essay

Escape From the Internet

Eleni Maragkou

Eleni Maragkou is a Greek writer, editor, and researcher, thinking often and writing about our relationship to the media that shape our everyday lives. Sometimes she lectures about this topic too. She holds a Research MA in new media and digital cultures from the University of Amsterdam.

poetry

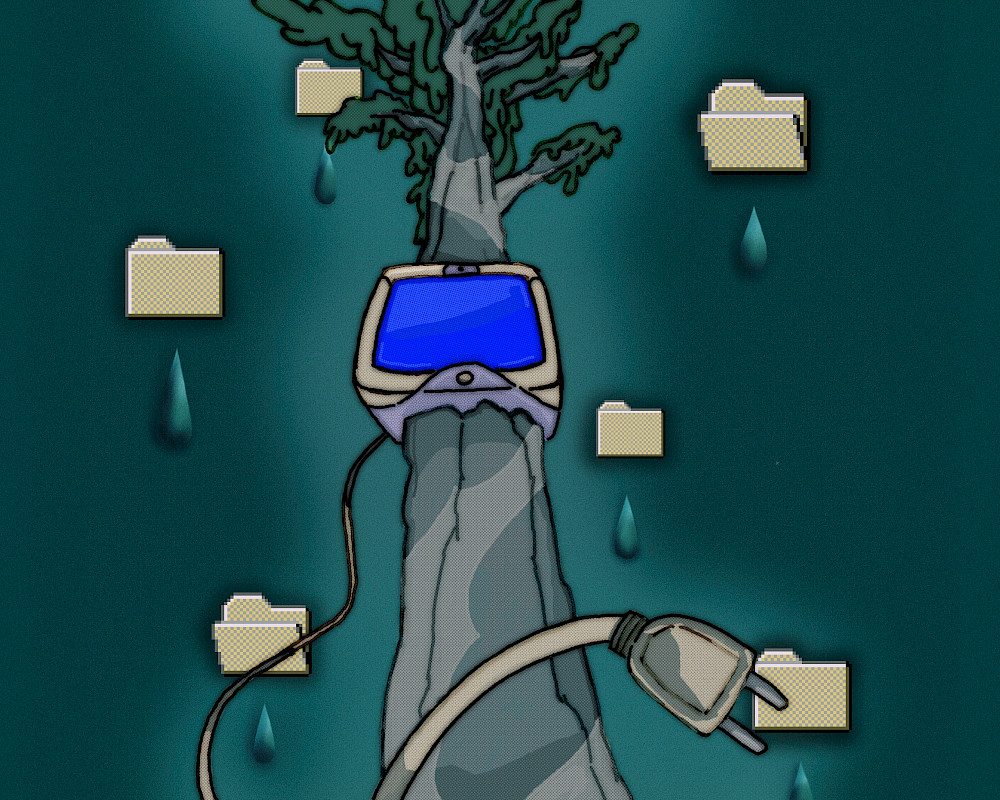

The horizon shifts as I do

Did you know that sequoia trees can grow taller than data centres can?

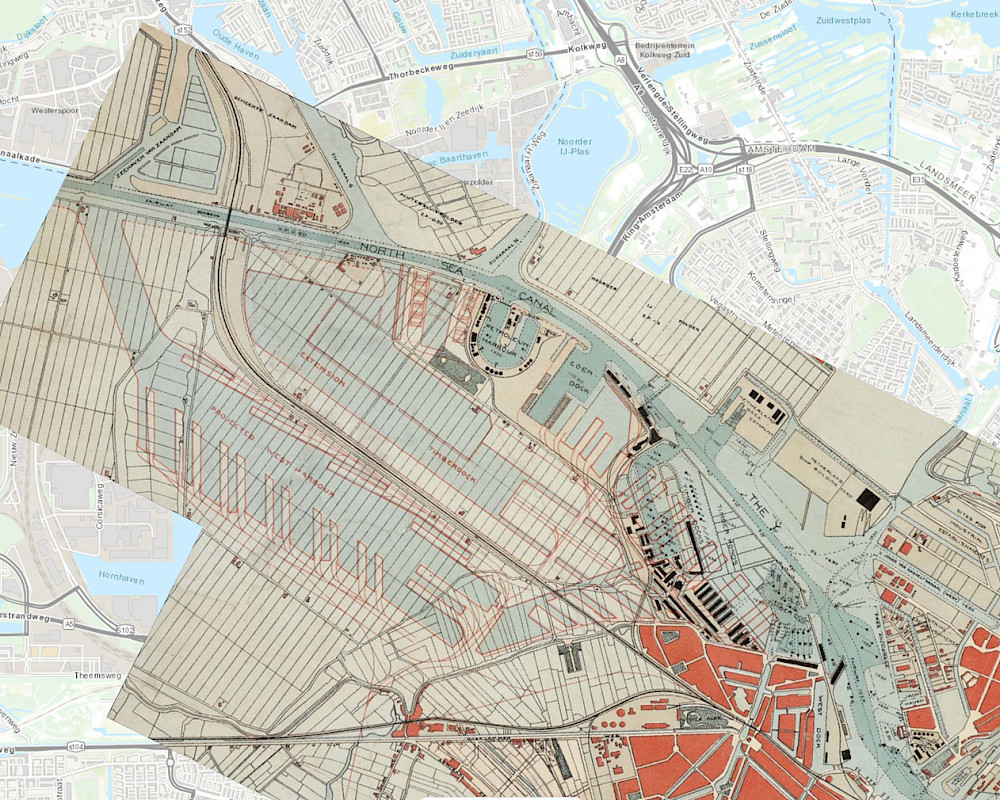

In the outskirts of Amsterdam, there are many of the latter, corrupting the horizon.

Milo Sharafeddine

Milo is a Lebanese visual artist and writer based in The Hague. Their work is often inspired by the instability of personhood, place and its social meaning, ghosts and haunted symbolism, and technology—specifically digital imagery and recording, internet-age media, and their alternative histories.

essay

Productively Unproductive

Arne Willée rescues idleness from its morally dubious past and presents it as a needed, critical resource.

video

Air

Nonlinearity is not just a collision of times, but an indifference to time

essay

Ghosthood and the Uncomfortable Familiarity of Haunting

now you tell me I remind you of a friend, but one that you can't seem to name

poetry

The horizon shifts as I do

Did you know that sequoia trees can grow taller than data centres can?

In the outskirts of Amsterdam, there are many of the latter, corrupting the horizon.

24

min read

The internet does not exist. Maybe it did exist only a short time ago, but now it only remains as a blur, a cloud, a friend, a deadline, a redirect, or a 404.

—From the introduction to “The Internet Does Not Exist”, edited by Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle.

A Massive, Expanding Surveillance State With Unlimited Power And No Accountability Will Secure Our Freedom by Hans Christian Andersen.

—twitter.com/pourmecoffee

Dear reader,

I hope that email never found you, well or otherwise. I hope that, while you read this, you will not think about your email. I ask that you exit that spreadsheet. Turn off your notifications. And although you are reading this on the web browser of your laptop (or, most likely, of your phone), I invite you to forget the internet you know, and to try and remember (or imagine) a different one, one that was and one that could be.

1993: Part One

In the beginning, there was cyberspace.

In the 1990s, this was the site of speculative reimaginings of life and personhood; or, in the words of anthropologist Michael M. J. Fischer, “a conceptual space of connectivity, information, assorted desires for escaping or enhancing the body or material world, new paralogical language games for creating selves and socialities” [1]. These were loci of worlding; or, borrowing from Donna Haraway’s claim about speculative fiction, spaces for “the patterning of possible worlds and possible times, material-semiotic worlds, gone, here, and yet to come” [2]. There, cyborgian selves are fashioned out of avatars, transcending the limitations of the physical body.

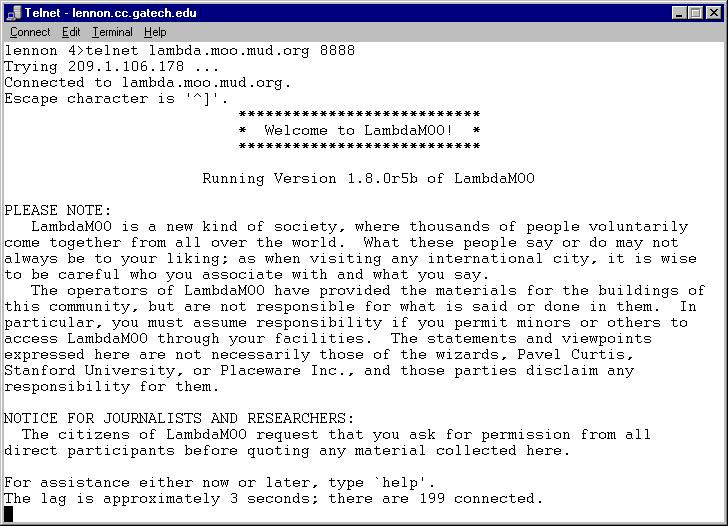

Invoked through pure creativity and imagination, these spaces were mostly textual. We can trace them back to the early days of computing in the 1970s, when text-based role-playing games allowed players to create and explore shared fantasy worlds. Those eventually moved to forums, which became known as MUDs (multi-user dungeons, also multi-user dimensions or multi-user domains), and their popularity was amplified with the advent of personal computers.

Within this realm, network accessible, multi-user, programmable, interactive systems are called MOOs—MUDs, object-oriented. In MOOs, the virtual world is structured around objects, each possessing distinct properties and behaviours. A MOO allows users (or players) to interact with each other through virtual avatars, which could range from people to animals, and is text-based, meaning there are no graphics or visuals accompanying these characters and their interactions. This is important to remember.

The oldest MOO today is LambdaMOO, and it is the site of a strange event in 1993, during which an evil clown named Mr. Bungles entered LambdaMOO and sowed chaos. Using a “voodoo doll” (a device which allows users to control the actions of another user), Mr. Bungles forced multiple of the LambdaMOO denizens into sexual acts that grew increasingly crude and violent. All of that took place over text on a screen.

When other users realised what was going on, they attempted to stop Mr. Bungles, but that proved difficult. In the end, Mr. Bungles was banished, and the event was dubbed “a rape in cyberspace” by journalist Julian Dibbell, who published an article about it in The Village Voice that same year.

The piece opens as follows:

They say he raped them that night. They say he did it with a cunning little doll, fashioned in their image and imbued with the power to make them do whatever he desired. They say that by manipulating the doll he forced them to have sex with him, and with each other, and to do horrible, brutal things to their own bodies. And though I wasn’t there that night, I think I can assure you that what they say is true, because it all happened right in the living room—right there amid the well-stocked bookcases and the sofas and the fireplace—of a house I came later to think of as my second home.

I am not interested in rehashing arguments about the porousness between the online and the offline or the applicability of terms like “rape” in this virtual context. Plus, by this point, I think, most of us are used to a certain degree of online depravity that renders Mr. Bungle’s offences almost banal (in and of itself, a disturbing sign of our times). Rather, it was Dibbel’s description of the MOO as his “second home”, as well as his evocative account of its furnishings and all of the events which unfolded there that surprised me.

Dibbel’s reflections on his LambdaMoo experiences culminated in a book, titled My Tiny Life. Dibbel describes this world as a “nascent society stirred and shaken by class conflict, mob justice, rumours of conspiracy, dreams of democracy. A circle of friends bound by disembodied affection, gossip, sexual intrigue, and political passions. An intricate, chaotic geography conjured from the imaginations of thousands of people" [3].

No doubt the principal ideas and playful worldings of MUDs and MOOs still live on. But the idea of the internet as a virtual space of endless possibility, in which one could live a “tiny life” seems rather antiquated now [4]. We can trace fragments of that earlier web at the periphery of the platform economy, in the carnivalesque hellscapes of “chan culture” [5]. There, in anonymous image boards and forums operating under the guise of free, unfettered speech, “individual identity is effaced by the totemic deployment of memes” [6]; belonging to the in-group is articulated through vernacular fluency rather than self-presentation, and no social capital can be accrued, for participants view themselves as a faceless mass.

the idea of the internet as a virtual space of endless possibility, in which one could live a “tiny life” seems rather antiquated now

This way of existing and interacting online is conducive to dissimulative identity play: one’s digital actions can be untethered from their offline life, personality, and relationships, which leaves a lot of room for transgressive or extreme behaviours. This is exacerbated by the perception of cyberspace as a realm separate from reality; there’s the online world and the real world, and that (incorrectly) implies that there is something “not real” about the former.

Of course, how can one go on the internet, if the internet is all around us? “Information,” writes McKenzie Wark [7], “is now such a pervasive organising force that it has seeped into our worldview.” Events like the “rape in cyberspace” already give us an inkling that the “real” world bleeds into the virtual, whether we like it or not, but now we see almost the inverse: the colonisation of our minds, our bodies, our feelings, of life itself by data. A while ago, I wrote a poem for this very platform, in which I reflected on the alienation I feel from my own data; my data is mined, but it doesn’t feel quite mine.

The internet used to be a place

Digital entities are elusive; “[w]hile we can manipulate [them], we cannot immediately grasp them like other material objects” [8], writes Marianne van den Boomen. Yet the language that we use to speak about it seeks to make it tangible by connecting it to our material reality or legible concepts. Windows, mirrors, icons, pages, links. Home, interface, platform. Friends, followers, karma. Heuristics that “construct fantasmatic compatibilities between the human and a realm of choices that is fundamentally unlivable” [9]. In the book Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that metaphors “can have the power to define reality”. The question of who gets to impose those metaphors has a lot to do with power.

Material metaphors (like those of the window or the mirror) craft an appearance of transparency and immediacy that is by no means natural, but rather obscures the deliberate decision-making, mediation processes, and physical infrastructures that underpin the internet.

Not long ago, in December of 2023, a meme made the rounds on the platform formerly known as Twitter, depicting what essentially was a shrine to the family computer. It is captioned: “There was a time when we respected the computer.” If you are of a certain age, you can likely recall the era of negotiating a sluggish (by today’s standards) modem connection through the phone line, a connection which wasn’t to be taken for granted.

I began to think more and more about the computer as the door that led us onto the internet: an obvious, yet practically archaic metaphor in our present moment. As another user writes: “the internet was a single, solitary, unmoving place instead of a terror that extends to everywhere. you went to this specific spot to go to the internet. when you left the spot, you left the internet. it was a place” [11].

What’s more, the internet used to be a place in which I longed to spend time. Now, I am enveloped by it, suffocated—a terror that extends to everywhere. At all times, from the moment when I open my eyes in the morning to the instant the glow of my phone screen dies, deep in the night.

A day in this life: small screen, medium screen, sometimes bigger screen, and back to small screen. The cyborgian self has moved from mere text to a machine-human hybrid, with the smartphone as an additional limb, an extension of the self with all its trappings. Mainly the expectation of ceaseless availability: Slack messages at 10:30 pm; unopened notifications hanging ominously like a sword of Damocles; work and play, leisure and life, all wrapped up with a bow. The only respite, for the time being, can be found in sleep.

Sleep, as non-productive time, is the enemy of capitalism, until we figure out a way to monetise our dreams. Time spent non-productively cannot be turned into surplus value, which means that it is in the interest of capitalism to incorporate every sphere of life. In his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Jonathan Crary describes the ruinous consequences of “a time without time, a time extracted from any material or identifiable demarcations, a time without sequence or recurrence” [12]. According to Crary, the “relentless incursion” of this non-time is responsible for the erosion and atrophy of community and sociality.

How long will it be before our dreams are colonised too?

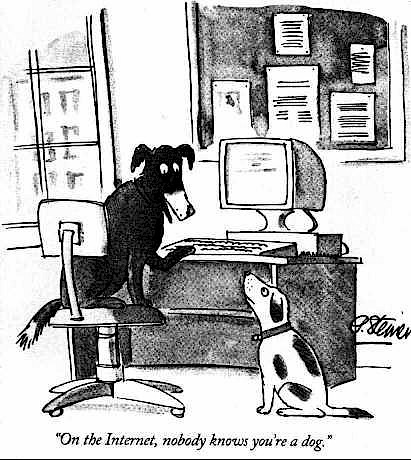

1993: Part Two

It is 1993, again. The New Yorker has just published an illustration by Peter Steiner that has since been embedded in our cultural imaginaries of the web. In it, there are two dogs; one is sitting in front of a computer, paw on the keyboard. “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” says one dog to the other. At the time, Internet protocols didn’t require verification of one’s identity. Since then, things have changed.

Anonymity has become a scourge, even within progressive circles. It is often the harbinger and enabler of toxicity, cruelty, and bigotry, they say. So now we are stuck with an internet that reveals more than it conceals, at least about us. Fragments of our identities exist scattered across forums, social profiles, and comment sections, and, if necessary, they can be glued together to produce a Frankenstein’s monster narrative of our lives. Take, for example, the creator of the Tumblr page that essentially transformed 2010s celebrity culture and the politics of accountability. Helmed by a then teenager, the blog was a venture into “vengeful public shaming masquerading as social criticism”, anxiously excavating unsavoury facts about celebrities. Or, more recently: last year, “West Elm Caleb”, a designer/designated persona non grata, whose crime was ghosting several young women in Brooklyn and who was doxxed after a series of TikToks dug up his personal information, diagnosed him as a lovebombing narcissist, and urged his employers to fire him.

The 2024 version of that New Yorker illustration would be more along the lines of: “Remember when on the internet no one knew you were a dog?” From mainstream social media platforms, most of whom now demand us to not only to tether our digital avatars to our offline identity and activities to the self-disclosure imperative, the private self has become a brand, which needs to be cultivated and curated for a (real or imagined) audience; the storytime-industrial complex has rendered life’s minutiae up for public consumption. Wireless technologies allow us to document, archive, and disseminate everything, “annihilat[ing] the singularity of place and event” [13] in the process. Strangers’ conversations and phone screens can be captured at any moment and displayed for the temporary entertainment and scrutiny of potentially millions.

Fragments of our identities exist scattered across forums, social profiles, and comment sections, and, if necessary, they can be glued together to produce a Frankenstein’s monster narrative of our lives.

This current condition is characterised by what Clare Birchall calls shareveillance, an asymmetric state in which subjects are at once surveillant and surveilled. Under the guise of transparency, we are called upon to be more open by all-encompassing, borderless systems which answer to no one and from which there is no reprieve.

The epidemic of digital (un)wellness

Jumpscare: My daily screen time notification appears. It’s up 8% from last week. I don’t dare dwell too much on the number of hours I have dedicated to looking at the small rectangle in my hand—a small lifetime. That of a young adult. (Or so a website that calculates your lifetime in screen time told me.)

Every once in a while, one of my mutuals publicly declares their decision to abstain from online frivolity—any type of “superfluous” online activity in the vein of posting an Instagram story. Few succeed. Inevitably, most of them timidly crawl back, hoping we have all since forgotten their lofty promise. No judgement here. Like most of my friends and acquaintances, I work in the extremely broad and precarious cultural field, which sadly often means that Instagram replaces the functions of LinkedIn and offline networking, making it difficult to abstain. Plus, these apps famously have addictive features baked into their design.

The entwinement of labour and leisure that is experienced when the digital leaks into every aspect of daily life tends to create a rather binary view of the time we spend online: productive or lazy. Meanwhile, the blackboxed algorithms that hook users to apps like TikTok are rightfully viewed with suspicion. The (widely critiqued and discredited, yet enduring) hypodermic needle theory of the 20th century, which posits that media consumers are easily manipulable, passive receptors of content, has been reconfigured for the digital age. We speak about non-productive online activity using the language of addiction or entirely banish it to the realm of the “unreal”. In fact, it is precisely this slippery quality that makes this experience so lonely, so difficult to talk about. In the words of my editor, Maia Kenney, “we’re fucked because we are collectively beholden to sth that we have agreed does not exist in the same way that a cigarette does. And the ‘not real’ thing is one that can ONLY be experienced individually”. Trapped by the motion of swiping on a screen into a cycle of compulsion, repetition, and shame, we now doomscroll. To heal, we need a digital detox or a media fast.

Entire apps are now designed to restrict screen time. Of course, these are inherently suspicious: how can the “cure” for an imagined ailment come from within the thing that it claims to cure? (Possibly, this has something to do with the principal goal of such apps, which is to improve productivity. Screen time is bad only if you don’t meet your KPIs, silly.)

It’s almost as if we are trapped in an obsessive bond with the digital, one that can only be broken through hacks and hexes, digital snake oils. Some research shows that “half of Gen Z” want to “take a break from their smartphones”. Such authoritative findings always give me pause, but there is anecdotal evidence to support this. In 2022, The New York Times published an article about “luddite” teens, who have turned their backs on iPhones, opting instead for flip phones—or even better, no phones at all [14].

We speak about non-productive online activity using the language of addiction or entirely banish it to the realm of the “unreal”.

In English folklore, Ned Ludd was a textile worker who, in a “fit of passion” over the introduction of new weaving machinery, supposedly destroyed two stocking frames, ultimately inspiring the Luddite movement against industrialisation. Though the word “Luddite” is now used to mock those who obstinately mistrust resist technology, there are some contemporary reconsiderations of the movement as worker-led resistance to automation, an issue all the more timely during the age of AI and Endless Screen Time [15].

In the Times article, one teenager recounts her compulsive relationship with her smartphone. “I became completely consumed,” she said. “So I put my phone in a box.” When I Google “phone lock box”, dozens of different products appear, most of them sold on Amazon and other dubious online retailers. The irony of a platform like Amazon (the second largest private employer in the world, after Walmart) selling me a tool that is supposed to help me limit my online activities is not lost. I can use my phone to purchase this tool, even.

To be honest, I find moralising about the internet to be trite, tired, boring. I am not like my father, who blames all my psychological ills on my screen time. But there is something I am noticing about this almost compulsive, chore-like relationship I have with it. Maybe it’s a relationship hump. After all, we’ve been together for almost fifteen years. The novelty has worn off. In fact, new media has become old. The “new” has always been somewhat of a misnomer. All media have been “new” at some point; all media evolve into a middle age where they begin to be seen as outdated and irrelevant. Some media die. And some media live long enough to… you get my point.

The internet is nowhere and everywhere, spilling onto the fabric of everyday life. Our cities are now smart. There are apps which quantify data about our bodies and use that to infer patterns about our behaviour. And our home appliances are plugged to the cloud. Though it is tempting to apply a Latourian reading of the situation that considers the agency of non-human, inanimate objects, I don’t need to be able to tweet from my fridge. I just need it to preserve my perishables. “We’re empowered to report failed trash pick-ups or rank our favorite hospitals,” as Shannon Mattern wrote already ten years ago, “but not entitled to know what happens to our personal data each time we pass through a toll booth, or how the doctor we rarely see knows our cholesterol is up” [17]

The internet, once an alternate world into which we once used to escape, has turned into the all encompassing quagmire we now seek to escape from.

Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Enshittocene: On the internet, no one knows you’re a bot

As if we’ve run out of neologisms to describe these times (derogatory)—in 2022, author Cory Doctorow coined the evocative term “enshittification” in an essay about web platforms’ deteriorating services:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. [18]

Enshittification (selected as the American Dialect Society’s 2023 Word of the Year!) describes the colonisation of the internet by platforms; a phenomenon so vast and all-encompassing, according to Doctorow, that in 2024 he returned with a sequel: enshittocene. The gist is: we’ve been essentially lovebombed by platforms that for years were eager to please us, at a loss to their stakeholders, and are now revealing their rotten core. No longer incentivised to keep up the charade of good user experience, they have established a monopoly of, well, shit.

This has made the internet basically unusable, a wasteland in which search engine results are polluted by sponsored or AI-generated results and social networks spoonfeed us content we never asked to see. And as if that weren’t enough, the internet has been pronounced dead. This happened, apparently, sometime in 2016 or 2017.

At least, that is according to a conspiracy theory known as “dead internet theory”. And as all good conspiracy theories, there are some kernels of truth to be found. In a nutshell: the internet is a ghost town, populated by malicious spectres. Here I am not only referring to the vast amounts of data that persist online, even after a person’s physical death. There is a fringe theory positing that the internet is overrun with bots, deepfakes, and AI-generated sludge, displacing authentic content made by real human beings.

“Dead internet theory” likely emerged in the cesspool of the true internet: 4chan. It was popularised in a 2021 Agora Road's Macintosh Cafe thread titled “Dead Internet Theory: Most Of The Internet Is Fake”. This thread alleges that the internet is now “empty and devoid of people” and “entirely sterile”, an accusation which at first seems absurd: if anything, the internet is crawling with content. Yet, a great deal of this content feels like a façade, or worse, a psyop. So, some cataclysmic shift must have occurred in 2016 or 2017. Hm. I wonder what significant political event that cultivated and fed on mistrust and collective paranoia transpired during that period…

In a 1964 essay titled “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”, Richard Hofstadter diagnoses a style of conspiracism that has infiltrated politics. Dead internet theory doesn’t see aliens or racial and ethnic caricatures as our invisible overlords, manipulating the strings of history, but bots. These bots are deployed by the usual suspects (the government, the deep state, corporations) to manipulate and control. According to the poster of the original thread (aptly named IlluminatiPirate): “The U.S. government is engaging in an artificial intelligence powered gaslighting of the entire world population.” Under the paranoia, however, lies a legitimate concern: an absence of agency, a lack of control, a frustration with and fear of mechanisms and structures that are beyond our scope.

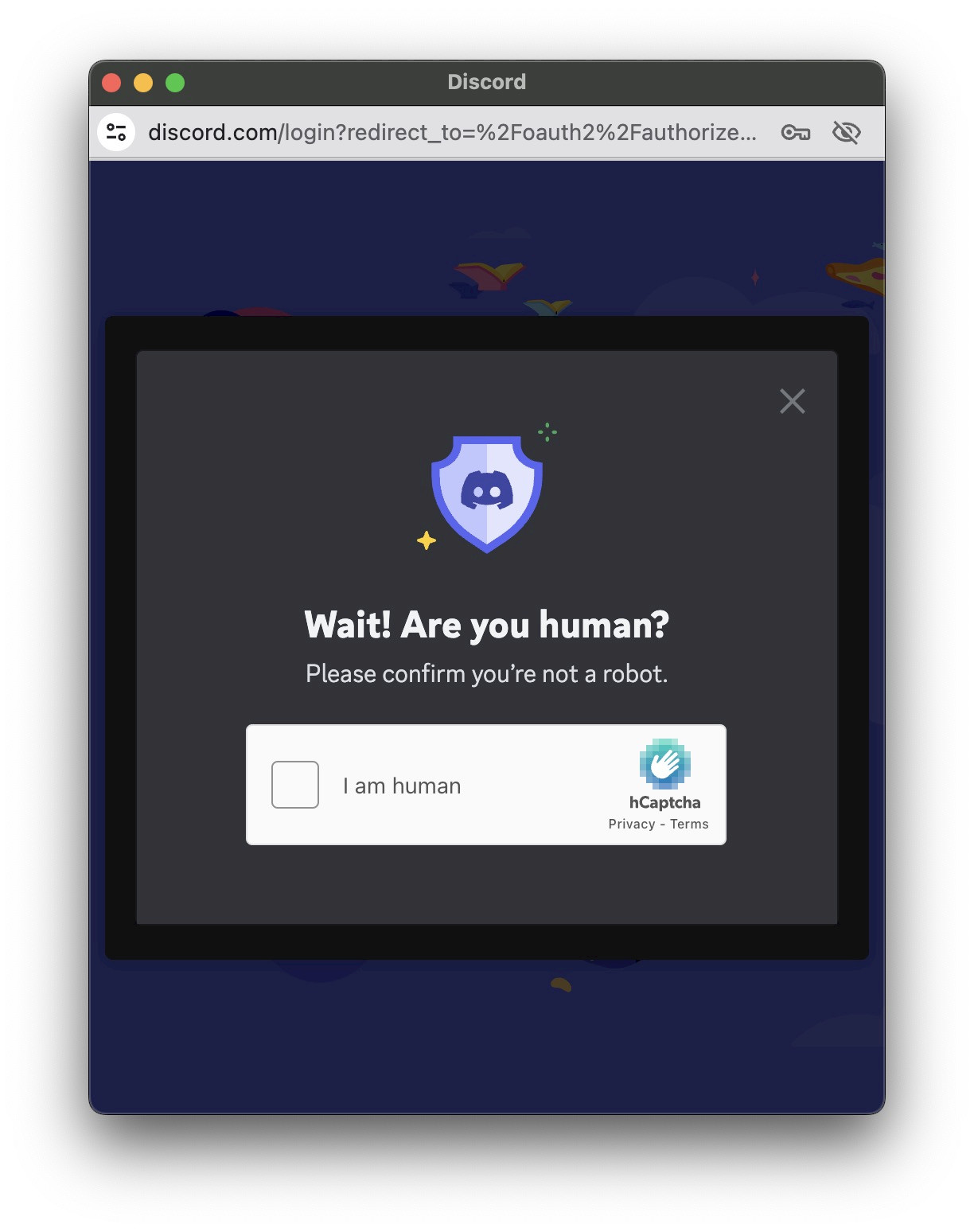

If the zeitgeist of the late 1990s consisted of the “y2k problem”, we are now faced with the existential threat of “the Inversion”, a sort of reverse Turing test, in which bot content is marked as authentic, while human content is flagged as inauthentic.

Any casual interaction with the uncanny is now suspect. Take for example the paranoia unfurling in and around the infamous video of an airplane passenger yelling “That motherfucker back there is not real!” After having been inundated with generated spectacles trying to pass themselves off as reality, we grow inherently distrustful of anything that looks a little “off”—offline and on.

A venture into TikTok, the platform formerly known as Twitter, or, for our elders, Facebook, reveals a theatre of the grotesque: digital cryptids, sex bots, click and stream farms, text to speech absurdity. The attention economy is a monster that demands to be fed, and its diet consists of low nutritional value slop.

If the zeitgeist of the late 1990s consisted of the “y2k problem”, we are now faced with the existential threat of “the Inversion”, a sort of reverse Turing test, in which bot content is marked as authentic, while human content is flagged as inauthentic. [20]

The dead internet theory reveals a grim and hopeless prospect, no doubt. I feel compelled to concoct an optimistic, speculative reimagining of a more-than-human internet with which I could make kin. An internet that exists somewhere beyond the sea of phishing links, ersatz babes inviting me to view their genitals through the link in their bio, aberrant Midjourney imaginaries, and bootlicking sockpuppets defending Amazon. An internet that won’t make me download an app so that I can momentarily free myself from it.

On occasion, I catch glimpses of that internet—in the playful collaborative Alternate Reality lore of Goncharov, the fictitious Martin Scorcese film concocted by Tumblr denizens; in the (endangered, but resilient) electronic libraries making the breadth of otherwise inaccessible academic knowledge available to all those who know where to look; in the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine. Perhaps the internet is no longer a place; perhaps it is an assemblage of dispersed potentialities: for collectivity, for nonhierarchy, for unabashed everyday creativity.

Endnotes

[1] Michael M. J. Fischer - Emergent Forms of Life and the Anthropological Voice, p. 261.

[2] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, p. 16.

[3] Julian Dibbell, “A Few Words About My Tiny Life, From the Man Who Wrote It”. http://www.juliandibbell.com/mytinylife/tinyspiel.html

[4] The last time I experienced what Dibbel is writing about here was as a pre-teen navigating Stardoll: a part-dress-up browser game, part-virtual community, where users could create a virtual paper doll avatar in their likeness or not, take it shopping, dress it up, and decorate its multi-story home. For millennial and zoomer kids, Stardoll truly felt like an immersive world within a world, one in which you could be leggy blonde with a closet full of designer shoes—even if, in reality, you were a scrawny, brown-haired twelve year-old with braces.

[5] Imageboards like 4chan and 8kun, websites like Something Awful, the infamous Encyclopedia Dramatica are all heavily affiliated with the more unsavoury aspects of internet culture. 4chan, in particular, is credited as the birthplace of meme culture, activist group Anonymous, and the alt-right. Yet it has also been called the “cesspool of the internet” (see: https://www.wired.com/story/4chan-happy-birthday/). The aforementioned milieus form a constellation known as the deep vernacular web, a deeply ambivalent stratum of the web, which exists slightly beyond the scope of the platform economy, in a somewhat ungoverned space of dissimulative identity play, mischief, and reactionary antagonisms. (See: Daniël de Zeeuw & Marc Tuters, “Teh Internet is Serious BusinessSubtitleOn the Deep Vernacular Web and Its Discontents”, in Cultural Politics.)

[6] Marc Tuters, “LARPing & Liberal Tears. Irony, Belief and Idiocy in the Deep Vernacular Web”, in Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right: Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US (edited by Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston), p. 40.

[7] McKenzie Wark, Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse?, p. 5.

[8] Marianne van den Boomen, Transcoding the Digital: How Metaphors Matter in Media, p. 103.

[9] Jonathan Crary, p. 100.

[10] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, p. 5.

[11] Which place? Perhaps the hills of California's Wine Country, or more famously the beloved “Bliss” Windows XP wallpaper.

[12] Jonathan Crary, Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, p. 29.

[13] Jonathan Crary, Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, p. 31.

[14 Alex Vadukul, “‘Luddite’ Teens Don’t Want Your Likes.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/15/style/teens-social-media.html

[15] See: Brian Merchant, Blood in the Machine.

[16] Alex Vadukul, “‘Luddite’ Teens Don’t Want Your Likes.”

[17] Shannon Mattern, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence”, Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/article/interfacing-urban-intelligence/?cn-reloaded=1

[18] From “Pluralistic: Tiktok's enshittification”. https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

[19] Per the website’s own description: “Agora Road's Macintosh Cafe is a Virtual Cafe where travelers from all around the net can come here to talk about nostalgia of the Y2K era, vaporwave music, and things of the past!” Fun! A Reddit user provides us with a crucial addendum: “They leave out the part where weird extremists lurk around changing the subject into right wing politics. This is mainly because they recruit members from 4chan.” Not so fun.

[20] In actuality, it looks like AI, at least for the time being, is not eliminating human workers; rather, much of fear-mongering around AI tends to obscure the spectre of human labour required to maintain it—from underpaid Kenyan workers toiling to filter toxic content from ChatGPT to the thousand Indian employees making up Amazon’s “AI-powered cashierless technology”.