video

Passiflora (My New Roommate)

Mia Domenech Puras

Mia Domenech Puras is an multimedia artist born in Puerto Rico and currently based between Eindhoven and Paris.

5

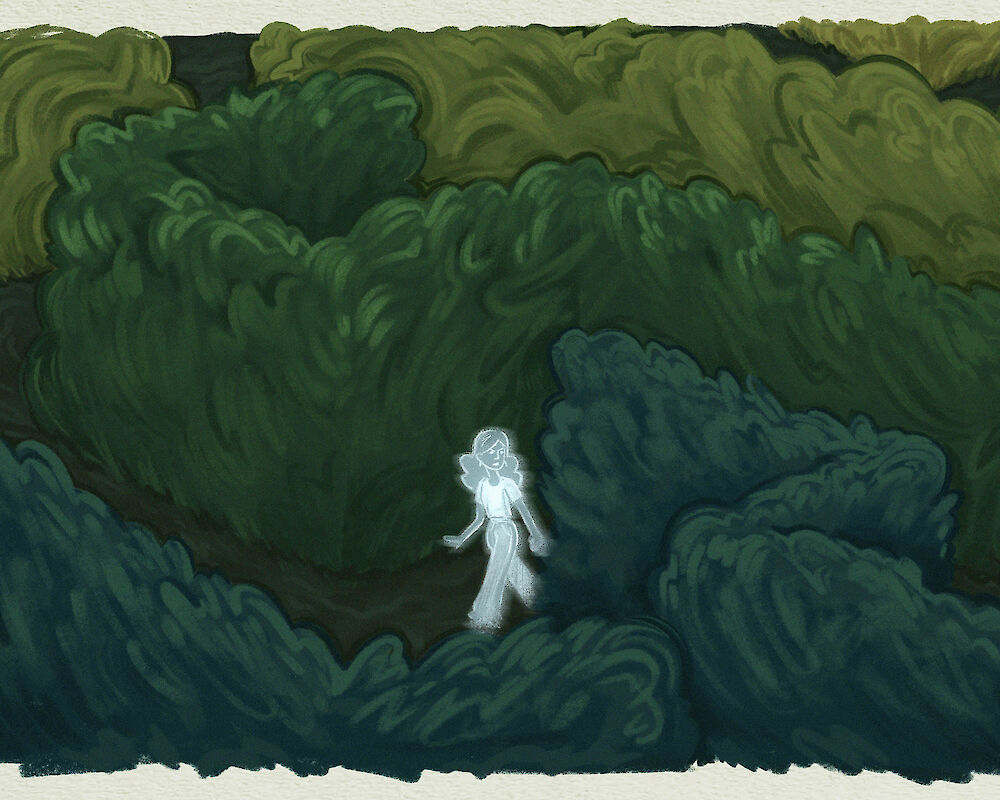

min readWhen I moved to Eindhoven, everything felt foreign—until I saw a wall of passion flowers at my new home. It brought me comfort and a sense of belonging.

I began noticing this flower throughout the Dutch landscape, which led me to question: Where did it come from? Why was it here? I discovered that there are over 550 species of passion flowers, with 20 found in Puerto Rico. Yet the one growing in my backyard and scattered across the Netherlands—the Passiflora caerulea, or Blue Passion Flower—is absent from my island.

Native to South America, Passiflora caerulea was named by Spanish missionaries, who linked its floral structure to Christ’s Passion: its ten petals representing the apostles, the filaments symbolizing the crown of thorns, the anthers the five wounds, and the three stigmas the three nails.

Colonizers weaponized this symbolism, using it to indoctrinate Indigenous peoples across Latin America and the Caribbean.

This flower is known for its ability to ease anxiety and insomnia when brewed into tea or extracted naturally. Ironically, the species growing in my yard can be fatal when consumed. It spreads invasively from my neighbor’s garden, entangling everything— this invasive nature is symbolic of historical forces disrupting local ecosystems and cultures.

This sparked my interest in reimagining myself as a botanist. I began researching Dr. Agustín Stahl, Puerto Rico’s first botanist. In the 19th century, his work was transformative. As both a scientist and an advocate for the island’s autonomy, Stahl intertwined Puerto Rico’s natural history with its national identity. Unlike European botanists who withheld their findings from locals, Stahl gave Puerto Rico its own botanical studies.

Born in Curaçao to a German father and Dutch mother, he moved to Puerto Rico as an infant under Spanish colonial policies. Educated in Germany, he became a distinguished doctor and later dedicated his life to the study of botany, zoology, archaeology, and indigenous cultures, collaborating with renowned international scientists. Stahl amassed extensive natural history collections with the goal of establishing a museum of natural history on the island (One that we did not have and still don't). In 1874 he was appointed Professor of Natural History at the Provincial Institute of Puerto Rico. This appointment was short-lived as the Governor José Laureano Sanz closed the Institute in the same year (typical). Dr. Stahl defended the liberties of his country when it was under the oppressive Spanish regime. Stahl was imprisoned on several occasions due to his liberal ideas and challenging perspectives on Spanish domination.

On May 4, 1898, Dr. Stahl was traveling on a boat from San Juan to Cataño, on his way home to Bayamón. In the capital, the Spanish supporters were celebrating the death of General Antonio Maceo, which occurred during the Cuban war. Cuba struggled at the time for its independence. In the boat, a follower of the unconditional party sat close to Dr. Stahl and asked him:

“Dr. Stahl, What do you think of Maceo’s death?

-You guys are always the same, intransigents!

What? You do not approve of the party that has been organized in San Juan?

- The death of a brave contender is never rejoiced. The enemy in life is fought, and in death, if merited, is honored. (Carreras, 1957)”

Ten days after this incident, Stahl was exiled to the Dominican Republic. His banishment was short-lived as he was able to return to Puerto Rico in July 1898, just after the Americans defeated the Spanish government in Puerto Rico

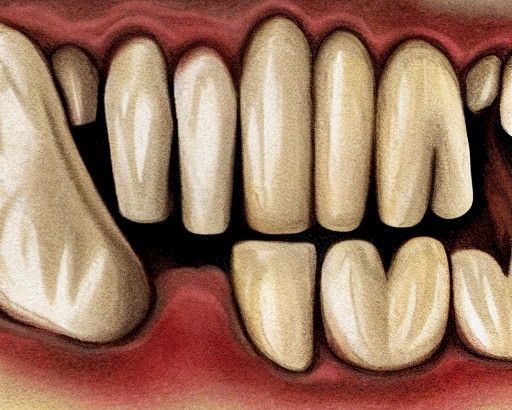

Stahl gave his entire practice and life to his love for Puerto Rico. He gave the island it’s own botanical narrative. He made a series of a total of 137 watercolors of PuertoRican Flora. In which 13 are passion flowers. As I was studying this flower: painting, dissecting, observing I was also questioning my relationship with Stahl and therefore my relationship with my identity.

By late October, only one flower remained in my backyard before they all disappeared for the winter. I deepened my relationship with it—observing, speaking to it, photographing, and recording it.

Through the passionflower, I traced unexpected connections—between places, histories, and identities. What began as a personal curiosity unraveled into a broader meditation on belonging, displacement, and the ways knowledge is claimed and passed down. Just as Stahl sought to give Puerto Rico its own botanical narrative, I found myself questioning the narratives I have inherited. The flower in my yard, thriving where it does not belong, serves as both a reminder and a question: How do we reconcile beauty with the histories it carries? In studying it, I was not only looking at a plant but at the quiet persistence of history—entangled, invasive, and still unfolding. The more I observed, the more I understood that even the most serene and beautiful spaces, like gardens, can conceal layers of colonial violence. What seems natural is often the result of imposed histories, shaping not only our landscapes but also our understanding of ourselves.

***

This piece is a contribution to the digital zine “Imaginary Gardens”, produced by the 1st-year Contextual Design masters students at Design Academy Eindhoven, May 2025