fiction

Full Nine Seconds

Sarp Sozdinler

A writer of Turkish descent, Sarp Sozdinler has been published in Electric Literature, Kenyon Review, Masters Review, DIAGRAM, Normal School, Maudlin House, and American Literary Review, among other places. His stories have been selected or nominated for anthologies (Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, Best Small Fictions, Wigleaf Top 50) and awarded a finalist status at various literary contests, including the 2022 Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction Award. He's currently at work on his first novel in Philadelphia and Amsterdam.

Martin Groch

Martin Groch is a Slovakian graphic designer and illustrator bassed in Brussels. His work merges type, image, and abstract forms.

essay

Traces of past lives: an attempt at capturing balloons

“Can I write about the balloon without attaching too much weight to it? Or is a balloon just a balloon; enough said?”

fiction

The Glass Age

Suddenly, a muffled bang pierced the room. It travelled over the aisles in a shock wave, coating the walls in a shallow echo. A thick silence followed, cut only by the hiss of the refrigerators.

8

min read

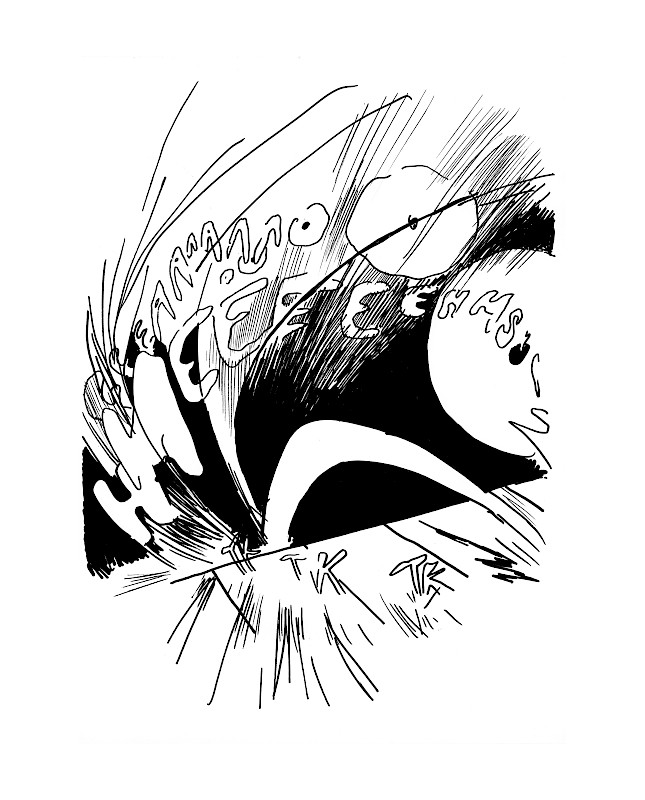

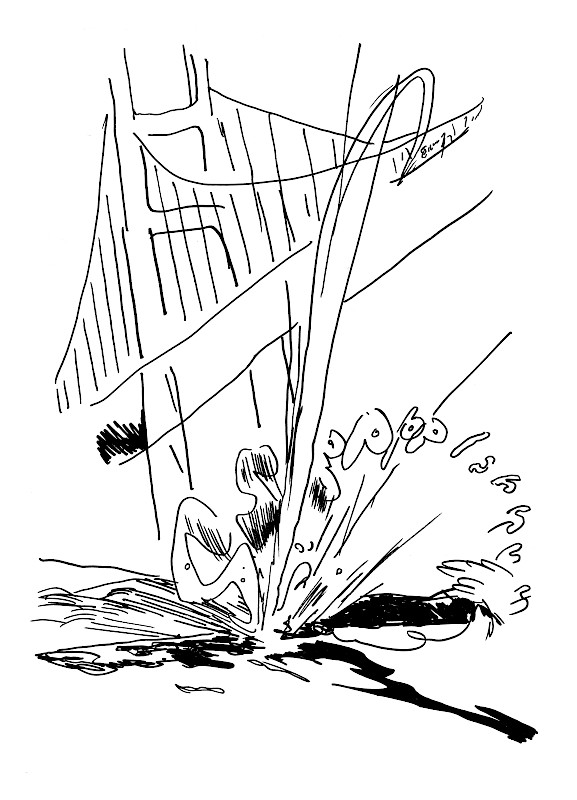

A man plowing through the air: hwwwsssss…

Body hitting a concrete floor: tssssouwww…

Cracking of bones: krrrrkkk-kakkk…

Shattering of glass: krnnncchhhh…

Sirens wailing: eaooo-eaaaooo-eaaaaoooo…

Onlookers screaming: aaaaaaahhh…

Bug imitates each of these sounds with what little capacity his hospital room has to offer. He uses his vocal cords, two hands, and the rounded corners of his lunch tray to reanimate the loudest incident he’s ever experienced: the fall.

——

Bug jumped from the roof of his father’s garage on the night of his seventh birthday and landed on a jutting curbstone. Any dreams he might have had of becoming a professional cyclist by then were crushed that day, along with his legs. At first, the doctors couldn’t tell if he had torn a ligament or broken a bone. Then they could tell it was both. Plural: a few in the ribs and some others around the knees. Bug didn’t cry at the hospital and suppressed his tears until he got back home. And he cried a bit more at school after that. His sisters figured he might be doing it all for attention, for nine weeks had already passed since his discharge from the hospital. They asked their mother for advice, but their mother said there’s no need. She told them the bones would hurt.

“More than the skin,” she said.

The second time Bug broke his legs was two decades after the first incident; he jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge the day after he’d lost his third temp job in less than a year.

He survived somehow, both physically and financially.

“That can happen,” his doctor said, concerning the former. “If you dive in the right angle. If the weather is right. If the tides flow in your favor. If your jacket is wide enough to serve you right as a parachute. You see, the effects of this type of fall aren’t easy to study. Especially through live subjects. You are a lucky case.”

As the attendants hauled Bug onto a gurney, a nurse came over and told him what he’d pulled off was really brave but what the doctor had just explained to him was a fallacy. Bug was in no mood to listen to what the nurse had to say, but the nurse had to say what she had to say anyway. “Each body type,” she said, “each wind shear, even the conditions in each body of water vary too much to take anything for granted, man. Age and fitness could make all the difference.” The whole time she talked, Bug watched the birthmark on her upper lip shift from one shape to another. “Explaining how people survive such a fall is difficult,” the nurse concluded. “I’ll give the doctor that. You were lucky in that sense.”

Luck didn’t land without complications for Bug: he’d woken up having no recollection of the past couple of weeks. (Was it months?) The nurse assured him there wasn’t much to remember. “It was touch and go with you, man,” she said, then added that Bug had survived two surgeries—one for his broken ribs and the other for his knees—the same duo from two decades before.

“What do you mean, touch and go?” Bug wanted to know.

“You know,” the nurse said, “your heart stopped for a full nine seconds.” She figured Bug knew. “Your helmet,” she tried to explain, “spared you a world of hurt.”

Which helmet that was, Bug couldn’t tell.

Bug also had no idea why. Why he ended up there in the first place. What forces of life had lured him toward the edge and dared him to look down. To work up the courage to pull off such a fatal act. His mind and body fought for light and space to come up with a plausible explanation for it all; however, since the surgeries, his insides, like his thoughts, had been functioning like some rearranged furniture and failing to make any sense.

In the next few days, his mind, or what was left of it anyway, was contaminated by this weird unease: an afterthought, so to say, or perhaps the afterthought of an afterthought. It nestled under his skin, lingered deep in the back of his skull. He couldn’t tell whether he’d genuinely wanted to end it all or simply fallen victim to some sort of misunderstanding—a mistake. He wondered if any part of him, any itty-bitty projection of his future self, had objected to the goings-on during the fall and wished to rewind in midair. He wanted to figure out whether he was at fault or if the world was.

Perhaps it was an accident, after all. These did happen, his doctor had told him. How else could over fifteen people die each year from falling off the side of a bed? Eighty from dancing near lava for a mythical goddess they hadn’t met? A hundred from passing out drunk in subzero temperatures? Seventy from swallowing hotdogs whole? And at least as many by eating too long baguettes? Seventeen by tripping over the safety rails in Niagara Falls? Twelve from falling from the garage roof, including Bug’s father. A broken neck: slow and messy. Not only was it devastating for Bug to witness his father’s death as the only remaining male presence in the house, he also worried that it must be particularly hard for his father to watch, from the afterlife, the moment of his body’s discovery: legs scissored backward, neck bent in an uncanny angle; his soul already halfway up the stairway to heaven.

Something had bugged Bug since his father’s death: why did the old man bother with a roof in the first place? Why bother with pebbles and concrete when the Golden Gate stretched into the fog less than a mile away? The sea should be the golden standard for any leap taken into the nothingness, the token of a clean and perfect death, with its easy access by foot, ridiculously frail railings, and improbable heights that promised its lost souls a smoother passage. The waves breaking and washing away all the bones and vital organs in an instant. Until no traces are left.

Yet, he understood that everybody favored a place in the world, even when it came to taking their own lives. Bug and the Golden Gate went way back in that sense. It was the first bridge of his childhood that was attacked by alien octopuses and saved by Superman. It appeared in more movies than he could count, in all those beautifully made black-and-white pictures they used to watch together as father and son every Friday evening, from Vertigo and The Maltese Falcon to Godzilla and The Planet of the Apes. Not to mention, his favorite color blockbuster of all time, Interview with the Vampire. In one of the rarely clear memories of his childhood, he watched Kim Novak commit a technicolor suicide at the foot of the Golden Gate Bridge. Bug didn’t know at the time Novak had something that both he and his father would lack in coming years: a James Stewart (or a Superman) running to rescue.

In the coming weeks of his stay at the hospital, Bug tried to get back on his feet, although his feet acted like a pair of hypocrites, first by turning icy and then like someone was pouring hot embers on them. A deeply radiating prick ate at him for nights as if his toes were being massaged and chopped up at once. In the MRI rooms, he heard the same words from the vocabulary of his childhood parroted over and over — “phalanges” and “metatarsal” and whatnot. He regretted having neglected to look up the meanings of those words for all this time. They still sounded complicated enough, though, he would give the staff that. More so when there was a supporting body language, at which the doctors seemed to have been getting better and better.

“Don’t worry, man,” the nurse tried to calm Bug down in the aftermath of yet another successful operation. “We facelifted your groin and took out your appendix while we were at it.”

With the enthusiasm of a TV chef, she explained how the doctors had grafted Bug’s muscle tissue and sliced a part of his tibia to graft into the crushed bones in his legs. She added that they didn’t forget to put in a metal rod from the knee down. She sounded proud the whole time she talked. Looked it, too.

She waited for Bug to say thanks in some way, but the words didn’t arrive.

“You know, man,” she then concluded. “The trick is to not worry too much.”

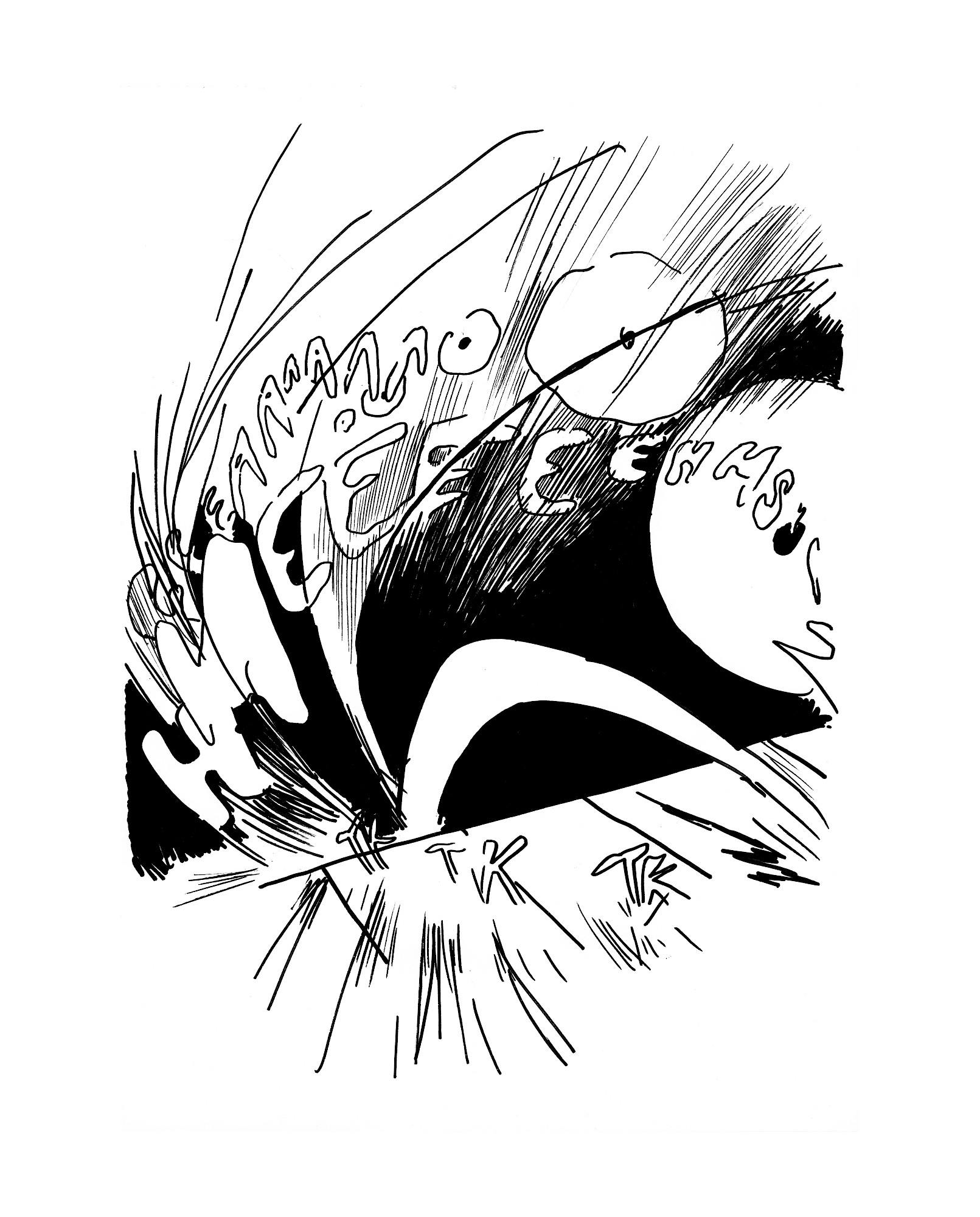

Bug nodded blankly although he had no clue why. He got up from his bed and limped over to the window. He glanced down at the yard under, then back at the nurse, then out again, and back and forth for a while before one of his feet finally followed the other off the railings and into the air.

For a full nine seconds.

krrrrkkk-kakkk… •