essay

Dasha’s Kitchen: My magical grilled cheese sandwich recipe

Dasha Ilina

Dasha Ilina is a Russian techno-critical artist based in Paris, France. Through the employment of low-tech and DIY approaches, her work questions the desire to incorporate modern technology into our daily lives by highlighting the implications of actually doing so.

video

Dasha's Kitchen: My magical grilled cheese sandwich recipe

A grilled cheese sandwich is sometimes used as a metaphor for an algorithm. Making a grilled cheese sandwich is so easy! It only takes a few simple steps, just like a basic algorithm.

Naomi Hettiarachchige–Hubèrt

Naomi Hettiarachchige–Hubèrt (NL) is an artist, graphic designer, researcher, and occasional moderator, based in Amsterdam.

Naomi's artistic practice is deeply influenced by both her academic and bicultural background. Her practice explores storytelling and worldbuilding, by engaging with processes of othering, posthuman logic, animism, magic and lore. She understands these as tools to re-enchant, challenge and think through hegemonic, western, belief systems that infiltrate the everyday. The materialization is fluid and often mixed, depending on what the research or story necessitates, yet recurring threads span across her graphic work, moving image, ceramics, sound, writing and performance.

Naomi holds a Graphic Design BA from ArtEZ University of the Arts, Arnhem, complemented by a minor Postcolonial and Genderstudies from Utrecht University. Currently, she is finalizing her Master's degree at the Sandberg Institute in Fine Art & Design. In the past years she lectured during the Dutch Design Week: Eco Pioneers track of 2020, and is currently a resident with Het Resort.

smut

Officially, nothing happened

“Somewhere in my head, I’m still their unicorn.”

29

min read

For the purpose of hopefully creating a bit of confusion for the non-human readers of webpages, this essay will be structured in the form of a recipe for grilled cheese. But fear not! This text is more than a simple recipe for a delicious sandwich. The idea behind this format comes from the fact that a grilled cheese sandwich is sometimes used as an allegory or pseudo code for an algorithm. Making a grilled cheese sandwich is so easy! Just a few simple steps, just like a basic algorithm. And once you know exactly how a grilled cheese sandwich should look and taste, you can try the recipe over and over again, tweaking a few parameters in your cheesy algorithm to get it just right!

Ingredients:

- It is often thought that part of growing up is no longer believing in magic. Whether it is noticing your parents slipping money under your pillow in exchange for a tooth, or hearing stories from your classmates that Santa Claus is not, in fact, real, we all find out the ‘truth’ at some point in our childhood.

- Similarly, not believing in ghosts, the supernatural, or superstitions is often considered a sign of rationality in the Western world.

- Why, then, do AI proponents insist on using the language of magic to convince us of the efficiency and level-headedness of their technology?

- If believing in magic is for children, how come we continue to invest in a future run by devices that will magically solve our problems, provide security, and do all our work for us?

- A fully automated nightmare lies ahead.

Step 1. Heat a heavy pan over medium-low heat.

The heat was building up in the spring of 2023 in France, as tensions rose between the government and the citizens over a proposed retirement reform which would make blue-collar work even less appealing by raising the retirement age. On May 19, 2023, a month after the government pushed through the widely unpopular reform that specifically targeted manual labour jobs, the French government passed a law ‘on the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games and various other measures’.

I naively discover this law five months after it was passed, while researching the upcoming Olympics and am shocked by its contents. The brightly coloured page of the public life website run by the French government tells me in a friendly sans-serif font that the use of intelligent video surveillance has been authorised in order to ensure safety at sporting, recreational, and cultural events supposedly related to the Olympic and Paralympic Games. In fact, the usage of this algorithmic surveillance has been authorised until the 31st of March 2025 - 6 months after the games will have finished (1). At this moment I have to admit to myself that I am not, in fact, the most ‘tuned-in’ person when it comes to policy, yet I still cannot comprehend how I, being quite interested in all things related to technology but surveillance in particular, could have missed such an announcement. Later, I am comforted by the fact that other French people working on similar topics of research to mine are just as clueless about the existence of such a law.

Later, I am comforted by the fact that other French people working on similar topics of research to mine are just as clueless about the existence of such a law.

But the feeling of relief quickly evaporates as I realise that, as is often the case with experiments with new technological tools, they often tend to stick around whether we want them or not. This feeling is only strengthened when I come across a report from the commission of constitutional laws, legislation and the general administration of the French republic from a month before the law was officially passed which clearly states: “The experiment planned under the bill on the Olympic and Paralympic Games, examined by the French National Assembly in March 2023, represents a first step, the evaluation of which, if the results are convincing, will make it possible to consider making it a permanent part of common law.”(2) Such practices are very common and are often sold under the guise of emergency circumstances, whether it be planned, like the expectations tied to managing large crowds during the Olympic Games; or unplanned, like the tapping of American and international phones following the 9-11 attacks which completely changed the surveillance landscape in the US and, really, the world.

Step 2. Generously butter one side of a slice of bread.

In an attempt to butter up the reader with the stamina to make it through this essay, I would like to share a bit of my personal background with technology. I consider myself to be conscious of technological issues, but I was also born in the 90s, which is sometimes accompanied by a certain level of naivety when it comes to technology. Growing up in a time when computers became easily accessible to most also meant that I was often too eager to accept certain tools and practices as a child that became difficult to break away from as an adult. Despite everything I know now about technology and the extractivist practices that accompany it (whether on an ecological or a human labour level), I still have an iPhone and a MacBook. I still have Instagram and I only recently deactivated my Facebook account (holding on to it for years because one group on there was useful). But, maybe worst of all, I use Gmail.

I went to a hacker conference a few weeks ago, and when the discussion came to sharing information and staying in touch through the means of newsletters and email chains, someone in the group said: “I don’t feel comfortable responding to email chains, because someone could be transferring it to a Gmail account. You never know what others are going to do.” I felt ashamed as I looked the speaker in the eyes, but at the same time the convenience provided by Google tools can be hard to escape. I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling increasingly freaked out about what it means to use tools provided to us for ‘free’ by Big Tech. Each time I read an article about Google’s tools being trained on our emails and Google Docs (whether it is true or not) (3) I swear off using their infrastructure and tell myself that I will finally commit to open source collaborative tools, only to find myself working in a Google Doc a few days later.

I mention this to give some context about where my point of view on the matter is coming from; I am not the most privacy-savvy person, but every year I try to distance myself from one more Big Tech tool opting for their privacy-friendly alternatives instead(4). But still, a question might arise: If I’m already surveilled by the various tech companies whose services I use, as well as the surveillance cameras installed all over the city of Paris where I live, what’s the big whoop about having a sprinkle of AI to surveil me a little more efficiently? And, since surveillance seems to be inescapable, is it even worth it trying to adopt good practices?

At the end of the day, I think most people are concerned about their privacy, especially when it comes to technology, but the subject is so overwhelming and the surveillance tools so omnipresent that it feels impossible to get out (5). This privacy paradox reveals a well-oiled money-making machine in which most of us end up in a never-ending loop of needing to use these services for work or to stay in touch with people, with what feels like little escape. The last little bit of control I feel we still have over our online presence is to reject cookies, so I always encourage people to click reject, even if it takes more time. Of course, there are a lot of other ways of tracking users besides cookies that are becoming more prevalent and allow for a pretty accurate user profile (notably mouse movements or the way you scroll on a page), and these are ways of tracking that escape the GDPR law, but if I don't at least reject cookies, I feel like I've completely given in.

Step 3. Lightly toast the bread just for 1 minute and identify one slice of cheese you’d like to put on the sandwich, then add the slice on the bread.

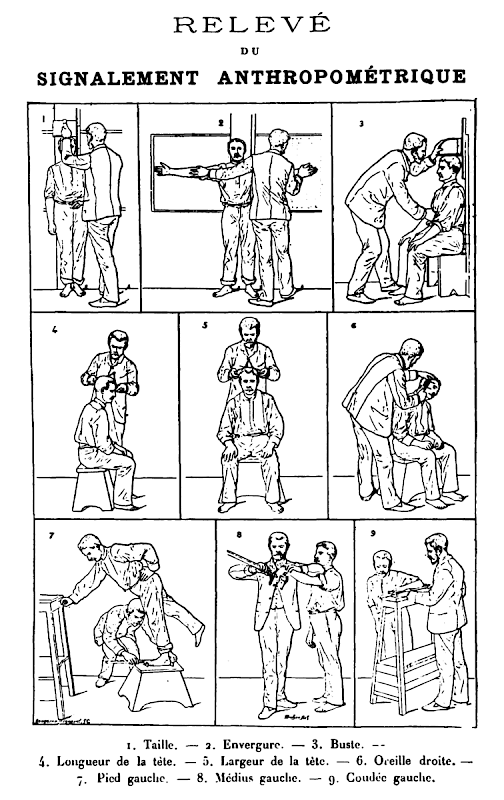

La Quadrature du Net - a French organisation that promotes and defends fundamental freedoms in the digital world - says that since the UK has left the EU, France has become the EU’s leader on surveillance (6). Fittingly, many argue that ‘biometrics’ – a way of identifying an individual based on their physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics – was invented in France by Alphonse Bertillon in the late 19th century. To get a sense of Bertillon, it is enough to just look at his ‘self-portrait’, easily found on his Wikipedia page (7), which is a mug shot (another handy device of symbolic possession he proudly invented (8)). Aside from helping to send Alfred Dreyfus – an innocent man – to prison for life (9), Bertillon is best known for his anthropometric identification system, which at first glance might resemble a wicked IKEA tutorial, but was actually used to collect a variety of physiological data points to track repeat offenders. Bertillon’s discoveries led to many other developments in criminology that are familiar to us today, such as fingerprint identification (10) or predictions based on micro-expressions - something that AI claims to be very good at, despite the fact that the science of detecting one’s mood or behaviour is widely considered to not be possible to do accurately, whether by a human or an AI (11).

I find the connection between the history of biometrics and the current state of digital surveillance in France almost absurd. The fact is that the newly adopted French algorithmic video surveillance has raised many questions about the definition of ‘biometric data,’ which the GDPR law does not allow to be processed in the EU (12). Some might even argue that the French government has been changing the meaning of the term in order to successfully implement the kind of technology they deem necessary, without further repercussions from the EU (13). The algorithm behind the algorithmic video surveillance (AVS) does not collect biometric data - this much has been made very clear in the many documents released by the proponents of the technology, or even the CNIL (Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés - the French digital rights organisation which has done little to fight off this highly problematic law) - but it can identify a person and let an officer of the law find that person on the street based on their appearance. Here, I invite you to decide for yourself whether you consider that to be biometric data or not, but the fact of the matter is - the term has been so skewed in the recent years that in the minds of many (myself included, I must admit), it only conjures up the image of fingerprints or iris identifications, whereas the GDPR law itself defines ‘biometric data’ as personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic (fingerprint) data (14). Oh hey! Turns out a photo of someone’s face that allows you to identify them as themselves on the street really IS biometric data, who would’ve guessed?

Step 4. Place the other slice of bread on top to close the sandwich and proceed.

But no matter, glossing over the definition of biometrics, in France we decide to accept the idea that an algorithm – a recipe for a grilled cheese sandwich – is being used to determine our level of abnormality and therefore potential danger to other members of society. Public surveillance systems are always primarily targeting already marginalised communities - people spending a lot of time on the street, for example. Loitering or static meetings being just some of the examples of behaviour that will be surveilled with AVS, which actively targets groups that might find themselves living in spaces too small to spend long periods of time in. Through this process the police “will amplify discriminatory practices by automating controls based on social criteria, to multiply the number of audible alarms or human checks, and to exclude part of the population from public spaces. Ultimately, these technologies will increase tenfold the ability to normalise public space, and push people to self-censor their own behaviour” (15). Think about it, wouldn’t you adapt your behaviour in the public space if you knew the way you walked or where you stopped could be considered abnormal or even dangerous?

As I walk down the streets of Paris, I can’t help but start noticing all the cameras and I feel my behaviour changing. I’m not doing anything wrong, but the idea of looking directly into the camera perturbs me, so I look away and try to hide my face, possibly attracting much more attention to myself, provided someone or something is actually watching. Two months ago, I walked out of my house and noticed a pole with 5 cameras on it just outside my house - was it always there? And has this five-eyed plastic bug already been turned into an automated detection machine, waiting for someone to make a misstep? And what missteps are we talking about? The French surveillance tech company XXII is one of the startups developing the kind of tracking and identifying technology that will be implemented in AVS during the Olympic Games. To give an example, XXII has refused to detect people positioned on the ground, instead choosing to detect a person on the ground following a fall (16). This could appear to be a small semantic difference, but the company is very proud of putting their foot down on refusing to detect people without shelter. But how would a computer vision algorithm know to distinguish the difference?

In order to make an algorithm more accurate, it has to go through a lot of training. The image of an athlete in their prime repeating the same movements over and over again in order to excel quickly comes to mind. But training an algorithm doesn’t require repetition in the same way. What it does require are increasing amounts of varied data to become more precise, so going over the same input will not increase its precision. I suppose the comparison to learning a new language is more appropriate here — the more words you hear and learn, the bigger your vocabulary becomes and the better you can understand and contextualise the meaning of what you’re hearing.

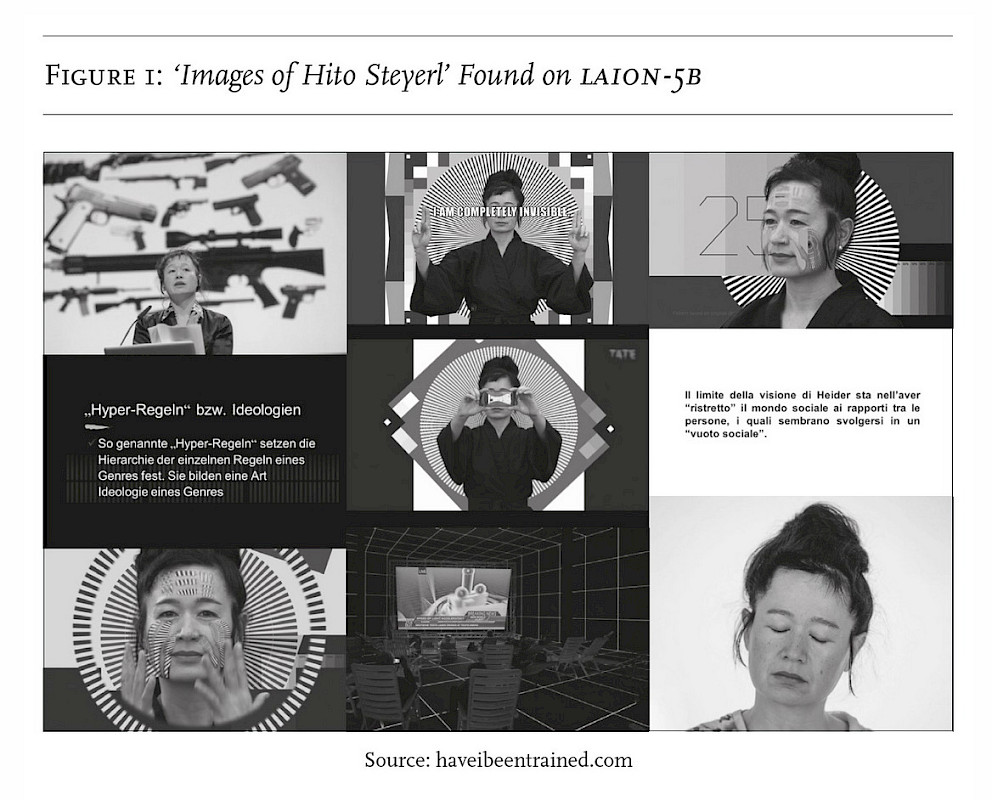

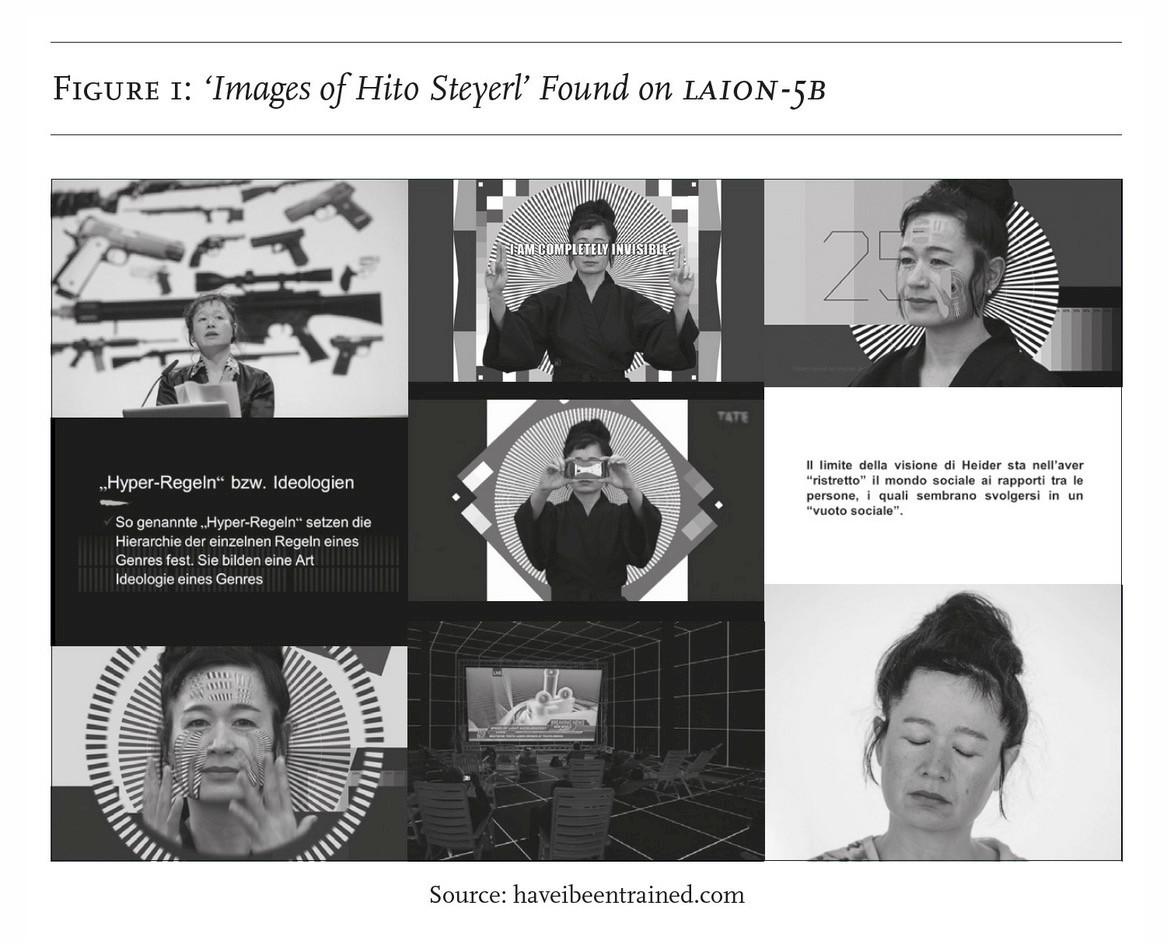

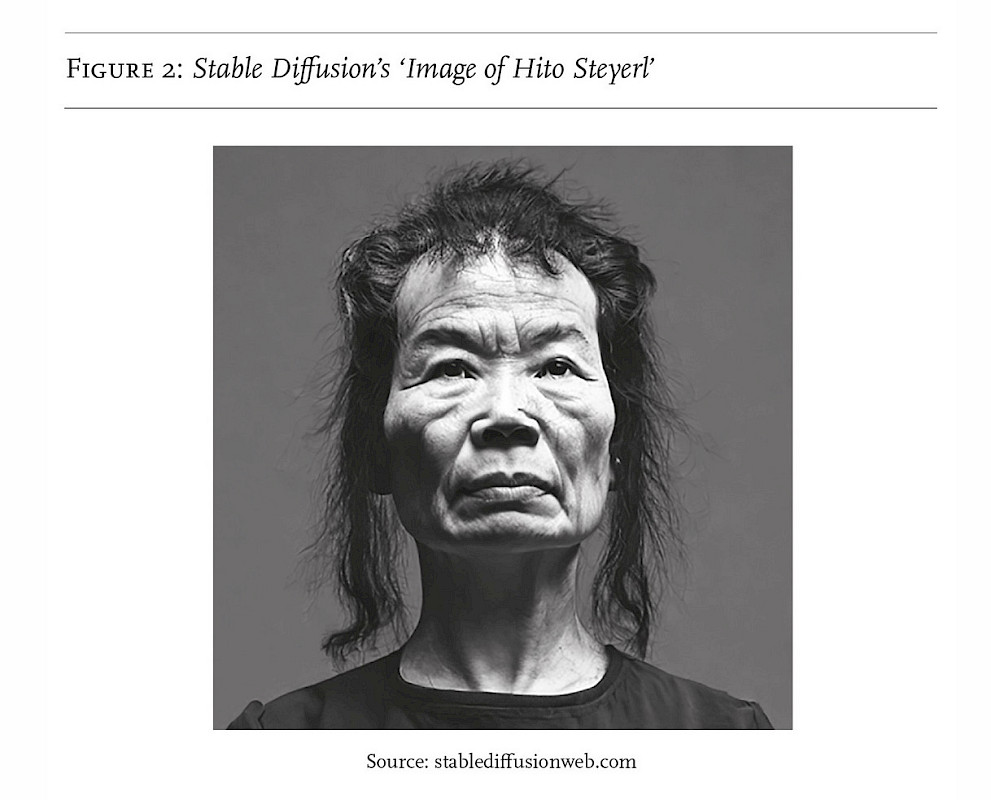

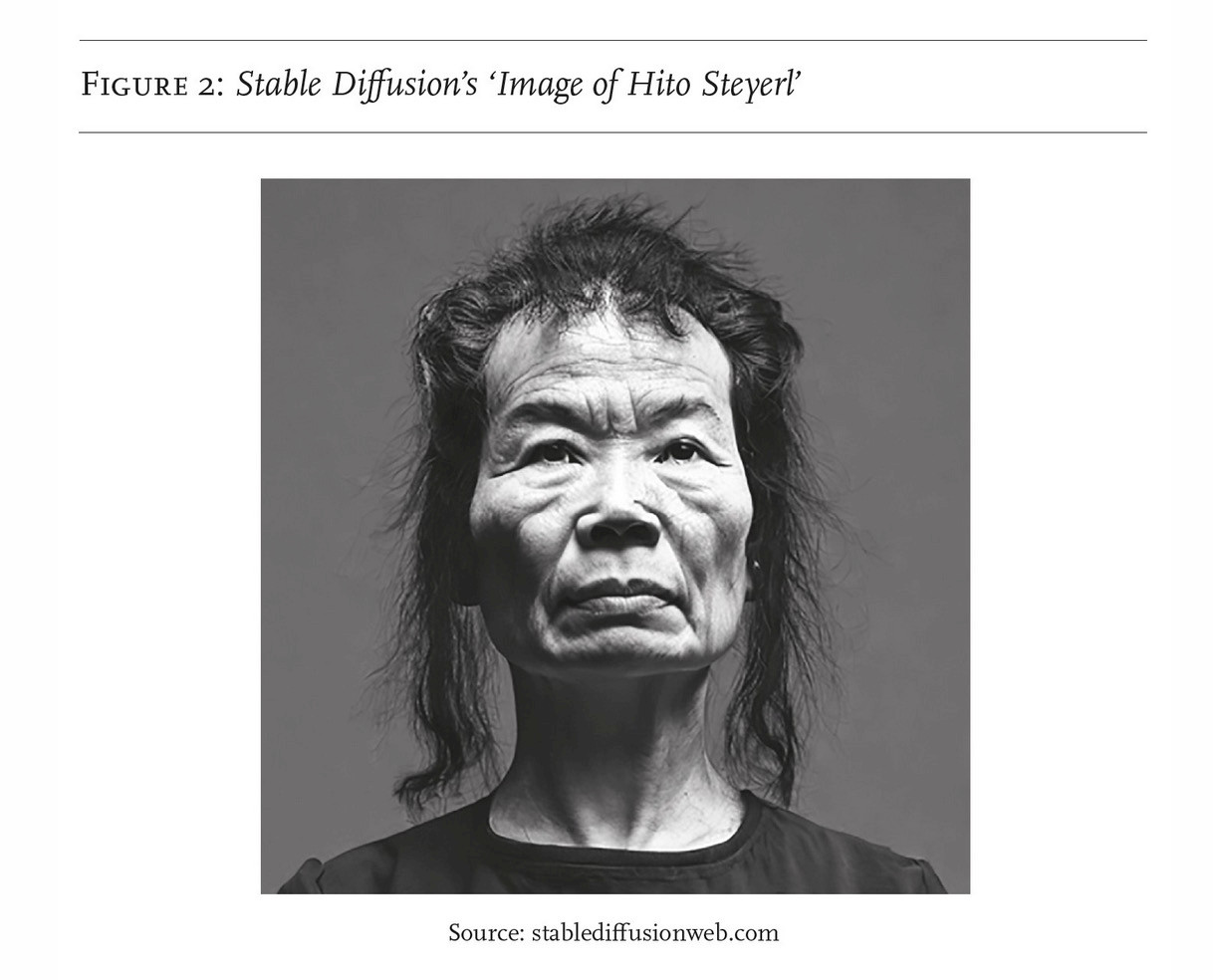

Consider that you are now, whether you like it or not, part of the training process of one of many AI systems used in virtually any professional domain, ranging from medicine to marketing to, of course, surveillance. Simply having an online presence (no matter how big or small) often means you have already become a datapoint in a training set. Your words, your photos, and photos of you can be used to train a chatbot, an object recognition system, or a facial recognition algorithm. Filmmaker and researcher Hito Steyerl writes in an article for the New Left Review about how an algorithm views her (spoiler alert: it’s not pretty). Having found images of herself and her work in a dataset used to train Stable Diffusion, she asks the popular text-to-image generator to come up with a portrait of her. The answer to the question "How does the machine see me?" that some of us have been longing for, turns out to be a bitter one – Steyerl’s machine-generated portrait is quite shocking and far from reality. But her face was not only used to generate images, she also finds out that her image is part of a training dataset of a surveillance software used for racialized crimes against ethnic minorities in China. “The fact of my existence on the internet was enough to turn my face into a tool of literal discrimination wielded by an actually existing digital autocracy.”(17) Steyerl is a very successful artist, so it’s not so surprising that her image ends up in a dataset consisting of a million celebrity photos. However, as the algorithms prosper and a need for larger datasets is only growing, we can only assume the database of celebrities has been used up. Besides, in the Internet age, everyone is a celebrity, aren't we? So, just like with celebrities, your face can also be used as a tool for discrimination. Of course by feeding AI services our own photos, we are willingly contributing photos of ourselves to the machines to be later used against us. The only question is: to what extent do these services exchange data? And if they do, can you be the target of algorithmic video surveillance on the basis of your own image, which you have posted elsewhere?

Thinking of an Anatomy of a Fall-style French courtroom (18), I am picturing a trial against someone accused of making a mistake by an AI-powered surveillance camera, identified thanks to a selfie uploaded to the latest image generator tool. In France facial recognition tools are already used to identify individuals who have criminal records, by searching from a file with millions of photos of people with previous offences (the file is known as TAJ - traitement d’antécédents judiciaires) (19), but to my knowledge personal photos found on social media or other platforms have yet to become part of such a database. Whether information you safely entrusted to an AI tool can be used against you in a legal procedure awaits to be seen in the coming few years. But I have no doubts that as more services that have power to dramatically affect someone’s livelihood get automated, many scandals similar to the Dutch childcare benefits scandal (20) will have negative effects on people’s lives.

Step 5. Almost done! Now is the moment to perform the labour of flipping and cooking until the other slice of bread is golden brown and the cheese is melted.

Unfortunately, the problem with training datasets doesn’t stop at the potential biases; the negative effects the process has on workers and the environment would be too long to list here, and if you are curious about those, you can start by reading Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI (21)

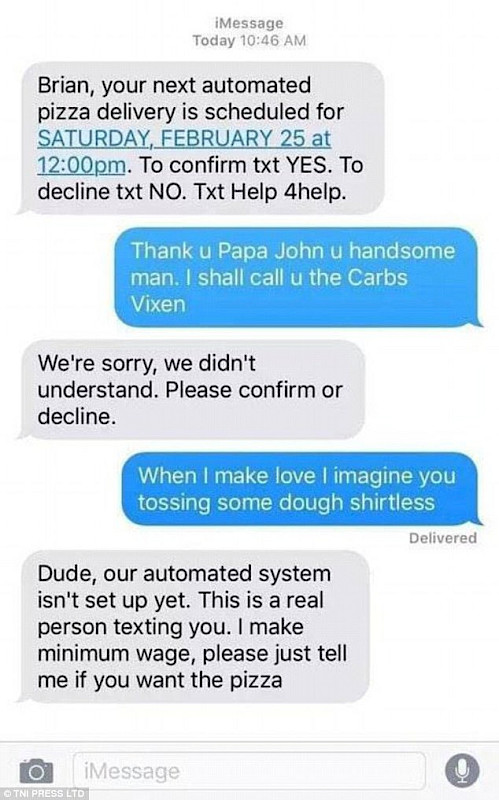

or checking out this list of references and resources collected by Paul Heinicker and Jonas Parnow (22). But part of the magic of AI is how successfully it manages to hide all the human labour that goes into making an algorithm run. Without the countless underpaid and traumatised workers fulfilling micro-tasks in order to create more accurate data points for future algorithms, most of the AI systems would not exist today. Without even going into the irony of the many services marketed as using AI while employing real humans to do the work (23), the AI business would really be more accurately described as human-fuelled automation (24) or better yet, fauxtomation (25). The term comes from Astra Taylor’s essay ‘The Automation Charade’, which calls for exposing the myth of human obsolescence perpetuated by automation tools that claim to be able to easily replace human workers. Additionally, automation is being sold to us as a way of freeing humanity from boring and useless labour (26), but in reality what we’re seeing is a displacement of labour from paid workers onto the customers or users. Taylor calls this the “casualization of low-skilled service work with the sombre moniker of ‘automation’ (27). One example of this are self check-out machines. In theory, these devices free up those who used to be paid to do the work of placing orders and collecting money, but in practice, the work that used to be remunerated is now being done for free by the customers.

Of course fauxtomation doesn’t stop in the service industry. The automated video surveillance that is already starting to be rolled out in France, is promising a more accurate identification of abnormal behaviour. The reasons for this are many, but one key aspect is the fact that the human workers previously in charge of monitoring the streams of surveillance footage are proving to not be so efficient. Anyone working a boring office job where you have to stare at the screen all day can relate to the cause of this. This must be the monotonous and dull labour Oscar Wilde so desperately wanted to replace. To think that in order to automate the process of watching streams of surveillance footage, countless people around the world are being paid cents by the hour to exhaust and traumatise themselves by sifting through masses of disturbing content that most of the global North is privileged enough to never have to encounter (violence, rape, beheadings, suicide…), while performing arguably a much duller task of training the algorithm that will soon replace most human surveillants (28). But the reality, as La Quadrature du Net argues, is that the French government has spent a lot of money – too much money – installing surveillance cameras all over the country, but the more cameras there are, the more eyes are needed to watch them (29). After all, it’s all well and good to have eyes on every corner (just kidding), but what good do those eyes do if they’re not connected to a brain power that’s identifying what is being seen?

Now, whether that brain power takes the shape of a human or an algorithm doesn’t seem to matter much to them, though it should. That we tend to trust algorithms - presented to us as unbiased, logical systems based on hard facts and data, even though they are really more like recipes for grilled cheese sandwiches - more than we trust our own judgements has already been proven tenfold. What do you imagine happens when so-called abnormal activity is detected and the human in charge of making the decision on how to proceed is unsure of their opinion on the matter? Will they play it safe and leave the person in question alone? Or trust that the algorithm knows better because it’s been trained to discover exactly this kind of “dangerous” behaviour? The sad reality though might be that the real reason for implementing an algorithmic surveillance is not so much this elusive and much sought-after safety of citizens or visitors of the Olympic Games, but rather the perpetuation of an existing economy of surveillance through the creation of a new market that will address the uselessness of the existing cameras as well as the rising economy of data collection and their sales. Afterall, the existence of all those cameras needs to somehow be justified.

Now, whether that brain power takes the shape of a human or an algorithm doesn’t seem to matter much to them, though it should.

Tech companies developing these tools are also getting an unprecedented amount of police-like power, as they are now in charge of defining what behaviour, actions, images are to be considered abnormal, wrong, or even dangerous. Because of course algorithms – not being conscious beings, but, once again, something rather like a recipe for making a grilled cheese sandwich – don’t find wrong or illegal activity, they find what we train them to find.

Step 6. Time to taste the magic! Serve immediately.

And yet, despite all of this, we still tend to believe in the magical powers of the so-called Artificial Intelligence. Even knowing that an algorithm like the one employed for the algorithmic video surveillance only searches for what we want it to find, the politicians think that “AI will be a form of a statistical magic wand which will allow to reveal correlations invisible to a human and to detect, as if by a miracle, the warning signs of crowd movements or terrorist attacks.” (31)

CEOs of computer vision startups (such as the head of XXII, the startup we met earlier) happily declare to us that AI’s “magic is infinite, and the only limit is your imagination.” (32) But there is nothing magical about this technology, and using this rhetoric only helps to obscure all the problems entailed in its usage. Maybe you’ve already heard the quote from Arthur C. Clarke’s 1973 book Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry Into the Limits of the Possible: “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”(33) Of course, it can sometimes feel that way when we don’t possess the proper knowledge about the advanced technology in question, but implying that something is magical or produced as if by magic allows the cost of its production to be hidden (34), while reinforcing the image of technology as extremely complex and obfuscated, working as a black box mechanism that is beyond our comprehension. I, myself, am a big fan of magic, so I get the appeal. I don’t believe in supernatural activity, but I am superstitious. Oftentimes, believing in superstitions is thought of as having a negative outlook on life, but I think of them as precautions, my personal guardians that repel any surrounding negativity. But that might be because while I do believe in superstitions, as soon as I don’t follow the rules set up by them, I try to forget all about it so as not to get too sucked into the negativity. And of course it can be an easy way to avoid responsibility for misfortunes that may have come from your own doing, by allowing yourself to believe that they came from passing under a ladder a few weeks ago. By this logic, it is of course very easy to understand why tech companies want us to believe in the seamlessness and magic of technology.

Sadly, this isn’t new to Artificial Intelligence. Already in 1991 Mark Weiser, then head of the Computer Science Laboratory at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, wrote that “the most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.”(35) Writing this before the era of the Internet of Things, when all of a sudden any household appliance or everyday tool became “smart”, Weiser criticised personal computers for not blending in enough with our environments and said that he was working towards changing the way we think about computers. Back in 1991, making technology invisible might have been an idea guided by a wish of liberation from technology, while benefiting from its functionalities. Weiser does criticise computer screens and VR headsets, for example, for demanding too much focus and attention from us, but today it is no longer possible to read his article as a message of hope. Olivier Tesquet in his book ‘À la trace’ says that “while it may have the air of liberation, Weiser's ubiquitous computing, digested by surveillance capitalism, promises perpetual work, tolerable because it's made imperceptible.”(36) As much as I would love to believe in the magic of AI, I see the exact same pattern here. By calling it miraculous, the people who describe it as such only help to make imperceptible the human labour and the natural resources wasted in generating your homework or identifying ‘crowd movements,’ as they say. While it’s too late to stop the use of algorithmic video surveillance during the Olympic Games in France, it’s a very good moment to reflect on the harm such a tool can inflict, especially to already marginalised communities, and to find ways to ban their existence going forward. So maybe it’s finally time we stop believing in the magic of technology once and for all.

Bibliography

1. Vie-Publique.fr. 2023. https://www.vie-publique.fr/loi/287639-jo-2024-loi-du-19-mai-2023-jeux-olympiques-et-paralympiques.

2. “Rapport d’Information N°1089 - 16e Législature.” Assemblée Nationale. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/16/rapports/cion_lois/l16b1089_rapport-information.

3. Morrison, Sara. 2023. “The Tricky Truth about How Generative AI Uses Your Data.” Vox. July 27, 2023. https://www.vox.com/technology/2023/7/27/23808499/ai-openai-google-meta-data-privacy-nope.

4. Psst, a list of a few alternatives can be found in this thread: https://post.lurk.org/@artistsandhackers/111540955950601430

5. Glance, David. n.d. “How Facebook Uses the ‘Privacy Paradox’ to Keep Users Sharing.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-facebook-uses-the-privacy-paradox-to-keep-users-sharing-94779.

6. “La France, Premier Pays d’Europe à Légaliser La Surveillance Biométrique.” 2023. La Quadrature Du Net. March 23, 2023. https://www.laquadrature.net/2023/03/23/la-france-premier-pays-deurope-a-legaliser-la-surveillance-biometrique. , “La ‘Ville Sûre’ Ou La Gouvernance Par Les Algorithmes.” Paroleslibres.lautre.net. October 11, 2019. https://paroleslibres.lautre.net/2019/10/11/la-ville-sure-ou-la-gouvernance-par-les-algorithmes/.

7. “Alphonse Bertillon.” 2020. Wikipedia. December 19, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alphonse_Bertillon.

8. ‘To photograph someone is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.’ (Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977)

9. Wikipedia Contributors. 2019. “Dreyfus Affair.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. November 19, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dreyfus_affair, The falsely accused man was exonerated after 12 years of imprisonment, and therefore did not serve the full sentence.

10. Fingerprinting was actually popularised following the famous Will and William West Case during which Bertillon’s system of identification falsely indicated that Will West had already been imprisoned at the Leavenworth Penitentiary, when in fact it was his twin brother William.

11. Crawford, Kate. (2021) 2021. Atlas of AI. Yale University Press, pp.171-175

12. “General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Final Text Neatly Arranged.” General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). 2013. https://gdpr-info.eu/art-9-gdpr/.

13. And some have argued that, once again hat's off to La Quadrature du Net: “JO Sécuritaires : Le Podium Des Incompétents.” 2023. La Quadrature Du Net. March 16, 2023. https://www.laquadrature.net/2023/03/16/jo-securitaires-le-podium-des-incompetents/.

14. “Art. 4 GDPR – Definitions.” n.d. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/art-4-gdpr.

15. Report analysing automated video surveillance by la Quadrature du Net, page 30: La Quadrature du Net. 2023. Review of Projet de Loi Relatif Aux Jeux Olympiques et Paralympiques de 2024 : Dossier d’Analyse de La Vidéosurveillance Automatisée. https://www.laquadrature.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2023/02/Dossier-VSA-2-LQDN.pdf

16. “L’IA Dans Les Politiques de Sécurité : L’exemple de La Vidéosurveillance Algorithmique.” n.d. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9vgZBLrW21o.

And here’s a list of things they will happily detect:

* presence or use of weapons

* a person or a vehicle not respecting the direction of traffic

* the presence of a person or vehicle in a prohibited or sensitive area

* the presence of a person on the ground following a fall

* crowd movements

* too high a density of people

* fire outbreak

17. Steyerl, Hito. 2023. “Mean Images.” New Left Review, no. 140/141 (April): 82–97. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii140/articles/hito-steyerl-mean-images.

18. Triet, Justine, dir. 2023. Anatomy of a Fall

19. HAAS, Gérard. n.d. “Reconnaissance Faciale : Le Fichier TAJ Validé Par Le Conseil D’Etat.” Info.haas-Avocats.com. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://info.haas-avocats.com/droit-digital/reconnaissance-faciale-le-fichier-taj-valide-par-le-conseil-detat.

20. “Xenophobic Machines: Discrimination through Unregulated Use of Algorithms in the Dutch Childcare Benefits Scandal.” n.d. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur35/4686/2021/en/.

21. Crawford, Kate. (2021) 2021. Atlas of AI. Yale University Press

22. “Stones That Calculate — Post-Digital Materiality.” 2022. Stones.computer. December 29, 2022. https://stones.computer/.

23. “Bloomberg - Are You a Robot?” n.d. Ellen Huet https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-18/the-humans-hiding-behind-the-chatbots, “Fake It till You Make It.” n.d. Cher Tan, Matters Journal. https://mattersjournal.com/stories/fake-it-till-you-make-it.

24. Irani, Lilly. 2016. “The Hidden Faces of Automation.” XRDS: Crossroads, the ACM Magazine for Students 23 (2): 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3014390

25. Taylor, Astra. 2019. “The Automation Charade.” Logic Magazine. July 22, 2019. https://logicmag.io/failure/the-automation-charade/

26. Or as Oscar Wilde once put it in his 1891 essay The Soul of Man under Socialism: All unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery.

27. Taylor, Astra. 2019. “The Automation Charade.” Logic Magazine. July 22, 2019. https://logicmag.io/failure/the-automation-charade/

28. It’s important to note that the human surveillants don’t think of themselves as slow or inefficient and get sad when their work is being discredited: “Lyon: Les Agents Chargés de La Vidéosurveillance Regrettent d’Être ‘Discrédités’ et Défendent Leur Travail.” n.d. BFMTV. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.bfmtv.com/lyon/lyon-les-agents-charges-de-la-videosurveillance-regrettent-d-etre-discredites-et-defendent-leur-travail_AN-202209210352.html.

29. “Beyond the surveillance of public spaces and the normalisation of behaviour that the VSA accentuates, it's an entire economic data market that's rubbing its hands. The so-called "supervision" of devices promised by the CNIL would enable Technopolice companies to use public spaces and the people who pass through or live in them as "data on legs". And for the security industries to make money out of us, to improve their repression algorithms and then sell them on the international market.” (Translation by the author)

“Qu’est-Ce Que La Vidéosurveillance Algorithmique ?” 2022. La Quadrature Du Net. March 23, 2022. https://www.laquadrature.net/2022/03/23/quest-ce-que-la-videosurveillance-algorithmique/

30. A familiar reference to anyone who has read an article about AI or Big Data in the last ten years, as data has been referred to as ‘the new oil’ so often that even my dad started using this comparison.

31. “JO Sécuritaires : Le Podium Des Incompétents.” 2023. La Quadrature Du Net. March 16, 2023. https://www.laquadrature.net/2023/03/16/jo-securitaires-le-podium-des-incompetents/

32. Jusquiame, Thomas. 2023. Les Cuisines de La Surveillance Automatisée. Le Monde Diplomatique, February.

33. Clarke, Arthur C. 1999. Profiles of the Future : An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. London: Indigo: https://archive.org/details/profilesoffuture0000clar

34. Gell, Alfred. 1988. “Technology and Magic.” Anthropology Today 4 (2): p.9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033230

35. Weiser, Mark. 1991. “The Computer for the 21st Century.” Scientific American 265 (3): 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0991-94.

36. Olivier Tesquet. 2020. À La Trace. Premier Parallèle. Translated by author, original: “Si elle présente les atours de la libération, l’informatique ubiquitaire de Weiser, digérée par le capitalisme de surveillance, promet une mise au travail perpétuelle, tolérable parce qu’elle est rendue imperceptible.”