9

min read

Sospesi tra cielo e terra, dove il vento sussurra segreti dimenticati,

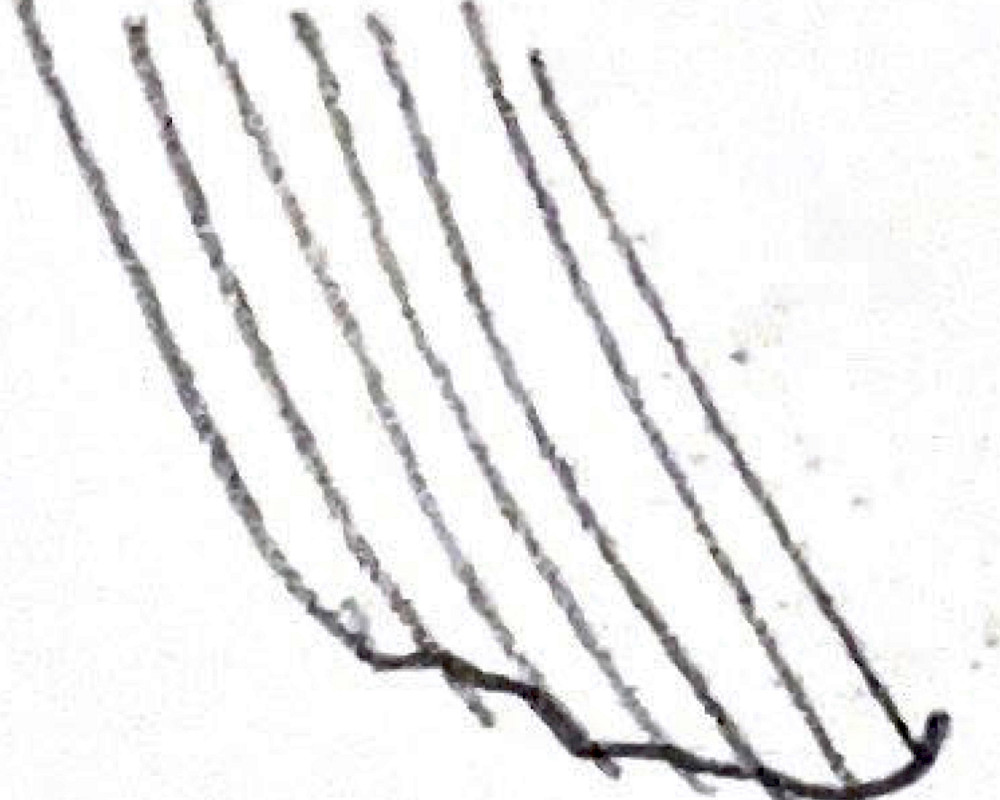

sottili fiori bianchi si aggrappano ai pendii montani con una grazia silenziosa.

Ricami di neve su un trono austero

Nessun passo ne calpesta le radici, nessun desiderio li strappa alla solitudine.

Là dove pochi osano arrivare, i petali sfiorano il vuoto e resistono all’assottigliarsi della terra in cui affondano le sue radici.

***

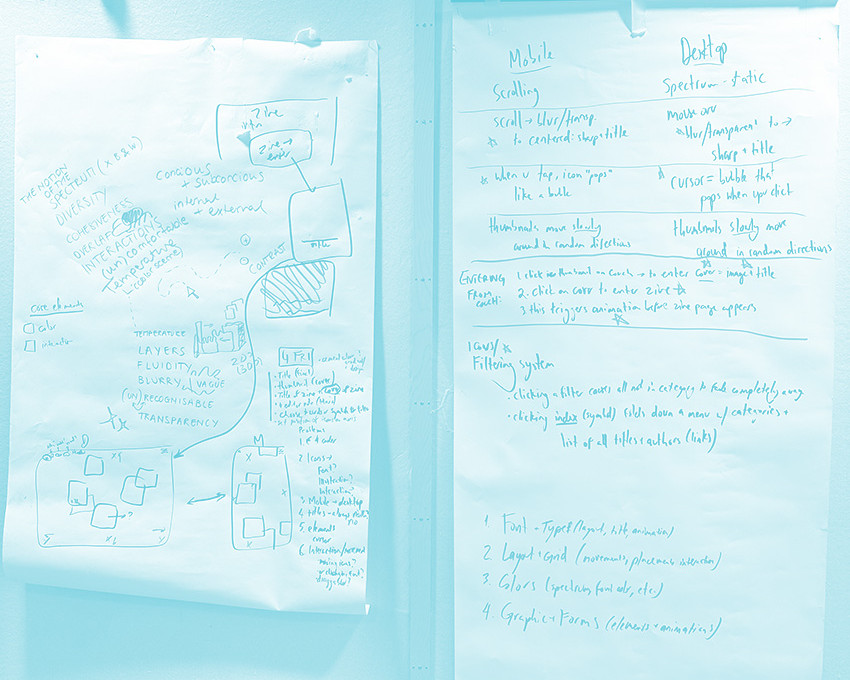

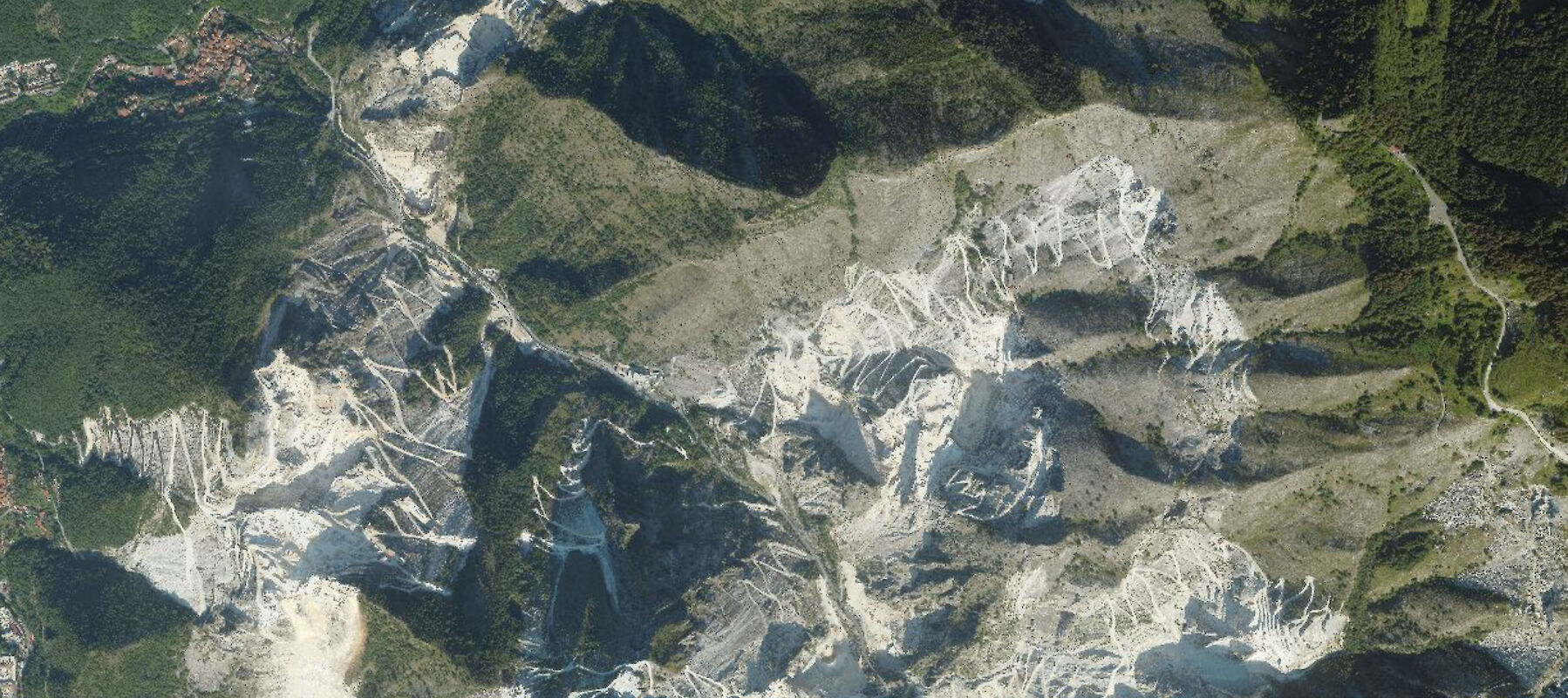

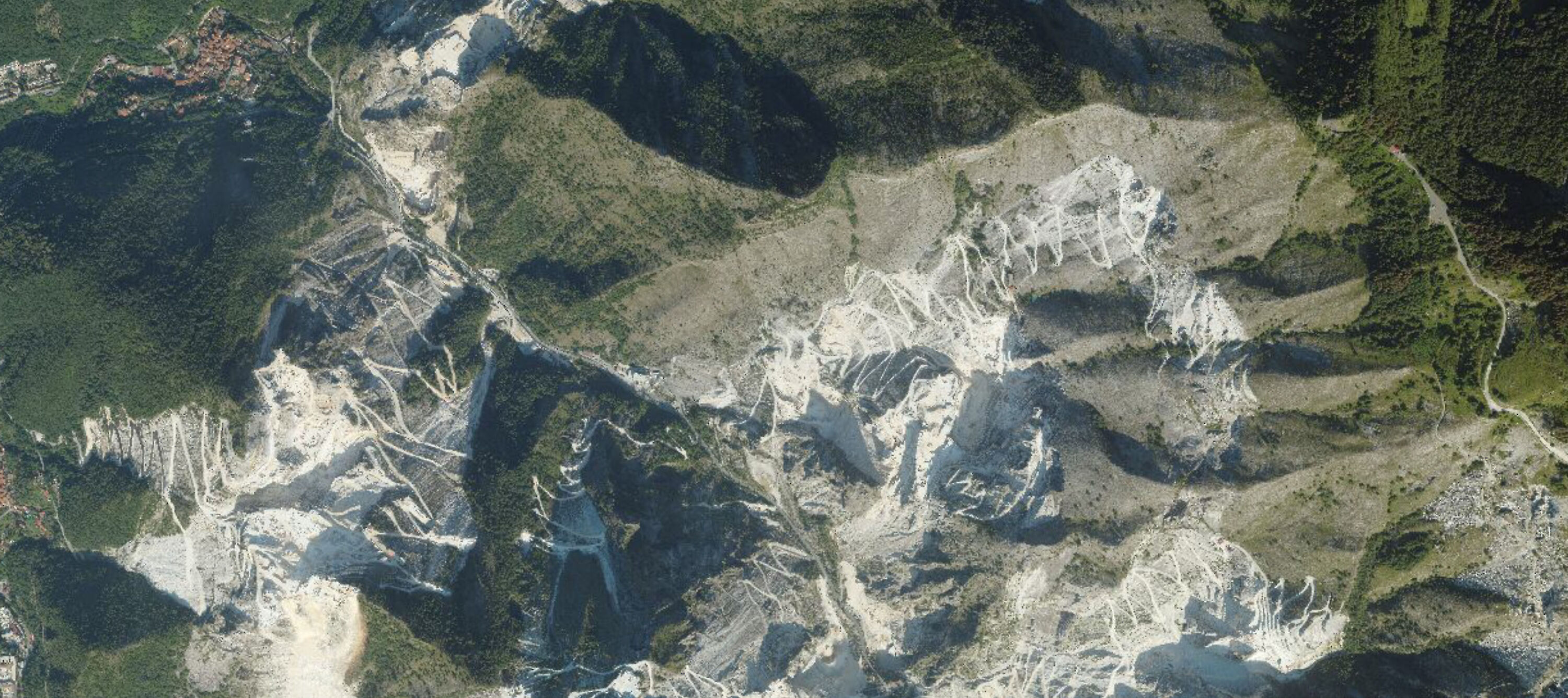

The Apuan Alps are a stark and magnificent landscape - limestone peaks, dense forests, and hidden valleys that have been shaped for centuries by human activity, primarily through marble extraction. This marble, one of the finest in the world, has drawn countless quarrying operations to the region, carving into the land and stripping it of its resources. Over time, the balance between nature and industry has tipped perilously toward destruction, with entire ecosystems lost or threatened. Within this context, Athamanta cortiana grows like a delicate whisper amid the stone.

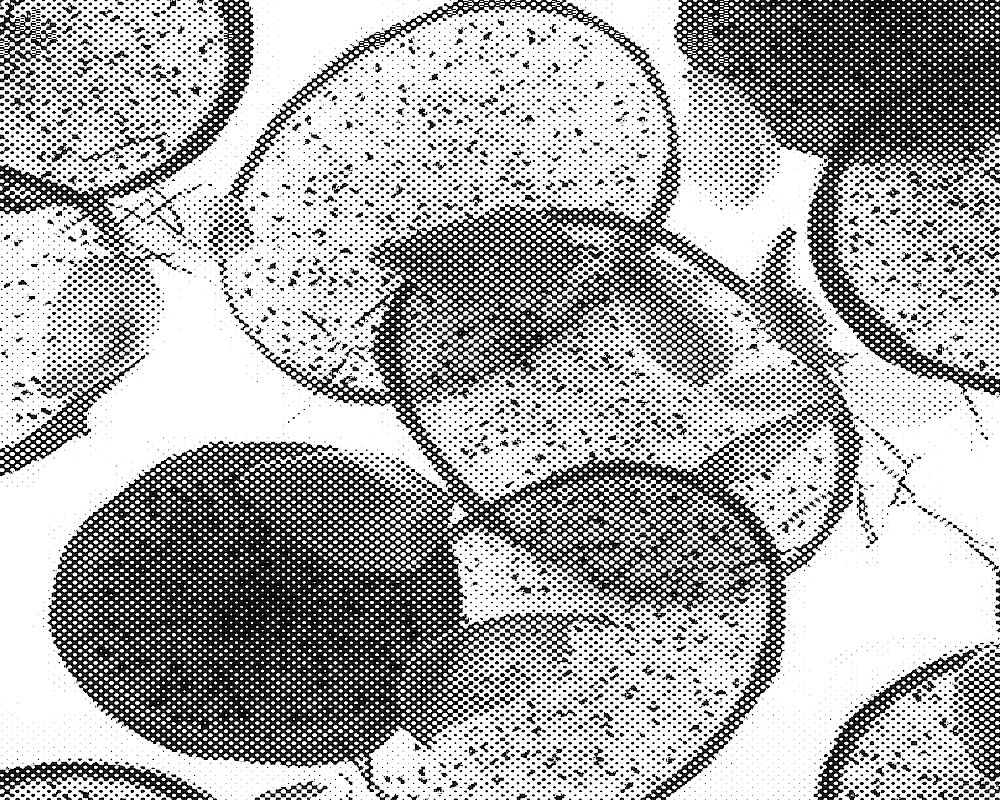

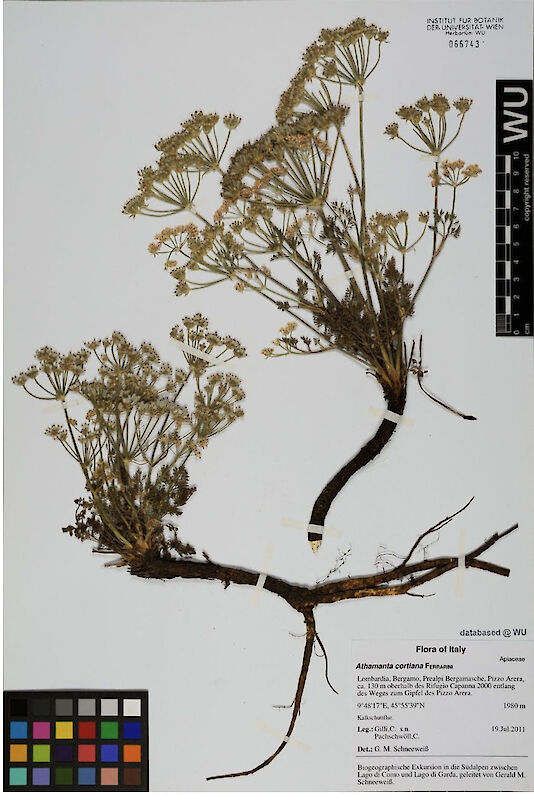

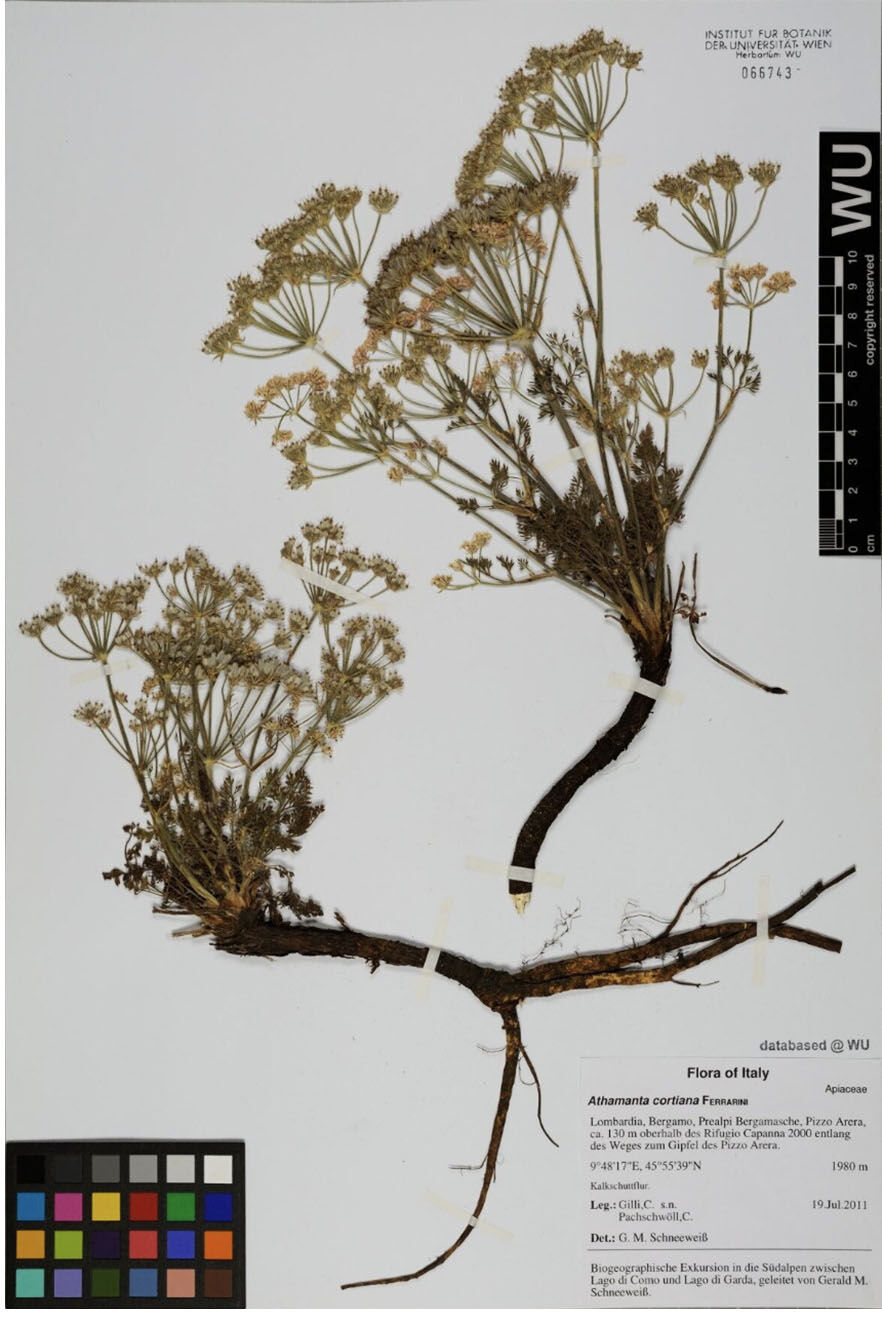

Athamanta cortiana Ferrarini is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the Apiaceae family. It features a woody stem covered with brownish scales and remnants of dead leaves. Its branches end in an umbel-shaped inflorescence, with lateral stems larger than the central one. The pinnate leaves have linear terminal segments, while the umbels consist of 15–20 densely hairy rays, bearing whitish-yellow flowers.

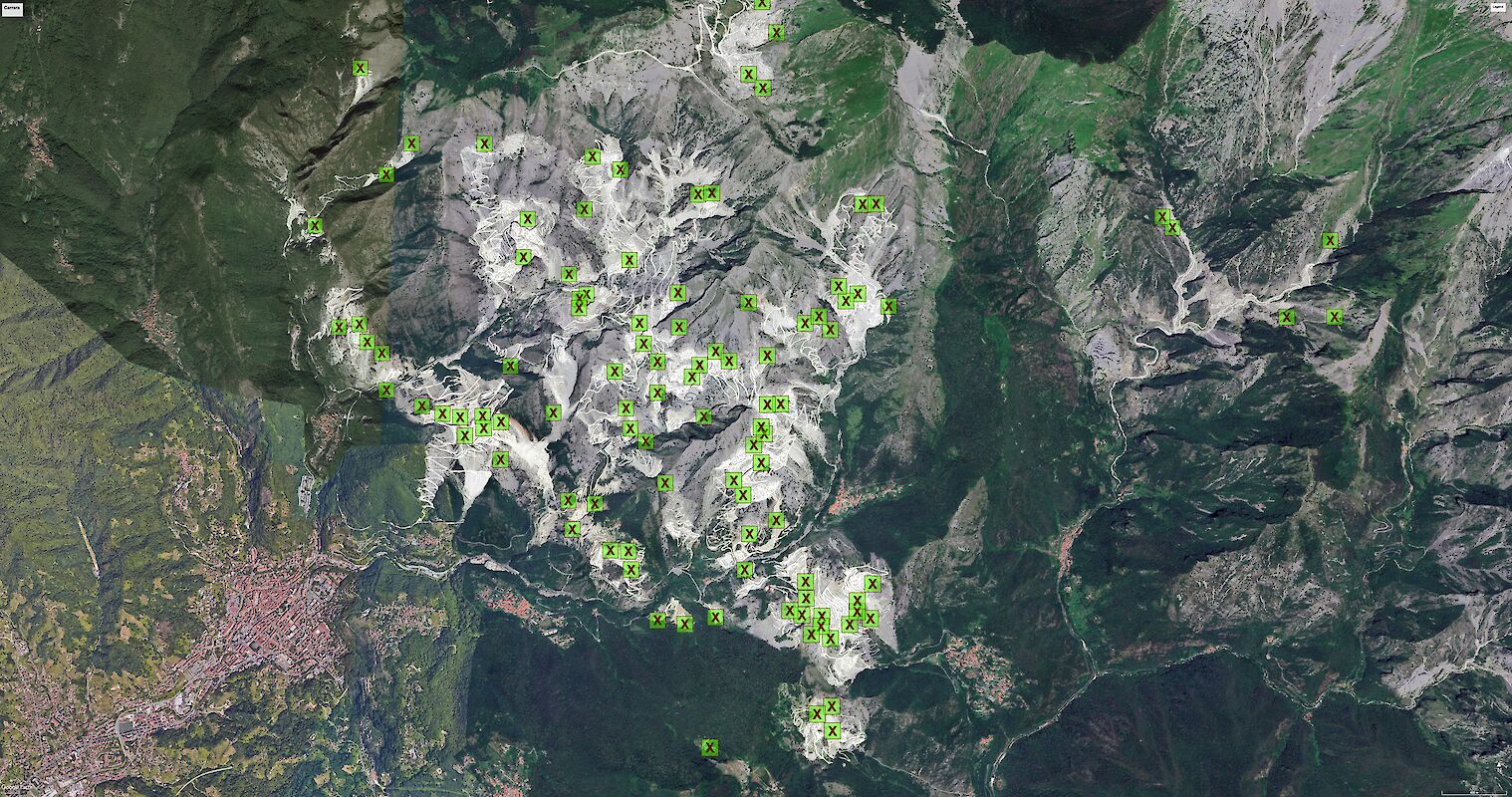

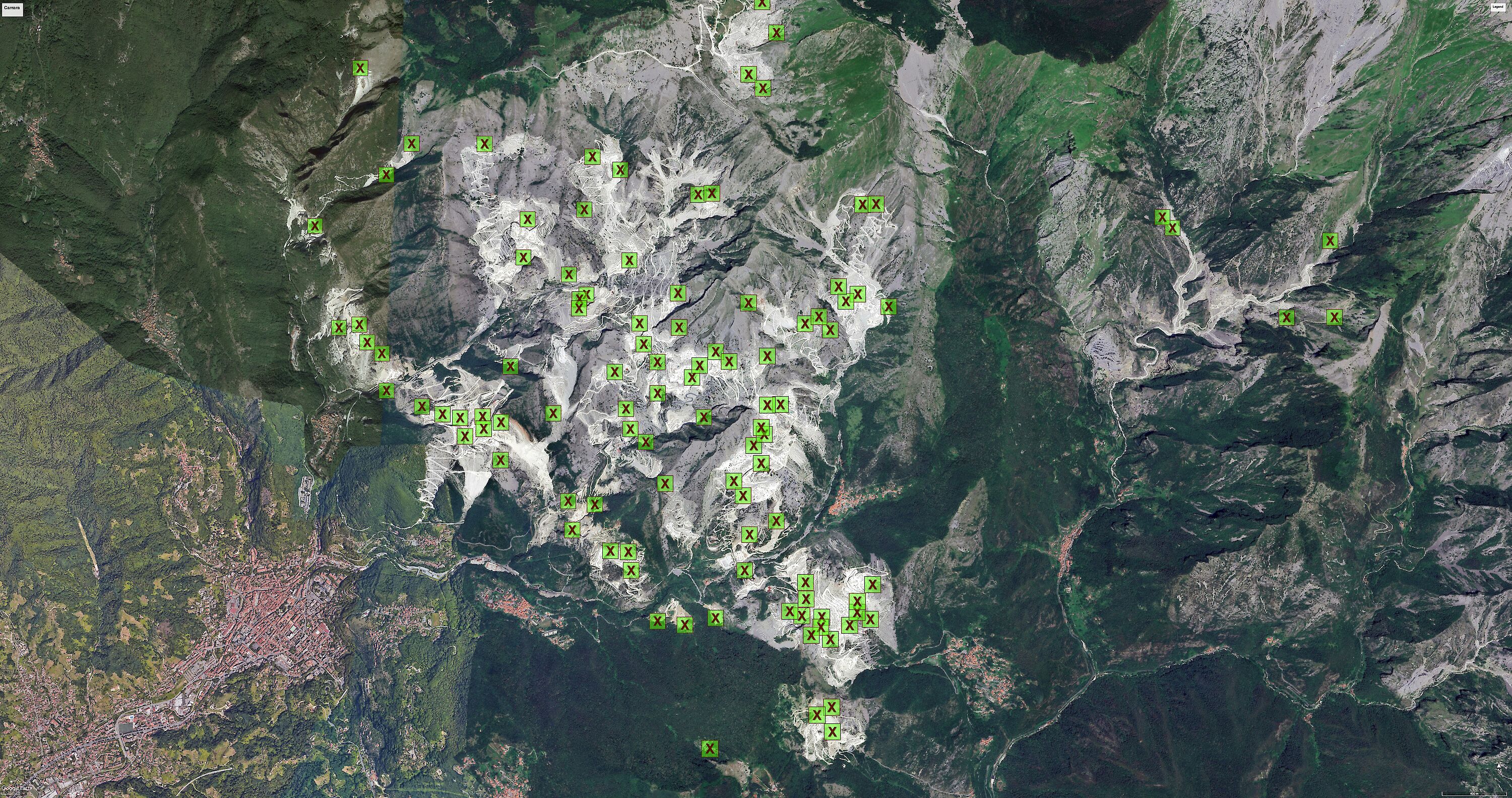

This ancient endemic species, currently at high risk of extinction, is found exclusively in the Apuan Alps, particularly on the highest peaks, such as Pizzo d’Uccello, Grondilice, Cresta di Garnerone, Contrario, Cavallo, Sella, Pizzo delle Saette, and Pania della Croce. However, 90% of the individuals are concentrated in two main populations: Pania della Croce (e.g., in Vallone dell’Inferno) and Passo delle Pecore (between Monte Contrario and Monte Grondilice).

Its habitat, confined to high-altitude rocky ridges, has been drastically reduced by the relentless expansion of quarries, leaving this unique species precariously close to extinction.

Flowering occurs between June and July, though it is extremely rare and does not happen every year. The species is critically endangered due to marble quarrying activities and the small size of its known populations.

In the last 30 years the Apuan Alps have been excavated more than in the last 2000 years. Carrara counts almost a hundred active marble quarries. The most recent report says that 3.3 millions tons of marble were mined in 2022. But where does it end up? General rules for the Italian stone industry set the wastage limit to 75% of the excavated material, with the exception of marble that can reach up to 95%. Since the 80s, the waste became very profitable and the parties involved have no interest in reducing or slowing the process down since instead of having to pay to dispose of it, they can actually sell it as it is. Nowadays, on average 80% of the quarried amount is rubbles and dust, or to better define it: calcium carbonate, a chemical compound highly used in food and pharmaceutical industries.

The quarries are part of the state property and the licensing to cultivate them is subjected to the Region’s authorisation. So the quarries’ owners only own the right to use them for extractive purposes. The quarries, as part of the Apuan Alps regional park, are a complex legal territory. On one hand the extractive activity makes them an economic asset; on the other hand, the geographical location makes them part of a landscape protected area.

The heavily industrialised method of extraction produces a lot of dust that, by law, should be disposed of in a controlled way but unfortunately is most of the times thrown along slopes or blown away into the air with high pressure washes, to save on disposal costs, which implicates destructive consequences on the surrounding environment and karstic system.

An extractivist system based on the privatisation of profits and the socialisation of costs that impact both communities and ecosystems that inhabit the territory. A diverse fallout: from threatening the 36 endemic species to severely polluting the water system.

Why do Carrara and its citizens identify with the commodity and not with the mountain?

Only the 0,5% of the extracted marble is used for artistic production and only 1% of Carrara’s population is working in the industry but the link between Carrara, its marble and the quarryman seems an everlasting association. The storytelling around is more mainstream than hegemonic but still, as seen before, it has irreversible impacts on the territory.

It’s a very strong contradiction, but similarly to other models of development, it ends up being seen as essential.

A collective of local activists, environmentalists, and residents who fight against the marble extraction in the region has taken the name Athamanta, taking a clear stand in shifting the narrative of the territory to a more tangible dimension by redirecting the gaze to its fragile natural beauty.

How did the Athamanta flower become a symbol of ecological resistance?

Athamanta cortiana Ferrarini and the more famous Edelweiss face a common threat: human activity. Yet, the ways in which they are endangered reveal two different forms of destruction. Edelweiss became a victim of its own symbolic power. Desired for its rarity and association with purity, courage, and the untouched wilderness, it was plucked from alpine cliffs by those who sought to possess a piece of that myth. Over-harvesting brought it to the edge, forcing the implementation of conservation laws to protect what was once abundant.

Athamanta cortiana, on the other hand, is not endangered because of human admiration, but because of human disregard. It is not the flower that is coveted, but the very land it grows on. The marble quarries carve away entire mountains, consuming the habitat where this delicate, lace-like plant clings to life. Unlike Edelweiss, which was taken too often, Athamanta resists in places that are being taken away, standing against an erasure not of itself, but of the ground beneath it.

This contrast reveals two faces of the same anthropic force: one that destroys through possession and one that destroys through appropriation of space. Edelweiss was nearly lost because humans wanted it too much; Athamanta cortiana risks disappearing because humans want everything but the flower.

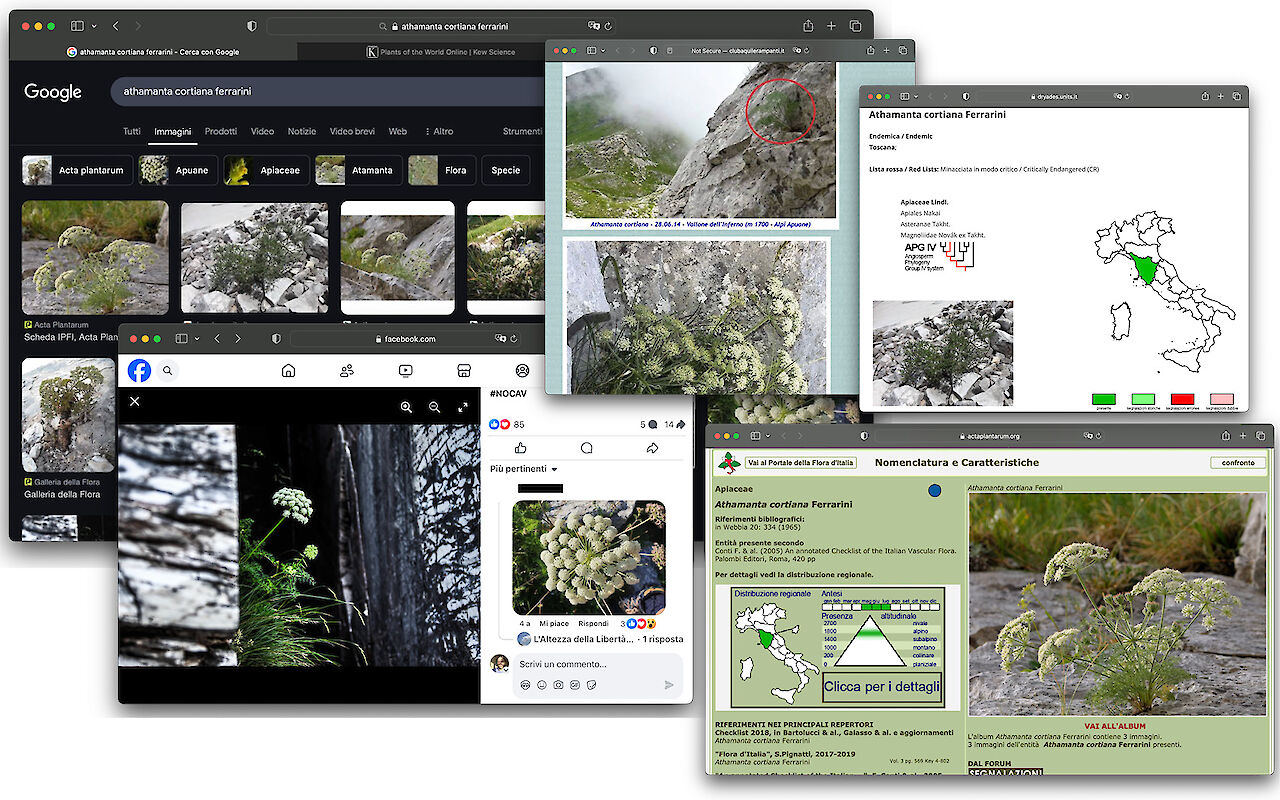

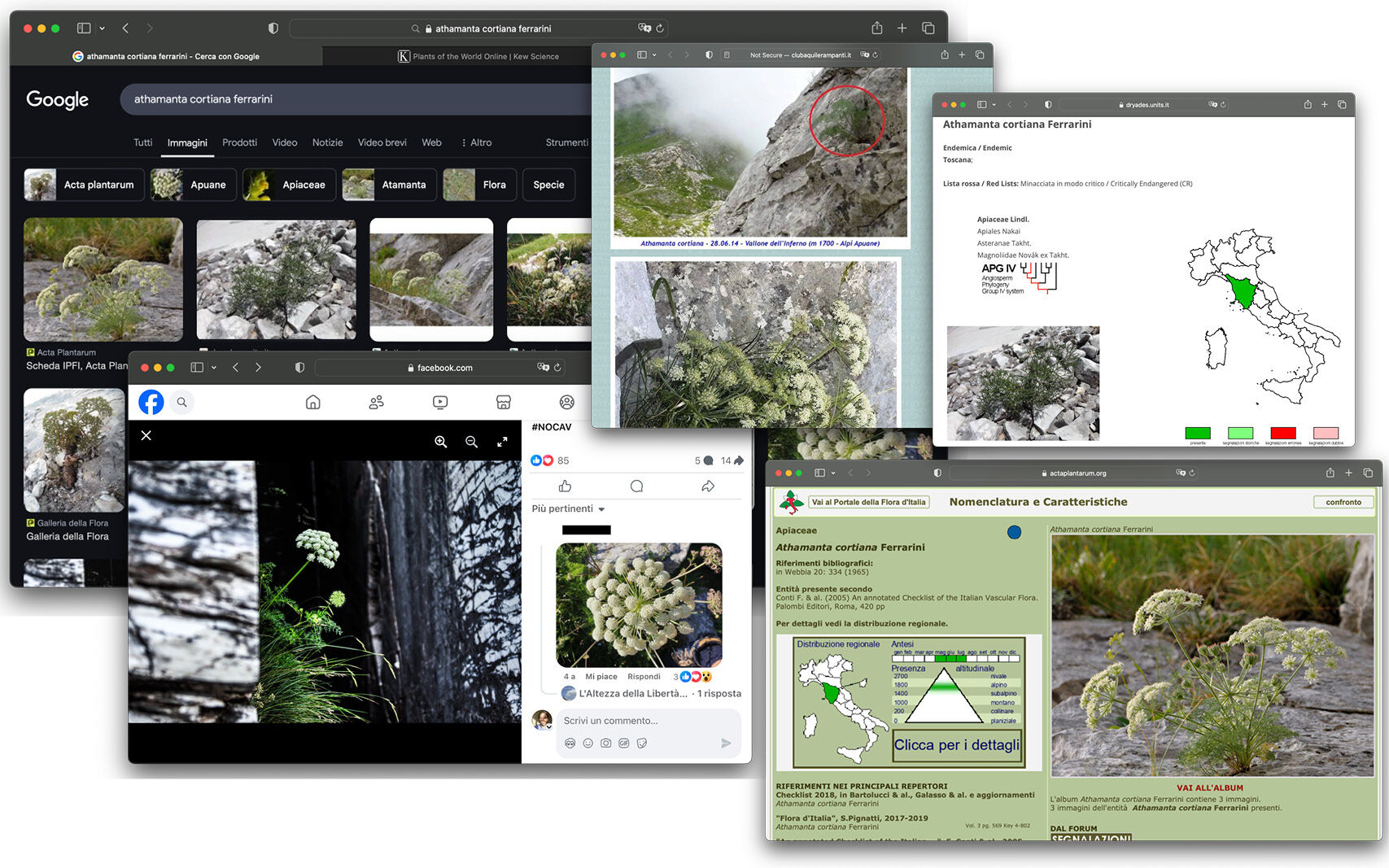

Even in how they are documented, this disregard is evident. While Edelweiss has been immortalised in countless photographs, symbols, and even romanticised in folklore, Athamanta cortiana remains largely unseen. There are very few images of it online, mostly taken by amateurs or botanists who happen to spot it — scattered, almost incidental records of its existence. This lack of visual presence mirrors its precarious status: a plant that is neither sought after nor protected, simply left to persist in the shadows of extraction. And yet, Athamanta continues to grow, surviving on mountains that have been hollowed out and broken. A testament not only to resistance but to nature’s quiet defiance in the face of disappearance.

Its lace-like flowers, white against the grey of marble quarries, tiny and fragile, grow where the land has been scarred by years of extraction. A visual declaration that life persists against the extractivist onslaught.

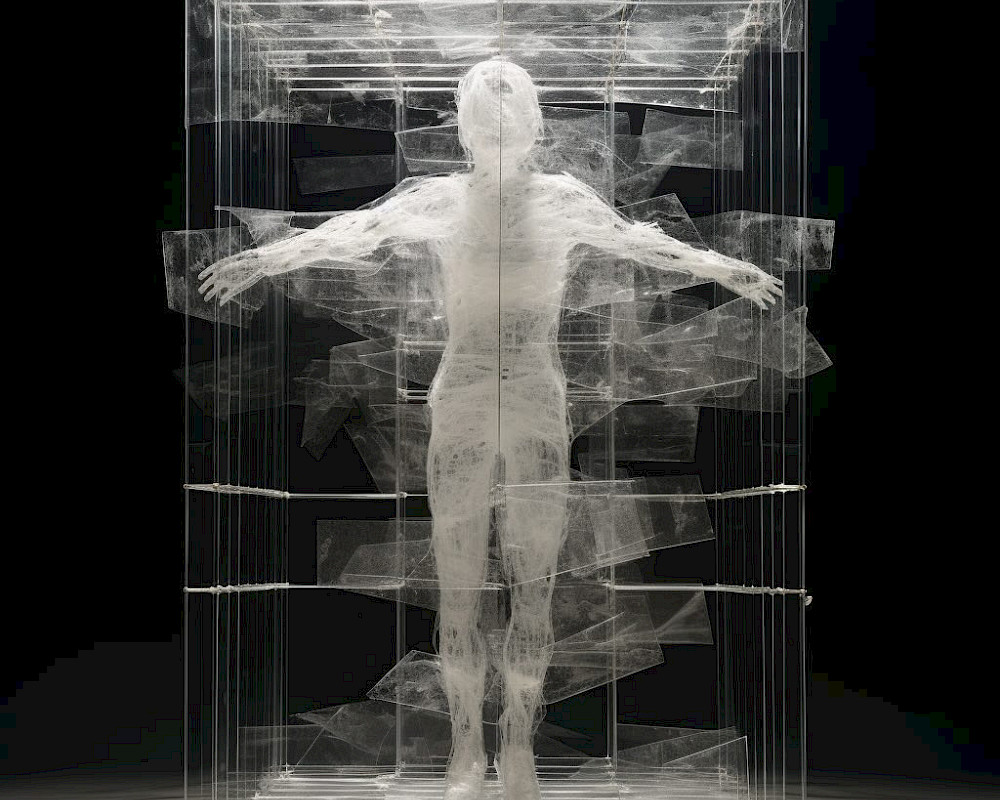

Its deep roots cling to the fractured rocks, anchoring themselves in what little remains of the mountain, drawing nutrients from something that seems barren and lifeless. Its ability to grow in these extreme conditions makes it a symbol of endurance, yet also highlights the precarity of species that thrive in disrupted landscapes.

Its endangerment is a direct result of human activity overpowering ecological balance, not just through extraction but also habitat fragmentation and climate shifts accelerated by industrialisation. If left undisturbed on less anthropized mountains, it might return to a state of natural rarity, no longer forced into the role of a survivor in a battlefield of stone and dust. But what would mean for it to "resist" without us? If we disappear, does resistance become mere existence?

The Athamanta flower would no longer be engaged in a fight against habitat loss or climate-induced challenges brought on by industrial activity. Instead, its survival would simply be a result of natural cycles and adaptive processes within its native habitat.

In this context, "resisting" could transform into “being”, a quiet persistence that blends into the larger ecosystem, no longer under the acute threat of extinction brought on by human activity. But I wonder if “resistance”- even without human influence - would truly disappear. The Athamanta, even in its natural environment, might still be “resisting” in its own way. It would still be striving for survival in the face of natural challenges: predators, competition with other alpine flora, and so on. But the twist is that this wouldn’t be resistance in the heroic sense we often romanticise when we talk about endangered species fighting for survival. It would be the kind of resistance that’s integrated, subtle, and ongoing, rather than something in opposition to a clear antagonist. And yet, without the human presence that forces it into a narrative of struggle, resistance might also be seen as irrelevant. In the absence of us framing it as a struggle, would the Athamanta flower simply become a part of the landscape once more? Wouldn’t its struggle for survival fade into the background of nature’s rhythms?

***

Bibliography

1. http://www.clubaquilerampanti.it/Atamanta%20di%20Corti.htm

2. https://dryades.units.it/floritaly/index.php?procedure=taxon_page&tipo=all&id=3523

3. https://athamanta.wordpress.com/chi-siamo/

4. https://www.actaplantarum.org/galleria_flora/galleria1.php?id=2564

5. https://www.ildolomiti.it/altra-montagna/ambiente/2024/lestrattivismo-nelle-alpi-apuane-chiara-bruacher-del-collettivo-athamanta-per-il-podcast-un-quarto-dora-per-acclimatarsi

6. https://www.ice.it/it/sites/default/files/inline-files/Nota%20di%20Mercato%20- %20Lapideo%202023.pdf

7. https://tno.camcom.it/sites/default/files/sala_stampa/2024-12/20241206-Presentazione-Osservatorio-marmo.pdf

8. https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/672962/feart-09-672962-HTML/image_m/feart-09-672962- g001.jpg

9. http://www.parcapuane.it/vetrina/vetrina_geologia.asp

***

This piece is a contribution to the digital zine “Imaginary Gardens”, conceptualized and produced by the 1st-year Contextual Design masters students at Design Academy Eindhoven, May 2025