essay

Thinking through the supermarket

Ilaria Obata

Ilaria Obata (she/her) is an art historian, public programmer and researcher based in-between public institutions and spaces of leisure. Currently, she can be found in the archives and the reception desk of the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam. She holds an MA in Curating Art and Cultures at the Vrije Universiteit / University of Amsterdam.

Maria Vorobjova

Maria Vorobjova is a London-based designer; artist; cyber sprite.

Her work playfully weaves together maps of ethereal (virtual;dream;club) worlds with saturated, shimmering threads.

essay

The Image of an Image is a Memory: Clash of the Imperial Gaze

Today, a walk in the museum is a walk with a camera. Is the hegemonic narrative of the exhibition questioned by the camera? Or does the camera become an accomplice to the museum?

essay

In The Door Opening of The Bedroom

'The bedroom is the locus of a becoming, spread out across multiple dimensions. Every night, as I close my bedroom door behind me, this process is set in motion, and every morning, just as it is about to become actualised, it disappears.'

fiction

Cup Run Over

smiling my best smile I asked him what sort of work he was in, my eyes moving down to the cup in his hand.

fiction

The Boys Next To Her House

"I thought about a cold beer and cigarettes in the garage. I’d kill for that."

fiction

Mademoiselle de Sade

"She cleaned him, made him pray; she ate him violently like a fat pig enjoying its last meal."

13

min read

In this exploratory essay, I open the closed space of the large-scale supermarket chain to new considerations, arguing that it can offer the consumer-turned visitor an affective space of convergence between commodified extractivism, ritualized consumption, and 'rewarding' self-actualization.

Supermarkets have always been a space of enticing wonder for myself and my friends. As you enter this non-space – where our own understanding of the linearity of time stops and a sense of urgency disappears when browsing through the aisles – you can wander there for as long as you like and people tend to leave you alone. So why is going to the supermarket such a reward for some, and for others such a taxing chore? It's a space that does not just offer us commodities in the form of baked goods, fresh produce, cheap(ish) booze under the heavy glare of artificial UV lighting, but it makes us think about our wants and desires when prompted to. Yet, the habitual routine of entering a supermarket chain is almost universal from country to city to neighbourhood - its spatial design leads the visitor/consumer to follow the same exact steps: enter the store, grab a basket, browse the aisles for different offers and commodities, check off their grocery list, place the products into their basket, and pay for their items at the cash register. I had to re-learn these steps when I moved to the Netherlands, as supermarkets aisles here are organised differently compared to spaces I’ve grown up in. Whereby, most supermarket chains do not have shelves for "Asian" or "exotic" foodstuffs— instead tins go with tins, grains with grains etc, never mind the regional "theme" of the dish for which you are shopping. But this form of categorical spatial design can offer more possibilities that simply hyper-consumption.

Supermarkets have always been a space of enticing wonder for myself and my friends. As you enter this non-space – where our own understanding of the linearity of time stops and a sense of urgency disappears when browsing through the aisles – you can wander there for as long as you like and people tend to leave you alone.

For some, the supermarket is not just a place of monotony and of consumption. It can also provide the consumer with a sense of escape from their workplace, their home, a process that detaches them from what they were previously doing; a routine to escape from their other routines. The mundaneness of grocery shopping can offer a form of comfort, knowing that one can expect the same experience as they have before, but also encounter a few surprises during their journey. This routine is accompanied by the white noise of beeping cash registers, company-owned programming, commercial radio stations, and phone conversations with friends, family or dinner guests on what to eat. If one stops to look again at the space itself we can see just how our movements are conditioned by the effects of careful selection, based on feelings of nostalgia and comfort, but ultimately of repetition.

The possibilities and the impossibilities that the supermarket as a public-private space offers to us as visitor/consumers can be seen through a lens of not just classism and gendered divisions, but through the effects that this visitor experience produces. From nostalgic remembrance to scrutiny when peering into other people’s shopping carts; from seeing sweets and snacks you would get as a reward when you were a kid, to questions of cultural memory and heritage.

Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux’s book Look at the Lights, My Love also offers us a way to understand just how much our everyday supermarket spaces are constituted within the convergence of ritual, habitual and decadent routines that we both enjoy and detest. In her telling, supermarkets are more than just retail hubs; they are microclimates. Like flashy spaces of leisure and hedonism, they’re severed from their surroundings. It’s easy to lose your bearings: temperature is regulated, shelves are rotated and refreshed, the overall ambience is carefully controlled. To go inside is “to abruptly land in the effervescence, trepidation, and sparkle of things”. This experience, thus produces one of the small pleasures we get during this lifetime: gallivanting as a flaneur within the many aisles of a large-scale supermarket chain.

Commodified extractivism

Why does it matter that supermarkets are organised in categorical aisles? What are we consuming invisibly through these ethnically branded commodities? How does the organised space of the supermarket question the ways in which we think about food and how it is displayed to us? These questions can be grappled with through the work of Indonesian artist Elia Nurvista. Nurvista's Noble Savage Series asks the viewer how we are limited by the ways in which we choose to purchase and consume the goods displayed to us within the supermarket. And ultimately how these display practices are demarcated by practices of racial branding and racial categorisation.

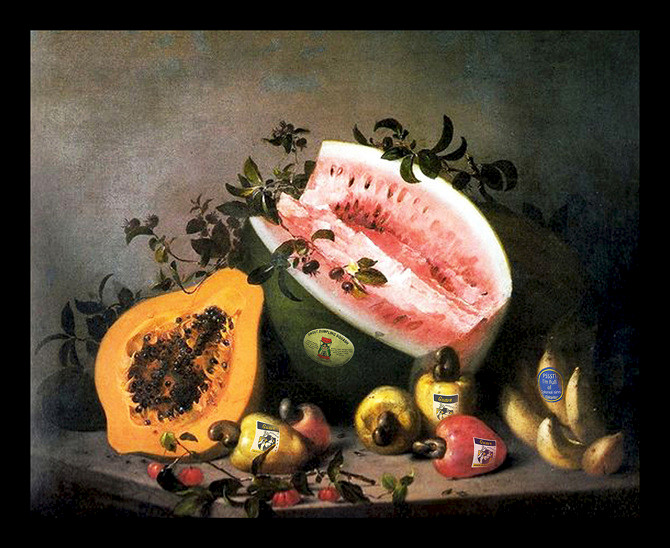

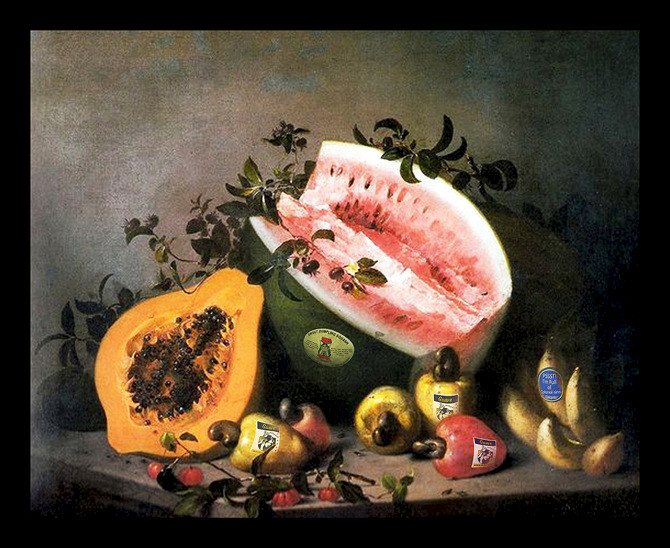

As part of this series, Nurvista turns Renaissance still-lifes – genre paintings that subtly remind us we are on the way to the grave – into humorous pictures that highlight the economy of extractive capitalism as an inherited structure of imperial power. Taking fruits and produce from a still life painting, Nurvista adds small fruit stickers, which imitate the produce stickers, referred to as PLU (price look-up) ones, that have a series of digits on them intended to provide information on the variety, price and point of origin to shippers, supermarket check-out tills etc. and they can give consumers (if they are able to decode the digits) a peek into how the product was grown.

Nurvista cleverly uses the PLU imagery and writes on the small stickers: ‘psss we’re full of colonial sins’ or ‘Latin pride’. These stickers not only remind us as (hyper)consumers that: 1) our everyday recipes have homogenized entire culinary histories, but 2) how the produce we consume, which is cleaned, sprayed, and displayed to us under UV lighting, is mutually constituted within a curatorial logic of categorising difference (Tony Bennett). This logic of differencing controls how the information we receive about these commodities, more specifically how the 'exotic' fruits and vegetables like in Caravaggio's still life paintings, influences our consumption of them. Yet, because of their normalised presence in grocery store aisles, we think that they belong here – amongst the potatoes and beetroots, and we are unable to see how far they have come from and under what conditions. The exoticised fruits and vegetables imported from climates that can actually grow this produce and harvested by indentured and oftentimes illegal labour is masked by the supermarket itself. A space that homogenizes this produce and masks its commodified extractivism. Produce that is bred for longevity to last the thousands of kilometres it has to travel to arrive to your temperature-controlled fridge.

The ritual of consumption

The way these products are displayed to us and consequently consumed by us can be analysed through Tony Bennett's exhibitionary complex, in relation to museums, universities but also department stores "which provided a context for the permanent display of power/knowledge. And for a power which manifested itself in continually displaying its ability to command, order, and control objects and bodies, living or dead". By understanding the exhibitionary complex along the aisles of display in the supermarket, we can write the supermarket into a history of display of relational power, that organizes commodities as they often are according to monolithic amalgams, purposed for ritualised consumption.

Bennett draws on the work of Michel Foucault, together with the work of Antonio Gramsci – 19th century philosopher, and politician – to argue that "this display of power in the ancièn regime had created the spectacle of the scaffold as part of a system of power which sought a renewal of its effect in the spectacle of its individual manifestations". These individual manifestations of power were presented through the likes of Great Exhibitions, and later on the department store and shopping mall. Similarly, the supermarket display can be placed within this spectacle of the scaffold, as a product of imperial power: a power of inert governance and ordering. A display of abundance.

Through the exhibitionary complex that Bennet draws upon, we can see how certain possibilities opened up in the modern-day supermarket display – to attract the consumer and to allow this experience to become routine for them by implementing a standard layout and blueprint spatial design. With fresh produce as you enter, and toiletries placed towards the check-out tills at the end. This type of design was allegedly created by Joseph Unger, who originated the concept of customers using baskets to collect groceries before checking out at a counter. The possibilities of this standardized layout are further explored through the Guillame Bijl’s recreation of the quintessential British Tesco supermarket chain, renamed Your Supermarket, placing the visitor directly within a copy of the national British supermarket chain.

Your Supermarket extracts the original purpose of a supermarket, and instead displays it as a meaningless machine, an object of spectacle. This extraction of utility, of purpose, further accentuates a visual aestheticizing of everyday consumer habits, that are shaped by the flashy aisles organised along specific categories: British fresh produce aisle, British crisps aisles, and the British Cadbury chocolate aisle.

Bijl's installation destabilises the visitor and alerts them to the ethnographic process of consumption. It is an estrangement from the everyday that allows the visitor to see the regional and national supermarket chain that Your Supermarket imitates for what it is: a practice of ethnography. Your Supermarket is writing and a documenting of what Bijl along with the rest of visitors trapped within cycles of consumption have seen, and what we have been participant to. If the exhibitionary complex is also a place of didactic knowledge production where one is disciplined through the act of seeing and being seen, then the visitor in Your Supermarket does not receive information about its commodities through the process of purchasing, but by being invited to look again at the structuring logic of a national supermarket chain. The relationality that is created within the supermarket chain space goes beyond the act of purchasing, and as argued by Daniel Miller in his publication the Theory of Shopping, going to the grocery store is not simply an ‘’act of individualism or materialism’’, but a ritual sacrifice that occurs in three acts:

Step 1: as Miller suggests is a vision of excess, which closely ties to Bennett's reading of the spectacle of the scaffold. This is exactly what the supermarket's design offers in this first ritual step – it shows the consumer what it has to offer through its artificially packaged abundance, and we participate in the careful selection of these products.

Step 2: Smoke ascends to the divinity, seen as a central act in the sacrificial ritual. It is seen as a separating act between the sacrifice itself and the offering to the divine form. Yet, Miller argues that for shopping to be comparable to sacrifice it must go through the same of kind splitting process and in his argument, this can be through the element of thrift, or bargain hunting. Seeing as thrifting separates the act of shopping from the act of excess consumption and expenditure. This second step in the ritual can allow for this negation.

Step 3: the sacrificial meal is argued by Miller as the last step that is taken in the context of a collective act of consumption and feeding – which he places in a relational dynamic between nuclear families with the last step being that of eating together, after the thrift and after the abundance of choice that grocery shopping offers. As he mentions that "feeing the family then stands for the modern act of consumption in an analogous relationship to feeding the community in ancient sacrifice". Yet, this relationality doesn’t only exist in the context of family, it points towards the closing of the sacrifice, from a transcendent realm back into the profane – of social order, distribution and consumption.

Shopping as self-actualizing

In effect, this ritual sacrifice can only be rendered through the relationship between the shopper and for whomever they are shopping. It moves away from a much more individual process of self-actualization that shopping can produce. Where one also shops for the purpose of rewarding themselves, and not anyone else. This process of (individual) self-actualization can be seen through Bruno Zhu’s curatorial practice A Maior. Albeit not situated within a supermarket space, A Maior takes name of a clothing and home goods store located in the outskirts of Viseu, Portugal. As mentioned by Zhu, ‘’Since 2016, A Maior - is an eponymous exhibition program that has taken place within the shopping environment. A Maior is managed by the staff, the artist Bruno Zhu and his family’’.

Unlike Miller’s shopping-as-sacrifice, A Maior considers how the act of shopping can provide a much more individualistic and obsessive concern to shape and situate oneself through things purchased, worn, and consumed. It is more akin to Annie Ernaux’s analysis of the supermarket space itself, and what it has to offer us as an escape through becoming. In fact, Zhu - in an interview with Domeniek Ruyters - argues that this curatorial project inside his family store ‘’can be a political project born out of a consumerist language — if one consumes, therefore one becomes’’. Zhu goes on to explain that this program set up inside this private-public space asks the visitor/consumer what it would be like to "be confronted with an artwork whilst looking for a pair of socks or a fridge magnet". Zhu describes this curatorial practice as a practice of "learning-by-placing’: allowing uncanny placements/displacements, absurdist associations and blunt encounters.’’. The importance of placement and displacement within the ritualised habit of consumption is thus central to this practice. And more broadly, the understanding of how our consumption habits shape our sense of self. This form of becoming is further accentuated by the reward that one grants themselves during this trip to the store or supermarket.

This form of becoming is further accentuated by the reward that one grants themselves during this trip to the store or supermarket.

So, what does this mean for us? We cannot do without supermarkets as our lives and habitual routines are intrinsically tied to them. Our habitual routines inside this space commodify and hide extractivist food structures. These categories of ordered abundance allow us to repeat the same sacrificial rituals we are used to. Yet, they also offer us a form of self-actualization. Thus, the supermarket’s categorical spatial design can offer more possibilities than just hyper-consumption, seeing as the supermarket's ‘’innocence’’ as a space of thoughtless wandering, or planned essential activity, has never truly been considered a space for investigative curatorial discourse and mediation between commodified extractivism, ritualized consumption, and 'rewarding' self-actualization.

Footnotes

1 Annie Ernaux, Look at the Lights, My Love (The Margellos World Republic of Letters), Yale University Press (April 4, 2023).

2 A term coined by philosopher and scholar Walter Benjamin, as the essential figure of the modern urban spectator.

3 Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 'Exhibitionary Complexes', in: Ivan Karp et al. (ed.), Museum Frictions, Durham (Duke University Press) 2006, pp. 35-45 (p. 35).

4 Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics, London (Routledge) 1995, p. 65.

5 Linda Lynwander (11 July 1993). "Recollections of First Supermarket". The New York Times. p. 9.

6 Daniel Miller, A Theory of Shopping, Cambridge (Polity Press) 1998.

7 Daniel Miller, Theory of Shopping, p. 107.

8 Daniel Miller, Theory of Shopping, p. 107.

9 A Maior: Retail Vérité – San Serriffe (san-serriffe.com)