The Estonian biologist Jakob von Uexküll proposed the idea that every living being lives in its own unique world. He called this world the "Umwelt", introducing the word in his 1909 book Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere.

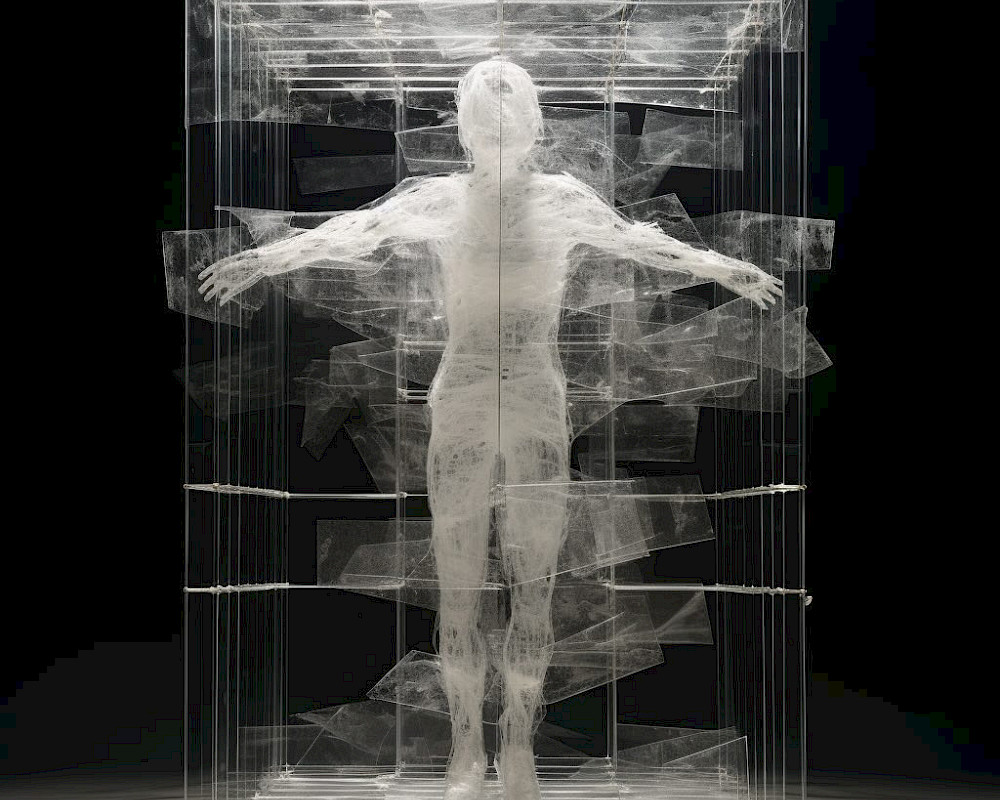

According to Uexküll, the Umwelt is "the world each living being experiences through its own senses and body." We humans perceive and act upon the world through our five senses. Uexküll referred to such beings as "subjects." However, this subjectivity is not limited to humans. Animals in the forest and insects flying through the air each live within their own worlds, shaped by senses entirely different from ours.

For example, Uexküll observed bees reacting surprisingly to simple shapes drawn on paper placed in a garden. They would only land on "open shapes" such as stars or crosses, never on "closed shapes" like circles or squares. Bees do not recognize flowers as humans do. Rather, they navigate the world by detecting simple geometric openings, not by the color or fragrance of the flower. It is through these shape cues alone that they fly and locate nectar.

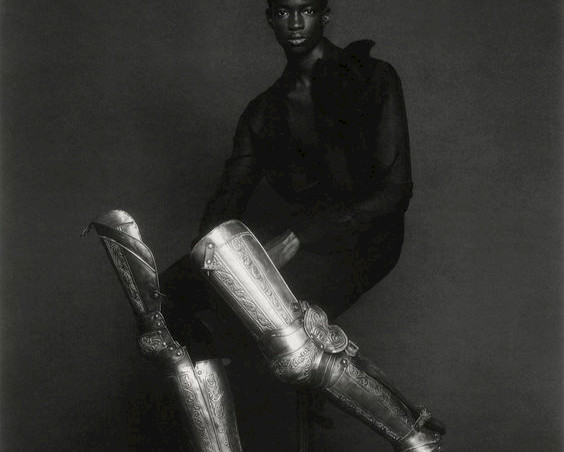

What is essential about the concept of Umwelt is that it is not just about perception but also inseparably tied to action. The "perceptual world" constructed through sensory organs and the "effector world" where the being interacts with its surroundings are constantly influencing each other, forming the Umwelt. The world we live in every day is not simply received passively, but is actively created through the interaction between input and output.

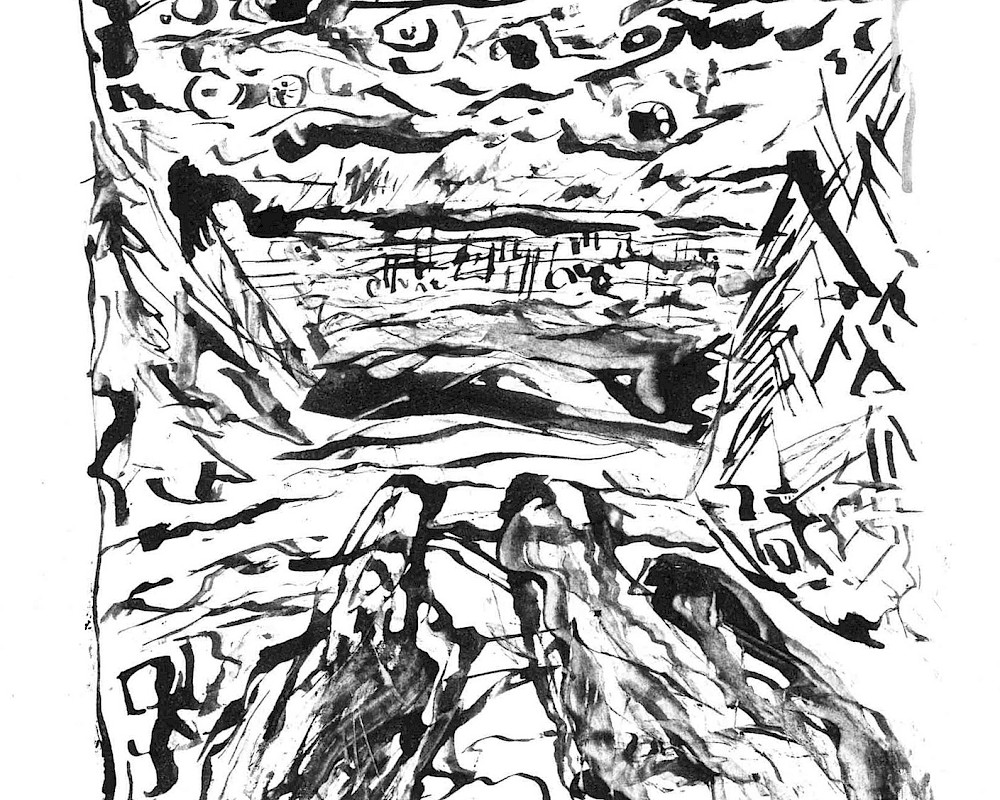

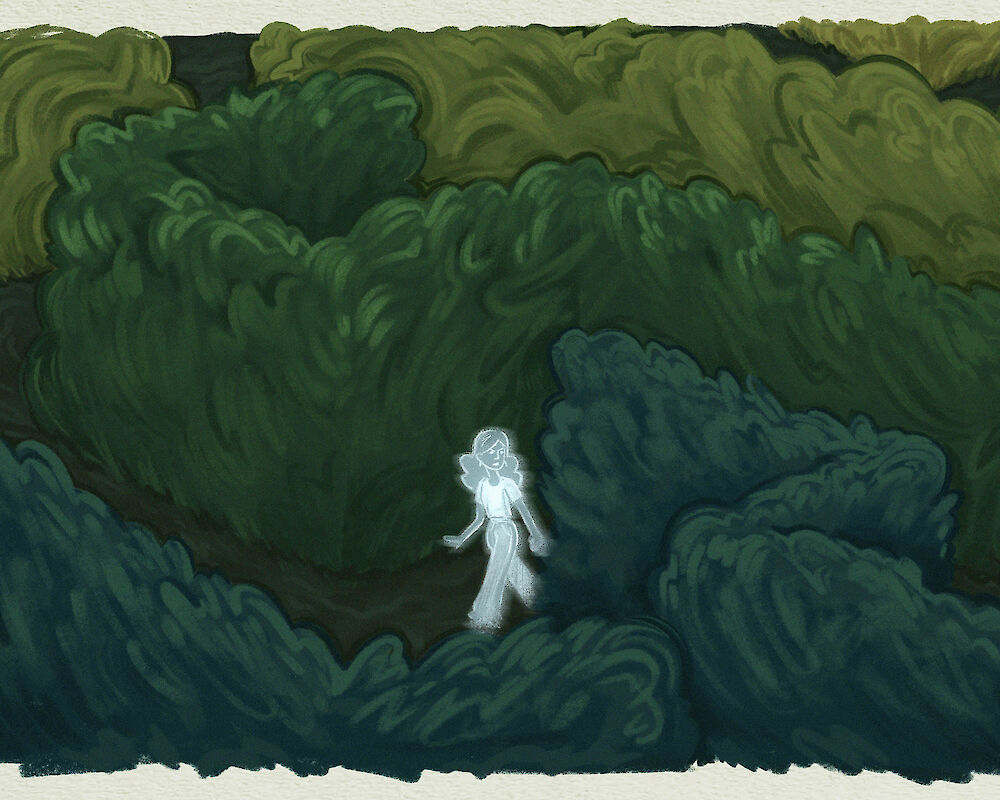

This concept of the Umwelt can be applied to today's internet society. Highly customized social networking services and search engines present different information depending on language, region, and individual preferences. News apps also adjust the content and framing of articles according to the user’s country or political beliefs. Unknowingly, we end up living within a "closed garden" of information, optimally tailored to each of us.

Moreover, these algorithmically crafted informational gardens are more than just convenient features. They are personal secret gardens, accumulating countless fragments that gradually shape our personalities, beliefs, and even our very sense of self. We are, without realizing it, assembling our own identities every day through the fragments of information provided by algorithms.

***

This piece is a contribution to the digital zine “Imaginary Gardens”, produced by the 1st-year Contextual Design masters students at Design Academy Eindhoven, May 2025