essay

Two Nights of Noise at Tivoli

Charlie Jermyn

Charlie Jermyn is a writer, essayist and performer from Dublin living in Amsterdam. His works include aural odysseys on landscape and art, the dissolution of bowling alleys, perambulation across nations, and travel writing from Balkbrug to Hong Kong, Dublin to Pavia. He is a monthly resident at Stranded FM Utrecht with his show More Poetry is Needed, where he has explored the poetic works of Arthur Russell, John Cooper Clarke and Van Morrison.

essay

A neon palindrome, lessons from the crouching man

“In the name of contemporary art, Spain has finally embraced the whitewash technique of the iconoclasts.“

essay

The distant bungee jumper, a dangling herring

Charlie Jermyn was on a mission to discover the history of the North Sea resort town of Scheveningen. The essay tracks Charlie’s disorientating pilgrimage through a haze of mystical sea creatures, marshland, beached whales, kibbling, hungry gulls, and bungee jumpers.

essay

A devilish grin, a suburban carpark

Essayist and poet Charlie Jermyn makes a do-it-yourself pilgrimage through museum, muck, rain, wind and pub to visit Jan Steen’s old haunts

Kalle Mattsson

Kalle Mattsson is a Stockholm based graphic designer, illustrator, animator and some sort of graphic comedian, which he would like to take this opportunity to apologize for.

essay

A devilish grin, a suburban carpark

Essayist and poet Charlie Jermyn makes a do-it-yourself pilgrimage through museum, muck, rain, wind and pub to visit Jan Steen’s old haunts

column

You Gotta Serve Somebody

“Hello” I typed, and it felt like flinging sound into a cave, testing to see if someone was there in the dark, some being of an undetermined image.

column

You Wanna Know How We Got These Scars?

Writer, cultural critic, and philosopher Ben Shai van der Wal calls upon us to embrace our trickster-friend. A short essay about how society’s need for healing and fixing stands in the way of it.

17

min read

"And the old, still howling like vultures, still barking like dogs, still stomping bare feet, still revving the drill, still testing the foundations."

In late November 2022, I was in Utrecht, passing time before going into Tivoli for a concert by Einstürzende Neubauten. The fog was heavy and hovering with stubbornness as I wandered from the old canal banks of the centre through to the modern indoor mall, with its large-scale eateries surrounded by the construction sites circling the station. The lamplight struggled to make any progress through the dense and dark air. I had been to the venue only once before, earlier in 2022, at the end of June, to see Iggy Pop.

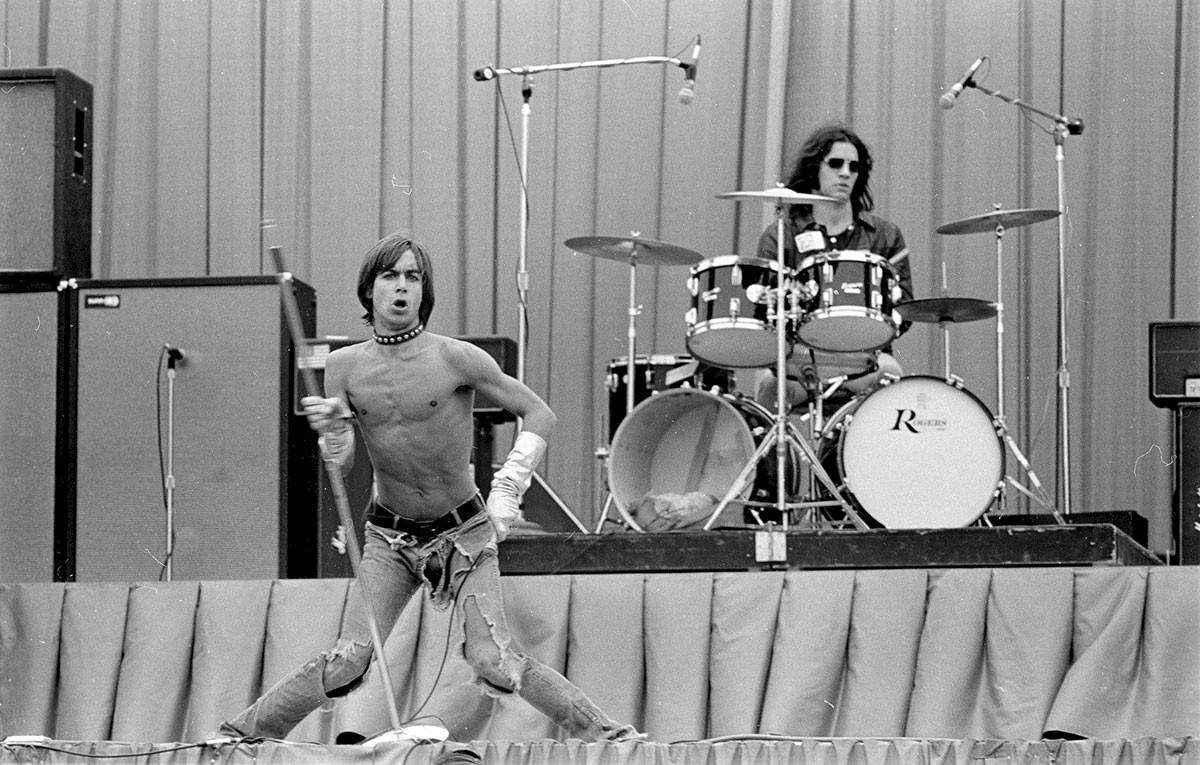

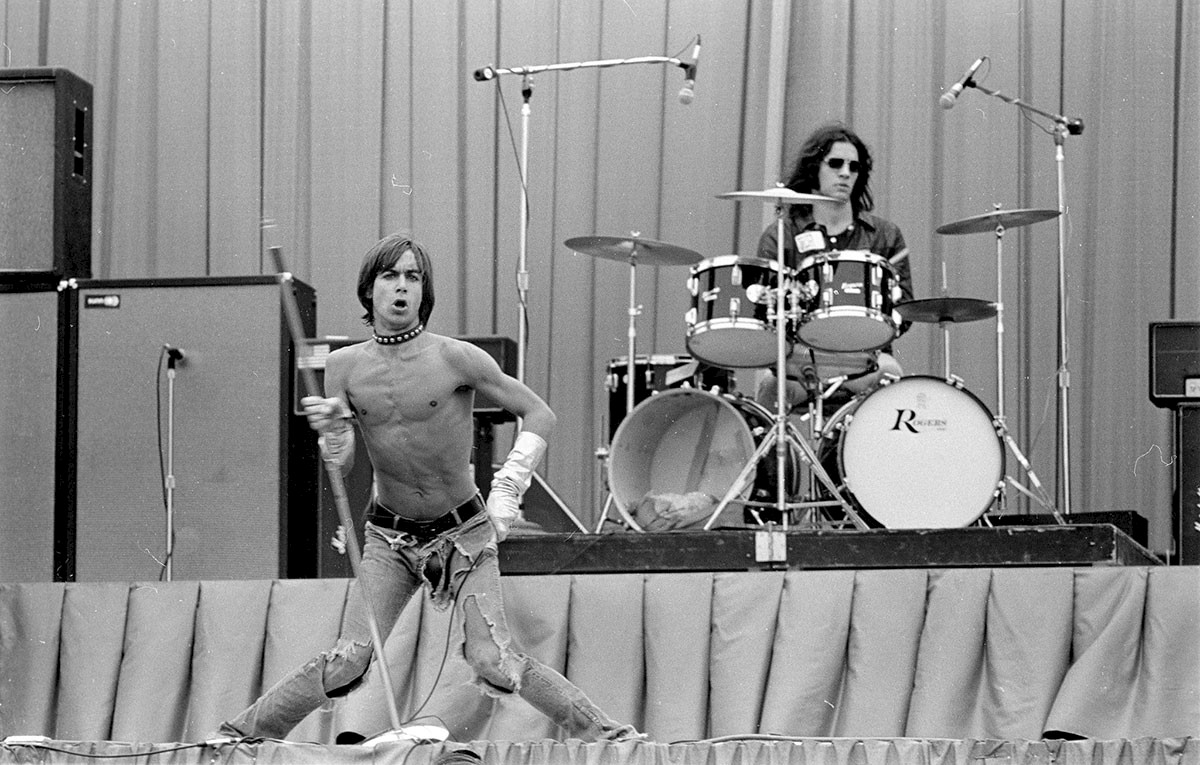

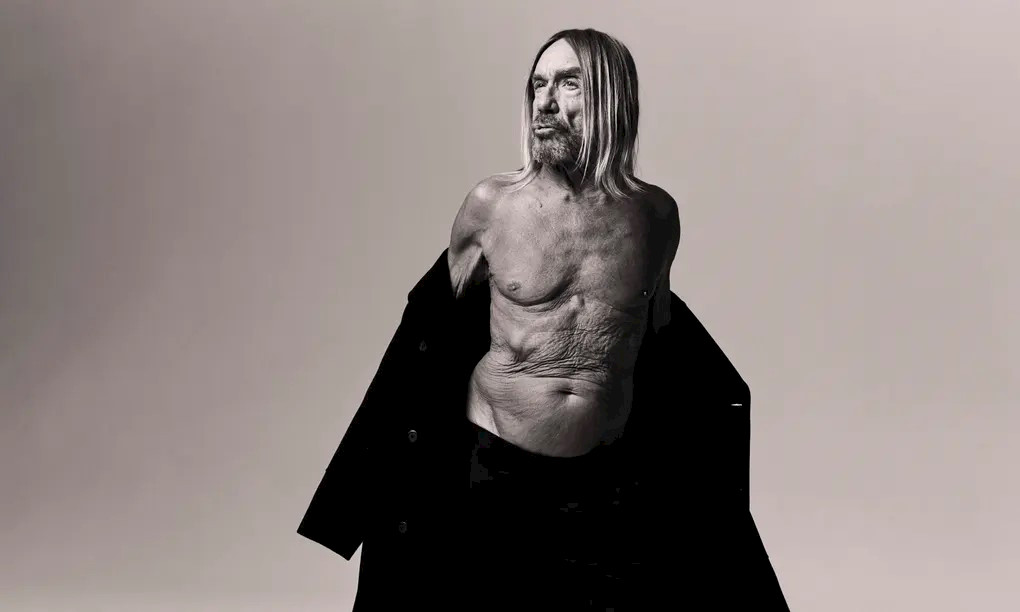

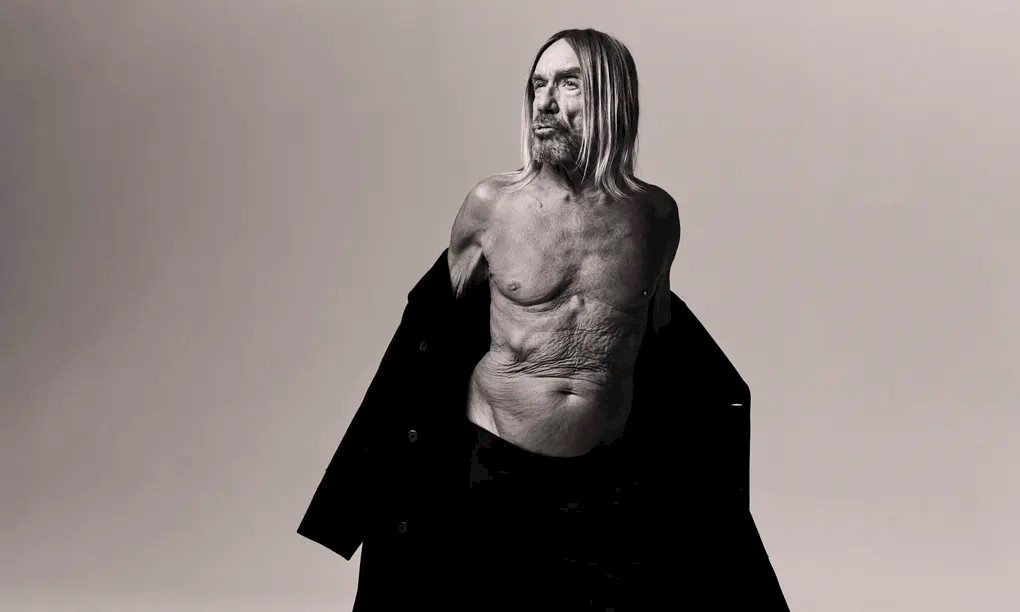

Iggy Pop at the Tivoli Utrecht

June 22nd 2022

There was no fog. Terraces were full of diners. I remember sweating on the train. The crowd pouring into the venue were a mixture of aged punks in faded t-shirts, spun about in the washing machine for decades, and young moshers eager to thunder themselves into a maelstrom of partially nude humanity before a partially nude god.

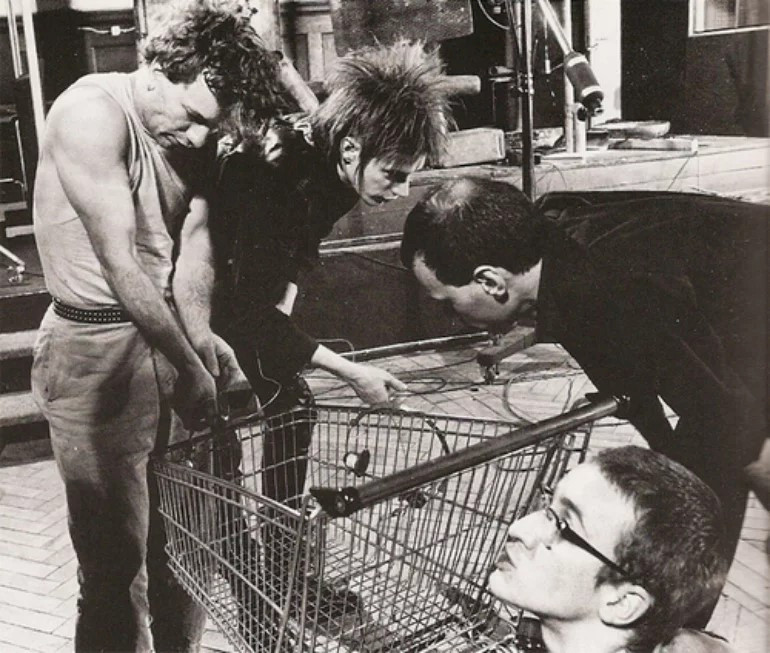

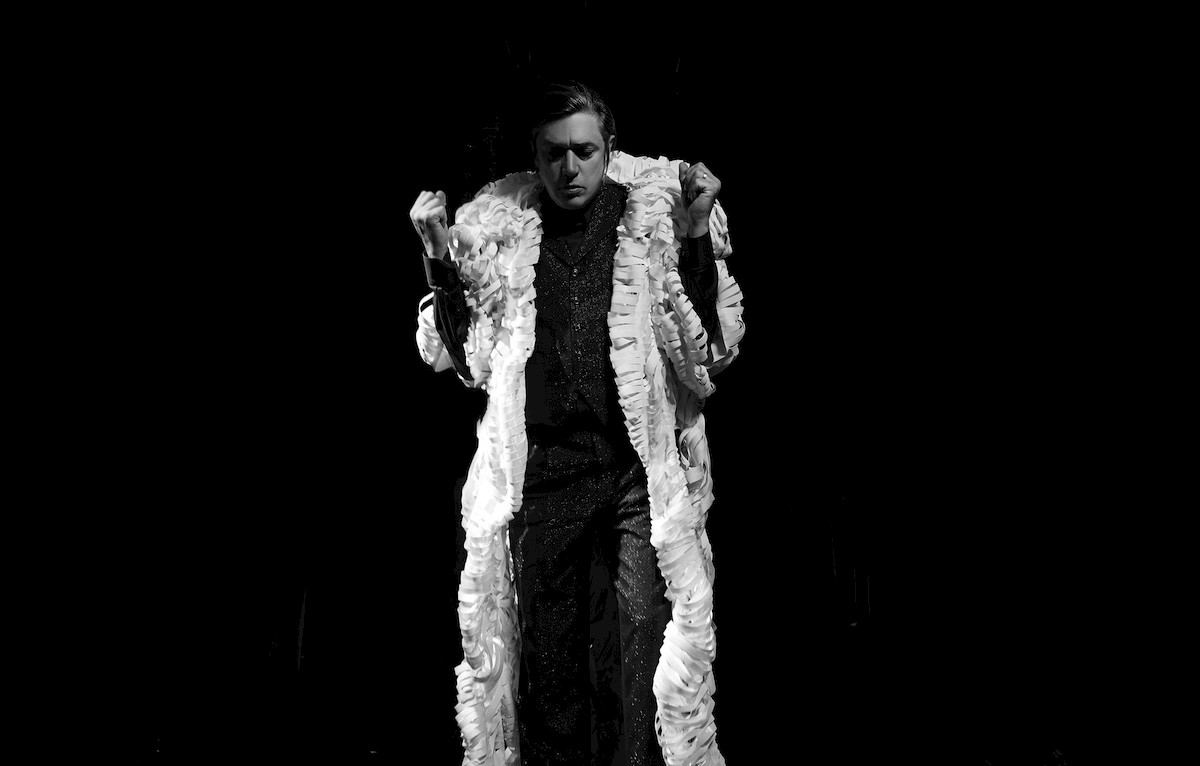

Iggy, wearing a black blazer, rushed on in a limp to the song Five Foot One. He rapidly tore off the blazer, whipped it above his head and threw it off stage. The man famously revels in revealing his chest, a look he adopted from films depicting the ancient Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt that he admired in his youth. At seventy-five years old (now 76), the man can move. He wore a bandolier of veins across his torso. As the opening song implies, Iggy is small in stature, his limp due to an inch-and-a-half difference in the length of his legs. He blames this on an old football injury and on subsequent struggles with arthritis.

Iggy’s hair was oily and straggled. His face seemed carved from the polished wood of a totem pole dug up from the earth. The band played on, with his voice that of a fragile aged rockstar in Loves Missing then shrill screaming in T.V. Eye, and into Endless Sea. Sloshing beats coming from a distant horizon, ebbing, flowing, a call of the siren up on stage. In between the howls to the heavens and the slapping of the snare, he looked directly at me, his eyes an intense ocean blue, deep at the centre.

The mega clang

Iggy Pop’s real name is James (Jim) Newell Osterberg Junior, and he was born in 1947. Jim Jarmusch’s 2016 documentary Gimme Danger opens with the documentarian interrogating Osterberg about the invention of Iggy and the birth of the Stooges in an undisclosed location beside washing machines and domestic detritus. The green leaves of trees blow in the wind, framing his shoulders through the windows. His eyebrows move up and down. The viewer is shown archival footage from the years of Osterberg’s early life growing up in Michigan.

As a boy, Iggy lived in a trailer with his family. He couldn’t squeeze his drum kit into his shoebox of a room as there was only space for a bed and small desk. His parents initially let him play in the living room. The trailer would seesaw from side to side. Eventually, they gave him the master bedroom, stating it the “lesser of two tortures.”

In the interview with Jarmusch, Osterberg reflects on a school trip around the age of ten:

When I was in fourth grade, they took us to the River Rouge assembly plant of the Ford Motor Company and they had a machine that engineered a controlled drop of a piece of metal onto a stamping plate and every time that they hit the stamping plate it made just a racket, just a mega clang. I liked the mega clang.

Grainy footage of the slamming contraption overlay the voice, then red rivers of molten metal flow down into troughs, separating into veins, steam rising, hissing as it meets water.

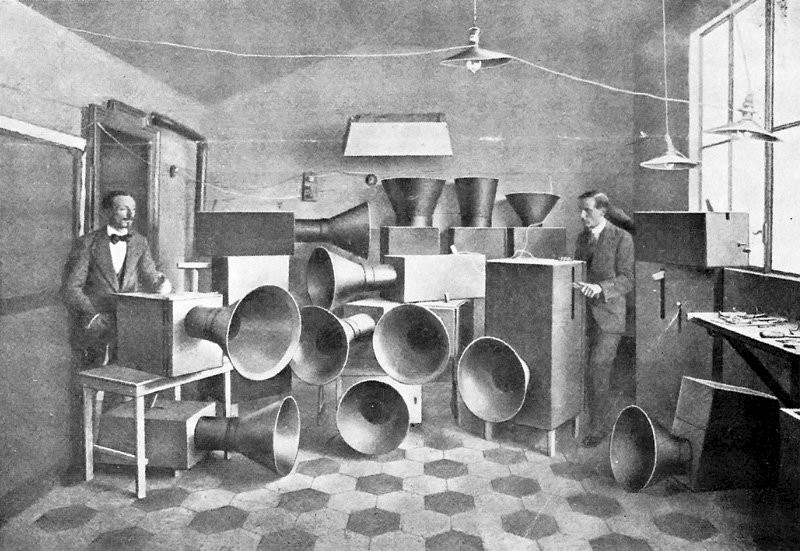

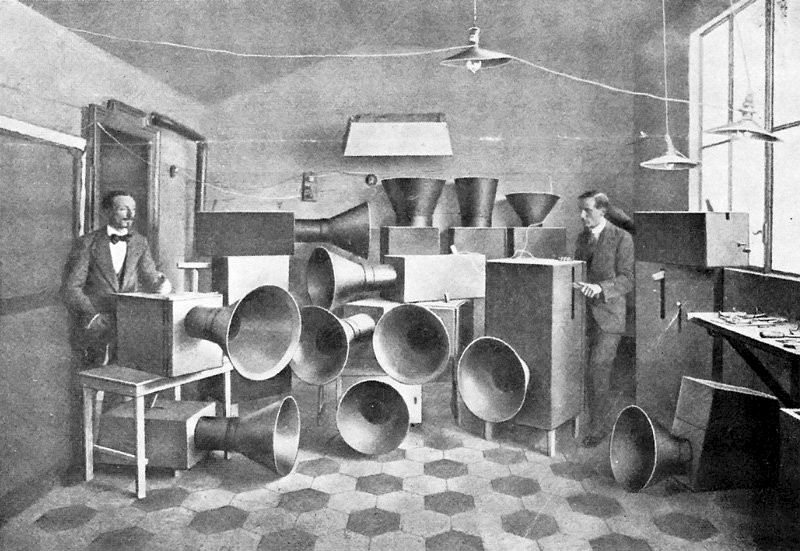

The Stooges were formed in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Immediately, they were on a sonic mission to reach the echoing repetition of the mega clang and the great pumping factory machines of greater Detroit. The Stooges played primitive riffs; they battered oil drums with mallets. There was always a blender around. They dangled high feedback microphones into barrels and the cones of gramophones, slowly dropping them into the narrowing dark as the octaves lowered too, disappearing deeper and deeper.

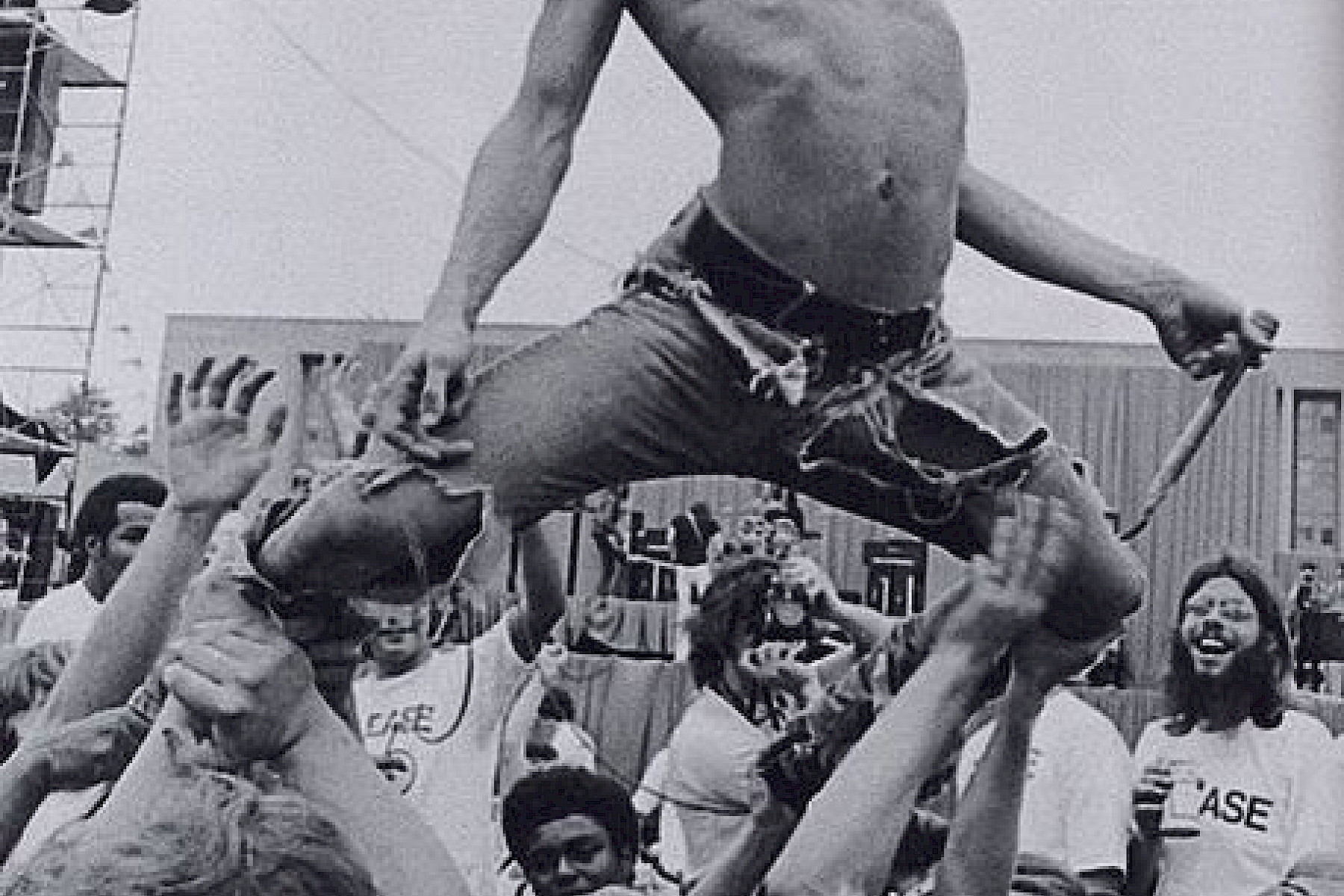

It is said that Iggy invented the stage dive. On his maiden flight, the crowd parted like the Red Sea. The floor met his face, and his front teeth went through his upper lip. Rivers of crimson cascaded down his chin. Those responsible for his teeth now should be honoured in some way, today they look robust, shining pearl-like against his leathered skin.

On the stage in Utrecht, Iggy played Mass Production: A fog horn, a pneumatic noise, a pleading, tired voice, see the smokestacks melting, a sledgehammer grinding it all down. It feels this song was moulded on that school trip to the Ford Motor Company in the early 50s: An anthem to the mega clang. The noises cranking out from factories.

Then, the classics: The Passenger and Lust for Life; on stage, Iggy playfully pulled down his tight trousers to reveal the shallow valley of his upper arse crack. He fell to his knees. Down on the ground, crumpled up in a ball, he put the microphone in his mouth and barked like a dog, and then said, “Back when I was in the Stooges, I was young, broke and dirty.” He breathed heavily into the microphone before whispering, “And I’m still dirty.” I Wanna Be Your Dog began to play. The aged reflective rock star, stubbornly, beautifully hanging around like fog on that black Dutch canal.

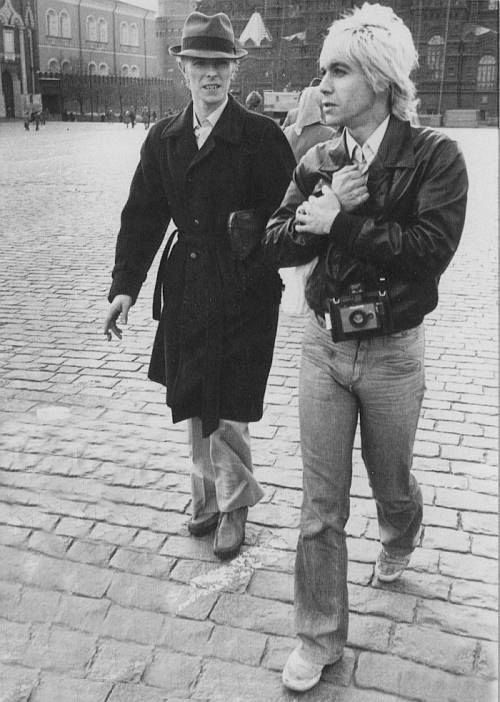

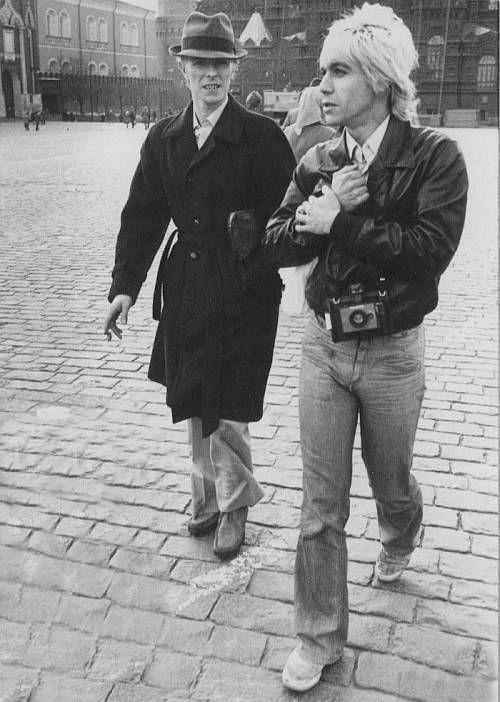

After three albums, The Stooges ground to a halt, drugs bringing the exhaustion of ambition. Iggy moved on to Europe and Berlin and David Bowie. Bowie and Iggy, off the drugs, for the most part, had a prolific relationship in Berlin, living for a period together on a tree-lined boulevard in West Berlin in the 70s. Bowie made Low, and Iggy made Lust for Life, produced by Bowie in Hansa Studios. Nick Cave, Depeche Mode, and U2 followed in their footsteps to record and find inspiration in the city divided.

Noise, cacophonous noise, defined the music of The Stooges and Iggy has forever since, pushed the boundaries of sonic creation spanning genres armed with his iconic voice. In fact, Iggy prides himself on being someone who helped wipe out the 60s, always facing forward, leaping into the unknown, hoping someone might reach up and catch him.

The Art of Noise

The founder of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, wrote the Futurist Manifesto, and it was published on the front page of Le Figaro on 20 February 1909. The manifesto ignited a movement in the industrial north of Italy. Marinetti called for the burning down of museums, libraries and academies, for the worship of race cars and the beauty of speed, for smashing the mysterious doors of the impossible and for singing for the love of danger – all written and delivered with a passionate intensity. Futurism believed in a fresh start for everything, artistically, politically, socially, and historically. A ceaseless turning wheel of creative destruction: the fetishisation of the new and the denial of the past.

The movement leaked into many facets of artistry and lifestyle: paintings by Giacomo Dalla of dachshunds waddling on stumpy legs, leash whipping; Umberto Boccioni’s sculpture ‘Unique Forms of Continuity in Space’; the architecture of Antonia Sant’Elia and the design of a Futurist metropolis, also in theatre, montage, film, and fashion.

There is a Futurist cookbook featuring new methods of alimentary preparation and consumption, where absurd dishes were prepared to counter the sluggish influence of pastasciutta, the doughy stodge of traditional Italian cuisine. In 1910, a great Futurist meeting was held at the Politeama Rosetti in Trieste. The absurd dinner served after the meeting – which inversely began with dessert and ended with appetizers in classic Futurist style - shows many of the Futurist’s obsessions:

Coffee

Sweet memories frappés

Fruit of the future

Marmalade of the glorious dead

Roast mummies with professors' livers

Archaeological salad

Stew of the past with explosive peas in historical sauce

Fish from the Dead Sea

Lumps of blood in broth

Demolition starters

Vermouth (1)

The Futurist hunger for such curious dishes was equal to their hunger for ceaseless modernisation.

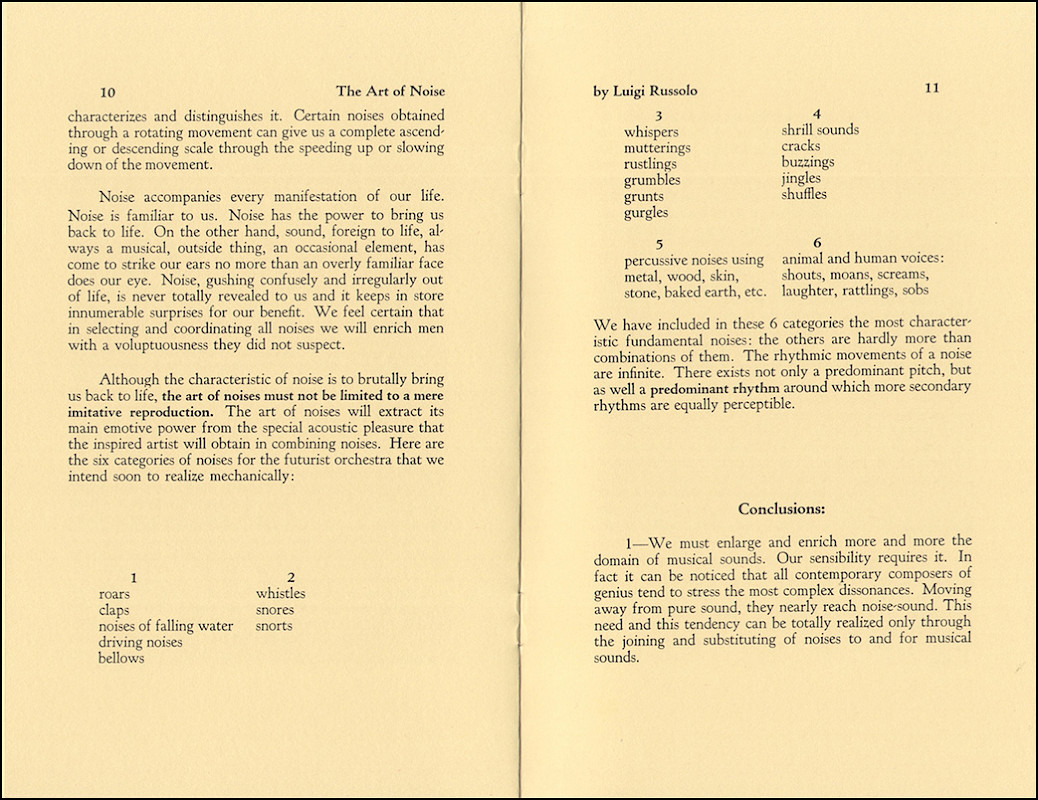

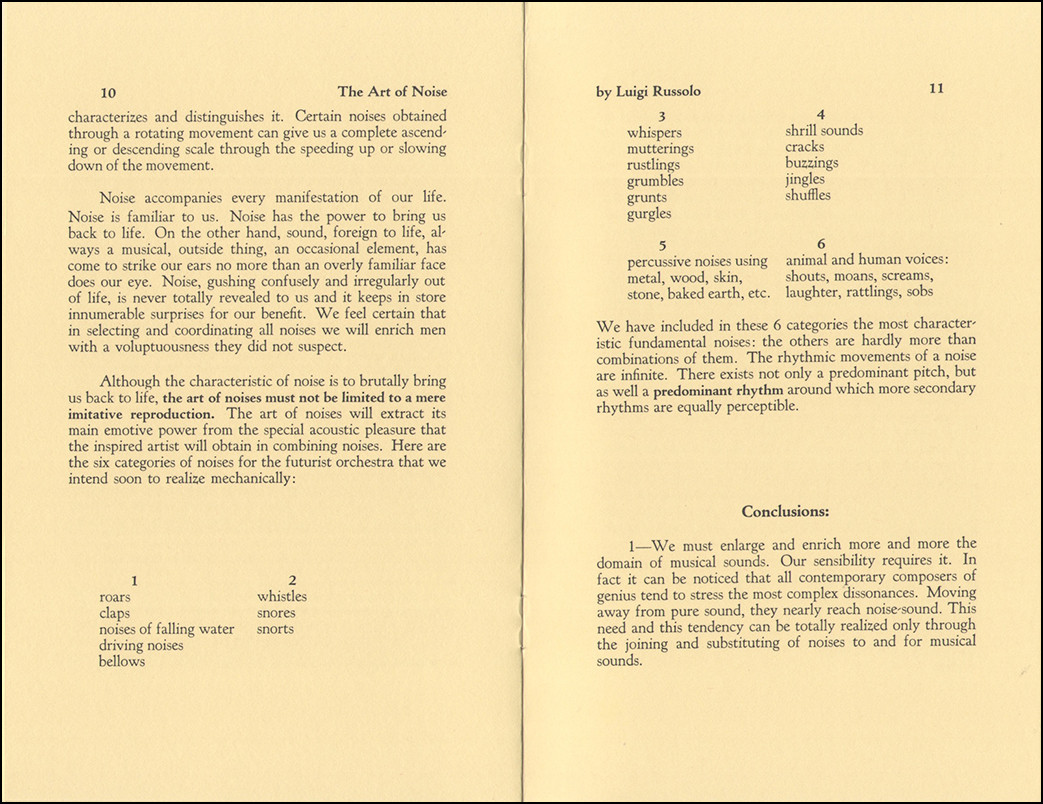

Luigi Russolo, a painter turned composer, was a part of this accelerative, future-obsessed cultural movement. Russolo’s futurist manifesto, The Art of Noise (L'Arte dei Rumori) was published in Milan on March 11, 1913.

In The Art of Noise Russolo wrote, “Ancient life was all silence. In the 19th Century, with the invention of machines, Noise was born.” Russolo believed that in ancient times, where music was scarce, any noise from any sort of instrument, natural or created, was deemed a thing manufactured by the divine. Noise was primitive and ritualistic. Russolo defined this as Intonarumori, noise-sounds. The concept is based on the purity of sounds that comes from the simple everyday objects, nature and the physical human body: The whistling of a plucked riverside reed, the clacking of branches, the clapping of thunder, the stamping of bare feet on caked mud. All noises can be part of an overall symphony. And urbanity created more everyday musicality, Russolo says:

This evolution of music is comparable to the multiplication of machines, which everywhere collaborate with man. Not only in the noisy atmosphere of the great cities, but even in the country, which until yesterday was normally silent. Today the machine has created such a variety and contention of noises that pure sound in its slightness and monotony no longer provokes emotion.

Russolo and Marinetti gave the first concert of Futurist music, complete with intonarumori, machines that scream, in April 1914. A massive riot broke out.

Einstürzende Neubauten at the Tivoli

Monday 28th November 2022

Collapsing new buildings

Like Iggy Pop, Einstürzende Neubauten also spent time recording in the historic early twentieth-century ballroom of Hansa. I first read the name Einstürzende Neubauten on the residential building where the Haçienda of Manchester once stood. The timeline of the building’s demise was carved into the metal grating outside, lining the walls:

The Haçienda opens May 21, 1982 Bernhard Manning.

1982 New Order, Boy George, Simple Minds

1985 Einstürzende Neubauten banned after attack on cast iron columns with a pneumatic drill, The Stone Roses, The Pogues, The Associates

1992 Take That, Factory Records collapses.

1998 The Haçienda demolished

I particularly enjoy the fact that Take That seemed to be somewhat blamed for the ultimate dissolution of the structure. The boyband revving the final drills in the cast iron columns. The tremors felt in the foundations. Einstürzende Neubauten means Collapsing New Buildings, and the band were formed in West Berlin in 1980. The group was obsessed with destruction and renewal and lived up to these themes in their stage performances and art, sometimes referred to as sensorily overwhelming creations. I read that Blixa Bargeld, the lead singer, lived on the same street as Iggy in Berlin. Perhaps they passed each other on the way to the hardware store, searching for sonic inspiration in the mechanical.

Fellow Germans Kraftwerk produced the music of the future: Europe, the noises of the motorway and the orchestral beauty of the sounds of the factory. Whereas Einstürzende Neubauten produced music that moves from harsh, eardrum-rattling clatters to stunning, metallic euphoria. The symphonies and melodies they release are of the defunct post-industrial factory, the scrapyard, the overgrown hinterlands along the Autobahn where burned-out Trabants, twisted engines and rusted radiators become the tools of composition.

Waste and scrap are not in Einstürzende Neubauten’s vocabulary: they find use in the useless, opportunity in the derelict.

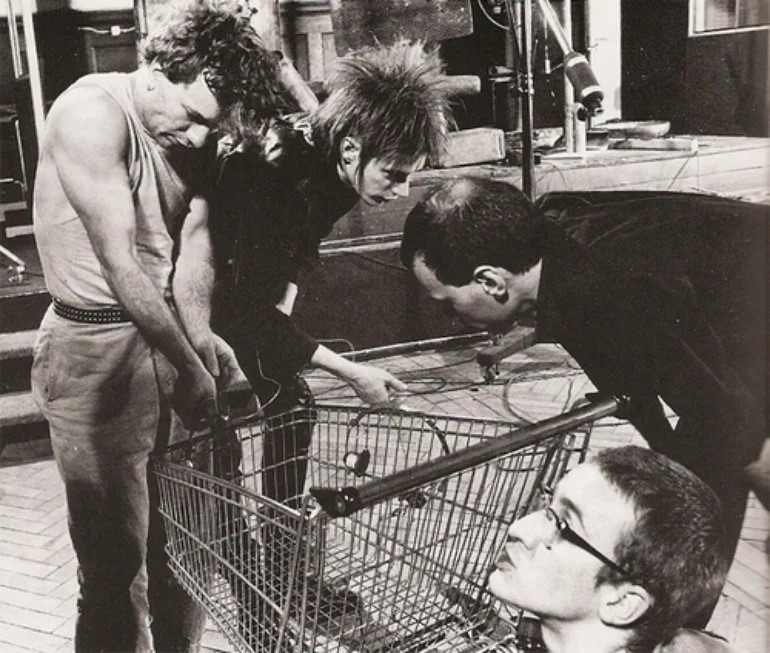

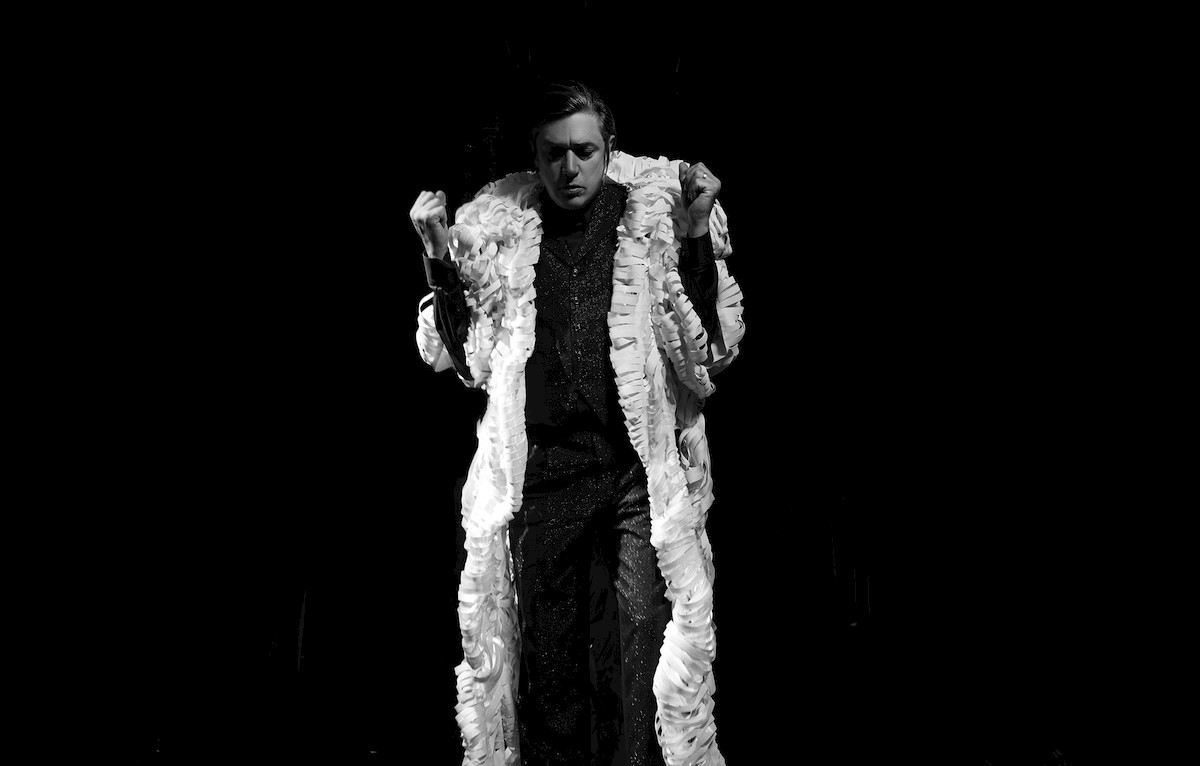

“First time since 1983 that we have a shopping cart onstage,” said Blixa proudly. He was referring to the shopping cart to his right. Before our eyes, the wheeled commercial utensil of convenience had mutated into a percussive instrument of a mechanical sturm und drang. The squeaking wheels had never tasted oil, their noise adding to the symphony. “That one has been in Utrecht twice before,” continued Blixa. The crowd cheered for the old cart making its grand return to the stage, an aged hero of mythology back from war.

The band members were barefoot, stamping with the beat. The rhythm was ancient, it was pure. The noise of soles on the wooden stage was picked up by the microphones pointed at the band members. Shadows were cast onto the white fabric backdrop, in deep blues, in fluorescent whites, in hellish crimson. The instruments, however, were not of an ancient age. The instruments were made of metal, metal on metal, scrap metal, bent out of shape, torn sheets, an empty vessel fit for an automobile factory, a dangling spring, coiled, rising like a gyre that, when hit with a pipe, resonated to the nosebleeds in reverberations and thundersprings. Alexander Hacke, the drummer (Hacke by name, hacker by nature), was battering away at the sheet metal, which was dented from years of abuse by lead pipes. Cymbals were large iron cogs cut off from their machine. Metal bars were spun on other metal bars and slammed to a stop.

Blixa pendulously altered his vocals, singing like a cabaret performer and then screeching like a chasing bird of prey, floating above the audience, looking for any slight movement in the desert sands. In fact, Blixa later came onto the stage in a buffeted collar made of black feathers. Hacke then scraped a pneumatic drill on a metal plank. Blixa dropped shrapnel onto the ground, letting it slip slowly through his fingers, cascading down and clinking on the ground in a silver waterfall.

All in All

The band released a new album in 2020 called Alles in Allem. It is a departure from the old chaos of petroleum-soaked stages going up in flames and their first album Kollaps. On stage, Blixa called the new work “a dialogue between the young and the old Blixa or should I say the old and the new Blixa.” I couldn’t understand the words of most of the songs, but sensed the band grasping to the old tradition, carrying forth the shrapnel, while viciously still banging on the anvil and forging the new, the something entirely different.

Einstürzende Neubauten finished with an old song, ‘Redukt’, off the 2000 album ‘Silence is Sexy’. Blixa talks into the microphone, the microphone practically in his throat, over a continuous clanking:

Meine Hände / Meine Arme / Meine Beine / Mein Körper / Mein Kopf - und ich

Das unveränderliche, unzerstörbare Selbst – Ich

[My hands / My arms / My legs / My body / My head - and me / The unchanging, indestructible self – I]

The clanking keeps going like a metal metronome, a guitar groans, more clanking, the words describe the anatomical construction of man and the machine, nature and the unnatural, rivers flowing, swollen deltas, endless searching for noise, in cosmic seas and whispered winds. In escalation, Blixa screams “Redukt, Redukt, Redukt!” during the chorus as the noise heightens to a gorgeous torture of metal. Redukt, or reduct, means to diminish something, to shrink its size to nothing. At the end, Blixa whispered one final Redukt into the microphone and that was the end, the complete reduction, the conclusion of the show.

I left the venue and got the train with open ears, listening attentively to the bleeping doors, the grunts of drunkards, and to the chugging of the train on the tracks underneath, noise-sounds of the symphony of everyday life.

Old foundations, endless renovation

Iggy Pop and The Stooges and Blixa Bargeld and Einstürzende Neubauten idealised, and still idealise, the infinite variety of Russolian noise-sounds, where the primal meets the machine age. It is an absolute acceptance of the world around us and noticing that all things, everyday objects, can become music.

I thought of old rockers who often say, ‘Yes, but you should have seen Iggy in 1973 when he would disappear in the crowd and come out fighting, writhing like an eel, spattered in blood’ or ‘Don’t talk to me if you didn’t see Einstürzende Neubauten set fire to the stage in London in 1986.’ Sure, they must have been memorable experiences. However, I also believe that seeing these rockstars that have made it through the gauntlet of an unhinged, hyperactive, often dangerous life, to arrive now, still making music, great music, still challenging listeners, still making young people mosh in awe, making the elders nostalgic. I want to see the wrinkles. I want to see the scars that have healed.

When offstage in downtime, Blixa does cookery classes on Zoom. In an interview, he told a Guardian journalist to always put the peppercorns in the pasta water for a cacio e pepe, it gives the flavour greater depth, like steeping tea. This could be considered a futurist technique, however, cacio e pepe is the epitome of the Marinettian stodge of pastasciutta. I say stodge from experience, I lived in Italy for a period, and after cooking a cacio pepe I immediately fell into a deep post-prandial slumber. I awoke in the early evening, a mind warped from an over-extended cheese-induced nap, to meet a friend. I told him what happened, and he said to me, of course, a bowl of cacio pepe is the all-natural Italian sleeping pill.

Iggy Pop has a pet parakeet called Biggy Pop who he sits with, plays music to as the fine-feathered bird stamps its talons and nods its beak along. Even the disciples of noise take it easy once in a while. Russolo wrote in his manifesto:

We will delight in distinguishing the eddying of water, the air or gas in metal pipes, the muttering of motors that breathe and pulse with an indisputable animality, the throbbing of valves, the bustle of pistons, the shrieks of mechanical saws, the starting trams on the tracks, the cracking of whips, the flapping of awnings and flags. We will amuse ourselves by orchestrating together in our imagination the din of rolling shop shutters, the varied hubbub of train stations, iron works, thread mills, printing presses, electrical plants, and subways.

I found inspiration in those two nights of noise at the Tivoli Utrecht and experienced joy in the fact that these maniacal rockstars take time off to cook pasta and enjoy the company of parakeets. Such activities add their own noise sound to the Russolian symphony. In response, I wrote a poem, or a manifesto of sorts, inspired by both concerts, by Iggy and Blixa and their subsequent descent, or ascent, into new waves of noise.

Pot and pan, fine beak, smooth plumage

The grinding of the pepper mill

The bubbling of the boiling water

The grating of the nub of the triangular cheese

The removal of the tagliatelle from the blue plastic packet

The water dripping from the gleaming colander.

The chirping of the noble parakeet

The combing of its elegant feathers

The harmonizing whistles between bird and man

The talons scratching on the leather armrest

The endless repetition of a high-pitched voice

And the old, still howling like vultures, still barking like dogs, still stomping bare feet, still revving the drill, still testing the foundations.

The indestructible, the malleable, the ever-clanging, ever-changing cogs of genius.

Until rubble, redukt, redukt, redukt [whispered].

(1) The original Italian is quoted in Guido Botteri and Vito Levi, Il Politeama Rossetti 1878-1978: un secolo di vita triestina nelle cronache del teatro (Trieste: Editoriale Librara, 1978), p. 215: "Dolci memorie frappés, Frutta dell'Avenire, Marmellata di gloriosi defunti, Arrosto di mummia con fegatini di professori, Insalata archeologica, Spezzatino di passato conpiselli esplosivi in salsa stor ica, Pesce del Mar Mor, no di passato conpiselli esplosivi in salsa stor ica, Pesce del Mar Morto, Grumi di sangue in brodo, Antipasto di demolizioni, Vermouth."