essay

Some word, some gesture, some sound: A Ghost Story

Asa Horvitz

GHOST: Credits

Credits for Asa Horvitz' GHOST

12

min read

January 15, 2017.

I am sleeping in the studio outside my father’s house. Inside the house he is dying.

I am dreaming. In my dream my father lies stretched out in front of me, his head to my right. I am holding him. This is the moment of his death. In my dream I say to him, “when you die, go out of your body through the top of your head.”

500 AD.

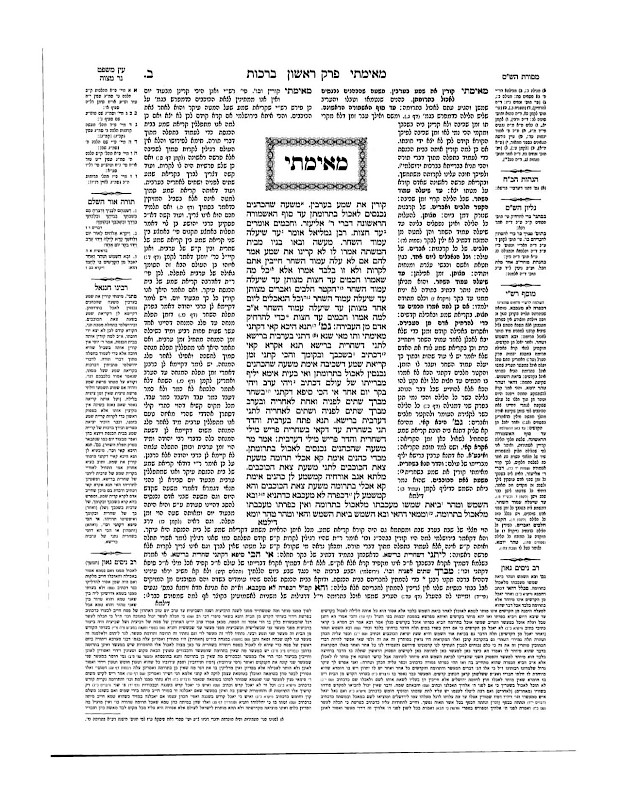

The Rabbis in the Talmud can’t agree if we living can contact the dead or not. One says yes, but only in dreams. Another says it’s impossible, the dead are gone, only their bones and hair remain. Another says it is easy to speak to the dead, but it is forbidden. Another says yes, it is allowed, but only in cases of absolute necessity, for example to settle a legal dispute. Another says the dead are right here – there are 5000 dead on your right shoulder, and 10,000 dead on your left shoulder, but to see this would just be too overwhelming.

1940.

Walter Benjamin writes: “the Rabbis forbid the Jews from consulting oracles to look into the future. It gives the future too much power and magic. Instead the Torah instructs the Jews in remembrance, in mourning, in turning towards the past, towards the dead. It is this which allows each present moment to become a gate through which the messiah might enter.”

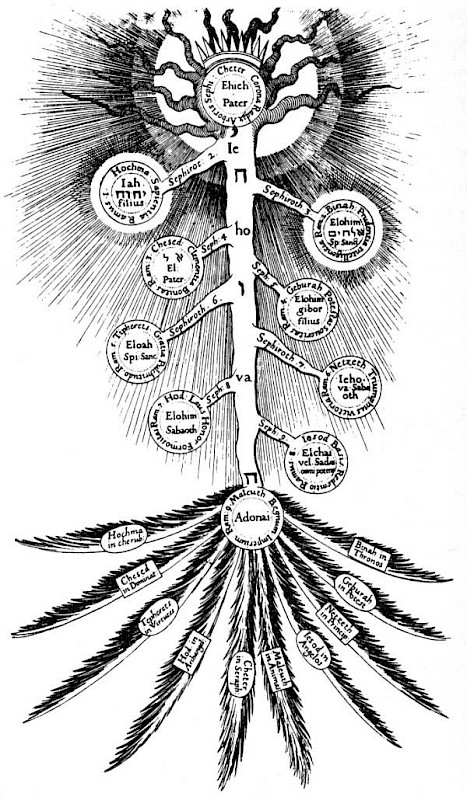

And how do the Rabbis turn towards the past? They use language. Layers of stories, commentary, argument, growing over centuries. Each letter in the Talmud has a corresponding number that can be transformed and interpreted mathematically. The letters together form words that pass through the throat and mouth and become sound. The Rabbis remind us: "whisper these words, sing them, let them into your body, and they might change you.”

March 30 2005.

My father’s youngest brother Philip dies on a flight from New York to California. He is on his way to my father’s wedding. My father collapses. He cries every day for six months. He cries at baseball games, in the grocery store, onstage with his guitar in his hands, at Thanksgiving dinner, and in his red Honda Civic picking me up from high school. I am sixteen and it scares me. I think it can’t really all be about one death, this constant weeping. My friends and I make fun of him behind his back.

One day I ask him if his crying is really all about Phil. He looks at me like I am the stupidest person on earth, like I will never in a thousand years understand anything. He says, “Asa, it’s just life”.

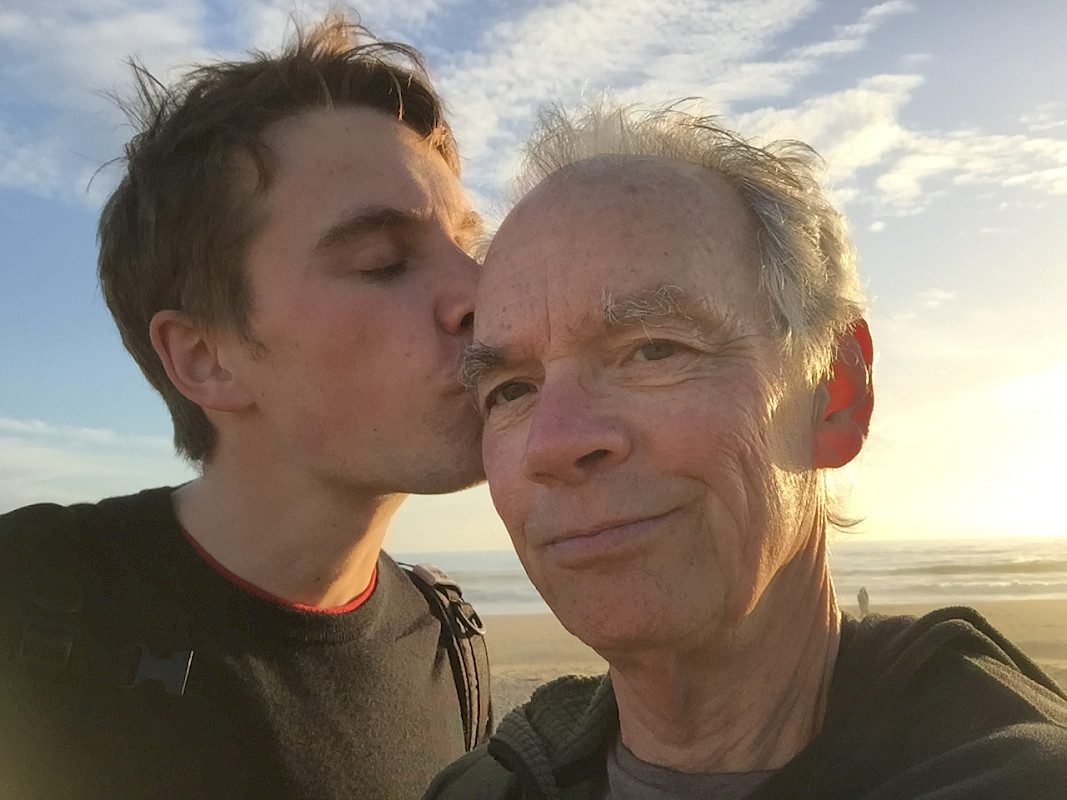

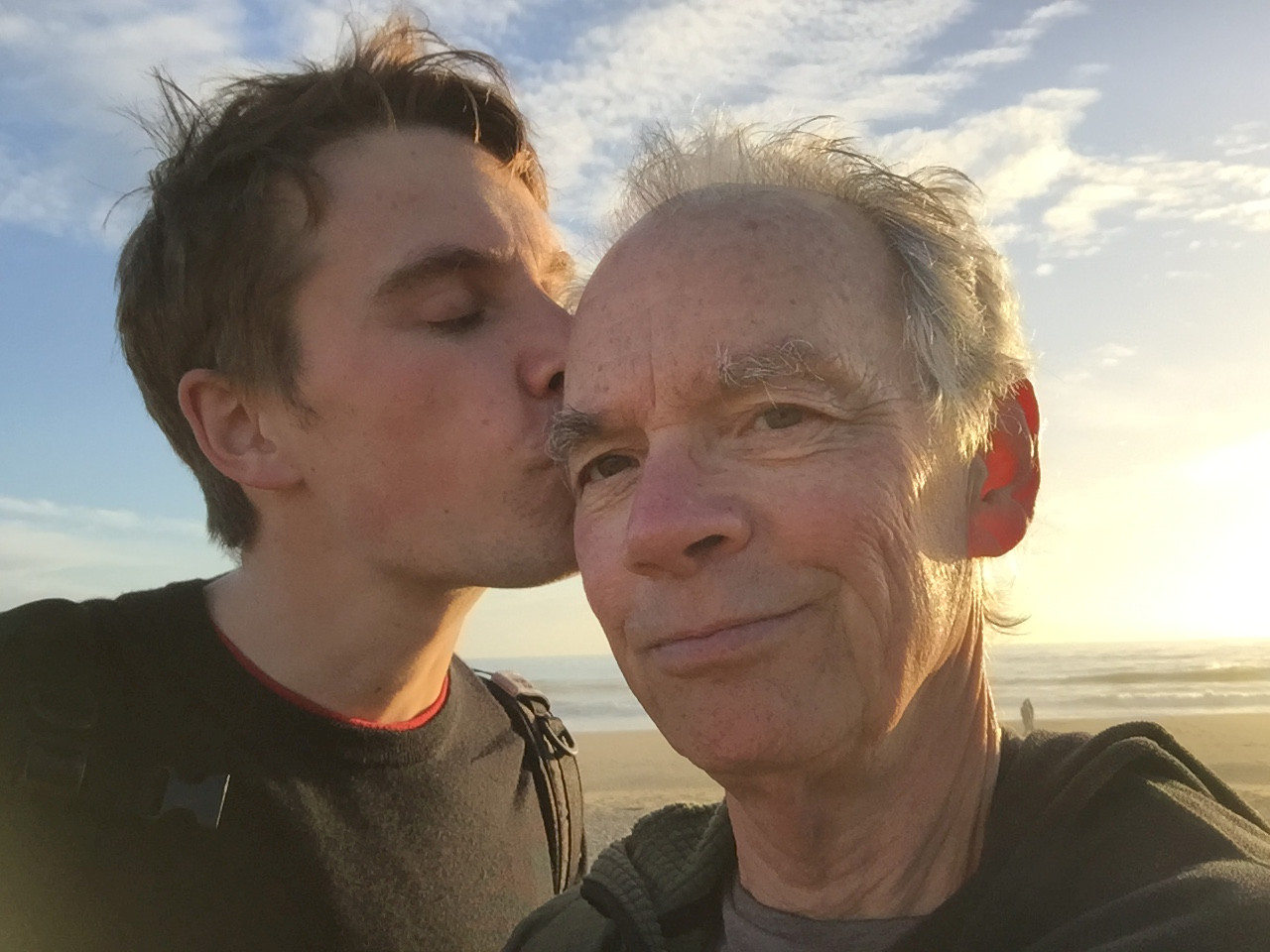

As the years go on my father continues to cry. This crying changes him. He becomes liquid, lucid, transparent, light. Within ten years he is almost unrecognizable. This tense, angry, scared man becomes someone clear, warm, kind, full of humor and love. The animal in his body at peace at last.

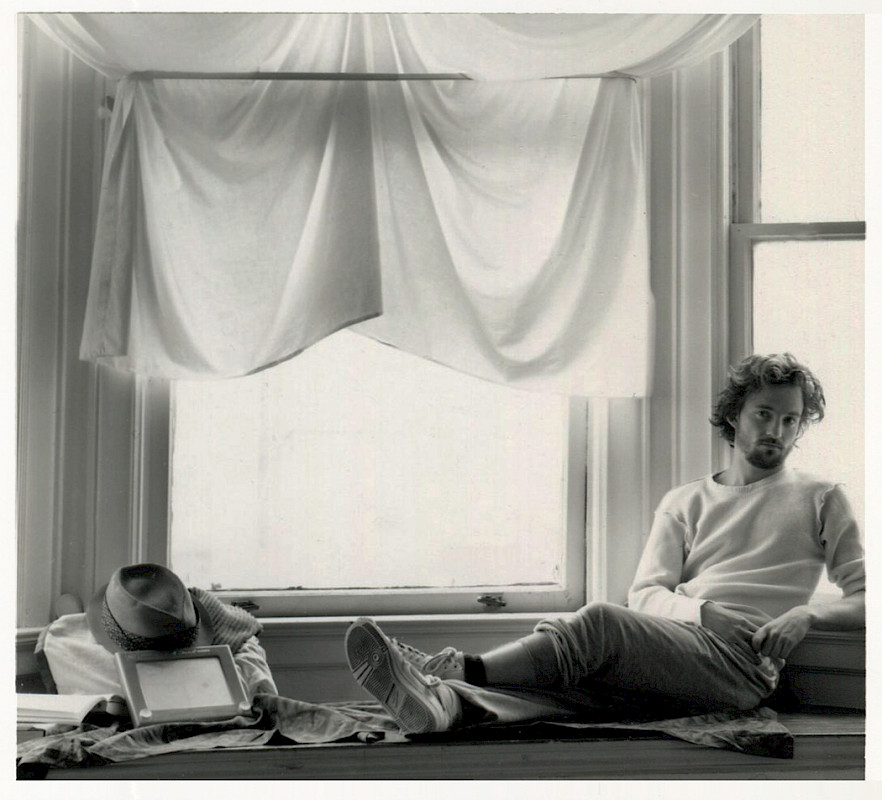

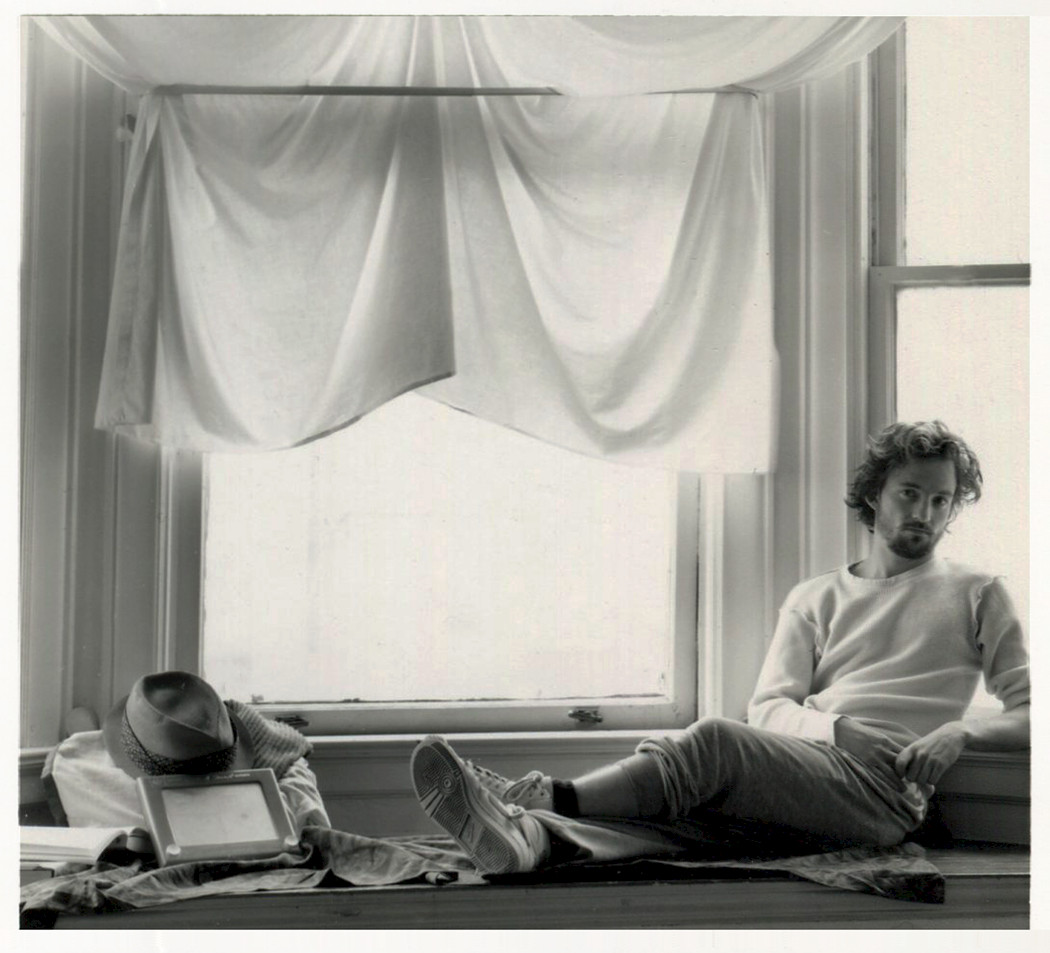

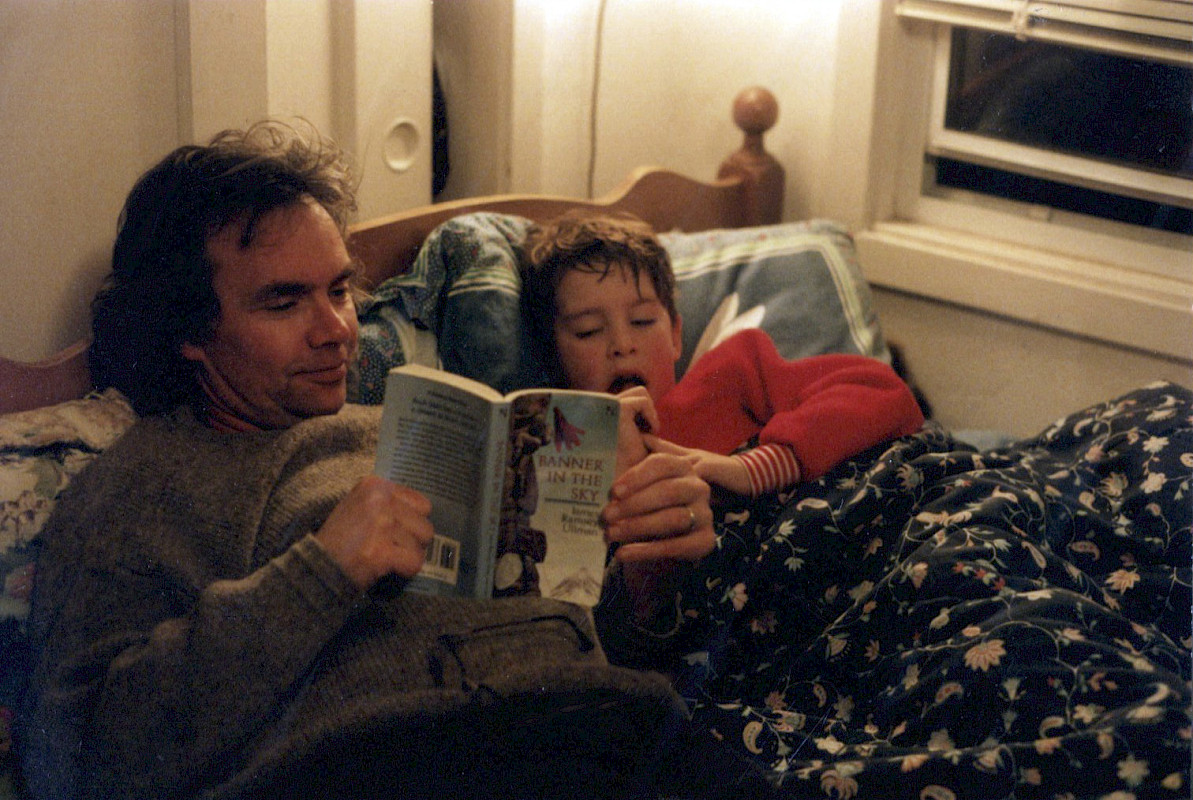

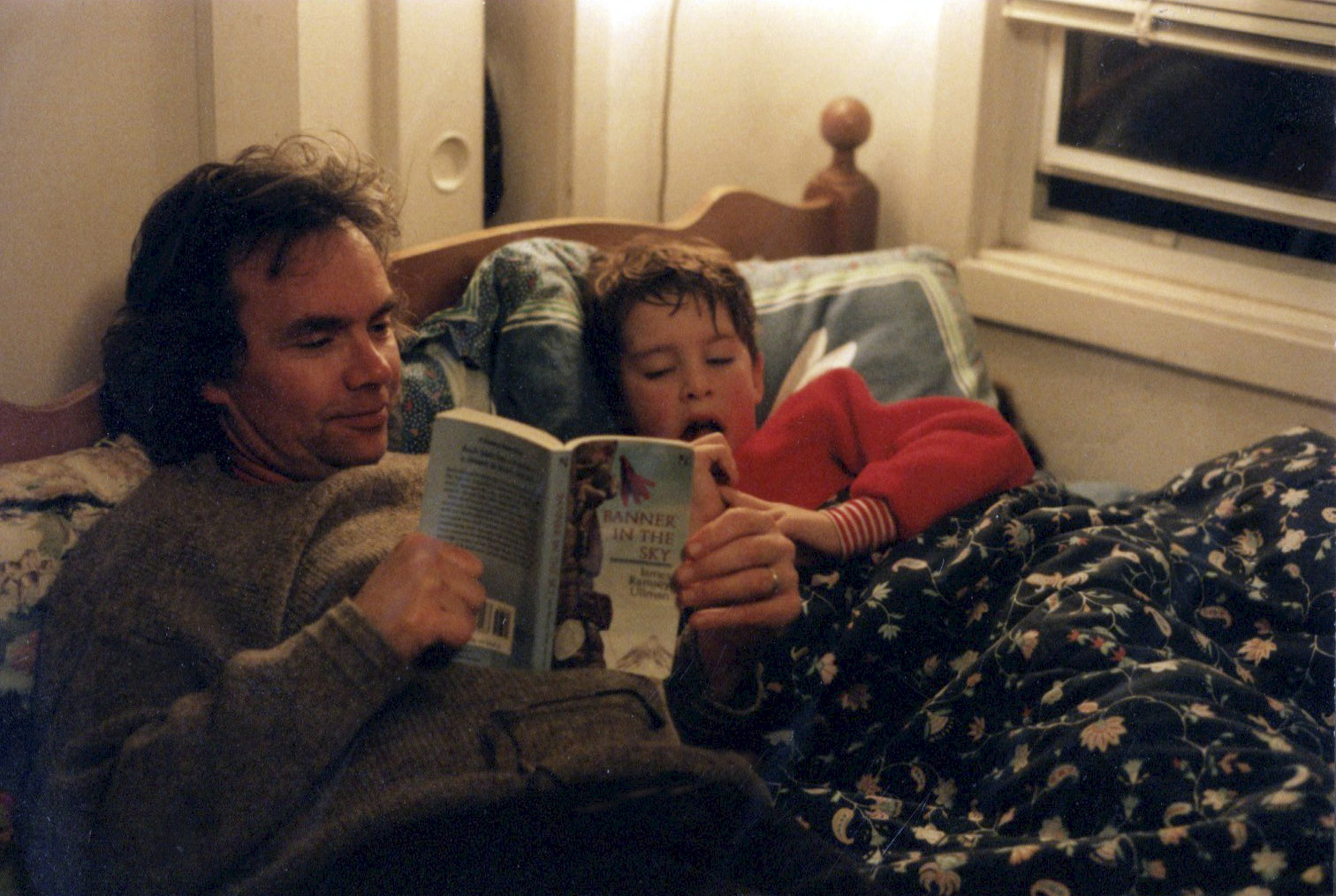

As I gathered photos for this project, I discovered that the story was perhaps not as linear as I imagined. Although my father was by all reports miserable during my pre-teen years, I was surprised and moved to find so many photos of his earlier life in which he looks joyful and alive.

1492.

Not the landing of Columbus on Guanahani and the beginning of centuries of murder, exploitation and slavery in the Americas. Something more local, here in Europe. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain.

Maybe you know the story. Many traveled to the Netherlands, where they were reluctantly tolerated. The rest traveled to Morocco and across North Africa. One of the main complaints of the citizens of Amsterdam and Tangier about their new neighbors was their constant singing and music-making. These Jews, they wrote, do not make images, in fact the creation of images is banned for them. Instead they rely on sung and chanted language as their means of prayer, celebration, and above all, mourning their dead. This disturbs the peace – why can’t they just be quiet?

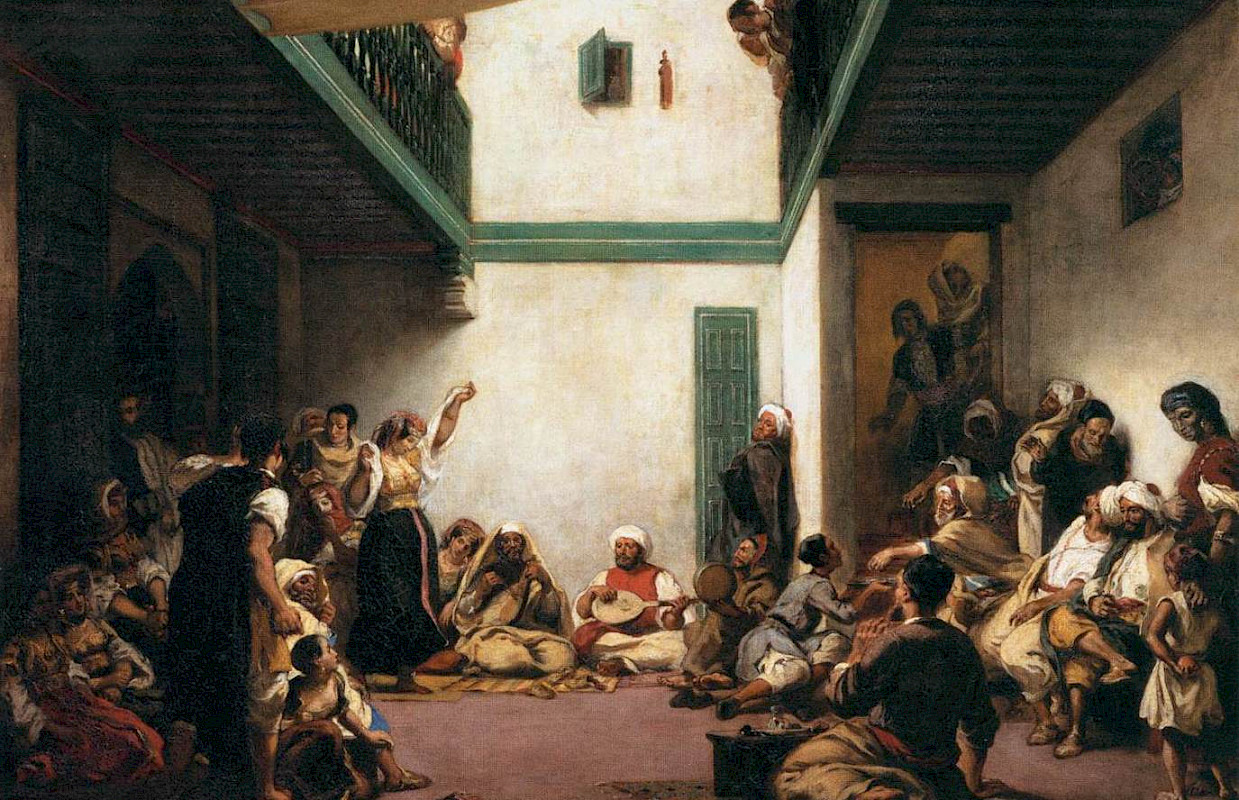

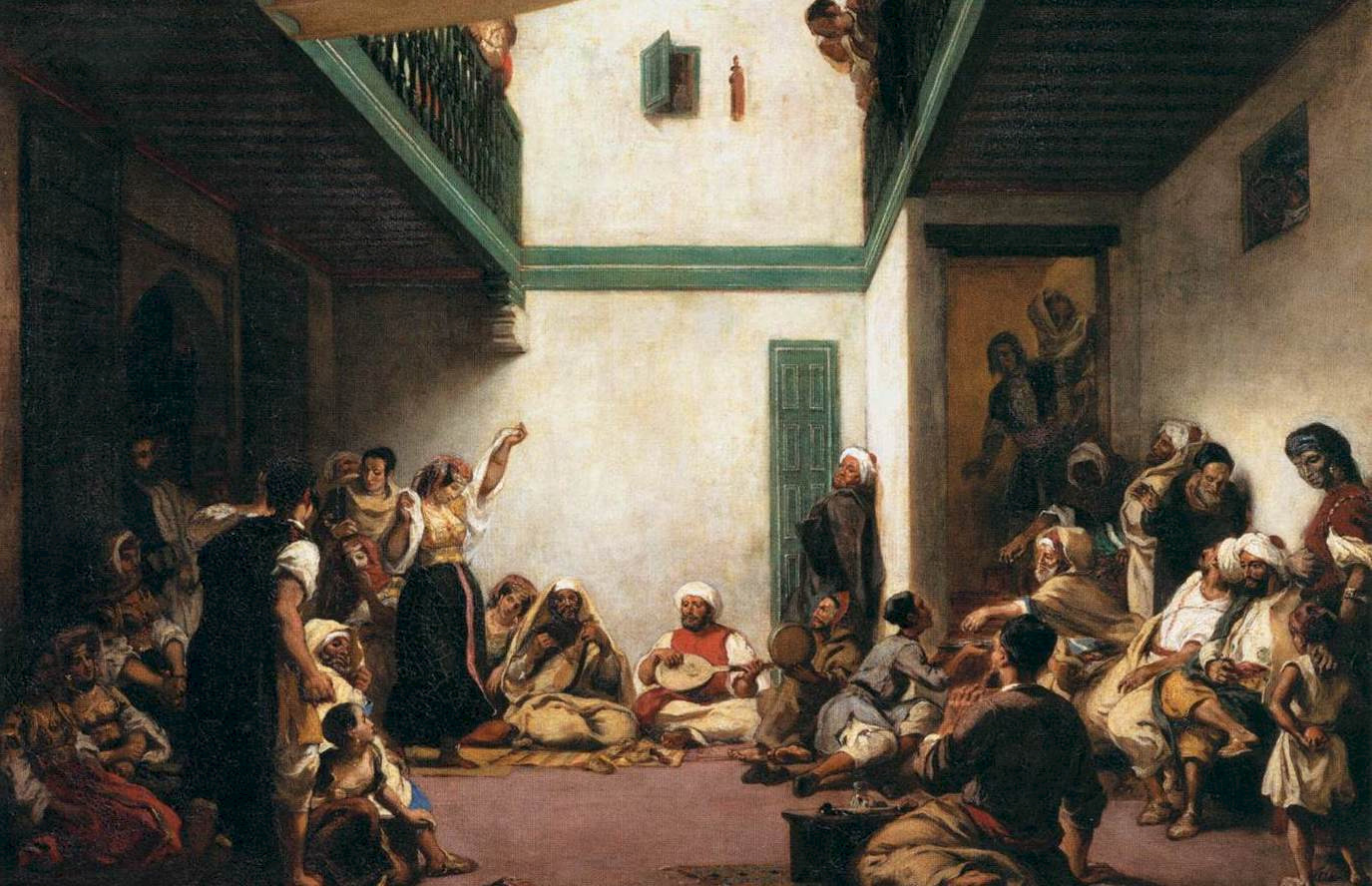

1841.

After returning from Tangier, Delacroix paints Jewish Wedding in Morocco in an orientalist Romantic style. In his travel diary, he mentions the constant singing and music-making of the Jews.

January 2017.

My father dies of pancreatic cancer. Before him my best friend, the first boy I loved, my two uncles, and my grandparents all die within a short time.

It’s normal. People die all the time.

Don’t get too interested in my story. I feel like everything nowadays is some person, some “me”, asking some “you” to care about my story, selling you my story. Making a coherent person out of all the chaos to convince you that I am valuable.

No. I refuse. It closes everything. Makes it small and dead. It’s exhausting, and has nothing to do with reality. This is not about my story. It’s not interesting.

What is interesting is that all these deaths were too much. I couldn’t cry anymore. I couldn’t mourn any of these individual lives, all the memories, all the details. I gave up on getting better, on getting over it.

Instead, a thousand tons of rocks. A seething black hole full of sound.

This fucked up situation we are in. The past and the dead – there’s always more of it, more of them. The present moment stretches out endlessly, it cannot be divided. And the future never arrives.

I wanted to feel into this chaos, hold my own head underwater. I couldn’t represent the dead theatrically or pretend to speak to them or tell you the story of my father’s life and how broken I feel without him. This agitation, this disconnection and pain. How much I loved this solid, warm, kind, and loving man.

I needed to obliterate myself, I needed to be overwhelmed, to go directly into it all – to disappear and be filled up with the dead and the past.

I started to search for a way to do this. Some word, some gesture, some sound. Most of all some sound – some tone to grab my ears and my heart, some invisible movement in the air. But I couldn’t find it. There was nothing I knew that matched this reality.

December 2018.

My friend Seraphina Goldfarb-Tarrant sends me this text:

the dead and animals will remember the smells of cabbage and water. </s> i have no idea what is happening , and what i have to say is that i can not bear to be a man . </s> this is the only place where the dream is the sound of the dead man’s initials . </s>

These words grab me, stir something deep in my chest and my spine. I want to sing them. Get them into my body, see where they lead.

Seraphina tells me that this text was generated by an Artificial Intelligence, an AI, a Natural Language Processing system. (This is four years before ChatGPT). She built this AI system, then broke it intentionally, so that it would produce fragmented text.

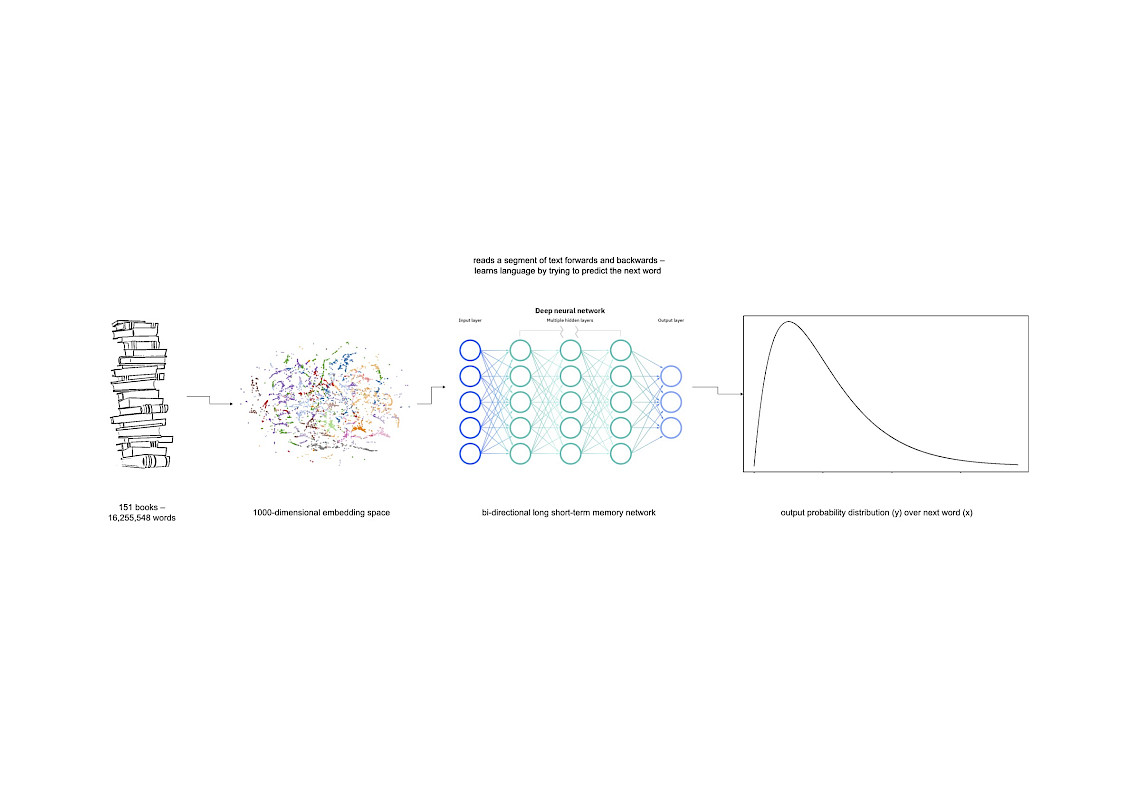

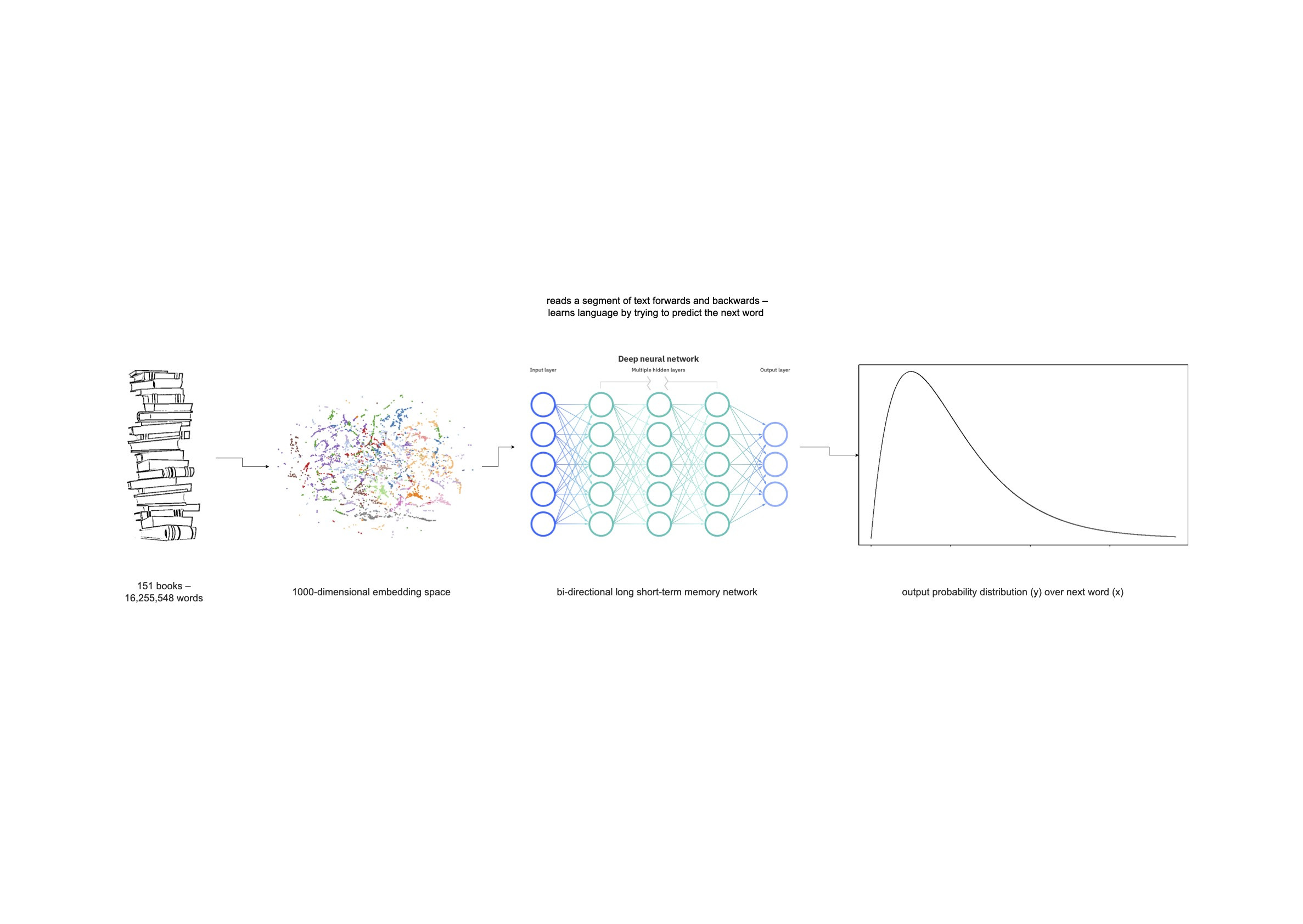

Seraphina explains that an AI system is not a persona or a presence or a thing. It is an archive, a huge amount of text – books, poems, bits of the internet, letters, diaries, whatever you choose. Like the words in the Talmud, the words are converted into numbers, then they are mapped in a 1000-dimensional mathematical space, and processed through an algorithm. When you give the system a prompt it predicts what words it should respond with based on all the text it has been fed.

It is a material system for processing the past, nothing more. Old words in a new order. It is built from human choices and human labor. It is not the robot apocalypse.

I realize that this is what I have been looking for. A way of turning towards the past, listening to the dead voices... infinite words, infinite inputs, infinite outputs, for the infinite dead... turning the voices into something dense and overwhelming that I can’t quite grasp but that I can let into my body.

January 2019.

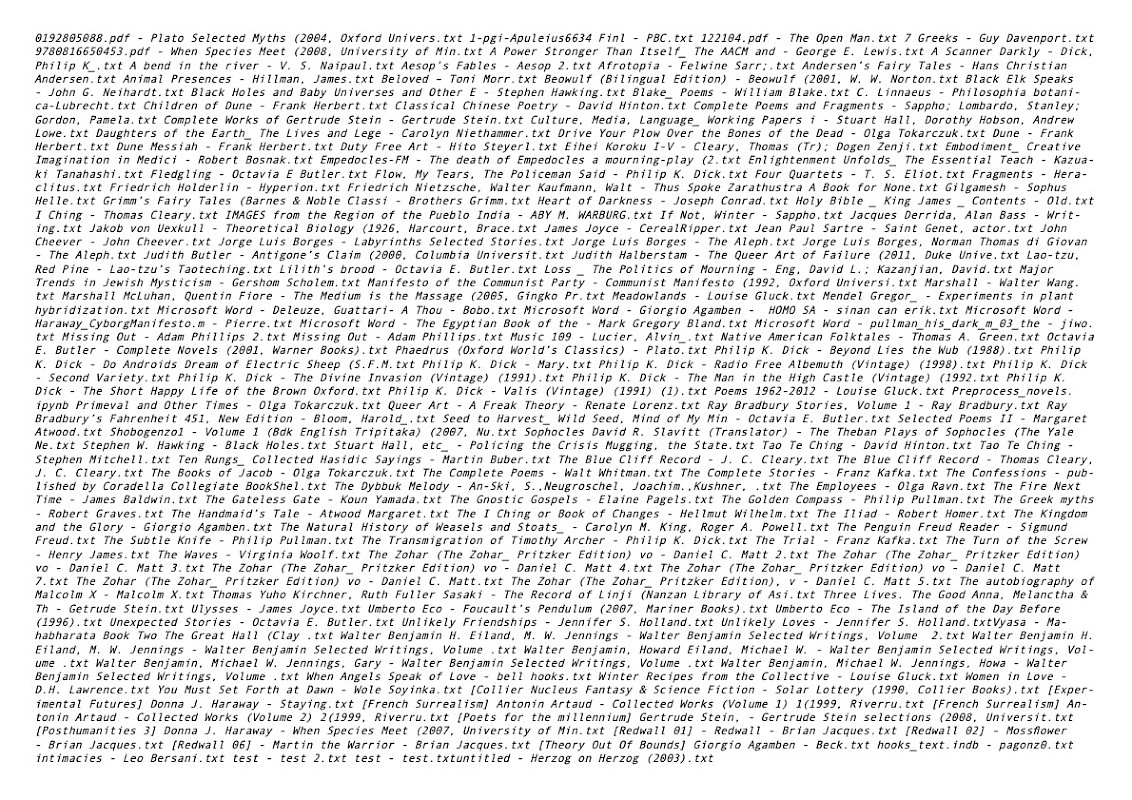

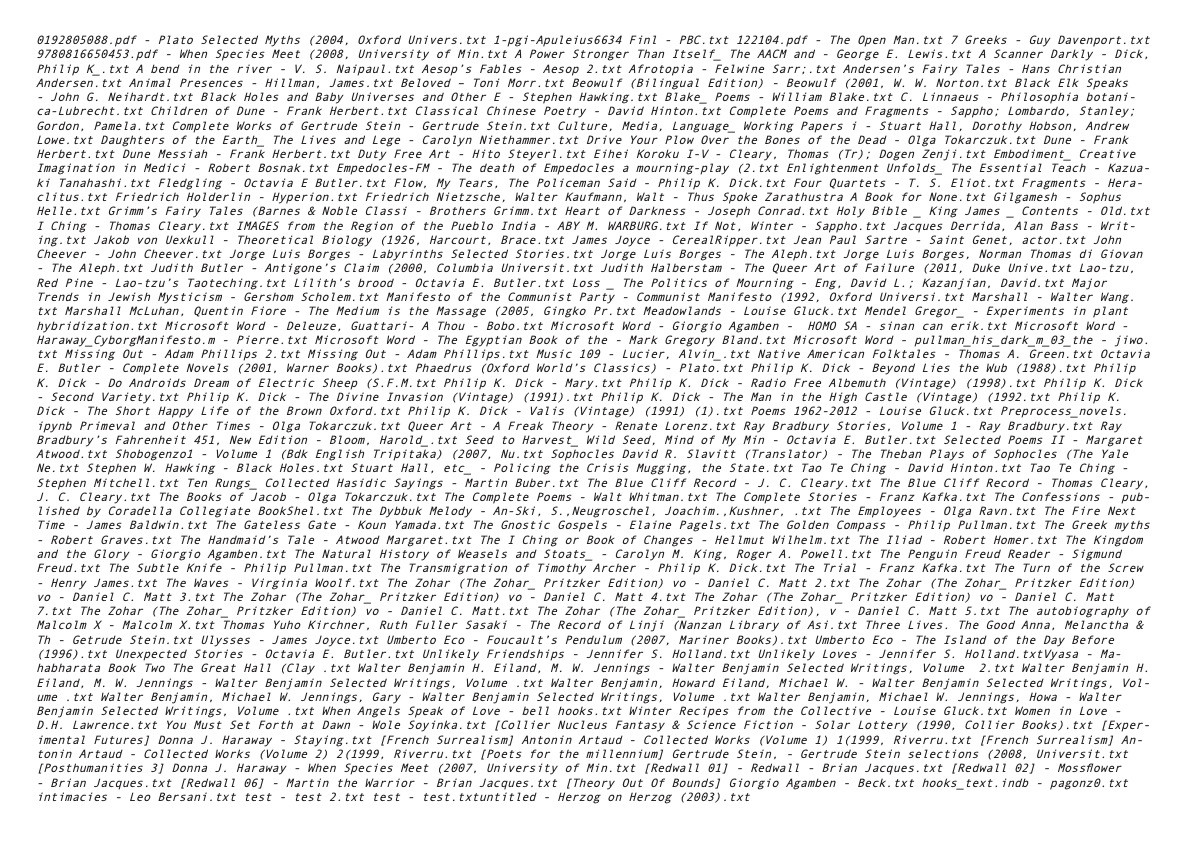

Seraphina, our friend Alejandro Calcaño and I choose 151 books whose authors’ voices we want in our system. Novels, science fiction, critical theory, poems, speeches, religious texts. The diaries of our dead friends and family members, children’s books.

Seraphina programs a language model and trains it on these books.

It’s a very specific dataset, not aiming for anything universal. Books that we loved. The more specific the dataset, the more it becomes clear how the system never quotes, but is full of ghosts of the sentences of past authors, but also of fragments and words that belong to no one.

I prompted the system with questions like “do dogs still mourn after 7 years” or “where is my father now” or fragments or even just one word like “no” or “weasel”.

I picked sentences and paragraphs that moved me, always selecting, never editing. I started to sing these words. I invited my friends Carmen and Ariadne, who had had their own losses in the last years, to join me. Later we invited my uncle Wayne, my father’s brother. We made music from the words and from this music we made a performance called GHOST.

I want to be clear. I did not come to this AI system looking for answers to my questions about death. An AI system does not think. It is not a person or a presence. When I put in “where is my father now?” the system just predicts what words should come after these words, based on the data it has been trained on. Anything else I add onto it is pure imagination.

It’s like the Rabbis say – the dead are not images or their traces in the material world. They aren’t spirits and aren’t darkness or ghosts or History or even what we call the dead.

My father’s ashes in an envelope. Anything added to it is pure imagination.

AI Art. It brings a lot of baggage, a lot of expectations, a world of fantasy.

For example I could use AI to speak to my dead father, AI as Oujia board, AI as seance, AI as ghost. Or use AI to create a vision of a future utopia, perfect harmony between humans and machine and nature in a genderless robot socialist state. Or AI as a clever personal assistant, funny and moving answers about death at the right moment, with a well-designed animation. Or AI as something spectacular, huge, loud, impressive – The Terminator, AI as apocalypse, Jesus, all-powerful, Christian AI, the Revelation, the end of time, fire and the seven-headed beast. Or AI as a nightmare of gender cliches. The deep scary voice of a man who will take over the world, the sexy comforting voice of a woman who will take care of you. I could go on…

I have come to hate AI because the imagination around it is too strong. It shows us how we cannot help but bring our imaginations to what we see. It shows us how we cannot see the thing itself.

In the last few years I learned that many AI artworks I saw, in which AI gives random yet perfect answers at the right moment are faked, pre-programmed by humans, fine tuned to the fantasies of the makers.

I too fell into the temptation to add things to the system, to try to make it “interesting”, to fit it to my fantasies.

I made many versions of this work, trying and failing to find the right relation to this thing. In 2019, a performance in New York, with the AI system personified as a man named LUCAS. In 2020, a performance in Amsterdam, LUCAS became an invisible oracle, a guide, offering abstracted answers about death. In 2021, fed up, I tried the opposite, a performance in Antwerp in which we prompted the system for 4 hours and sang the responses live. And even then we kept asking ourselves – does the AI system have a name, what does it really think about death? What is it thinking when you don’t ask it a question?

I was not alone in this struggle. The whole world is trying to figure out how to relate to AI right now, struggling, above all, to see it for what it is and what it is not. It seems it is almost impossible for us to do this.

For this reason I had to kill it. This is why the AI system had no place onstage in our performances.

What remains is the words that it gave us. Words that opened our hearts and gave us a feeling of being with our dead and with the dead in general. Words that my friends and my uncle and I speak and sing, in the performance, and in the recordings.

2023.

Sitting for seven days and seven nights together after a death, lying on the carpet of a living room in California, sitting in the corner of a loft in New York City, an old theatre in Utrecht, a silver warehouse in Vienna, the basement of a nightclub in Amsterdam. Speaking and singing as a way to be with the dead, singing as listening. The room fills up with memories, the dead aren’t gone. And for a moment we’re just a lot of words from the past, arranged in a new order.