essay

Are TikTok Healers Contemporary Quacks or Re-risen Witches*?

Fedora Boonaert

Fedora Boonaert is an art historian and designer concentrating on the relationship between (lost) botanical knowledge, woman healers and the witch-hunts in the sixteenth-century Low Countries. She holds a Master's degree in Art History from Ghent University and has recently graduated with her second Master's degree in Contextual Design from Design Academy Eindhoven.

Rustan Söderling

music

Singing To The Machine: Orpheu The Wizard

This mix by Orpheu The Wizard consists of a selection of songs loosely revolving around the themes of Mystics of the Chthulucene. First up in a new mix series, where artists, selectors, and music geeks connect sounds to a broader and recurring artistic research theme that weaves through The Couch.

essay

The mindless sc/troller

If the postmodern (digital) experience is a similarly disorienting experience to that of the modern flâneur, then is it possible to adopt the same approach to the web as to the city, where the mind can freely wander and transform?

essay

Mystics of the Chthulucene

Cthulhu – H.P. Lovecraft’s science fiction monster – lurks under the surface of the ocean as an elemental deity. We must wonder what lurks beneath the surface of the systems known as AI.

essay

POV:

Ginevra Petrozzi makes the case for a complicated relationship between ourselves and the artificial intelligence tools that guide us through our lives. The stories and myths we construct around the technologies we don’t understand can help us navigate the obscure and even violent power of artificial intelligence.

20

min read

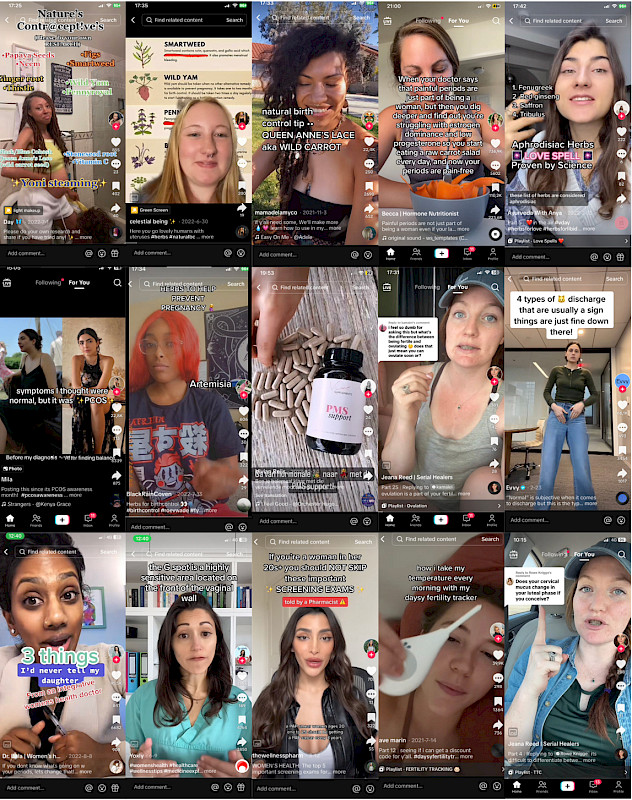

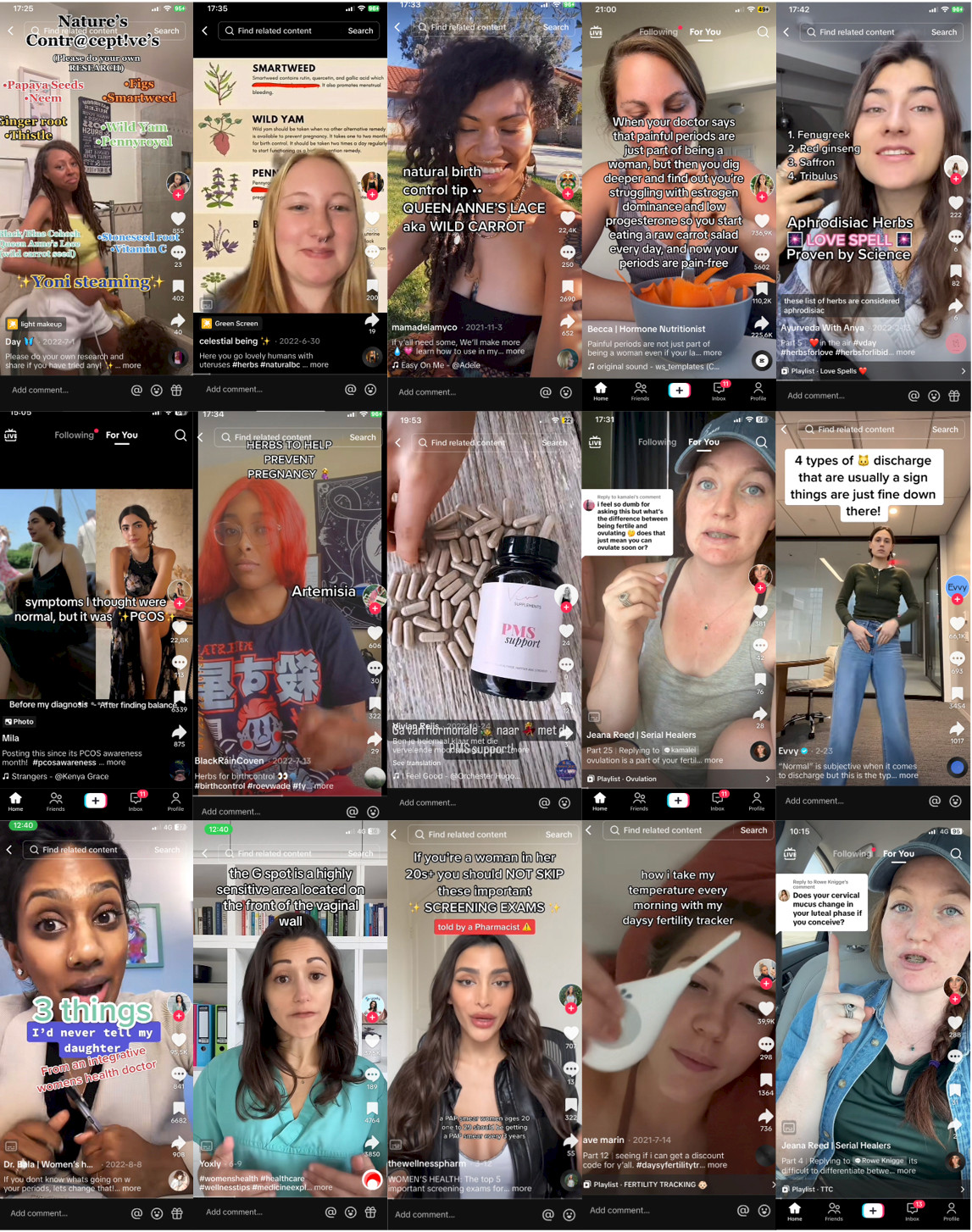

Every once in a while, in the midst of a midnight panic attack, I find myself scheduling an appointment at Dr. Google’s virtual medical office. It often starts with a mild pain somewhere in one of my left toes, but as I then deep-dive into the virtual rabbit hole of medical information, I somehow manage to diagnose myself with an improbable combination of being pregnant with triplets, having four life-threatening STDs, and possessing an exceedingly rare hormonal disorder afflicting only 0.005% of the general population. Only, with the recent emergence of TikTok healers, a new competitor has arrived in Virtual Advice Town. While the Google search bar opens the door to an overwhelming sea of information and possibilities, your TikTok feed offers something distinct. The algorithm seems to guide you right towards the advice you specifically need – or that you didn’t yet know you needed. That advice is mostly given by self-proclaimed healers, often women, considering themselves re-arisen witches* (1). The short videos they share on the platform can vary from “train your pelvic floor”-workouts to “DIY herbal remedy”-tutorials to “learn everything about your menstrual discharge”-lessons. What sets them apart is their empathetic approach. TikTok healers build personal connections with their followers; by sharing intimate stories, interacting in the comments and even conducting live Q&A sessions where they address viewers' concerns in real time. This enhances their fans' feelings of being heard, of being understood.

Clearly, I am a professional hypochondriac – but I am not the only one paying regular visits to the online helpdesks. As healing hashtags such as #womenshealth, #herbalism and #comingoffthepill are trending, it is clear that many others, too, again, mostly women, are turning to social media platforms in their quest for medical reassurance and guidance. Something the virtual medical landscape – in contrast to the physical one, sometimes – seems to offer. Yet this online advice does not go without any risk. Self-diagnosing via the Internet carries several potential dangers, such as encountering inaccurate information, ordering ineffective or even poisonous medicines, fearing rare conditions disproportionately and exacerbating health-related concerns. In other words, paying visits to online helpdesks holds the risk of falling into the trap of quackery. In the past few years, we have seen many initiatives addressing the pitfalls of Dr. Google. Health authorities such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) have launched information campaigns to make people aware of the dangers of unsubstantiated medical information on the Internet and worked together with search engines such as Google to ensure that search results for medical queries show reliable and validated information (2). With the rise of TikTok, we are facing new challenges, as a new online unregulated space has opened up where quacks can have free rein.

Why do so many people, despite its obvious dangers and nefarious consequences, still turn to the Internet to seek help and entrust their lives to re-risen witches*/quacks? And why are they all primarily women? In this essay I will dive into the sixteenth-century Low Countries (encompassing present-day Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) to explore the historical roots of the persistence of (online) quacks and witches*, examining how their exclusion from the official medical landscape is forcing them to continue to operate while repeating the same mistakes as 400 years ago and causing new harm.

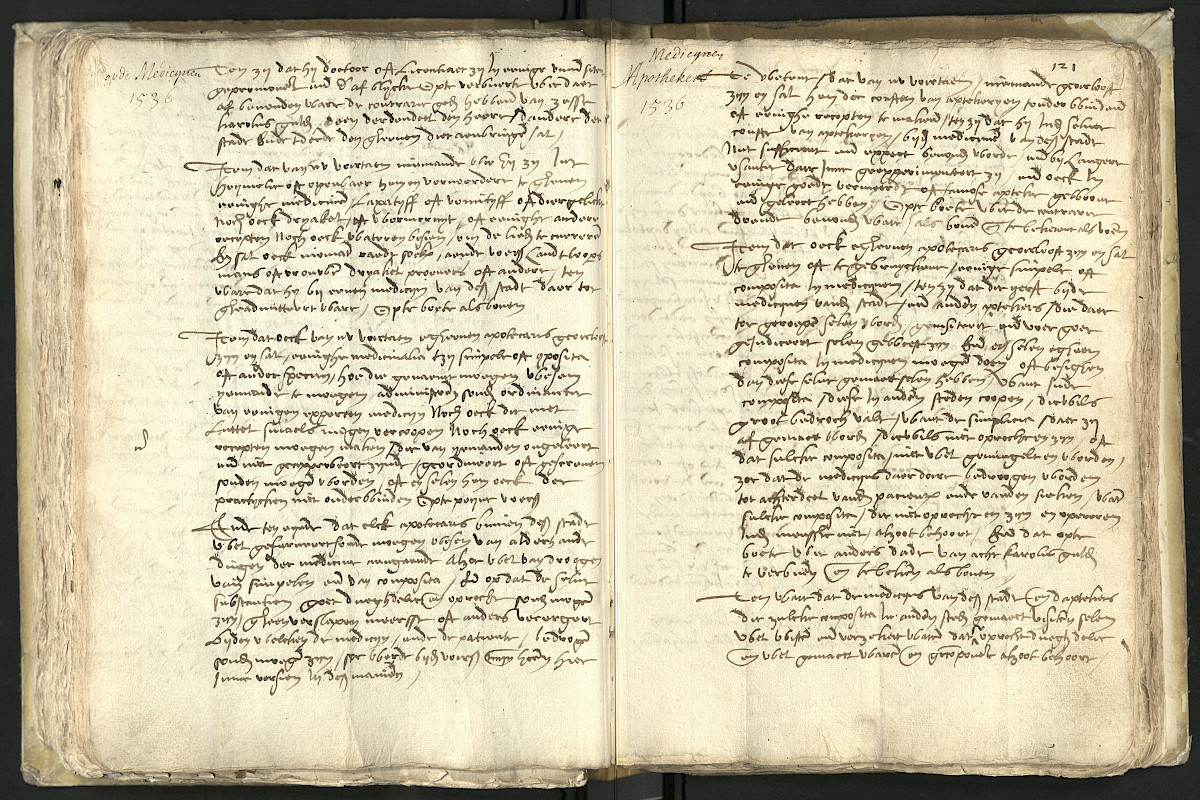

Why are we taking advice from Quacks and Witches*?

The term "quack" not coincidentally finds its origin in the sixteenth-century Low Countries, and is derived from the Middle Dutch word "quacksalver" (modern Dutch: kwakzalver), a contraction of quack (“to croak”, modern Dutch: kwaken – like a duck) and salve (“ointment, salve”, modern Dutch: zalf). It referred to individuals who, according to the authorities, falsely “croaked” to possess certain medical knowledge or skills and were peddling fraudulent drugs. In hindsight, the emergence of "quackery" in the sixteenth century follows logically as there was a growing trend towards the scientification of medicine in universities. This shift led to the institutionalisation of healthcare and the establishment of a clear division between accredited and unaccredited services. Consequently, traditional folk medicine practices were deemed deceitful and continuing to perform them became punishable.

The limited knowledge that did survive, underground, became unreliable and risky, indeed potentially leading to harmful quackery.

Of course, during this era, women were excluded from universities. Female traditional healers, who had long been highly respected members of their local communities, were no longer authorised to practice their professions. Their knowledge of herbal birth control and aphrodisiacs had been orally transmitted over generations and was therefore excluded from the official medical curriculum and began to fade into oblivion. This exclusion installed a male-centric system, neglecting women's needs, that continues to persist to this day. The limited knowledge that did survive, underground, became unreliable and risky, indeed potentially leading to harmful quackery. Despite there undeniably being individuals selling nonsense for profit, people in need of specific care that was not provided by the official institutions had no other choice but to turn to individuals operating in the illegal realm, even though it carried risks.

The rise of quackery during the sixteenth century in the Low Countries went hand in hand with the onset of the witch hunts, which had spread across Europe and now also took root in the Low Countries. As the divide between scientific and non-scientific knowledge became increasingly distinct, the penalties for quackery grew harsher. Traditional female healers who continued to practice underground became one of the many targeted groups falling prey to the witch hunters (3). More precisely, these women were accused of preparing a so-called “flying ointment,” made with the fat of unbaptised babies and magical herbs. After smearing the substance onto their broomsticks, they were believed to fly to witches' Sabbaths and engage in sexual acts with the devil. Legends of witches and their supposed "magic," could often be attributed to hallucinatory experiences due to overdoses of herbal birth control. All of these mystical narratives, concocted by witch hunters, allude to practices related to sexual health, including the preparation of aphrodisiacs, contraceptives, and abortive remedies. These much-needed treatments not only were excluded from the official medical care provision, but they even were condemned as malevolent sorcery and were persecuted with fatal consequences, as many women died at the stake (4).

Today, traditional woman healers are still present – in many different variations, from many different backgrounds – and some are boldly reclaiming the "witch*" label, for example on platforms like TikTok. This movement aims to revive the lost knowledge, or what remains of it, and offers the care that mainstream healthcare still fails to provide. Our medical infrastructure continues to be deeply male-centric, on many different levels. The biggest clinical studies only include men as test subjects, causing belated diagnoses and harmful medicines to be taken by women; there is only little funding to research female-specific diseases. Contraceptive methods are having major effects on women's health and nothing is done about it (5).

It is therefore logical that, just as in the sixteenth century, women continue to turn to (online) alternative healers, as there are no other options available, even though it is unreliable and risky. Especially in contexts where abortion laws are restricted, such as in Poland or certain states in the US. However, it's crucial to acknowledge that drawing a direct line from the sixteenth-century Low Countries to today's TikTok healers isn't as simple as connecting historical dots.As an art historian, my research predominantly concentrates on that period and region, but the ‘knowledge’ showcased on TikTok comes from a global web of cultures. It reflects a complex network of global and local knowledge exchange that spans centuries. Nonetheless, it is valuable to make the comparison, to get an understanding of the mechanisms still at work today.

What advice are we looking for?

Not only am I a professional hypochondriac, but I'm also skilled in the art of TikTok scrolling. Within my personal feed, you'll find video after video (interspersed with an occasional make-up tutorial, quirky giraffe antic or astrological analysis of certain movie characters) from self-proclaimed healers sharing a wide variety of information. Mostly, in my case, this includes medical advice revolving around young women's health – as the algorithm is tailored to my 24-year-old female body. A quick survey of my feed shows us the following:

- DIY methods for herbal birth control

- Information regarding the G-spot

- Tips to help recognise certain conditions such as PCOS and endometriosis

- Q&A’s where online healers answer their followers’ questions

- The meaning of your menstrual discharge colour

- …

TikTok healers come in many shapes; some wear white coats and wield stethoscopes, while others are comfortably dressed in pyjamas on their couches – they each bring their unique approach. However, they do have something in common. What binds them all together is their willingness to openly share personal stories, creating a sense of connection with the audience. This stands in contrast to your regular doctor's appointment, where you – or at least I – are often receiving cold, impersonal advice. Through TikTok's interactive features, like liking, sharing, commenting, and stitching, a community is created. Within the confines of a short video, TikTok healers manage to build a unique bond with their viewers, positioning themselves as listeners and establishing an empathetic approach. This results in a safe space where people are not afraid to ask their questions, often anonymously since people can hide behind a chosen username, such as @kamalei asking “i feel so dumb for asking this but what’s the difference between being fertile and ovulating ???? does that just mean you can ovulate soon or?” (Author’s note: @kamalei, you are not dumb.) Empathy and time are abundant on TikTok, qualities our regular healthcare services frequently lack. When people are not listened to by their general practitioners and are left with particular problems or have questions that they are afraid to ask, they can find solace online.

Empathy and time are abundant on TikTok, qualities our regular healthcare services frequently lack.

There is clearly a whole body of knowledge still not (sufficiently) included within the medical field, both in terms of care provision and education. For 400 years now, this information has been orally transferred through non-official channels, as it is the only way people can get access to it, even though it’s desperately needed. TikTok has become a platform where such content is shared by women as a means to educate other women. Awareness is raised of conditions such as endometriosis and PCOS – thank you @mila – which are often overlooked by general practitioners. Knowledge is shared on how to recognise specific signals of your body, such as the colour of your vaginal discharge – thank you @evvy – something that I for example only briefly learned before, if not at all.

Misinformation disguised as wisdom

Alongside the generous knowledge shared amongst women, we see, for example, a whole anti-hormonal treatment movement rising on these platforms. It warns of the disastrous effects of hormonal contraceptives – such as becoming infertile after 10 years of using the pill. That information, however, is absolutely false: you DO NOT become infertile after using the pill. TikTok stirs up the danger of self- and misdiagnosis, leading to panicky hypochondria and even unwanted outcomes. It is oral knowledge, which holds the same pitfalls as 400 years ago: the transmission does not always run smoothly, allowing pernicious errors creep into the discourse.

TikTok healers often get the information they spread from TikTok, making those falsehoods reproduce themselves.

The difference today is that it is happening on an unprecedented scale. While Google's influence could still be somewhat contained, the pendulum has now swung entirely in the other direction. TikTok healers often get the information they spread from TikTok, making those falsehoods reproduce themselves. In an attempt to combat this issue, ‘licensed’ doctors are warning about that misinformation on TikTok – but they cannot overrule this ‘(mis)knowledge’ as it exponentially spreads hyper-fast since all these TikToks go viral. On top of that, our scrolling happens at such a fast pace that our critical ability cannot keep up and cannot distinguish between what is true and what is not. Some self-proclaimed healers wear white coats, while some 'official' doctors wear pyjamas, and vice versa – this creates confusion. Consequently, the line between 'certified' medical professionals and self-proclaimed ones becomes increasingly blurred, forming a wide spectrum in between.

In this digital age, TikTok has emerged as a complex arena where users navigate a mosaic web of information, misinformation, and confusion. While many creators on TikTok have good intentions and the platform serves as one of the few channels for sharing essential knowledge, including valid information that demands urgent attention, TikTok has acquired a reputation for hosting questionable content. This reputation inherently undermines the credibility and legitimacy of information shared on the platform, automatically blocking its development. On top of that, the backfire effect, a psychological phenomenon in which people tend to believe even more strongly in misinformation after they encounter an evidence-based correction, makes it even more difficult to distinguish valid and questionable content on the platform.

DIY Herbal Remedies

Many modern pharmaceuticals are originally derived from plants. For instance, aspirin, originally derived from willow bark and meadowsweet, evolved into its current chemical form through centuries of research and experimentation. This raises a thought-provoking question: What if herbal remedies for birth control and related purposes had been integrated into the official medical curriculum rather than being pushed underground? Could the inclusion of herbal knowledge in the past have led to the development of non-hormonal contraceptives derived from plants, with their botanical ingredients now synthesised into safe and effective forms? We don't have an answer to this question. Today, there remains a lack of proper research and development grounds for these herbs to be transformed into legitimate medicines. However, on platforms like TikTok, people attempt to pick up the thread and continue the experiment.

For instance, @Day suggests Yoni steaming as a contraceptive method, incorporating ingredients like papaya seeds, neem, figs, smartweed, ginger root, thistle, wild yam, pennyroyal, stoneseed root, vitamin C, black/blue cohosh, and Queen Anne’s Lace. @celestial being ✨ recommends smartweed and pennyroyal for natural birth control, and @mamadelamyco also mentions Queen Anne’s Lace for this purpose. @BlackRainCoven suggests Artemisia to prevent pregnancy, while @Becca claims that consuming a raw carrot salad daily can alleviate period pain.

What if herbal remedies for birth control and related purposes had been integrated into the official medical curriculum rather than being pushed underground?

What's striking is the overlap between the herbs advocated by these TikTok healers and those that played pivotal roles in my research on herbal practices during the sixteenth century in the Low Countries. Herbs like smartweed, ginger root, thistle, pennyroyal, Queen Anne’s Lace, and Artemisia, recommended by contemporary TikTok healers, were also used back then for their abortive, contraceptive, and aphrodisiac properties. Notably, John M. Riddle published scientific confirmation in his book Eve's Herbs - A History of Contraception & Abortion in the West that these plants, tested on rats, indeed contain active substances with these properties (6).

TikTok healers draw upon the survival of this historical knowledge, knowing the plants but not the precise recipes – as they were not included in the official medical curriculum, became prohibited, and were forced to be passed down orally in non-regulated spaces. While these herbs are no longer illegal today, they still lack a regulated environment for development, carrying the same potential dangers. Engaging in DIY herbal remedies without expert guidance can lead to dangerous outcomes, as the efficacy of these treatments is grounded in accurate preparation and dosage. On one hand it can lead to overdoses and straight-up poisoning, on the other, it can enhance the belief that a herb that has gentle properties is a foolproof method – like @Becca claiming eating a raw carrot salad every day will solve your period pain forever (disclaimer: it will not).

The relegation of herbal birth control to the illegal sphere led to the inaccurate transmission of knowledge and a halt in the development of safe herbal remedies, inadvertently causing harm. We now find ourselves restarting the process of developing herbal remedies, attempting to pick up the thread that fell 400 years ago. However, in this process, we remain trapped in repeating the same mistakes. Herbal birth control continues to be forced to develop in non-regulated spaces, fostering misinformation and causing new harm. Without official recognition and a safe testing ground, catching up with 400 years of scientific development becomes nearly impossible.

Capitalism and wellness culture

In the sixteenth century, the underground world of healthcare was a mixed bag. Alongside well-intentioned healers who genuinely sought to help, there were also those who peddled miracle remedies and services on marketplaces purely for profit. The most notorious of these was "dryakel" or theriac, a supposed panacea that combined various ingredients into one remedy, often causing more harm than good. It is not surprising that authorities in the sixteenth century, like those in the city of Mechelen (where my research has been focused) harshly acted against its distribution, dismissing it as quackery (7).

Today, a parallel can be drawn with the online shopping mall that TikTok has become. Many online healers are making substantial money by selling mysterious cures and supplements with questionable efficacy or even harmful side effects whose long-term consequences remain unknown. For instance, individuals with serious medical conditions, such as cancer, may fall victim to quack therapies, such as treatments with essential oils and refuse proven treatments like chemotherapy, resulting in dire consequences.

It's crucial to recognise that drawing a clear line between well-intentioned healers and profiteers, or between quacks and re-arisen witches*, is often impossible, as both contribute to the same problem and often overlap. TikTok has evolved into a platform of performative empowerment, where well-intentioned or not, empowerment often flows into consumerism. Self-proclaimed healers are not operating on their own, often there is a thriving industry behind them. Our contemporary wellness culture perpetuates the idea that we need a full bathroom cabinet of products to maintain our health, often exaggerating the effects of certain ingredients and sowing fear of certain conditions leading to the purchase of a particular wonder product – read nonsense capsules (thank you @Vivian Reijs). On top of that, collaborations are formed with other (non-healer) influencers who lack expertise, endorse products and misinformation, sometimes without researching the risks they pose. The empathetic approach and manufactured close connection between online healers, other influencers and their followers make these products sell like hotcakes.

The newest gadget in TikTokland is the Daysy® cycle tracker, a device to track your fertile days and predict your ovulation by measuring your temperature every morning. @Ave Marin can get you a discount code if you want! Many influencers promote this new tool, using performative empowerment as a marketing strategy, praising a substitute for the big culprit: hormonal contraception. Not only is this extremely expensive, it is also totally unreliable. It has recently come to the attention of the Dutch government (Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd) that the rise in such alternative methods has already led to an increase in unwanted pregnancies and abortions in the Netherlands, as these remedies are not effective (8).

Another concerning trend is the promotion of yoni steaming, popularised by celebrities like Kourtney Kardashian, who claimed to have conceived through this method. This has led to a surge in the practice, even though it can cause damage as the hot steam can be harmful to your labia and the herbs can interfere with your vaginal pH (source: a ‘licensed’ doctor on TikTok – at this point I do not know anymore either).

The bottom line is that there is a clear gap in our healthcare system. Many women are seeking alternatives to hormonal contraception, hoping to alleviate painful period cramps, searching for ways to enhance their libido. Yet our conventional healthcare system does not offer these services, leaving a void in the market that opportunistic individuals, reminiscent of those in the sixteenth century, are eager to exploit for financial gain and do not care about the consequences.

An emergency call

The rise of TikTok healers put a new twist on how individuals seek and receive health information. With the rise of social media, access to alternative health advice has never been more accessible. These self-proclaimed healers are filling a historical void left by institutionalised healthcare services. However, this resurgence of alternative health advice comes with its risks. To answer the question of this essay: Are TikTok Healers Contemporary Quacks or Re-risen Witches*? Well, there is no real answer to it. The line between profiteers and well-intentioned healers is blurry, questionable remedies and supplements gain popularity. Misinformation spreads at an unprecedented pace, often with dangerous consequences; overdoses, unwanted pregnancies, hypochondria, etcetera. TikTok healers have created a complex web of information, misinformation, and confusion. We have started the historical process over, but in this restarting, we are stuck in repeating the same mistakes, the same violence, and causing new harm.

Nonetheless, it's crucial to view TikTok healers not solely as threats but as signals for much-needed change within our healthcare institutions. They expose the gaps in our current medical system, highlighting the need for a more empathetic approach to healthcare, comprehensive education on our bodies, and a reevaluation of herbal remedies that have been neglected for centuries. There has to be a third option. By taking herbalism seriously, conducting rigorous research, and listening to the concerns of women, we can come to a more informed and empathetic approach to healthcare. The persistence of these practices, despite centuries of suppression, underscores their profound importance and efficacy.

One personal question remains then; Am I truly a hypochondriac, or am I simply seeking more understanding of my body - that I’m not receiving from today’s official medical instances?

Notes

1. My use of the asterisk is meant as a way to indicate a difference between historical witches and contemporary witches*. Historically, women were persecuted as witches, a term that was not self-applied, but a label imposed upon these individuals by their persecutors. While re-risen witches* points to women who boldly reclaim this title today as an act of resistance.

2. https://blog.google/technology/health/world-health-organization-google-collaboration-health-information/

3. Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (London: Penguin Books, 2004), 201.

4. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (Cuny: The Feminist Press, 2010), 41.

5. Maya Dusenbery, Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick (New York: HarperCollins, 2018): 25.

6. John M. Riddle, Eve‘s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1999).

7. Item dat oec egheenen cramers oft cruyeniers hen der apotecarie niet verstaene eenige medicinen, laxativen, vomitiven, tyriacle oft wormcruydt, salven oft diergelicke en selen moegen vercoopen, ten ware dat se bijden voers, meesters geexamineert waren. [free translation: market traders may not sell any medicines, laxatives, emetics, theriac, or tansy (back then categorised as artemisia), ointments, or the like that have not been approved by the aforementioned masters, unless they have been examined by them.] SAM, C. Magistraat (Ordonnantiën), S. V, nr. 1, fol. 120r-123v: Stadsordinantie 16 September 1536.

8. Fragment in De Avondshow met Arjen Lubach (VPRO) about natural contraceptives, 27 Sep 2023. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmZJEKhDZxo&t=321s); Dutch Deadline, “The highest abortion rate in 36 years. Blame Tiktok,” 21 Oct 2023.(https://dutchdeadline.substack.com/p/the-highest-abortion-rate-in-36-years?r=bh8nu&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post); BNNVARA, Lisa Schuurmans, “Waarom kiezen steeds meer vrouwen voor natuurlijke anticonceptiemethoden?” 26 Sept 2023. (https://www.bnnvara.nl/artikelen/waarom-kiezen-steeds-meer-vrouwen-voor-natuurlijke-anticonceptiemethoden); De Volkskrant, “Opvallende stijging in aantal abortussen, hoeveelheid op hoogste niveau in 36 jaar,” 12 Oct 2023. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/opvallende-stijging-in-aantal-abortussen-hoeveelheid-op-hoogste-niveau-in-36-jaar~b412230f/?referrer=https://dutchdeadline.substack.com