saw seagulls eating burgers, stolen from diners on barges. I made my way through the narrow streets until I reached Langebrug.

The stench of the Langebrug

In the Middle Ages, Langebrug – now a narrow street – was an important canal called Voldersgracht. The name indicates that this was the fullers’ quarter. I read that during the night naked fullers stamped for hours with their bare feet on woollen cloth in large tubs which contained a stinking mash. The stench was horrific – it was the urine in the concoction that served to align out the fibres in woven fabrics. Throughout the 17th century, Voldersgracht was slowly covered by stone vaults and by the end of the century no water could be seen. The canal was turned into one long bridge.

In this stinking dominion, Jan van Goyen and Jan Steen lived and worked. At the corner of Schoolsteeg stands the house where Jan van Goyen was born. I once had a beer there; it is a bar now. There was a jukebox, the stained green carpet of a pool table, bent cues, chalk dust, the beeping of a slot machine. The floors were sticky. I remember thinking Jan Steen would’ve loved this place. Steen lived for a while between no. 90 and 89 and opened a tavern here. There was a gate at the end of the street that led to the Penshal where, to add to overall stink, offal and tripe were sold under municipal supervision.

Iconoclasm in the Pieterskerk

The Pieterskerk rose up high above the Langebrug. I entered the quiet and secluded courtyard of houses, through the Gekroonde Liefdepport, away from the street, away from the stink and into the church. In 1512, shortly before Jan van Goyen painted the Pieterskerk, the 110-metre-tall bell tower - Coningh der Zee, King of the Sea – collapsed. It was here that Het Laatste Oordeel by Lucas van Leyden was saved from ruin.

The woman at the welcome desk warned me that I had thirty minutes before the church closed for a private function. In the central nave, there were tables adorned with white tablecloths, floating balloons and violet-coloured tulips. A man fiddled at the audio mixer. The speakers crackled, echoing toward the high stone ceiling space. Jan Steen was buried here in a family plot in 1679 and there was, somewhere, a plaque honouring him. I tried to find it, but I struggled. The crackling stopped and music began to play, a vomit-inducing acoustic rendition of Cyndi Lauper’s True Colours, complete tripe. No, this was the devil’s bagpipes. The anthem looped again and again as I kept scanning the walls. In this sacred place, this was a crude new form of iconoclasm. I was in a hellish, dizzying circle, wandering around a labyrinth of pillars, altars, apses and transepts.

The music cut out and I was freed from its burden like a winged angel. Squinting my eyes, I made out the indistinct name of Carolus Clusius, the botanist and bringer of tulips, and then, turning, I spotted it, the name in gold, etched into the grey slab of a pillar: Jan Steen.

A carpark in Warmond

I left the church. Rain clouds drifted over my head as I cycled towards Warmond where Steen lived and owned a tavern for a short period in 1660. He painted Poultry Yard here. An elderly couple lives in the former tavern; I saw them through the window peacefully reading in armchairs. As a result of Calvinist society, it was believed that a pious person had nothing to hide from God or neighbour, so they didn’t put curtains over their windows (this continues in the Netherlands to this day). The old man’s spectacles sat low on the bridge of his nose. I approached the building and the lady stared at me; I was trying to read the inscription on the wall. I smiled, she returned to her paper.

I crossed the street and stopped. I stood staring at Jan Steen’s carved bronze cheeks. There was no alarm telling me to back away. Up close, our nose tips were almost touching. His hair fell onto his shoulders, on his fleshy face his brow furrowed with bemusement. I saw no devilish grin. He had little holes for pupils, like they were swallowing all colour, drinking it all in. And now, the song blaring in the Pieterskerk had taken on new meaning as it swirled in my brain:

And I see your true colours

Shining through

I see your true colours

And that's why I love you

Behind Jan, there was a supermarket carpark. The leaves went by with a gust of wind and a clatter came from the trolley deposit area. A woman yanked at metal chains as dropped coins clinked on the tarmac.

A palette of suburbia surrounded the artist’s bust, verdant hedges, ochre gravel, terracotta bricks, dark slate, black tar, a silver car with an air freshener, the colour of the needles on a spruce pine moved like a pendulum as it went over a bump. A yellow banana’s skin rotting to brown, a lavender bush, an empty blue crisp packet, the dancing leaves, the coins glinting and making music by the rattling trolleys.

Jan’s squinting eyes seemed to open wide for a moment. In my mind his fleshy nose twitched. The wind rose again, and the hedgerows moved side to side like an endless sea until a break in the air, until stillness again. The woman passed with her trolley. The wheels needed oiling; I could hear them squeaking. Nearby, a man revved his hedge trimmer.

In that moment, a street sweeper passed and sucked up the rubbish at the curb in front of the bust, briefly blocking our view of the tavern. The brushes spun and the rubbish disappeared. It moved on and again, Steen resumed his vigil of his old tavern, his grin giving off a sense of great pleasure. The tavern was his muse, he worshiped at the religious altar of pleasure, he made sense of the mess, and that elevates us all.

As I returned to my bicycle, the words painted on the wall of the Lakenhal spring to my mind again: “Memory lives in the most common things.”

A grin, spilling, dripping, chunks of tripe, plucks of a violin, heaven and hell, the dunetop to the estuary, the thief and the schoolgirl, dark browns to luminous yellow, a break in the clouds, concrete and imaginary, memories leaking off the tabletop, flowing like froth onto the floorboards beneath.

Bibliography

*Imagery by author or accessed through lakenhal.nl and nationalgallery.ie

[1] Geert Mak, An Island in Time: The Biography of a Village, (London, Random House UK, 2010), p. 111.

[2] Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (London, University of California Press, 1987), p. 10.

[3] Schama, Embarrassment of Riches, p. 10

[4] Dash, Mike, Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions it Aroused (London: Crown, 2001), pp. 50-53.

[5] Dash, Tulipomania, pp. 195, 226-227.

[6] Piet Bakker, “Jan Steen,” in The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 4th ed., edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Elizabeth Nogrady with Caroline Van Cauwenberge (New York, 2023-), accessed January 25, 2024, https://theleidencollection.com/artists/jan-steen/.

[7] John Walsh, The Drawing Room, (Los Angeles, Getty Museum Study of Art, 1996), 6.

[8] Houbraken cited in Walsh, The Drawing Room, p. 8.

[9] Ibid.