interview

Learning Space

Maia Kenney

Maia Kenney is an art historian, curator and critic specialised in feminist underpinnings of modernist art movements (and a proponent of the destruction of Modernism as a Eurocentric storytelling device). She is the digital curator and editor of The Couch, and teaches theory in the Master of Contextual Design at Design Academy Eindhoven.

letter

Editor's Note

letter

A letter from my couch

2023 in review, and a few hints on what’s in store for The Couch in 2024.

essay

Mystics of the Chthulucene

Cthulhu – H.P. Lovecraft’s science fiction monster – lurks under the surface of the ocean as an elemental deity. We must wonder what lurks beneath the surface of the systems known as AI.

13

min read

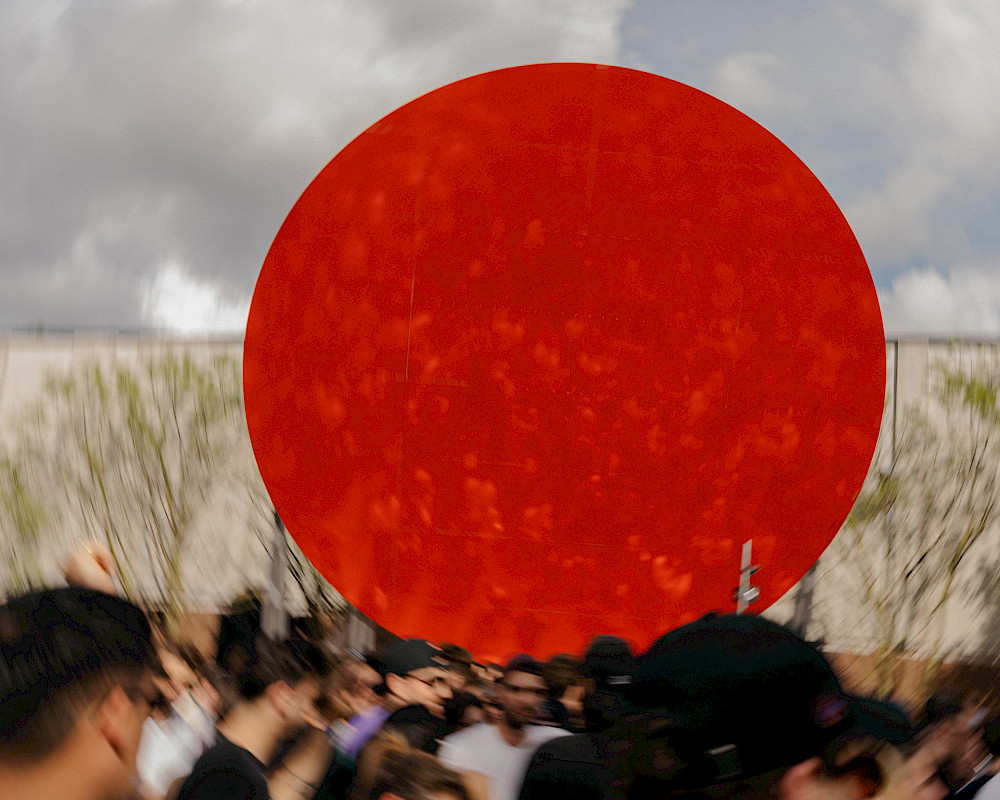

"We are learning by doing, always looking for possibilities."

Since Het HEM opened in 2019, it has had a robust and ever-changing music programme. What started with listening sessions in the Dynamic Range Music Bar in the basement, quickly developed into live shows throughout the rest of the building; artistic residencies investigating the relationship between sound and the architecture; and epic pop-up events like Sleep In: Slow Wave Phase and the Dance of Urgency event during the Covid-19 pandemic. Het HEM is now entering a new phase of its existence, in which we explore the potential of music and arts programming in the digital sphere. Alongside the unveiling of Brian d’Souza’s newly commissioned artwork Genius Loci, we are taking the time to say a temporary farewell to the building. We want to understand what happens to Het HEM’s identity as it shifts from the physical to the digital.

In this interview, Het HEM music curator Orpheu de Jong and The Couch curator Maia Kenney talk about Het HEM’s music programme and its relationship with the building's architecture. They discuss the importance of exploring the building through sound and music and the potential for new directions in the digital space of The Couch. What happens when curators and programmers let go of their ego when working with artists? When they embrace failure?

Maia: Orpheu, I wanted to ask you about the reason why there's so much research into the link between architecture and sound in Het HEM's building.

Orpheu: I think it's good to go back to the beginning, when I first started at Het HEM. Initially, the music programme was mainly in the Dynamic Range Music Bar in the basement of the building. And that was a great starting point, you know, having a dedicated place for music within the building. And even though we already started looking for ways to bring the music programme and the Chapter programme together during Chapter 1NE, it wasn't until Chapter 2WO that we really started embracing the possibilities of music within the building and its new function as a home for contemporary culture.

The Guest for Chapter 2WO, Nicolás Jaar, almost approached the Chapter as a residency and took the liberty of trying out many different things in the building. At the same time, that gave me as the music curator a lot more freedom to explore, to try new things. So after our first period of getting the building set up for the opening, we started getting acquainted with the spaces and looking around. There were so many options, so many things to try out. I started thinking in an almost choreographic way about music inside this building. From the basement, music started moving out into the building, onto the factory floor and beyond. We looked at how people would experience music if they were not static, in one room, but if they moved throughout the whole building following a programme that manifested itself space by space.

Maia: Wish I could’ve been there.

Orpheu: During that period, the music programme took shape more and more, it started to work… But then the pandemic hit, so trying things out and exploring possibilities (and impossibilities) became even more urgent. The transition into the reality of Covid-19 changed everything. All of a sudden we had a highly useful commodity: space. Lots of it.

Thinking practically, we moved the music from the basement, with its limited space, up to the spacious ground floor. And artistically, we needed to get a grip on music as part of our programme, so we decided to put music both at the centre of the programme – and of the building. Since we had so much space, we could spread out and still do listening sessions or seated live performances. At the same time, artists were restricted from traveling and performing. Being thrown back into their studios, many were left with the question: what creative steps could they take now? We started thinking about how we could provide musicians working across many disciplines with the opportunity – the time – to focus, to explore an interdisciplinary way of working. So in a way it was also a practical reaction to the musicians’ reality.

It was still part of the exploring phase: getting to know this space and seeing what we can do here. I think that's why reacting to and exploring the building at the same time has been quite important in these formative years.

Maia: It almost feels like there’s an infinite number of ways to explore Het HEM through sound, through music, through dance, where the space isn't just a passive location for music programming but an ecosystem. I’m thinking of Bogomir Doringer's Dance of Urgency event in 2020, where people could come together to dance in circles drawn on the ground despite having to social distance.

Orpheu: That was a great moment, because it gave us the realisation that we had quite some options with so much space. We had all these square meters – a luxury, because we could have an event where 100 people could dance while still following lockdown regulations. This first period, with its possibilities and temporary limitations, has been about learning about this building and its relationship with music, and about how to use it, play with it, draw from it.

Maia: I didn't realise any of that, actually. I think it's fascinating that the physicality of the building itself also guided the process naturally, until you had a space that draws people in. It's also amazing that a small and very intimate turntable and speaker system in the middle of this absolutely enormous hall is still the centre of the whole space. Coming in there on a quiet Sunday night, you're drawn to the music, to the story that it's telling.

Orpheu: Especially in that first period when we started exploring, it was helpful to work and think along with a musician about what’s the best way – the best space – to present their work. That also helped us understand the building and how to use it. It has a very different function than its original one as a busy factory, and there were only minimal changes made to it when we - Het HEM - moved in. It is a learning process, even with the public programme or with the exhibitions, to figure out what, where and how to present.

Maia: So was there a clear shift from learning about the building through presenting and making a space for music and listening to more open-ended sonic research? Or was it a simultaneous process?

Orpheu: Simultaneous. It triggered learning how to present both in the context of an art space and in the context of this specific building. We tried to learn about the building itself, too, but the conceptual structure you present in is also important. From there, we started looking at different aspects of music in relation to space.

For example, in their Re.Sounding research project, Pamela Jordan and Sergio González Cuervo looked at how sounds echoing around the various rooms in the building could become a way to reach back in time, to when Het HEM was an active manufacturing site. They are curious about how our senses can be triggered to understand how people used a space historically. It's not so much about music, but more about how to preserve an architectural space through sounds. That's something that ties into our Spatial Range project, which is a project in some way about site specific music: music not necessarily presented in a specific space, but music made for, or even with, a specific space.

Maia: Obviously we're closed for the next year, and we’re putting our energies into The Couch…

Orpheu: I have the feeling that now that we have this break from the building, it's fun to think beyond researching the building. We know a lot now; we can take what we’ve learned into a new dimension. It's interesting to go deeper into music’s relationship to the topics that we explore, like this shift we’re undergoing, from a physical to digital space. And I think now we can form a synergy between different programmes.

Maia: What was the most interesting outcome that you've seen so far from all of this creation, research and experimentation that's been going on?

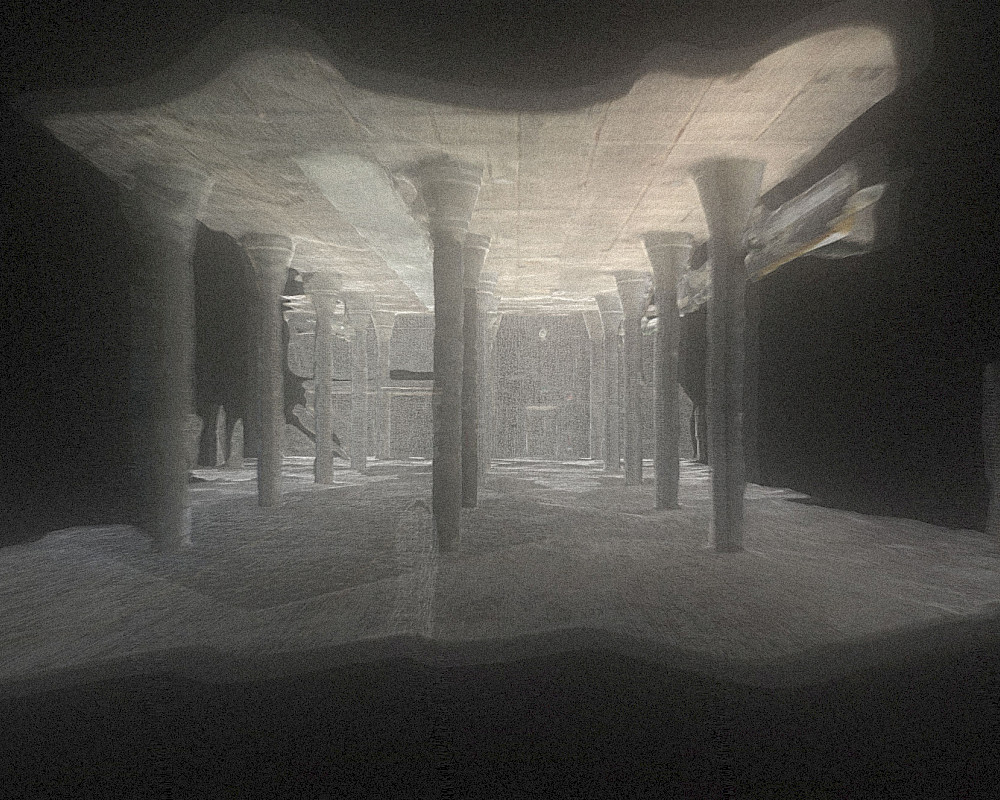

Orpheu: Well, Pamela and Sergio’s research is ongoing, but it shows us how the history of a place still exists though the act of listening. Seeing a historical perspective through sound evokes questions such as what can you learn from listening to this space. In a different way, Brian d’Souza’s artwork, Genius Loci, is similar because he tried to grasp the spirit of the space not only by listening to it, but by filling it with sound using one instrument, the accordion. If you watch the artwork, the sound of the accordion seems to be communicating with the architecture.

Maia: Why did you choose Brian as the first artist that we're commissioning work from for The Couch?

Orpheu: What I think is really interesting about Brian is that he has done a few projects before that are continuous playback formats, like his radio station, Ambient Flo. For his project beacon.black, he sonically explored a military site in the UK. He made a beautiful soundscape and audiovisual work by capturing the remnants of a landscape that had been forever altered by humans. In light of us trying to learn about Het HEM’s building, which is of course also related to a military history, it was too perfect not to invite Brian to take this research further. In a way, I see Brian’s work as rounding off this era. It is not the end, but it is closing the circle – we have explored the building with all kinds of performances and projects. We had musicians creating music in and for the space; we had researchers exploring the space through sound. And we now have an artist capturing the spirit of this space and making an audio work that is specifically designed to be experienced online. We really explored the building from top to bottom, physically and metaphysically.

Maia: What do you see coming out of Brian's work? Will it lead to new directions for us to explore space in our new project The Couch or other future programming?

Orpheu: I think it really captures the sense of the space. That’s also the title, Genius Loci, the spirit, character or atmosphere of the space, which it describes. I think it's a beautiful moment to try and show that spirit of the building because you can’t be here now.

Maia: Is this a transitional moment?

Orpheu: Sure, it is. We present to you a work that gives you an artistic view on the essence of the factory - its past, present and future. It's an impression of the space, like a memory. It's not exact, it's a certain approach to this architectural structure, which together with the music that comes from these spaces is very present, very beautiful. The timing is perfect.

Maia: You've been working in music your whole life. What do you look for in a project like this? What interests you most, does it always change?

Orpheu: Music is a never-ending source of directions that you can take, and my interests have shifted over time, that's for sure. Speaking specifically of Het HEM, it really started with how we can create a warm nest for music within this huge concrete building. How can we present music in a complete way by having people take a seat and listen properly, take their time? How can we provide an alternative to the fast-paced side of presenting and consuming music? And now, in the coming years, we will explore time and how it relates to the programme. And how we can present music as completely integrated into our other programmes. I think those are the goals for the coming years. How do people give time, take time or experience time?

Maia: I’m curious how – or if – we will be able to find equal footing for sound art and for music.

Orpheu: It's like a natural development, because yes, we know music is part of this, but we're still exploring the how. We are learning by doing, always looking for possibilities.

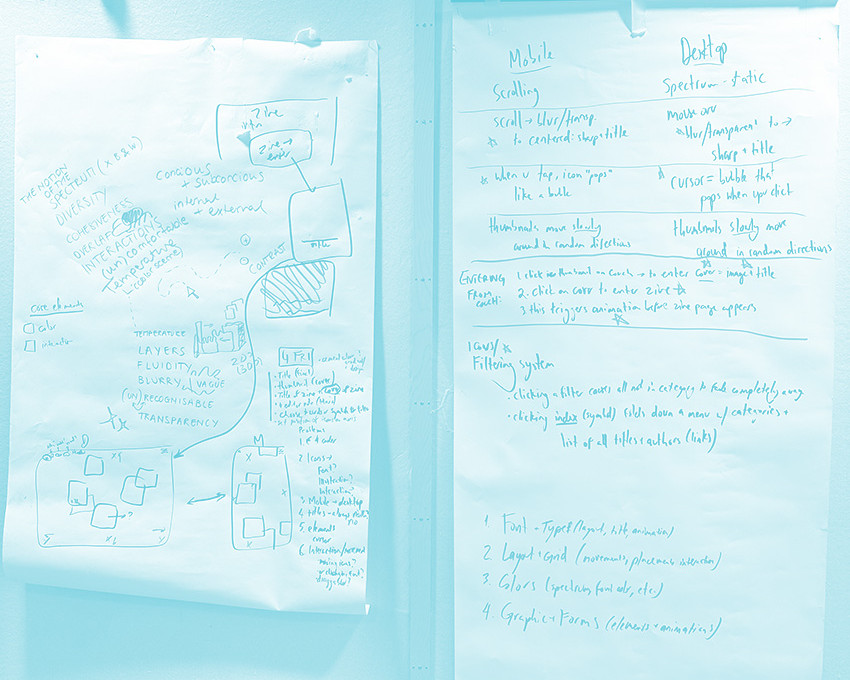

Maia: Now with The Couch it's like a new starting point, in a sense. We have an entirely new platform and we have to deal with questions again that we've carefully found answers to or directions for within the actual building. And Brian's work does open that door. But what would you want to see on The Couch in terms of a relationship between music, sound art and the visual arts that now we're also exploring in terms of this digital space?

Orpheu: We are trying a lot of new things on The Couch. I think it's a good opportunity to create layers that are not there yet in our physical programming and go deep on certain topics, people and projects. The same for music: if we can figure out how to give more context to certain things, topics, pieces, artists, and then find a way for people to give their time to us, and if we can fill that time in a unique way, I think that would be great.

Maia: Something that addresses a niche but doesn't lock you into one, so you can start to make connections yourself.

Orpheu: Definitely, and at the same time kick the fence a bit.

Maia: I was just thinking about how to keep the voice of the artist present - or as present as we can make it. It is a huge task to always center the person who is creating. I'm wondering how you approach that with the musicians you invited to research at Het HEM?

Orpheu: There's certain topics that we gravitate to, but within these topics or the directions that we are exploring there's complete freedom in what the artists do. We don't ask them to research a certain topic, it's more that we feel that what the artist chooses to do helps us in understanding these topics and that we can learn from it. I don't have an ego that decides what it should be, or what form it should take, as a predetermined story arc where you tell the story through specific pieces or artists. It's way looser. That's why it's also important that we have makers in the building, who shoot, make, present and meet the audience in the building. It's not just about playing a tune, it's really about what we are doing in this space, how we can make new things happen in, or from, this space.

Maia: So is there a next step specifically? What do you want to explore or research; what are you curious about at the moment?

Orpheu: At the moment, I’m obsessed with dub, mostly as a de- and reconstructive process across genres. In relation to time, but in certain ways also in relation to space. The mechanics of dub and the underlying (social) history and influence of it is something that interests me a lot currently, especially with us not having a space and exploring time as the next phase of research. Let's see where this will take us...